Basics of Pharma Deal Structuring: An Explainer for Biotech Professionals

Most biotech professionals are familiar with science and R&D, but deal press releases often include financial jargon that can be confusing. In this explainer, we’ll break down common finance terms and concepts relevant to pharma/biotech deal structuring – equity vs. debt financing, senior notes, covenants, debt preferences (priority in repayment), liquidity events, stock options, and warrants – and illustrate how they appear in real-world deals.

We’ll focus on early-stage biotech scenarios as well as big-pharma transactions, using recent examples (with charts and graphs where helpful) to show what these terms mean in practice.

Equity vs. Debt Financing in Biotech

Equity financing means raising capital by selling ownership shares in the company (e.g. stock). Debt financing means borrowing money (e.g. via loans or bonds/notes) that must be repaid with interest. Biotech companies use both, but the mix often depends on their stage and financial profile.

Early-stage biotechs (startup and pre-revenue companies) rely mostly on equity funding (venture capital, angel investors, etc.) because they usually have little or no revenue to service debt. Investors buy shares (common or preferred stock) providing cash to the company, and in return they expect a share of future profits or an “exit” payoff. Debt is less common at this stage – banks are reluctant to lend to pre-revenue companies, and startups can’t easily pay interest. As one legal review notes, life science startups “are not usually well suited to debt financing” due to lack of revenue, but as they grow and start generating some revenue, venture debt from specialized lenders can become an option.

Established pharma/biotech companies (especially public companies with product revenue) can and do use debt financing frequently. Large pharma companies often issue bonds or notes to raise huge sums at low interest rates, especially to fund acquisitions or expansion. For example, in 2023 Pfizer announced a $31 billion debt offering (one of the largest ever) to help finance its $43 billion acquisition of Seagen (reuters.com). Likewise, AbbVie raised $30 billion debt in 2019 to buy Allergan. These companies have steady cash flows and credit ratings, so they can borrow cheaply.

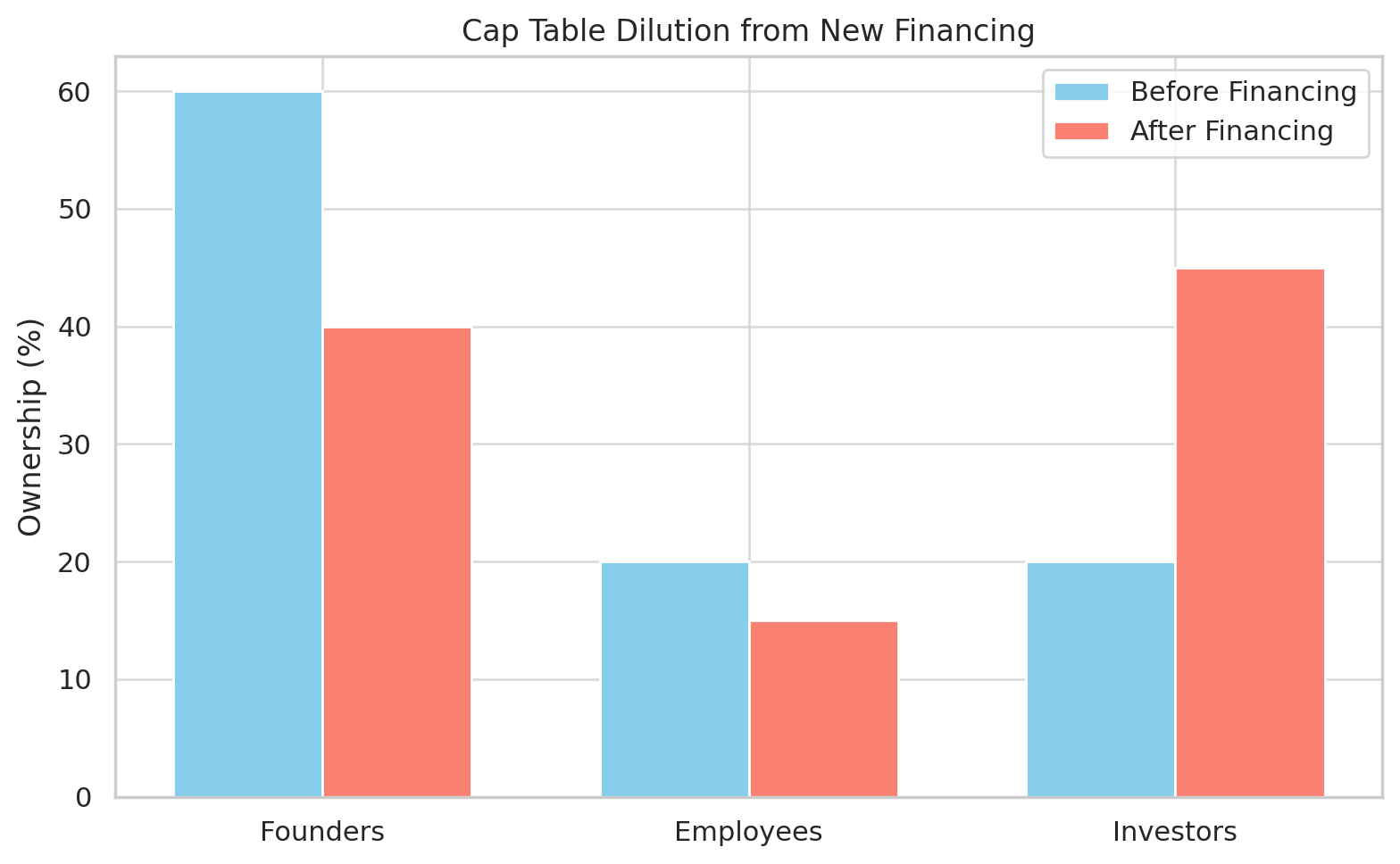

Why choose equity vs. debt? Equity doesn’t need to be repaid and doesn’t add immediate financial strain – crucial for a cash-burning biotech – but it dilutes ownership (founders’ and existing shareholders’ percentage stakes shrink). Debt, on the other hand, must be repaid with interest, creating a fixed expense, but allows the company to raise money without diluting ownership. Established companies often prefer debt for large financings because it can be cheaper than equity (interest is tax-deductible, unlike dividends) and doesn’t give up control.

