Biotech Venture Capital’s Hard Reset

The global biotech venture capital boom of the late 2010s has decisively given way to a sobering downturn. After a decade of exuberance, investment levels in mid-2025 have retreated to where they stood in the early 2010s (biospace.com). The industry is emerging from a classic cycle of boom and bust, grappling with leaner funding, fewer startups and a murky exit environment. Yet amidst the caution, optimists see a silver lining: a period of capital discipline that could ultimately foster more sustainable innovation. This report surveys the current state of biotech venture financing worldwide – from shrinking Series A activity to shifting investor behavior and the scramble for alternative exits – and asks whether today’s hardship might be paving the way for a healthier cycle ahead.

From Feast to Famine in Funding

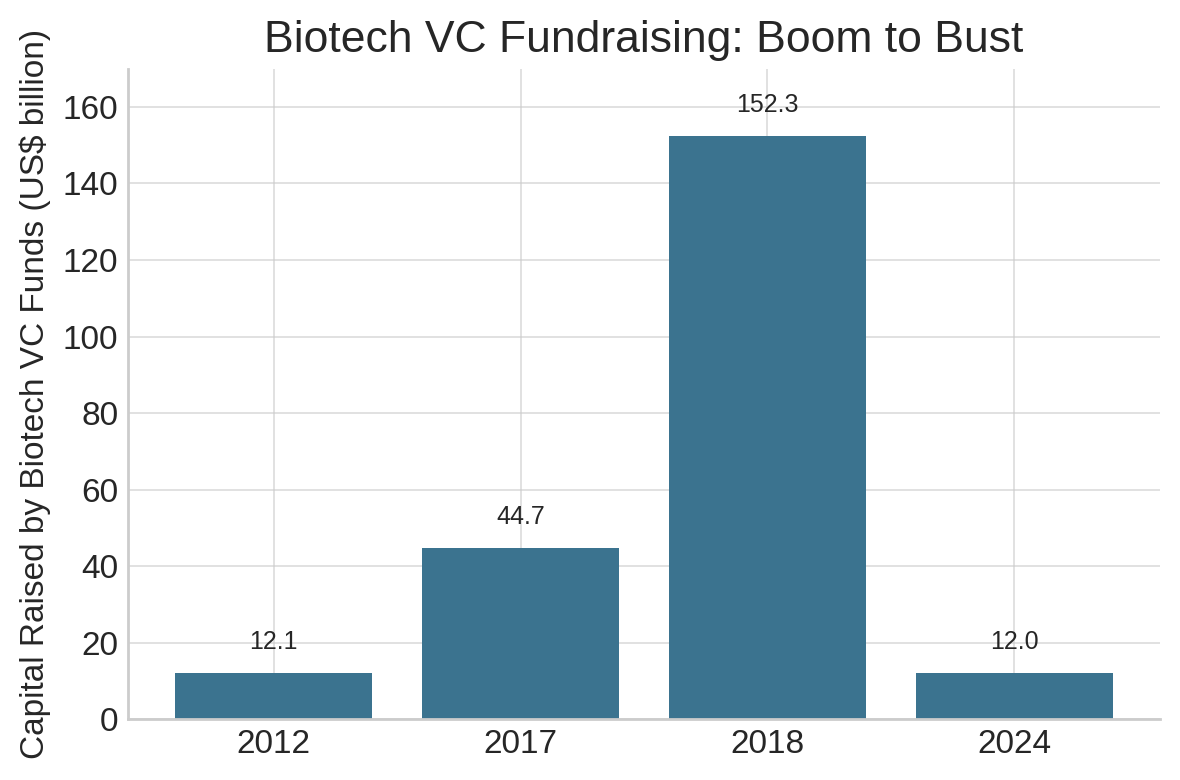

Few sectors exemplified the venture capital frenzy of the past decade better than biotechnology. In the span of ten years, biotech VC financing went from modest beginnings to unprecedented heights – and back again. PitchBook data show that in 2012, dedicated biotech venture funds raised about $12 billion, a baseline for the cycle that followed (biospace.com). Investor enthusiasm then surged dramatically. By 2017, annual biotech VC fundraising had quadrupled to $44.7 billion (biospace.com). An “explosive expansion” ensued between 2018 and 2021, marked by record capital flooding into the field (biospace.com). Fundraising peaked at an astonishing $152 billion in 2018 (biospace.com) – a figure reflecting global investor zeal for life-sciences startups, including a wave of new funds and cross-border capital.

