Anatomy of Biopharma Royalty Deals

Biopharma royalty deals are financial transactions where an investor purchases the right to receive future royalty payments from a drug or therapy, in exchange for an upfront payment (and sometimes milestone payments) to the selling party. These arrangements have become an important alternative financing mechanism in the pharmaceutical and biotech industry, especially in the past few years when traditional equity markets have been challenging.

Unlike standard loans or equity investments, royalty financings are non-dilutive (they don’t require giving up stock ownership) and the payments to investors come only from product revenues (if the drug succeeds). This means the investor’s returns are directly linked to the drug’s performance – aligning incentives with the product’s success, much like an equity stake, but without taking actual equity control.

Academic institutions were early adopters (often selling royalties from licensed discoveries), and now biotechs and pharma companies increasingly use royalty deals to fund R&D, clinical trials, or product launches without issuing new stock.

Key Types of Royalty Transactions

Royalty deals can be broadly categorized into two types

(1) Traditional royalty monetizations – the sale of an existing royalty interest (usually on an approved, revenue-generating drug), and (2) Synthetic or development-stage royalties – financing arrangements that create a royalty interest in a product that is in development or recently launched (often structured in between a sale and a loan). While both involve exchanging future revenue streams for upfront cash, the structure and risk profile differ significantly.

Traditional Royalty Monetizations (Commercial-Stage Deals)

In a traditional royalty monetization, the seller already has a right to royalties or revenue from a product. Commonly, this is a licensor of a drug (like a small biotech or university that licensed a patent to a pharma company in return for royalties on sales). The seller “monetizes” this by selling some or all of those royalty rights to an investor.

The investor pays an upfront lump sum and in return receives a contractually specified percentage of the drug’s future sales (the royalty stream). These deals usually occur when a drug is at or near commercialization – often already FDA-approved or very close (e.g. after filing for approval). Because the product’s prospects are more certain, these transactions carry less risk for the investor than pipeline deals.

Typical Structure

The investor’s royalty share can range from a small slice of sales to the entire royalty that was owed to the seller. In surveyed deals from 2020–2024, traditional monetizations involved royalty rates roughly between ~17% up to 100% of the underlying sales royalty right. (100% implies the buyer purchased the entire royalty interest, whereas lower percentages mean a partial sale.)

The investor generally continues to collect royalties until the drug’s patent/exclusivity expires or until a specified contract term. Many such deals do not impose caps on the total payout – the investor takes on the risk of underperformance but also keeps the upside if sales boom. In fact, about 72% of traditional royalty deals had no payment cap at all. If a cap is used (say the investor will stop collecting once they’ve received 2x their investment), typically the agreement specifies what happens afterward. Often, after a cap is hit, the royalty stream reverts fully to the seller (no “tail”).

In some cases a small tail royalty may continue even after the cap, allowing the investor to keep, for example, a low single-digit royalty beyond the cap. However, this is less common (only ~18% of capped traditional deals included a tail).

Risk Profile and Terms

Because these deals involve approved, revenue-generating products, they are viewed as lower risk. The investor’s main risks are commercial – will sales meet expectations? – rather than binary technical risks of drug failure. Thus, investors accept a lower required return here than for pipeline assets. Traditional royalty streams are often valued with discount rates in the high single-digit to low-teens percent range, commensurate with the stable, lower-risk cash flows.

Structurally, these deals are frequently done as a “true sale” of the asset: the royalty rights are typically transferred to the investor’s special-purpose vehicle outright. This means the seller removes that royalty asset from their balance sheet in exchange for cash, and the investor cannot claim other assets of the seller – their recourse is only to the royalty stream itself.

Indeed, the vast majority (~94%) of traditional royalty financings are true sales rather than debt (gibsondunn.com). As a result, no collateral or liens on company assets are usually involved in pure monetizations (about 89% had no product asset liens).

The seller gets non-dilutive financing and offloads some risk, and the buyer gets a steady revenue-based return. These deals have become quite sizable; for instance, in 2023 PTC Therapeutics sold a portion of its royalty on the spinal muscular atrophy drug Evrysdi for $1.5 billion upfront (wilmerhale.com), illustrating how a single product’s royalty can be leveraged for significant capital.

Synthetic Royalty & Development Financing Deals (Pipeline-Stage)

“Synthetic” royalty deals refer to cases where a royalty interest is created or promised on future sales of a product, rather than an existing third-party royalty being sold. These often occur when a company with a pipeline drug (Phase 1, 2, or 3) needs funding for development or launch. An investor provides cash in return for a contractual right to a percentage of future sales of that drug (if and when it comes to market).

Since the drug may not yet be approved (or even past early trials), these deals carry higher risk and thus have more complex structures to manage that risk.