However, too much debt is risky – if a company can’t meet interest or principal payments, it faces default or bankruptcy. Thus, companies must balance the two. It’s common to see hybrid instruments too – for instance, convertible notes (debt that can turn into equity under certain conditions) used in both startup financing and by public biotechs.

Example – Early-Stage Equity vs. Debt

A young biotech startup will typically raise a Series A equity round from VCs rather than take a bank loan. The VC gets preferred stock (with special rights we’ll discuss) in exchange for funding the next phase of R&D. The startup likely has no revenue to pay loan interest – equity is the only viable route. In contrast, a mid-stage or public biotech with a promising drug might take on venture debt from a specialized lender alongside an equity round. Venture debt often comes after a VC round and provides extra cash with minimal upfront dilution.

Lenders know it’s high risk, so such loans often include an “equity kicker” (warrants or convertible features) to compensate (more on warrants later). For instance, Bird & Bird’s analysis notes that venture debt deals in life sciences “usually involve an equity element, either in the form of convertible debt or warrants to subscribe for shares in the future”, giving the lender upside if the company succeeds.

Example – Big Pharma Financing

Large pharma companies commonly issue corporate bonds (notes). These are typically senior unsecured notes (explained below) repayable in set terms (5-year, 10-year, etc.) with semiannual interest. For example, Pfizer’s $31B multi-tranche offering in 2023 consisted of notes due in 2 to 40 years with various fixed coupons (pfizer.com). The cash raised is used for strategic purposes (like Pfizer’s Seagen acquisition).

Investors in these notes are usually institutions attracted by the steady interest. Because Pfizer is investment-grade, these notes had relatively low interest spreads (e.g. the 10-year bond was issued at ~1.25% above U.S. Treasuries). Big companies can also raise equity (e.g. a secondary stock offering), but that’s less common for cash-rich pharma unless funding a very large deal or if debt capacity is maxed out.

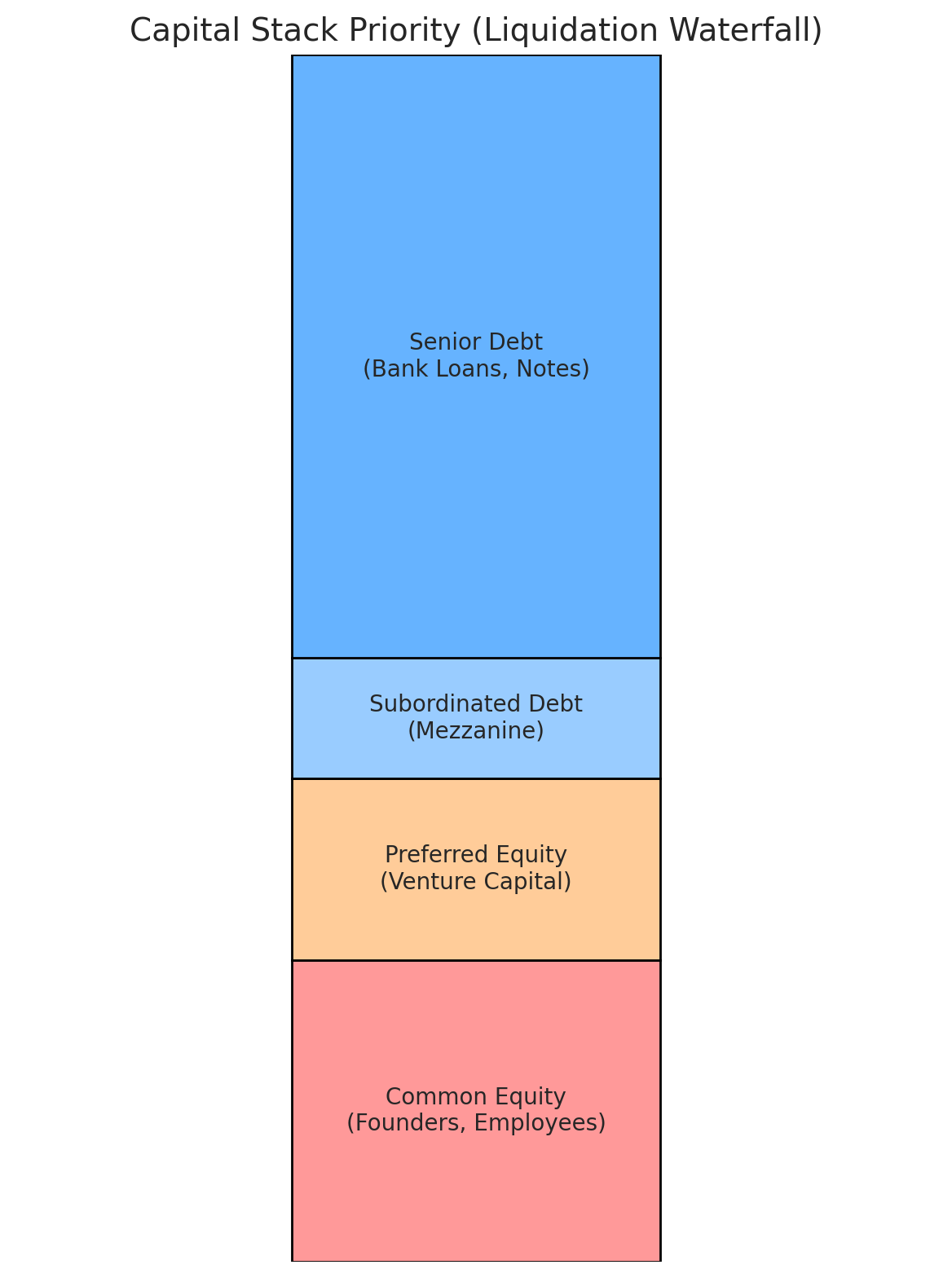

The Capital Stack: Debt “Preferences” vs. Equity

In any company, there is a capital stack – a hierarchy of claims on the company’s assets and earnings. Understanding this hierarchy is key to terms like senior, subordinated, or preferred. Simply put, debt has priority (preference) over equity in getting repaid. Within debt, senior debt ranks above junior/subordinated debt. And within equity, preferred stock (if issued) ranks above common stock.

“Debt preferences” – while not a formal term – refers to the preferential treatment debt holders get. If a company runs into trouble or liquidates, debt holders are paid first, before equity holders. This is why debt is considered “safer” for the investor (but from the company’s perspective, defaulting on debt can lead to bankruptcy or asset seizure). Equity holders are last in line – they get whatever is left only after all debts are paid. In finance, we say debt has a senior claim on assets.

Within the debt category, there are layers:

- Senior debt/notes – Highest priority. Often secured by assets or, if unsecured, still senior in right of payment to other debt. Holders of senior notes must be paid in full before subordinated debt gets anything if the company fails. Because of this safety, senior debt usually carries lower interest rates.

- Subordinated (junior) debt – Lower priority, paid after senior debt. Subordinated lenders take more risk and thus often charge higher interest.

Within equity:

- Preferred stock – Equity that carries special rights, often including a liquidation preference (discussed below). Preferred shareholders get paid out (up to a certain amount) before common shareholders in a liquidation or sale event.

- Common stock – The ordinary shares (usually held by founders, management, employees, public investors in a public company). Common shares are last in priority; they get whatever value remains after all debts and preferred claims are satisfied. Common stock has the highest risk (it can be wiped out) but also unlimited upside if the company becomes hugely valuable.

This hierarchy is often illustrated as a stack or pyramid of funding layers. The lower layers (senior debt) are lowest risk and get paid first (but have capped returns – just repayment + interest). The upper layers (equity) are highest risk (paid last, and possibly nothing in a downside scenario) but have unlimited return potential (in a big success, equity holders reap the gains after debts are paid).

Capital stack illustration: Debt sits at the bottom of the stack (senior debt, then subordinated debt above it), and equity at the top. In a liquidation, the stack pays out from bottom to top – senior debt first, then junior debt, and equity last. The increasing height of coin stacks (with % signs) on the right symbolizes that as you go up the stack, the risk increases – and so do the required returns or potential upside. Senior debt has lowest risk/return, equity has highest.

Senior Notes

In many press releases, you’ll see terms like “senior notes” or “senior secured notes.” A senior note is simply a corporate debt security (a type of bond or loan) that ranks at the highest priority for repayment. It’s “senior” to other debt, meaning if the company can’t pay all obligations, holders of senior notes get paid before holders of, say, subordinated notes or other unsecured claims. In other words, senior notes are top-tier IOUs. For example, if a biotech issues a senior note to investors, it is promising that those noteholders have first claim on the company’s assets (or cash flows) up to the amount owed.

Real-world example: BridgeBio Pharma’s 2025 debt refinancing – BridgeBio announced $500 million of convertible senior notes due 2031 to refinance existing term loans (investor.bridgebio.com). In the press release, they explained the new notes would be senior unsecured obligations, ranking senior to any future subordinated debt, equal with the company’s other unsecured debt, and effectively junior to any secured debt (debt that has collateral backing). This means:

- If BridgeBio later issues some subordinated debt, those new lenders would stand behind the 2031 notes in priority.

- The 2031 notes are unsecured (no specific collateral), so if the company has also borrowed against specific assets (secured debt), the secured lenders have first rights to those assets – making the unsecured notes effectively junior to that extent.

- The notes are also structurally junior to subsidiary liabilities (meaning if BridgeBio’s subsidiaries have debt, that debt is paid before any claims of the parent company’s noteholders on subsidiary assets).

For a simpler picture: think of senior notes as being first in line among creditors. Subordinated notes would line up behind them. And equity holders line up last. A connected term is “senior secured” vs. “senior unsecured.” Secured means the debt is collateralized by specific assets (giving the lender the right to seize those assets if the company defaults). Unsecured means no specific collateral – the lenders have a claim just like any general creditor. An unsecured senior note still ranks above subordinated notes, but if there is a secured loan, the secured lender can claim the collateral first.

From an investor perspective, senior notes are safer; from the company’s perspective, senior notes impose strict obligations but are cheaper (lower interest) than riskier funding.

As Cobrief’s plain-English glossary (cobrief.app) puts it: “When a company issues senior notes, they are borrowing money from investors and promising to pay it back with interest. If the company goes bankrupt, the holders of senior notes get paid before those with other types of debt, like subordinated or junior notes.”.

“Debt preferences” in practice

The priority of debt claims is why we say debt has preference. For example, if a biotech unfortunately goes into liquidation with $10 million in remaining assets, and it owes $7M to a bank (senior debt) and has equity investors, the $7M from asset sales goes entirely to pay off the bank first.

Equity holders likely get nothing (their share is wiped out). Even among multiple debts, senior ranking matters: if there was also a junior lender owed $5M, the senior lender might get paid in full and the junior lender would only get what’s left (in this case $3M, a shortfall). Thus, having a “senior” position is a lender’s way to ensure they have first dibs on value.

It’s important to note that preferred equity in venture deals also creates a type of preference (not debt, but a preference over common stock). We’ll cover liquidation preferences shortly – which are essentially an agreed “preference” amount that equity investors get before common shareholders receive anything in an exit. This concept sometimes confuses folks because it sounds like debt, but it’s actually an equity term in VC financings.

Covenants: The “Rules of the Game” in Debt Deals

When a company borrows money (debt financing), the loan or note agreement typically includes covenants – which are conditions or rules the company (borrower) must adhere to. Covenants are there to protect the lender by ensuring the company stays financially healthy enough to repay or doesn’t take actions that could jeopardize repayment.

If the company breaches a covenant, the lender can often declare a default, which may allow them to demand immediate repayment, seize collateral, or take other remedies. Thus, startups and companies must manage covenants carefully.

Common types of covenants

Financial covenants

Requirements to maintain certain financial metrics. For example, a minimum cash covenant (often called a minimum liquidity covenant) might require the company to keep at least $X million of cash on hand at all times. This assures the lender the company has a buffer.

For instance, Karyopharm Therapeutics disclosed that under its term loan, it had a $25 million minimum liquidity covenant – meaning it must keep $25M cash or equivalents, effectively not letting its cash balance drop below that (investors.karyopharm.com). Violation would be a default. Another example is limiting negative cash flow beyond a certain amount or requiring that the company’s net worth doesn’t fall below a threshold.

Debt and lien covenants

Restrictions on taking on additional debt or pledging assets. E.g., a covenant might say the company cannot incur new indebtedness or can’t create liens on assets without the lender’s consent (to prevent another lender from becoming senior or equal in claim).