Typical Structure

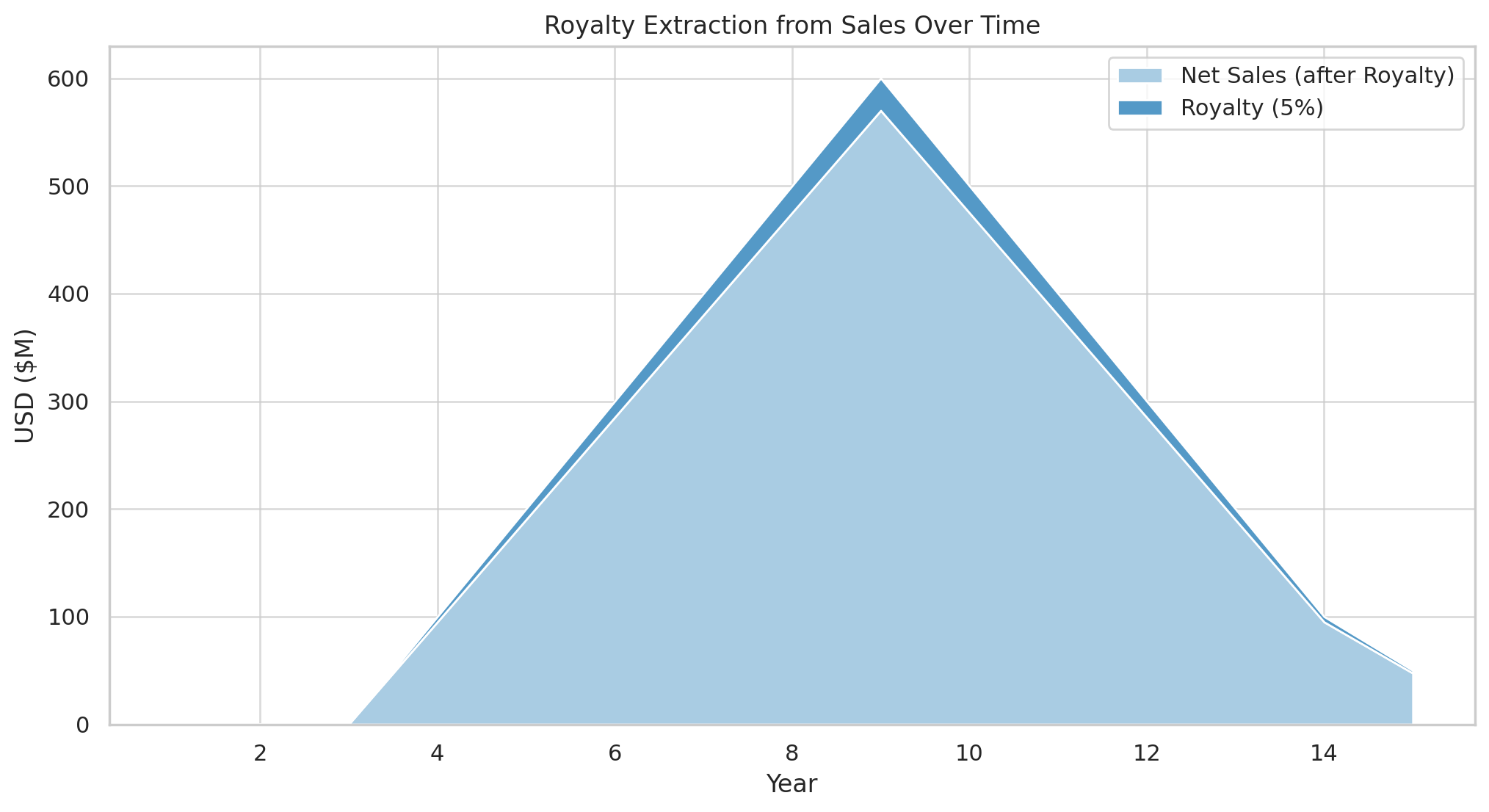

The investor usually pays an upfront sum and may also commit to future funding tranches or milestone payments – for example, additional funding upon positive Phase 3 results or upon FDA approval. In exchange, the investor will receive a royalty on the product’s future net sales (often a single-digit percentage). Because the company itself will be selling the product (there isn’t an external license paying royalties), this is a “synthetic” royalty defined by the contract. Royalty rates in synthetic deals tend to be relatively small slices of sales – a recent survey found rates ranging roughly from 0.75% up to ~14% of net sales in these deals (gibsondunn.com).

The percentage is lower than traditional deals because it’s an add-on to the company’s own revenue stream (the company typically retains the majority of revenue after paying the royalty). Synthetic royalty contracts often include performance thresholds and caps. It’s common to cap the total return for the investor – a median cap is around 2.0x the investment (though it can vary case by case).

For example, an investor might receive royalties until they have gotten two times their principal back, or until a certain year, whichever comes first. If there is a cap, usually once it’s reached the royalty obligation ends (no further payments) – indeed most deals with caps do not have an extended tail beyond the cap.

This feature protects the company from giving away an unbounded upside if the drug becomes a mega-blockbuster. On the flip side, if the drug performs poorly or fails, the investor could end up losing money (there is typically no guarantee of principal repayment in true sale structures).

Debt-Like Features

Many development-stage royalty financings include debt-like provisions to manage risk. Often these deals are structured “somewhere between” a sale and a loan. For example, the agreement might stipulate that if the product fails to reach certain sales or approval milestones by set dates, the company must make “make-whole” or gross-up payments to the investor to ensure a minimum return.

In other words, the company might guarantee the investor a certain IRR or allow the investor to accelerate payments due if milestones are missed. There is usually a lien on the product’s IP and assets in these deals (e.g. on the drug patents, regulatory approvals, etc.), similar to collateral in a loan. In fact, about 86% of synthetic deals include product asset liens (versus only ~11% of traditional deals)g.

The investor may also impose restrictive covenants on the company’s actions regarding that asset (or sometimes overall), to protect their interest. Because of these features, a large portion of pipeline royalty financings are structured as debt or debt-like instruments rather than pure sales. (In the 2020–24 survey, only ~35% of synthetic deals were true sales; the majority were effectively loans or carried debt-like covenants).

Risk and Timing

Investors in development royalties are taking on substantial clinical and regulatory risk – if the drug fails in trials or is not approved, the expected royalty stream never materializes. Therefore, these deals tend to happen for assets that are somewhat de-risked, often around Phase 3. In fact, industry experts note that availability of royalty financing “opens up around the time of a positive Phase 3 data readout” for a product (wilmerhale.com).

Deals at Phase 1 or 2 are rarer, but they do occur when the asset is especially promising or in an in-demand field. In such cases, the terms for the investor are correspondingly more favorable to compensate the high risk (for instance, the royalty percentage or the cap multiple might be higher). An example of a development-stage royalty deal is the 2020 agreement between Blackstone Life Sciences and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals: Blackstone paid $1 billion upfront for a 50% share of Alnylam’s royalties on inclisiran (a then Phase 3 cholesterol-lowering drug), also committing up to $1 billion in R&D funding for Alnylam’s pipeline (zs.com).

This large deal was structured so that Blackstone assumed significant risk on inclisiran’s approval and commercial performance in exchange for a substantial royalty stake. Generally, because these transactions sit in a gray area between an outright sale and a secured loan, they require careful negotiation to balance risk-sharing. Companies must pay attention to how covenants and liens might limit their flexibility (for example, an investor might restrict the company’s ability to incur additional debt or to partner the drug with another company without consent).

In short, synthetic royalty financings give companies a way to fund development without diluting equity or out-licensing, but at the cost of pledging a piece of future success and accepting strings attached.

Major Players and Market Trends (2019–2025)

Over the last 3–5 years, the market for biopharma royalty deals has grown significantly, fueled by investors seeking steady returns and companies seeking cash in a difficult funding environment. Annual deal volume has been estimated around $14 billion per year in recent years. Notably, royalty financings have been growing at an estimated ~45% compound annual growth rate – much faster than traditional equity or venture funding in biotech.

Even during the 2022 downturn in biotech (when IPOs and stock prices collapsed), royalty financings held steady or grew, indicating their resilience to macroeconomic swings. This surge is driven by the appeal of non-dilutive capital for companies and relatively predictable, uncorrelated returns for investors.

Key Investors

A few specialized firms have dominated this space. Royalty Pharma is the largest player – over the past decade it accounted for ~36% of all royalty origination deal value (about $4.2 billion)zs.com. Royalty Pharma, founded in 1996, went public in 2020 and has a diverse portfolio of drug royalties. Next is HealthCare Royalty (HCR) Partners (~19% of deal value) and Blackstone Life Sciences (~16%).