The Biofrontera example of a $4.2M convertible note explicitly stated covenants that “limit the ability of the Company to (i) create liens, (ii) pay dividends or repurchase stock, (iii) incur indebtedness, or (iv) enter transactions with affiliates,” with certain exceptions. These are standard restrictions ensuring the company doesn’t undermine the noteholders’ position by, say, borrowing more and overleveraging, or giving away cash to shareholders while debt is unpaid.

Operational covenants

For example, requiring lender approval for major business changes or requiring certain reporting. Some venture loans require the startup to provide monthly financial reports or even undergo an annual audit. They might also mandate that the company achieve certain milestones or not deviate from its business plan without consent.

Positive vs. negative covenants: A positive covenant is something the company must do (e.g. provide financial statements regularly, maintain insurance). A negative covenant is something it must not do (e.g. not pay any dividends, not merge or acquire another company without approval, etc.).

Why covenants matter

They can have pros and cons. On one hand, agreeing to covenants might get the company a better interest rate or access to debt it otherwise couldn’t get (because covenants reduce lender risk). They also enforce financial discipline – e.g. a minimum cash covenant forces management to always keep a cash buffer. On the other hand, covenants limit operational flexibility.

A startup might be constrained from making a strategic move because it would breach a covenant, or it might have to constantly monitor its metrics and spend time negotiating waivers if it comes close to breaching.

Example – Covenant in action

The Karyopharm case is illustrative. Karyopharm had to state its cash runway excluding certain uses because it needed to maintain that $25M minimum cash by lender requirement (investors.karyopharm.com). Essentially, even if the company technically has cash that could last into 2026, it can’t actually use the last $25 million of it – that portion must remain untouched to satisfy the loan covenant.

If it dropped below $25M, the lender could declare default. Another common covenant for pre-profit biotechs is requiring that new equity raises happen by a certain date (to ensure fresh capital comes in), or that revenue stays above a low threshold if any revenue exists.

If covenants are breached and default happens, consequences range from penalties, higher interest, to as severe as the lender calling in the loan (demanding immediate repayment) or even forcing bankruptcy. Often, breaches can be negotiated or waived if the company and lender work out a deal (especially if it’s a slight breach), but it’s a serious situation to avoid. Default remedies are not fun – the lender could potentially force the startup into bankruptcy or take control if things go really poorly.

In press releases, you won’t always see all covenant details (they are usually in the financing agreements), but sometimes companies mention when a financing eliminates prior covenants or increases flexibility.

For example, BridgeBio’s PR noted that by refinancing its secured term loan with the new convertible notes, it was terminating an agreement that “contains various restrictive covenants,” thus giving it “greater operational flexibility” going forward (investor.bridgebio.com). Investors like to know that a company isn’t handcuffed by tight covenants after a refinancing.

Liquidity Events and Liquidation Preferences

In the context of startups and VC investors, you’ll often hear about “liquidity events” and “liquidation preferences.” These go hand in hand. A liquidity event is any event that allows equity holders to convert their stake into actual cash – typically an acquisition of the company or an IPO (or less commonly, a merger or even company dissolution). Essentially, it’s an “exit” – the point at which early investors and founders can liquidate their otherwise illiquid shares for money.

For example:

- If Big Pharma Co. acquires Startup Biotech for $100 million, that acquisition is a liquidity event – the purchase price flows to the startup’s shareholders.

- If a biotech goes public via IPO, that’s a liquidity event – shares become freely tradable on a market, allowing investors to sell and cash out (at least partially).

Why it matters: VCs invest expecting a liquidity event down the line (they don’t get dividends usually; they profit when the company is sold or goes public). Press releases might mention these in contexts such as “investors have the right to require redemption of notes upon a change of control or IPO” – which are liquidity events triggering certain contract terms.

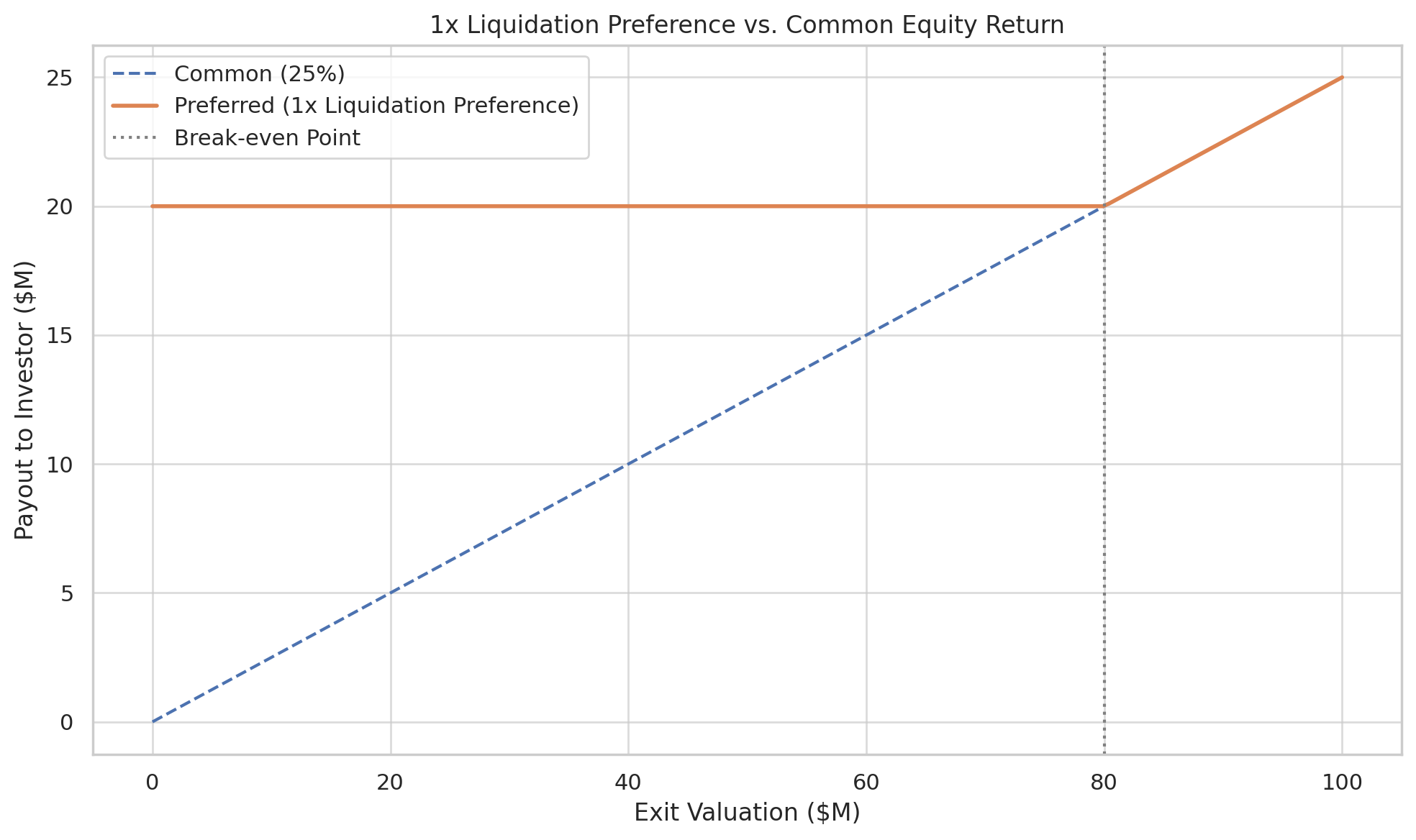

Now, liquidation preference is a term specific to preferred equity (usually in venture financings). A liquidation preference is a right that gives investors (holders of preferred stock) a certain payout before common stockholders if a liquidity event occurs. It’s basically downside protection for investors.

In the simplest form, a 1× liquidation preference means the investor gets back at least the amount they invested (1x their money) before common shareholders get anything, in an exit or liquidation. Only after the preferred investors receive their preference amount do the remaining proceeds (if any) get shared with common stock.

Let’s break that down with an example scenario

A biotech raises $5 million from a VC for 25% of the company, with a 1× non-participating liquidation preference on those shares (this is a common term). “Non-participating” means the investor either takes their preference or converts to common for their 25%, whichever is higher – they don’t get to double-dip.

If later the company is acquired for, say, $10 million (a relatively low outcome): With a 1× pref, the VC is entitled to get $5 million off the top (their original $5M back) before the remaining $5M is distributed. So the VC would take $5M, and the remaining $5M would go to the others (founders/common).

In this case, the VC’s 25% equity would have only been worth $2.5M without a preference, so the preference boosted their payout to $5M – they effectively recouped their full investment, leaving common shareholders with much less ($5M instead of $7.5M they’d have split pro rata without prefs). In fact, if the sale price were below $5M, the VC with 1× pref would get whatever the sale price is (up to $5M) and common would get zero. This shows how in a weak exit, preferred investors can take the lion’s share due to liquidation preferences.

If the company sells for a high price, say $100 million: The VC would compare its pref vs. its share of proceeds. 1× $5M = $5M, whereas 25% of $100M = $25M. Obviously $25M is better, so the VC would convert to common (waiving the preference) and take $25M.

In a good outcome, the preference doesn’t limit the upside; it mainly helps in low outcomes. Non-participating prefs ensure the investor either gets their money back or their ownership share’s worth – whichever is greater.

In summary, a standard 1× liquidation preference guarantees the investor the first cut of the exit proceeds, up to the amount they put in (sometimes with a multiple or interest). It’s called a preference because it preferences them over common stockholders.

The “liquidation waterfall” is the order of who gets paid what in an exit. By default (with no prefs), all shareholders would just split proceeds pro rata. But with prefs, the waterfall is altered: pay out the prefs first, then divide any remainder.

The liquidation waterfall sets out the order of distributions on a sale or liquidation. The default is pro rata, but investors almost always negotiate a liquidation preference – the amount an investor will receive on a sale or liquidation before any proceeds go to holders of ordinary (common) shares. It’s usually expressed as a multiple (typically 1×) of the original investment.

Often it can include an accruing dividend or higher multiple (e.g. 1.5× or 2×) in riskier climates.

Multiple preferences: If an investor had a “2× liquidation preference” on that $5M investment, it means they want $10M off the top at exit before common gets anything.

This can severely skew outcomes in moderate exits. If your investor puts in $5M and asks for a 2× liquidation preference, they want to take the first $10M of value off the table when you hit a liquidity event.

Only after they get $10M would the rest go to common. That means any sale below $10M, the investor essentially takes it all; at $10M, they take the full amount; at $30M, they’d take $10M and the remaining $20M goes to others, etc.

The investor would only consider converting to common (20% ownership in that scenario) if the exit is high enough that 20% of it exceeds $10M (in this case above $50M).

Participating vs. Non-participating

Non-participating (as described above) means the investor either takes their pref or their share of the pie, whichever is more, but not both. Most VC deals today use non-participating prefs (which is more company/founder friendly).

Participating preferred means the investor gets to collect their preference, and then also share in the remaining proceeds with common, as if they had converted. This is double-dipping and very investor-friendly. For example, with 2× participating pref, the investor would get $10M off the top (using the $5M investment example) and still keep their 25% stake in whatever remains to split.

This can lead to the investor taking a much larger total portion. Participating preference is more rare and investor-friendly – often, only non-participating is given. Sometimes participation is “capped” (e.g. participate up to a total of 3× payout).

Impact on founders/common: Liquidation preferences protect investors in downside scenarios, but they mean founders and employees (common stock) might get nothing or very little in a modest exit. In an extreme case, if a startup raises multiple rounds with stacked preferences, a smaller acquisition can result in all proceeds going to investors (founders walk away with effectively zero because the preferences consume the entire price). This is why understanding the “liquidation stack” is crucial for entrepreneurs.

To visualize, here is a simplified chart of how proceeds from a hypothetical $10M acquisition might be distributed with and without a liquidation preference, for a company with $7M total invested (Series A $5M + Seed $2M) and the rest common equity value.

Liquidity events trigger the preferences

By definition, the liquidation preference comes into play at a “liquidity event” – which includes not just actual liquidation (bankruptcy), but any merger or acquisition (“sale of the company”) or sometimes an IPO. In an IPO, typically preferred stock automatically converts to common stock (since IPO means the company isn’t being sold for cash; it’s just going public).