Together, these three made up ~71% of the biopharma royalty investment volume in the past ten years. Other notable investors include DRI Capital, OMERS Capital (a Canadian pension fund active in royalties), Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), Oberland Capital, XOMA, and RTW Investments, among others.

In 2021–2022, new entrants (including large institutional investors and private equity firms) started to participate more, contributing to almost half of the market value in 2021 dealszs.com. This indicates growing acceptance of royalties as an asset class. Some pharma companies themselves have units that do royalty deals, and occasionally pension or sovereign wealth funds directly invest in royalty streams for long-term yields.

Typical Deal Structures and Terms

Despite the bespoke nature of each transaction, royalty deals tend to include a common set of structuring elements and terms. Understanding the anatomy of these deals means examining how cash flows, contingencies, and protections are built into the agreement.

Upfront Payment and Milestones

Almost every royalty deal provides an upfront lump-sum payment to the seller at closing. This is the primary consideration for selling the future royalties. In some deals, especially for pipeline assets, the total payment is split: a portion is upfront and additional amounts are tied to milestones (e.g. FDA approval, first commercial sale, certain sales thresholds).

These milestone payments allow the investor to commit more capital only if the asset hits key value-inflection points, thereby mitigating risk. For example, a deal might pay $50 million upfront and $50 million more upon Phase 3 success. Milestone-heavy structures have grown more popular recently, as they lower the investor’s downside risk and also lower the seller’s effective cost of capital (since the seller only gets the second tranche if the product advances).

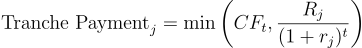

Royalty Percentage and Tiers

The core economic term is the royalty rate – the percentage of product sales that will be paid to the investor. In traditional deals, this often corresponds to an existing license royalty (for instance, a university might be entitled to 5% of sales under a license – selling 100% of that royalty gives the buyer 5% of sales). In synthetic deals, the royalty can be negotiated from scratch. Rates can be flat or tiered. A flat royalty means the same percentage applies to all sales. Tiered royalties are also common: the percentage might step up or down at certain sales levels or time periods.

For example, an investor might get 12% of sales up to $1 billion annual revenue and 15% on the portion above $1 billion. Tiers can also be used to ensure a minimum return – some contracts have provisions like “if cumulative royalties by year X haven’t reached $Y, the rate increases by a few points thereafter” to help the investor catch up.

Survey data indicate that flat royalties were slightly more common than tiered in recent deals (about 72% of traditional and 73% of synthetic financings used a flat structure, with the rest tiered). The specific rate is influenced by the drug’s sales projections and risk: a high anticipated sales volume might allow a lower rate (so the investor’s absolute return still meets their target), whereas a riskier or smaller asset might warrant a higher rate or a bigger portion to the investor.

Caps on Payout

As mentioned, many deals – especially synthetic – include a cap on the total payments to the investor. This is essentially a built-in end point: once the investor has received a certain multiple of their investment, their right to royalties can end (or switch to a lower tail rate). Caps typically range from 1.5× to 4× the initial investment, depending on how risky the asset is and negotiating leverage (wilmerhale.com).

A lower cap (closer to 1.5–2×) is more favorable to the company (the investor’s upside is limited), but it usually comes with a lower royalty rate or is seen in deals where the risk is low (almost like quasi-debt). Higher caps (3–4×) appear in riskier deals to compensate investors for the chance the drug fails. It’s worth noting that traditional monetizations of very proven assets often skip caps altogether, since sellers of a valuable royalty prefer not to cut off the upside.

For instance, when UCLA sold its royalty interest in the cancer drug Xtandi for $1.14 billion, reports did not indicate any cap – UCLA simply gave up its stream in perpetuity (zs.com). On the other hand, in a development financing, a cap is a sensible compromise: the company shares future profits but if the drug wildly exceeds expectations, the company can regain the full benefit after the investor achieves a healthy return. As noted above, if a cap is in place, typically no further “tail” payments go to the investor after hitting the cap (most deals are no-tail after cap by design).

Term and Termination

The duration of royalty rights is usually tied to the life of the product’s patent or exclusivity. In a pure royalty sale, the investor might receive royalties “for the Duration of the Licensed Patents” or “until Market Exclusivity expires” on the drug, which effectively means until generic competition is allowed. Some deals instead fix a term of years, but that is more common in loan-like structures. If a cap is reached before patent expiry, that triggers early termination of payments.

Additionally, contracts often have buyout or buy-back options – for example, the company might negotiate the right to buy back the royalty after X years for a predefined price (this is a call option), or the investor might have the right to force a buyout under certain conditions (a put option). Such clauses add flexibility: a company might regain its full revenue stream later, or an investor can secure an exit. Bespoke terms like these have become more common as the market matured.

Security and Control Provisions

A critical structural aspect is whether the deal is treated as a sale or a secured financing. In true sales, the investor’s only recourse is to the royalty stream itself. In secured loan-style deals, the investor (lender) will take a lien on the product assets. This means if the company defaults on obligations (like gross-up payments or if it sells the asset), the investor can claim the drug’s intellectual property or related assets as collateral. Along with liens come covenants – the company may be restricted from incurring new debt secured by the same assets, may have to maintain certain financial ratios, or may be limited from selling or licensing the asset elsewhere without consent.

For example, a development royalty deal might prohibit the biotech from out-licensing the drug to another pharma unless the royalty investor agrees, ensuring the investor’s interests aren’t undermined.

Data shows that nearly all synthetic/development deals impose such negative covenants (96% had them) whereas most traditional monetizations did not require covenants (only ~33% had any, usually light ones).

This contrast stems from the fact that in a traditional sale, the seller is often just an IP holder with no further performance obligations, so the investor doesn’t need to police the company’s behavior much. In a development deal, the company is still developing and marketing the product, so the investor wants to ensure they don’t jeopardize the asset or take actions that subordinate the investor’s claim.

True Sale vs. Accounting Treatment

The theoretical underpinning of royalty monetizations is that by structuring as a true sale, companies can treat the influx of cash as a one-time revenue and remove future royalty obligations from their books (off-balance-sheet financing), rather than booking it as debt. This can be advantageous for accounting and for avoiding debt covenants. However, to qualify as a true sale (and not have to count it as a liability), the deal must be carefully structured legally. Often a separate special-purpose vehicle (SPV) is created by the investor to purchase the royalty, and funds flow through that SPV.