However, the term “liquidity event” in many term sheets includes IPO as a trigger for conversion of preferred to common (since post-IPO the prefs go away and everyone holds common that they can sell on the market). It’s worth checking how a press release uses the term: often, if a company issues convertible notes or other instruments, they might say “upon a liquidity event (such as a change of control), the notes will be redeemable or convertible” etc.

For example, BridgeBio’s convertible notes indicated that holders have the right to require the company to repurchase their notes at 100% of principal + interest upon certain events (investor.bridgebio.com) – usually those events are a change of control or similar liquidity event.

That’s a protective clause for noteholders: if the company is sold, they can demand cash for their notes (rather than being stuck converting into possibly uncertain equity of the acquirer). It’s analogous to a pref in that debt investors also want protection during a big event.

In summary: When reading a deal press release about an early-stage financing:

- If it mentions “Series [X] Preferred Stock with a 1× liquidation preference,” know that means those investors are assured their money back first in an exit.

- If you see “liquidity event” or “exit”, think IPO or acquisition – the moment of truth when these preferences and terms determine who gets what.

- For big companies, liquidity event might not be as relevant (since they’re already liquid public stocks), but for any convertible securities or debt, there may be clauses for change-of-control events.

Options and Warrants: Sweeteners and Incentives

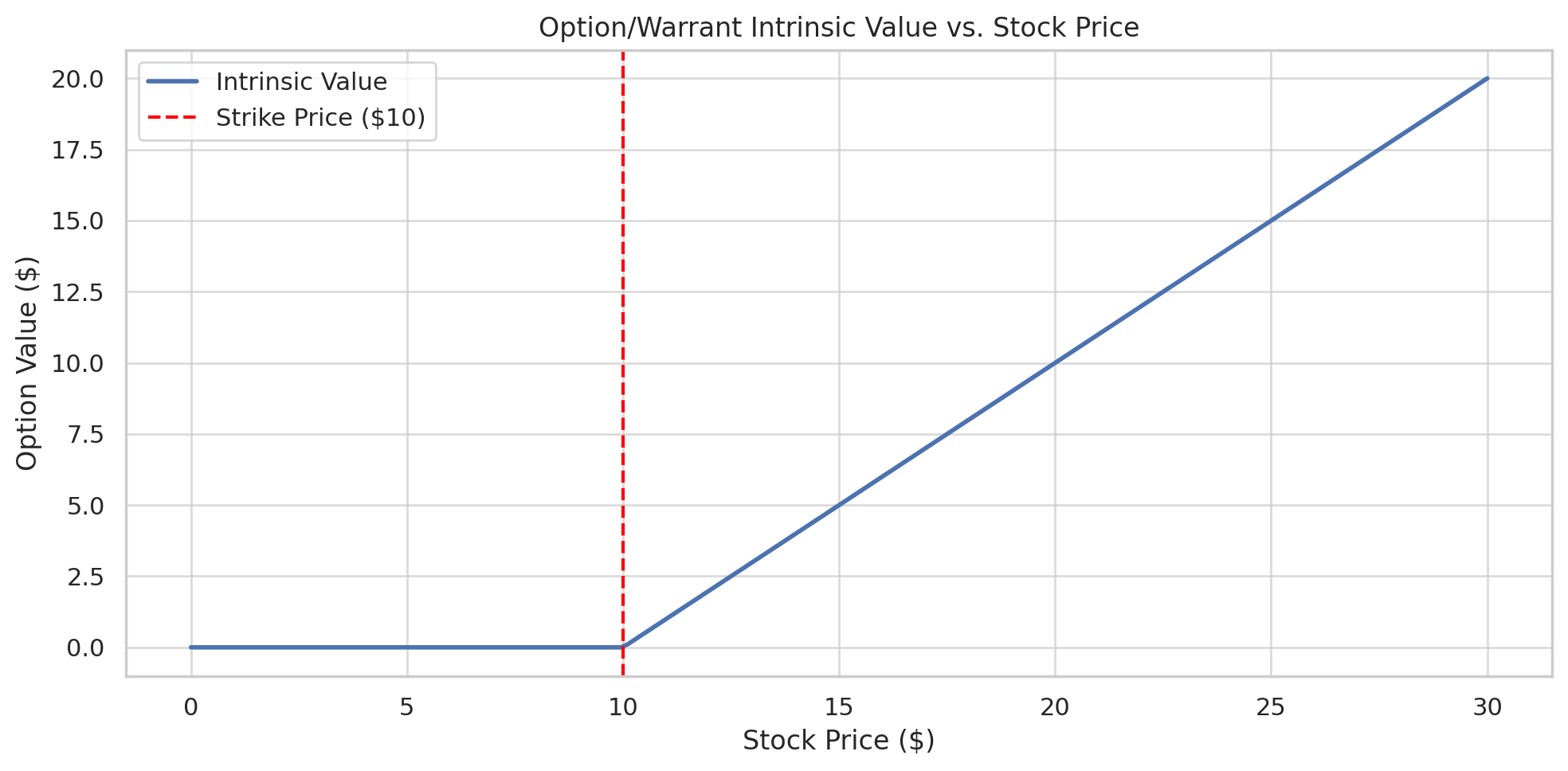

Equity options and warrants are both contracts that give someone the right to buy stock at a fixed price in the future, but they are used in different contexts:

Stock options typically refer to employee stock options – a form of compensation. Companies (especially startups) grant options to employees, advisors, etc., to incentivize and reward them. A stock option gives the holder the right to purchase a certain number of shares at a set “strike price” (often the market price at time of grant for public companies, or a fair market value for private companies) after some vesting period.

For example, a new scientist at a biotech startup might receive options for 10,000 shares at a strike price of $1 per share, vesting over 4 years. If the company later goes public or is acquired and the shares are worth $10 each, the scientist can exercise at $1 and then sell at $10, netting the $9 difference per share as profit. If the company fails and shares are $0, the options simply won’t be exercised (no obligation). Key points: options are usually not transferable, are intended for insiders (employees, sometimes board or advisors), and they have an expiration (often 10 years, or shorter if the person leaves the company).

There are different tax types (ISO vs NSO) but that’s detail beyond press release basics. Press releases might not frequently mention employee options, except perhaps in contexts like “the CEO was granted options” or total share counts (fully diluted shares including options, etc.).