If a deal is instead structured as a loan (even if repayments are made from royalties), it will appear as debt on the company’s balance sheet. Some companies prefer one or the other depending on their priorities. It’s common to see law firms and accountants analyze a deal’s features to determine if it meets the criteria of a sale. For example, absence of a guaranteed principal payback, transfer of significant risks to the buyer, and no obligation for the seller to compensate if royalties are insufficient are hallmarks of a true sale.

Examples of Terms

As an illustration, consider a hypothetical royalty financing for a Phase 3 oncology drug: An investor pays $100 million now, and will fund another $50 million upon FDA approval. In return, the company grants a royalty of 8% of net sales of the drug. The royalty will end once the investor has received $300 million (a 3× cap) or 12 years post-launch, whichever comes first.

If the drug fails approval, the company owes nothing further (investor loses out), but if the drug is delayed in approval beyond a certain date, the company agrees to pay a one-time $20 million fee (a form of risk sharing). The investor takes a lien on the drug’s patents, and the company agrees not to out-license the drug or use it as collateral for other loans. This setup balances risk: the investor could make 3× if the drug is a hit, but if the drug fails, the investor could also lose a large portion of their investment (with only the patents as collateral).

Valuation of Royalty Deals: Theory and Models

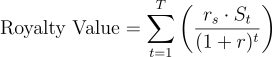

Valuing a royalty stream is fundamentally an exercise in discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, but with important twists to account for risk. The key idea is that the value of a royalty is the present value of all the future royalty payments the investor expects to receive. In a simple scenario (an approved drug with reasonably predictable sales), one would project the drug’s sales each year, multiply by the royalty percentage, and then discount those cash flows to present using an appropriate discount rate. The formula for the present value (PV) of a royalty stream can be represented as:

where r$ is the discount rate (reflecting the investor’s required rate of return and time value of money), and t is the time period over which royalties are received (typically up to patent expiration). This is essentially the same as valuing a bond or any cash-flow-producing asset.

Choosing the Discount Rate

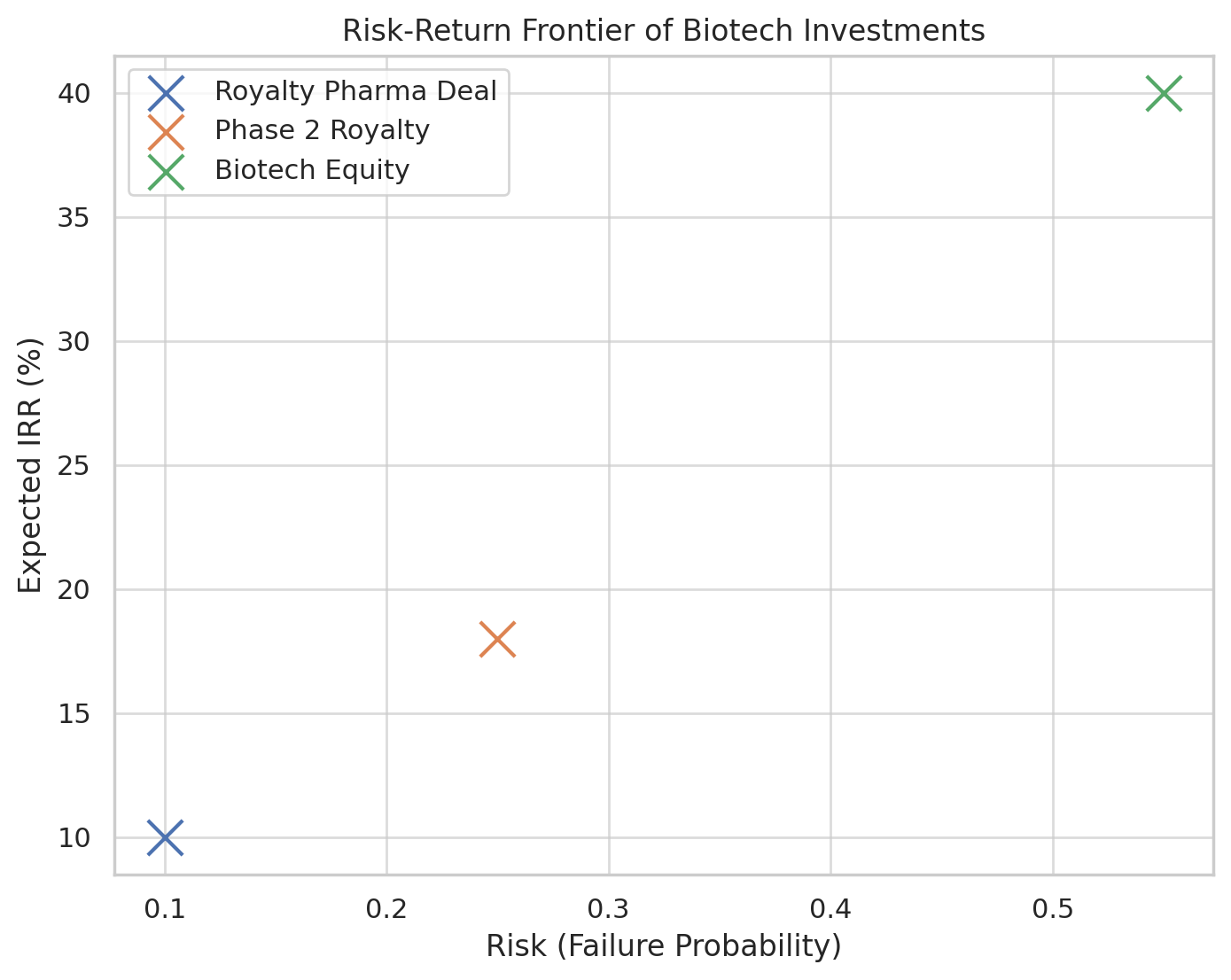

In practice, the discount rate used is critical and depends on the riskiness of the royalty stream. Royalty investors require higher returns for riskier assets (those that might not generate the cash flows at all). For an approved, in-market drug, the risks are mostly commercial (market adoption, competition) and maybe some regulatory (e.g., pricing pressures).

Such cash flows might be discounted at rates in the high single digits or low teens, as noted earlier. For example, one study found late-stage or marketed biotech projects often used discount rates around 15–20% or lower, and even as low as ~10% for very secure, market-stage assets. However, for a drug still in clinical trials, there is a significant probability of failure. Investors can account for this in two main ways:

High Discount Rate (VC method)

One approach (often used by venture capital investors) is to fold all risks into an elevated discount rate. For instance, an early-stage drug might be discounted at 30–40% (or even higher) to reflect the compounded probability that it might never reach market.

Indeed, a survey of biotech valuation experts found average discount rates of about 40% for early-stage projects, ~27% for mid-stage, and ~19% for late-stage. These high rates attempt to cover the risk of failure by demanding a very high potential return on the money if the drug succeeds. Essentially, the fewer the guarantees, the bigger the “risk premium” baked into.

Risk-Adjusted NPV (rNPV)

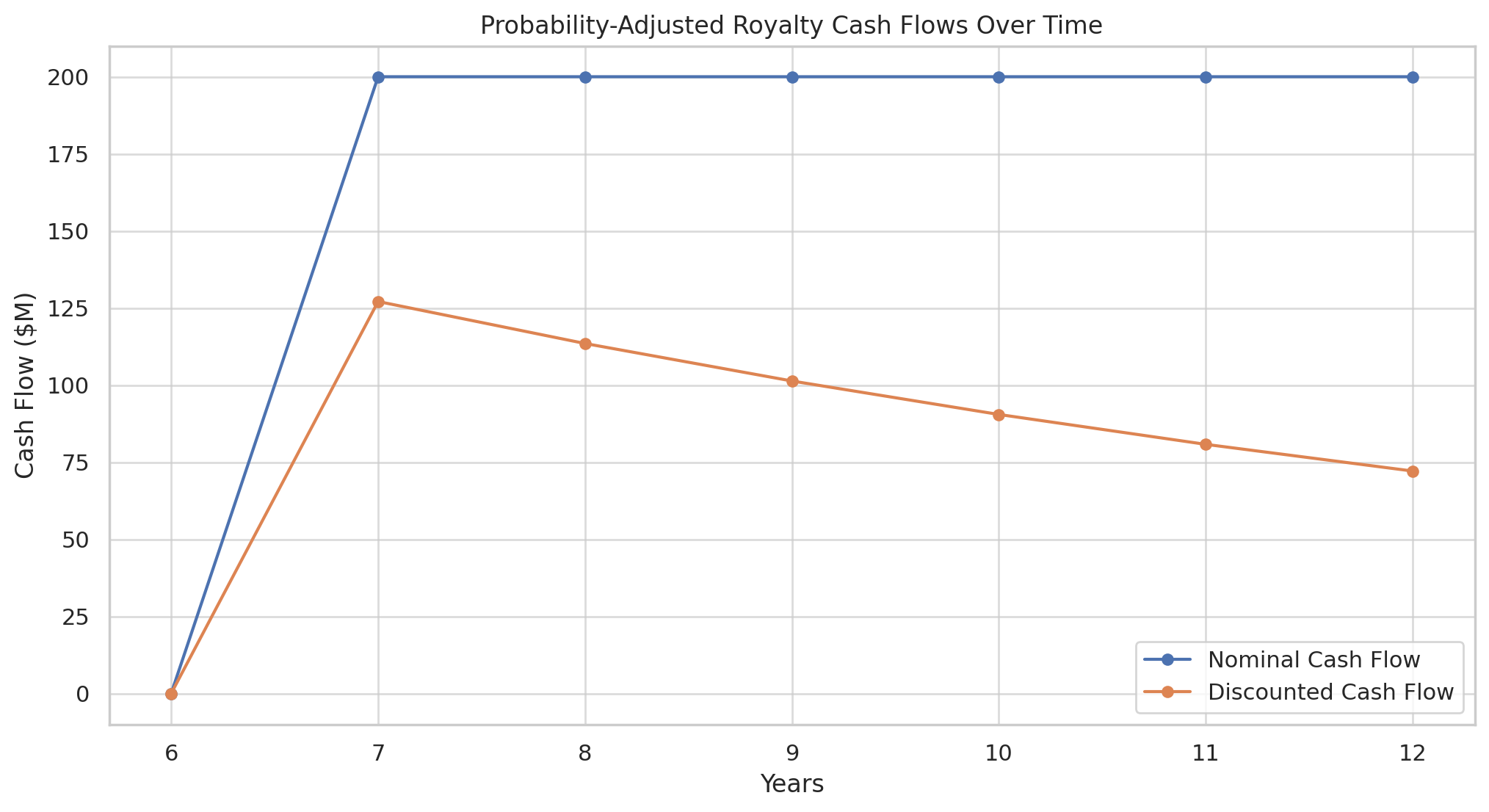

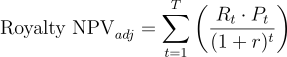

A more fine-tuned method favored in pharma is risk-adjusted net present value. Rather than using a single blunt high discount rate, rNPV explicitly multiplies each future cash flow by the probability that the drug will actually reach that point. For example, if a drug is in Phase 2 with, say, a 30% chance of ultimately getting approved (based on historical success rates), one would take the projected royalty cash flows that would occur if the drug succeeds and multiply them by 0.3 (30%).

Those “expected” cash flows are then discounted at a lower discount rate that reflects mainly time value of money and commercial risk (but not clinical risk, since we handled that via probabilities). In formula form one might calculate:

This is a simplified representation assuming the big risk is at approval; more generally, one could multiply each phase’s cash flows by the conditional probability of getting that far, which is effectively the same concept. The advantage of the rNPV method is that it more transparently shows the impact of technical risk and allows updating the valuation as a drug moves through phases.

For instance, the probability of approval increases after a successful Phase 3, so the valuation would jump at that point (whereas in the high-discount-rate method, one might lower the discount rate after Phase 3 to simulate the same effect).

In both approaches, accurate forecasting of sales is another major challenge. Peak sales of a new drug can be extremely hard to predict years in advance, and they depend on factors like competition, market size, pricing, etc. Royalty investors often rely on in-house or consultant analysts (sometimes using sophisticated epidemiological models or analogs) to project a reasonable sales trajectory for the drug.

They will also consider the patent expiry or royalty term – once generics hit, sales might plummet, and royalty streams often effectively end or drop substantially. So the cash flow timeline usually has a definitive sunset.

Probability of Success

It’s worth highlighting how steep the attrition can be in drug development. On average, from the start of Phase 1 trials to FDA approval, only about 9–10% of candidates succeed (even lower in some tough disease areas). From Phase 3 (late trials) to approval, success rates might be on the order of 50–60% depending on the indication. These probabilities are well-studied from historical data and investors use them as benchmarks.

For example, if a Phase 2 oncology drug historically has a ~30% chance to make it to market, a royalty investor will incorporate that into the valuation (either explicitly via rNPV or implicitly via demanding a very high return).