Warrants are very similar in mechanism (a right to buy shares at a fixed price, called the exercise price or strike, within a certain timeframe), but are typically issued to investors or lenders as part of a financing deal rather than as employee comp. A warrant is often a “sweetener” in a deal. For example, a biotech might do a PIPE financing (private investment in public equity) where investors buy stock at $5/share and also receive warrants to buy additional shares at $7/share anytime in the next 5 years.

The warrant gives the investor upside if the stock exceeds $7 – it’s like a bonus for taking the risk now. Warrants are common in:

Venture debt deals

Lenders or venture debt funds often ask for a small equity kicker in the form of warrants. E.g. a lender gives a $10M loan and gets warrants for, say, shares equal to 0.5% of the company at some nominal price. This way if the company becomes a big success, the lender can exercise and get equity upside.

Warrants are commensurate with the amount of inherent risk, often warrants go unexercised given many startups fail, but the ‘diamond in the rough’ will bring outsized returns to the lender that make up for losses on others.

Public biotech offerings

It’s quite common for small-cap biotechs to issue units consisting of shares + warrants to entice investors. For instance (cabalettabio.com), Cabaletta Bio’s June 2025 public offering consisted of 39.2 million common shares sold together with 39.2 million warrants (one warrant per share) with an exercise price of $2.50 (warrant life ~15 months). The combined price was $2.00 for a share + warrant unit, effectively letting investors potentially double their shares at $2.50 if the stock rises above that.

This structure can make an offering more attractive if investors are cautious – the warrant is a bit of a sweetener for future upside. Another example: Xilio Therapeutics in 2023 did a financing where in addition to shares, investors got Series B and Series C warrants that could bring in additional cash if exercised by 2026.

The press release noted total gross proceeds could reach $150M if those warrants are exercised (ir.xiliotx.com), highlighting how warrants can be structured to provide follow-on funding.

Differences between options and warrants

While functionally similar (right to buy stock at a set price), the key differences are:

Who gets them

Options are typically issued to employees (or sometimes service providers) as part of an option pool for compensation. Warrants are issued to investors or partners as part of a deal (financing or sometimes a partnership deal).

Issuance and shares

When an employee option is exercised, usually the company issues new shares (there is typically an option pool reserve of common stock). Warrants when exercised also typically result in the company issuing new shares (often common stock or sometimes preferred if specified). Both cause dilution to existing shareholders when exercised. In financial statements, companies will often report a “fully diluted” share count assuming all options and warrants exercised.

Trading

Employee stock options cannot be sold or transferred (they either are exercised by the employee or expire). Warrants, on the other hand, can sometimes be detached and traded separately. For example, those warrants from the Cabaletta Bio offering likely trade on Nasdaq as well (in some cases) or can be transferred, depending on terms. They’re more like a security on their own. In private company context, warrants are usually transferable (subject to agreement) whereas options are not.

Term and vesting

Options usually have vesting schedules (you earn the right to exercise them over time as you stay with the company). Warrants given to investors generally vest immediately upon the deal (the investor paid for it as part of deal terms) and often have a longer window (commonly 5 to 10 years) before expiration.

Purpose

Options are to align employees with company success (incentive comp). Warrants are to entice investment or deals by giving external parties some equity upside. “Employees are given options as an incentive… whereas warrants are issued to a lender or investor as part of a transaction to sweeten the deal.

You might see something like “Company X enters loan agreement for $20M with warrants issued to the lender” – meaning the lender not only will get interest on the loan, but also got warrants (perhaps for some % of stock at a set price). This is a flag that the lender is taking on risk and wants equity upside.

Or in financing announcements: “$10 million raised through sale of common stock and warrants” – meaning investors bought units of stock + warrant. The details often include the warrant exercise price and term. (E.g. “each warrant is immediately exercisable at $Y per share and will expire in 5 years”).

If all those warrants eventually get exercised (which only happens if the share price goes above the exercise price), the company will receive additional cash and the investors will get additional shares.

In an IPO registration, you might see mention of outstanding options and warrants in the cap table.

For a biotech professional, the key thing to know is: Options and warrants represent potential future dilution (more shares could be created if these are exercised) and they give the holder a right to buy stock at a fixed price.

They’re generally positive signals in that someone sees potential upside (they only have value if the stock goes up), but they also overhang the stock (investors know more shares may hit the market if the price rises enough).

Real example – venture debt with warrants

In 2022, BridgeBio had a financing agreement with a creditor (as referenced in 2025 when they refinanced). Such agreements often contain warrants. Although their PR didn’t detail the original warrants, it emphasized that by refinancing with convertible notes, they were reducing interest and eliminating amortization payments, likely at the cost of giving new investors conversion rights (investor.bridgebio.com). Many other biotech loans (e.g., those from Silicon Valley Bank to startups) include small warrant coverage (e.g. “warrants equal to 2% of the loan amount” in shares).

Real example – public offering with warrants

The Cabaletta Bio offering we discussed: The company in June 2025 sold shares at $2.00 with an accompanying warrant per share at $2.50 exercise price (cabalettabio.com). That means anyone who bought the unit at $2.00 got a share plus a warrant that, if exercised, would cost $2.50 to get another share. The warrant was short-term (15 months).

Essentially, if Cabaletta’s stock goes well above $2.50 before September 2026, those warrants get exercised (investors pay $2.50 each to the company, the company thus raises up to an additional ~$125M, and the investors get more shares).

If the stock stays below $2.50, the warrants expire worthless in 2026. Press releases often mention the potential additional proceeds from warrant exercise (e.g., “if fully exercised, the warrants could result in an additional $X million proceeds” (ir.immunitybio.com). This signals to readers the best-case scenario of the financing (company could get more cash later) but it’s not guaranteed unless the stock performs.

To summarize options vs warrants in one line: Stock options are typically internal incentives for employees to buy stock at a set price in future, while warrants are deal sweeteners for investors/lenders giving them the right to buy stock at a set price. Both are contracts for potential future stock purchases. Both can create dilution if exercised.

Stock options give employees the right to buy shares at a set price (strike price) after a vesting period… Stock warrants are an agreement between two parties that gives one party (often an investor or lender) the right to buy the other party’s stock at a set price over a specified period of time. The main difference is simply the context/purpose (and that warrants usually have no vesting – they’re active immediately, and can sometimes be traded).