The length of time to realization also matters: even if a drug succeeds, a Phase 1 asset might be 7–10 years away from generating sales, which heavily discounts its PV. Thus, early-stage royalty deals, when they happen, tend to be smaller and at steep discounts. Often early-stage royalties are sold at a fraction of what they could be worth if the drug works – essentially, the seller is trading a big unknown upside for guaranteed money now, and the buyer is taking a long-shot bet that could pay off huge or go to zero.

Example Valuation Calculation

Suppose a biotech is selling a royalty that would be 5% of a drug’s sales. If the drug, once launched, is forecast to peak at $500 million in annual sales, and generate, say, $2 billion in cumulative sales over a 10-year life, 5% of that would be $100 million cumulative royalties. Now, if it’s already approved and selling, an investor might discount those royalties at, say, 10% over the years – that might yield a present value around (hypothetically) $70 million.

The investor might pay somewhat less than that (to target a higher IRR), perhaps $60 million upfront, expecting to turn $60 million into $100 million of royalty over a decade. If the drug is not yet approved, the investor will first scale that $100 million by the probability of approval. If the chance of approval is 50%, then the expected royalties are $50 million, and discounted maybe at 15–20% (because of higher risk and longer wait). That present value might be only $20–30 million, so the upfront price offered might be in that ballpark. This illustrates how risk and time delay dramatically reduce the payable amount for earlier-stage assets.

Competition and Market Factors

Investors also incorporate macro-factors such as potential competition (if a rival drug could cut into sales), regulatory changes (like drug pricing reforms), and even patent litigation risk. If a key patent might be challenged, that will be factored in (sometimes via scenario analysis or a higher discount rate). Some investors use option pricing models or Monte Carlo simulations for very uncertain cases, treating the drug’s success as an option with binary outcomes.

Notably, the rising interest rate environment in 2022–2023 affected royalty valuations: higher benchmark rates mean investors demand higher returns, all else equal. Indeed, observers noted that as interest rates climbed to multi-year highs, royalty deal discount rates also increased, making capital more expensive and moderating deal volumes somewhat (gibsondunn.com).

Conversely, when rates were very low (2019–2021), investors were willing to pay higher prices (accept lower yields) for reliable royalty streams, because fixed-income alternatives were scant. This partially explains why some large deals happened in 2020–21: money was cheap, and a secure royalty on a drug could be priced richly (good for the seller).

The Secondary Market for Royalties

Royalty interests, once created, can be bought and sold in secondary transactions. The initial deal where a royalty is created or first sold (an “origination” deal) is not the end of the story – investors can later trade these assets to optimize their portfolios or realize gains. In fact, a significant number of royalty deals each year are secondary purchases: one investor selling a royalty stream to another.

Origination vs. Resale

In an origination transaction, the royalty is sold by the operating company or original royalty owner directly to an investor. In a resale (secondary) transaction, a royalty that was previously owned by someone (an investor or institution) is sold again to a new buyer. An example of origination would be a biotech selling a royalty on its product to an investor. An example of resale is when that investor, a few years later, decides to sell that royalty to another party (or back to the biotech, or to a fund).

Over the past five years, the secondary market has also grown, though not as explosively as originations – one analysis showed resale deal value grew at ~15% annually, slower than the ~45% for originations, and resales have generally mirrored the same trends.

Secondary deals can be large as well: one famous case was in 2016 when Royalty Pharma bought the royalty rights that UCLA held on the prostate cancer drug Xtandi for $1.14 billion (zs.com). UCLA had originally licensed Xtandi to Medivation (then Pfizer); this was essentially UCLA cashing out its future royalty stream to Royalty Pharma. Another instance: in 2023, Royalty Pharma acquired a royalty stake in Merck’s COVID-19 antiviral Lagevrio from a patent trust (which was a secondary holder) for $130 million – a resale prompted by that trust’s desire to monetize an asset it received earlier.

Marketplaces and Process

Unlike stocks or bonds, there isn’t a public exchange for drug royalties – these are typically private transactions. However, the process often resembles an auction or bidding facilitated by investment bankers. A royalty owner (say, a university or small company) might quietly solicit bids from several royalty funds. Firms like DRI Capital or Sagard have in the past participated in competitive bidding for attractive royalty streams. The secondary market provides liquidity: an investor who initially bought a royalty and now wants to exit can do so by selling to another fund or even issuing royalty-backed securities.

There have been cases where royalty streams were securitized into bonds (known as “royalty-backed notes”) and sold to multiple investors – though this is relatively uncommon in biotech (one early example was BioPharma Credit PLC issuing notes backed by a pool of royalties). More frequently, large royalty funds like Royalty Pharma function as quasi-market-makers: they’ll buy out smaller holders. For instance, smaller funds or universities often sell to Royalty Pharma, which has a big war chest. Royalty Pharma itself in 2020 listed on NASDAQ, partly to provide liquidity to its investors and raise capital to keep acquiring royalties.

Valuation in Secondary Sales

When a royalty has been partially “seasoned” (i.e., some royalty payments have already been made and the drug’s performance is clearer), the value in a resale will reflect updated expectations. If the drug is outperforming its original forecast, the royalty’s value might be higher and the original investor can sell at a profit. Conversely, if sales disappointed, a resale might fetch less. For example, PDL BioPharma – a pioneering royalty fund – in the 2010s traded at a discount when some of its key royalty streams (like on the drug Avastin) underperformed; ultimately it wound down and sold its remaining royalties to other investors.

This highlights that royalties are financial assets subject to re-valuation over time. Importantly, secondary buyers will also evaluate risks like patent life remaining. A royalty that has, say, 5 years of patent protection left will be valued for that finite horizon. In contrast, a royalty on a biologic drug that might enjoy market exclusivity for perhaps 10–12 more years could command a higher multiple. Secondary transactions thus require careful due diligence on the current status of the product (Is it still growing? Any new competitors? Any safety warnings? etc.).

Scale of Secondary Market

While growing, secondary deals have generally been a smaller share of total activity than originations. They tend to spike when an original holder has a motivation to sell (e.g., a biotech needs cash and decides to sell a royalty they had retained on another company’s product). According to industry data, aside from one outlier year (2016, due to the huge Xtandi deal), the trend in resale deal value roughly tracks origination trends (zs.com). This implies that as more origination deals happen, a pipeline of secondary opportunities is naturally created a few years down the line.

In summary, the secondary market for drug royalties adds an element of liquidity and price discovery. It allows initial royalty investors to exit and new investors to step in. It also underscores that a royalty stream, once created, is a tradeable asset – subject to changing hands as market conditions and risk appetites evolve.

Financing and Returns for Royalty Investors

How do royalty investment firms finance these large upfront payments, and at what cost? The business model of a royalty investor is to deploy capital into purchasing royalty streams that yield a higher return than the cost of that capital. Different investors have different capital sources:

Private Fund

Many royalty investors operate as private equity or venture funds dedicated to healthcare royalties. For example, HealthCare Royalty Partners (HCR) and DRI Capital raise pools of capital from limited partners (LPs) such as pension funds, endowments, and family offices. These LPs commit money with the expectation of returns often in the low-to-mid teens percentage per year over the fund’s life (to justify the illiquidity and risk).

The royalty fund then uses these committed funds to buy royalties. In essence, the LPs are providing equity capital that does not need to be paid back like a loan, but they expect, say, ~15% IRR (internal rate of return) on the portfolio. This expected return sets a baseline for how the fund prices deals – they will aim to achieve deals that collectively can deliver that IRR after fees.

Publicly Traded Royalty Companies

The biggest example here is Royalty Pharma plc, which is publicly listed (Nasdaq: RPRX). Royalty Pharma has permanent capital from its shareholders and also access to debt financing. As of the end of 2024, Royalty Pharma carried about $7.8 billion of debt on its balance sheet (sec.gov), demonstrating substantial leverage to fund acquisitions.

It has an investment-grade credit rating (rated BBB- by Fitch and S&P), which means it can borrow at relatively moderate interest rates (on the order of perhaps 5–6% annual interest, subject to market conditions). For instance, Royalty Pharma has issued multi-billion-dollar senior notes and maintains a $1.5 billion revolving credit facility to draw on for deals (royaltypharma.com).

The ability to borrow cheaply gives it a lower cost of capital. If it can borrow at, say, 5% and invest in a royalty deal that yields 10–12%, the spread accrues as profit (simplistically speaking). Royalty Pharma also uses equity – it raised ~$2.2 billion in its 2020 IPO, and can issue new shares if needed – though it generally prefers debt given its cash flows. Other vehicles like BioPharma Credit plc, traded on the London Stock Exchange, raise capital from public markets to invest in royalty debt deals (providing investors a dividend from the interest/royalties received).

Strategic and Other Investors

Large asset managers and pension funds sometimes invest directly or via co-investment. For example, CPPIB (Canada Pension Plan) has co-invested in royalties; OMERS launched a royalties fund. These players often have a low cost of capital (they might be content with single-digit returns if the risk is low). When they step directly into bidding, it can push deal prices up (reducing the yield). Pharma companies themselves occasionally act as investors, especially in “clinical funding” deals for other companies’ drugs – essentially, they fund a smaller company’s trial in exchange for a royalty, as a strategic investment.

Refinancing and Financial Engineering

Royalty deals can be refinanced similar to loans. An investor who owns a stream could potentially borrow against it. In fact, in some deals the investor might syndicate the risk: for instance, Royalty Pharma could buy a royalty and later sell a percentage of that royalty to another fund or issue bonds backed by it. This way, they free up cash to do more deals.

There have been cases where a royalty stream on a big drug was used to issue asset-backed securities. Moreover, if interest rates drop, a leveraged royalty investor might refinance its debt to lower rates, improving net returns. Conversely, rising rates can squeeze their spread.

Target Returns

What rates do royalty investors actually target? It varies by stage and risk. For marketed, stable products, investors might be satisfied with high single-digit to low-teens annual returns. For instance, a portfolio of very reliable royalties might only yield 8–10%, but that’s attractive to income-oriented investors, especially if uncorrelated with stock markets (seekingalpha.com).

For riskier or early-stage assets, investors seek higher potential IRRs, often above 20%. Essentially, the required return is inversely related to the asset’s certainty. This aligns with the discount rate discussion: early-stage deals were valued with ~30–40% discount rates (implying they’re targeting that kind of return if it succeeds).

However, keep in mind that if the drug fails, the realized return is negative (a loss), so those high rates reflect the need to compensate for risk of failure. Royalty deals are often modeled in a probabilistic way: an investor might say “there’s a 30% chance I lose everything (IRR -100%), a 20% chance of mediocre sales (IRR 0–5%), and a 50% chance of good sales (IRR 20%+). We price it such that the weighted-average IRR meets our hurdle.”

Comparison to Other Financing Rates

It’s useful to compare what a biotech would pay in alternatives. Traditional debt financing for a small biotech is usually not available without collateral – and if it is (venture debt), it often comes with 8–12% interest plus equity warrants, effectively a high-teens cost when risk is factored (cov.com).

Equity is even more expensive in terms of cost of capital (venture capitalists expect 20–30% returns or more for early-stage equity). Royalty financing, thus, slots in as a middle option: not as dilutive as equity, and in some cases cheaper than issuing stock at a low valuation. From the investor side, they view royalty streams as yielding better than corporate bonds. A BBB-rated bond (investment grade) in pharma might yield, say, 4–5%; a royalty provides a chance at 10%+. This spread is the reward for the complexity and risk.

Refinancing Example

Consider Royalty Pharma’s own finances. With a BBB- rating, Fitch notes that “Royalty Pharma faces valuation risks in acquiring new products, with potential impacts from product safety or liability issues” that could hurt its cash flows (fitchratings.com).

Yet its diversified portfolio of royalties (on many drugs) provides stable cash flow to service debt. The company can raise debt at moderate rates and has no near-term need to issue equity, according to its 2025 guidance (they assumed no additional debt financing in 2025, implying comfortable liquidity).

By maintaining a low weighted average cost of capital, Royalty Pharma and peers can keep doing deals. Another firm, XOMA (a smaller royalty aggregator), funds its purchases mostly via equity capital and reinvestment – it doesn’t carry large debt, but it also does smaller deals, often on early-stage assets, aiming for very high eventual returns to make up for a low hit rate.

In summary, royalty investors arbitrage capital costs: they gather money from sources expecting, say, 8–15% returns, and deploy it into deals that, if structured well, can yield in the mid-teens or higher. The difference, minus any losses on failed assets and operating costs, is profit.

The health of this model depends on accurate risk assessment – overpaying for a royalty (thus yielding too low a return) or taking on too much debt can spell trouble if the drug underperforms. We have seen cases where investors had to write down royalty assets (for instance, if a drug is pulled from the market, the royalty value plunges). Therefore, firms often keep some cushion and diversify across many deals.

“Talebian” Critique – Risks and Potential Weak Points

While royalty deals can seem like win-win financial engineering, it’s important to critically assess their fragility and hidden risks. A perspective inspired by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (known for highlighting “Black Swan” events and fat-tail risks) would point out several potential weak points in the royalty financing model:

Overreliance on Forecasts

Royalty valuations are only as good as the sales forecasts and probability estimates that underpin them. However, drug sales and approvals are notoriously hard to predict – history is rife with blockbuster drugs that came out of nowhere, as well as highly touted drugs that failed spectacularly. Taleb and others have noted that conventional forecasting often underestimates the likelihood of extreme outcomes (hbr.org).