Reading Press Releases: Putting It All Together

When you read pharma/biotech deal press releases, you’ll now recognize these terms and understand their implications:

“Convertible Senior Notes” – This indicates a debt instrument (notes) that is senior (high priority claim) and convertible (can turn into equity). For example, “Company X announces $50M of 5-year senior convertible notes”. This means Company X is borrowing $50M; these notes rank at the top of the capital stack (often unsecured but senior); and investors have the option to convert into stock under certain conditions (often if the stock trades above a certain price or at maturity).

The press release will often specify the conversion price or formula, the interest rate, and any special clauses (e.g. forced conversion or redemption on a liquidity event). What it means in practice: Company X got $50M cash now, will pay interest (say 4-5% annually) – often interest might even be “paid-in-kind” (added to the balance instead of cash, as in Biofrontera’s note bearing 10% PIK interest).

If the stock performs well, investors might convert to equity (so the company would then not need to repay cash but would dilute shareholders). If not, the company owes the cash back at maturity. As a reader, note if the conversion price is much higher than current stock – it indicates investors believe in upside (or at least wanted equity sweetener). Also note any covenants mentioned (Biofrontera’s PR explicitly listed restrictive covenants in the note deal – basically telling you the company is now limited in certain actions until it repays that debt).

“Senior Secured Term Loan with Covenants”

If a company announces a loan, “senior secured” tells you it’s backed by collateral (often the company’s IP or other assets), and the lender is first in line on those assets. Covenants will likely include things like minimum cash, etc. In practice: the company got cash but must abide by those covenants.

Check if the PR or subsequent SEC filings mention needing to raise cash by a date or maintain X months of runway – those are covenant clues. If a PR says “amended its credit facility to modify covenants”, that means the company negotiated with the bank to loosen/tighten some rules, often in response to changing financial projections.

“Equity financing with liquidation preference”

In a venture funding announcement (for a private biotech), you might see “Series B Preferred financing of $20M”. The details might not be in the PR, but you can infer that Series B investors got preferred stock likely with a 1× liquidation preference (almost always true unless stated otherwise). Some PRs or blogs may note if it was participating or not, but usually one assumes non-participating 1× unless news says an investor got unusually favorable terms.

Practically: If you later read the S-1 IPO filing, you might find all those terms spelled out (e.g. “Series B has a liquidation preference of 1× the $20M invested, non-participating, converting to common at IPO”). As a non-finance person, just know that means those investors have downside protection – they’ll get that $20M back first if the company sells for anything above $20M, which could affect how much common shareholders (like employees) would get.

“Milestone-based warrant or option”

Sometimes a deal (especially licensing deals) might include an “option” in a different sense: e.g. Big Pharma Y gives Biotech Z $50M upfront, and Big Pharma Y gets an option to license a second program by paying $X more later – that is more of a business development option, not a stock option. Don’t confuse the two. In press releases, a phrase like “option to acquire” or “option to license” refers to a right to execute a business transaction in future. Whereas “stock option” will usually be in context of equity grants or plans.

Warrants will always refer to the securities described above (right to buy stock). For example, “Company Y issued the investor 1 million warrants at $10 strike price as part of the deal” – as a reader you’d interpret that as: the investor can later pay $10M to get 1 million shares (thus likely they expect shares to be worth more than $10 to bother).

“Liquidity event” mentions

If a press release or investor presentation mentions “we anticipate a liquidity event in 18–24 months for our shareholders”, they are talking about an IPO or sale. In the context of an investor exit, it’s positive (they plan to get investors liquid). In the context of debt or preferred stock, look for phrases like “upon a change of control, X will happen”.

Change of control = acquisition (one type of liquidity event). It might trigger conversion of notes, or a requirement to pay off debt (many debt agreements force the company to pay them off if an acquisition occurs – no acquirer wants to take on your high-yield venture debt; they’d rather pay it off).

So as a practical matter, a company with a lot of debt (especially with covenants or change-of-control provisions) may have less flexibility to entertain an acquisition unless the buyer is ready to also clear that debt.

To wrap up, deal press releases are essentially translating complex financial agreements into public information. Now that you know these basics, you can decode them:

- Senior vs. junior: Who gets paid first.

- Secured vs. unsecured: Whether specific assets back the debt.

- Covenants: What the company can/can’t do while the debt is outstanding (look for words like “subject to customary covenants” or “must maintain at least $X in cash”).

- Liquidation preference: Preferred equity’s special right to money back first in a sale (not usually spelled out in a PR, but always in the financing terms behind the scenes).

- Liquidity event: A sale/IPO that lets investors cash out (the context will tell you if it’s about investors exiting or a triggering event for an instrument).

- Options and warrants: Extra equity rights – if mentioned, they tell you about potential dilution and the confidence/terms of stakeholders (e.g. a low strike price warrant given to lenders means those lenders wanted a likely in-the-money upside; a high strike price means the company maybe negotiated better).

Armed with this understanding, you can read something like: “BioTech ABC announces a $30M Series C financing led by PharmaVentures. The Series C Preferred Stock carries a 1x non-participating liquidation preference and customary anti-dilution protections. Concurrently, ABC secured a $10M venture debt facility from XYZ Bank, which includes warrants for XYZ to purchase shares equal to 2% of ABC’s common stock.” and realize that:

- PharmaVentures gets preferred shares that will get their money back before common if ABC sells, but they won’t double dip (non-participating).

- The investors likely negotiated anti-dilution (if ABC raises a down-round later, they get some adjustment).

- XYZ Bank loaned $10M and to sweeten that, they got warrants for ~2% of the company’s stock (likely at the current valuation). So if ABC becomes a unicorn, XYZ Bank can exercise those cheaply and enjoy equity upside.

- Also, ABC now likely has covenants from that venture debt (perhaps needing to keep enough cash, etc., though the PR didn’t detail them).

- If ABC gets acquired, Series C investors get at least their $30M first, and the XYZ Bank loan probably must be repaid (and warrants might either be exercised or cashed out for the spread).

By understanding senior notes, covenants, preferences, liquidity events, options, and warrants, you’ll have a clearer lens on what deal terms mean for the company’s financial health and for stakeholder outcomes. You’ll see who has leverage and protection in the deal. Ultimately, this helps in evaluating how favorable or risky a deal is for the company and its various investors – critical insight whether you’re a biotech founder, employee, or just following industry news.

Member discussion