In the context of royalties, a “black swan” could be a sudden safety issue (e.g., an approved drug is found to have a rare fatal side effect and gets withdrawn) or a regulatory shock (such as a new law that slashes drug prices) that wipes out a huge portion of the expected cash flow.

Investors and models may treat such scenarios as very low probability – until they happen, and then the models break. As one risk expert put it, “We don’t live in the world for which conventional risk-management textbooks prepare us” (hbr.org). In other words, the real world can deliver surprises outside the range of what the models assumed.

Binary Risk and Tail Distribution

Especially for development-stage deals, the outcome is almost binary (drug gets approved and succeeds, or it fails and produces near-zero royalty). This is a highly skewed risk distribution. A Talebian view would argue that aggregating a few such bets might not meaningfully reduce risk if those bets are correlated or if the probability of failure is underestimated. For example, many biotech projects could all fail due to a common factor (if, say, an entire scientific approach turns out to be flawed – consider the rash of Alzheimer’s drug failures in the past).

Royalty portfolios could thus be less diversified than they seem – a true black swan like a regulatory clampdown on drug prices or a pandemic disrupting healthcare can affect multiple royalties at once. (During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, sales of some drugs dropped sharply due to fewer doctor visits, which would have been an unexpected shock to royalty holders.)

The fragility is that while returns look stable in normal times, in extreme scenarios the downside could be larger than anticipated. Even Fitch Ratings, in evaluating Royalty Pharma, cautioned that unforeseen product safety issues or liability events could impair its royalty streams (fitchratings.com) – essentially warning of tail risks specific to pharma products.

Valuation Risk – “The risk of overpaying for certainty”

Royalty deals on approved drugs are sometimes priced very richly (low yields) because they are perceived as safe – nearly bond-like. A skeptical view is that investors may be overpaying for the illusion of predictable returns, making a classic mistake of underestimating risk. Royalty Pharma, for example, faces this dilemma: if it pays too high a price (thus accepting a low return) for a secure asset, any negative surprise will disproportionately hurt the investment’s value. As an analysis by Intelligent Investor noted, the risk for Royalty Pharma is “overpaying for certainty” – paying so much that there’s little room for error (intelligentinvestor.com.au).

In financial terms, if you buy a royalty yielding, say, 8% expecting it to be rock-solid, and then a patent challenge or competitor cuts the sales in half, your effective return might drop to 0% or worse. Thus, a seemingly safe asset can harbor big downside if rare events occur. Taleb’s critique of risk models is apt: models might assign a tiny probability to such events, but in reality their frequency or impact can be greater than assumed, rendering the average projections overly optimistic.

Illiquidity and Leverage

Another weak point can be the combination of illiquidity and possible leverage. Once an investor commits capital to a royalty, it’s not as liquid as a stock; selling it (as a secondary deal) takes time and depends on finding a buyer. If multiple things go wrong simultaneously (say a fund holds royalties in five drugs and three of them encounter problems), the fund can be strained.

If the investor has also borrowed money to finance deals (as many do), a drop in royalty income could create financial stress – much like mortgage-backed securities did in 2008 when underlying assumptions failed. Royalty Pharma’s use of debt, for instance, means it must manage cash flows carefully; a Taleb-inspired view would be cautious of any mismatch between short-term obligations (debt payments) and long-tailed, uncertain royalty incomes. Should a severe event occur (for example, a major royalty contributor in Royalty Pharma’s portfolio loses patent protection earlier than expected), the company could face difficulties if it has leveraged that income.

Model Risk and Complexity

Royalty deals often involve complex contract terms (caps, tiers, buyouts) that can make the cash flow pattern complicated. This complexity can obscure how sensitive the returns are to various factors. It might be hard for outsiders – and sometimes even the parties themselves – to fully grasp the embedded optionality and how it behaves under extreme conditions. A Talebian critique would be that complexity can lead to an illusion of control: lots of clauses and conditions might give a sense that risk is well managed, but they could fail in unanticipated ways.

For example, consider a cap and tail structure – it might protect the company in extreme upside scenarios and protect the investor in mild downside scenarios, but in an extreme downside (drug failure), all those structured provisions don’t help – it’s simply a loss. In other words, no financial engineering can escape the fundamental risk that a drug might not deliver at all.

In plain terms, royalty financings concentrate a bet on the success of one product or a set of products. They transfer the bet from the company (or inventor) to the investor, which can be mutually beneficial under expected scenarios. However, the Talebian view is that one must examine how the arrangement holds up in the tails of the distribution – the low-probability, high-impact events.

Are those risks truly as low as assumed, and who ultimately bears them? In royalty deals, if a black swan event hits (say, a once-in-a-generation regulatory change that, for example, allows the government to void certain drug patents or enforce price controls), the investors could face large losses, and any companies depending on that cash might be hurt too (if they already spent the upfront).

It’s worth noting that many royalty firms mitigate these risks via diversification – holding royalties on dozens of drugs across therapy areas, so that a blow-up of one asset doesn’t sink the whole ship. Royalty Pharma, for instance, has royalties in oncology, neurology, rare diseases, etc. The idea is that it’s unlikely for all drugs to face unexpected trouble simultaneously.

Nonetheless, systemic risks (like broad healthcare reforms or macroeconomic collapses) could affect many assets at once. Moreover, diversification can lead to mediocristan (bell-curve) thinking, whereas drug outcomes might live in extremistan (power-law outcomes, where a few big winners and losers dominate). Nassim Taleb often emphasizes that models assuming a nice bell curve of outcomes can grossly misprice extreme risk.

In conclusion, the “straight facts” analysis shows royalty deals as a powerful financing tool with clear benefits, but a Talebian lens reminds us that the devil is in the tail. The fundamental vulnerability is that these deals are only as good as the continued success of a highly uncertain enterprise – drug development and commercialization. While they shift risk and carve up financial rights in innovative ways, they do not eliminate risk.

Unpredictable events (a black swan in drug research or regulation) can undermine the theoretical stability of royalty streams. Investors and companies participating in these deals must thus be mindful of worst-case scenarios, stress-testing their assumptions. As Taleb would advocate, one should “expect the unexpected” and not be lulled by a long period of steady royalty payments into thinking that the risk has vanished. Each deal carries its own fragility, and only with rigorous analysis and prudent structuring (and a healthy respect for the unknown) can those risks be managed – but never fully wished away.

Member discussion