That era of plenty has definitively ended. As of 2024, biotech venture fundraising collapsed back to roughly $12 billion – essentially the same level as in 2012 (biospace.com). The number of new VC funds focused on biotech also plunged to only 46 worldwide in 2024, down from over 300 funds launched at the 2021 peak (biospace.com). Early 2025 brought little relief, with just four biotech VC funds closing in the first quarter (biospace.com). The reasons for this dramatic pullback are manifold. Rising interest rates and a higher cost of capital have made investors warier of long-horizon bets (biospace.com). The post-pandemic market rout for biotech equities has dampened enthusiasm, and the once-frenetic pace of startup formation has slowed to a crawl. Venture firms themselves have become far more selective in deploying their capital, reacting to scarce exit opportunities and a reset of valuations.

Leaner Series A Rounds and Fewer Startups

Nowhere is the retrenchment more evident than in early-stage activity. The pace of new biotech startup formation is down nearly 70% from its peak in early 2021 (stifel.com, stifel.com). In the first quarter of 2025, the number of biotech companies securing their first venture financing hit the lowest level in at least a decadestifel.comstifel.com. During the boom, virtually every week brought news of another ambitious biotech launching with an outsized Series A round; by contrast, today’s startups are few and far between. When demand for biotech equity was frothy, over 170 biotech startups received first financings in a single quarter (Q1 2021) (stifel.com). Now, with investors more cautious, that supply of new ventures has dwindled dramatically. This contraction, while painful for entrepreneurs, could carry “benefits of scarcity” by reducing duplication and competition for talent (stifel.com, stifel.com). Seasoned venture builders note that great companies are often born in downturns when only the strongest ideas attract funding – as seen in past biotech bear markets that gave rise to successes like Alnylam and Nimbusstifel.com.

Importantly, “leaner” does not necessarily mean tiny financing amounts – rather, it implies capital deployed with more discipline. A few novel companies still manage to raise large rounds, but these are now the exception reserved for especially hot fields or well-validated science. For example, late 2024 saw Maze Therapeutics secure $115 million in funding, a hefty raise co-led by Frazier Life Sciences and Deep Track Capital (biospace.com). Similarly, ArtBio (a startup on BioSpace’s list of top NextGen companies for 2025) pulled in a $90 million Series A round in December 2023, backed by prominent biotech VC firm Third Rock Ventures (biospace.com). These deals show that capital is still available for companies with compelling platforms, but the bar is significantly higher. In general, round sizes and valuations have come down from the heady days of 2018–21. Investors are writing checks with an expectation that companies do more with less, trimming excess and focusing on achievable milestones. Indeed, one analysis found that the median time between funding rounds has increased, reflecting a “cautious yet discerning investment approach” where VCs wait for mature data before re-upping (fiercebiotech.com, fiercebiotech.com). The upshot is that Series A financings in 2025 tend to fund narrower, more efficiency-driven plans, in contrast to the sprawling “raise money now, figure it out later” ethos that prevailed at the peak of the boom.

Globally, the downturn in venture funding is broad-based. In the United States – by far the largest biotech VC market – venture investment in biopharma startups fell to about $29.9 billion in 2023, down from $36.7 billion in 2022 (fiercebiotech.com). This marked a significant correction from the pandemic-fueled heights earlier in the decade. Europe’s biotech scene has likewise suffered: investment on the continent has dropped sharply in recent years with no clear sign of recovery (pitchbook.com). Meanwhile, geopolitical rifts have cooled the flow of capital into China’s once-booming biotech sector. U.S. venture firms, which had been active backers of Chinese biotechs in the late 2010s, largely pulled back after 2020. In fact, U.S. VCs participated in only 29 funding rounds for Chinese startups in the first five months of 2024, a tiny trickle worth less than one-tenth of the previous year’s dollar volume (spglobal.com, spglobal.com). Tighter investment restrictions and a harsher market climate have made Chinese biotechs more reliant on domestic funds and partnerships. All told, the era when capital gushed freely across geographies has given way to one of local constraints and cautious deal-making.

Specialists Double Down, Generalists Pull Back

For the select venture firms that specialize in life sciences, the current reset is a moment to double down on core strengths – albeit with moderated ambitions. Specialist biotech VCs are continuing to do what they do best, but with more measured capital deployment (biospace.com). Flagship Pioneering, for instance, remains focused on its trademark model of company creation (incubating new startups from scratch), but it is pacing its investments carefully rather than flooding each venture with cash upfront (biospace.com). Other experienced players are similarly recalibrating. Canaan Partners armed itself with a $1.12 billion fund in 2023 and is now channeling that capital into early-stage opportunities with capital-efficient development paths (biospace.com).

In practice, this means backing startups that have clearer product trajectories or leaner R&D designs, so they can reach value inflection points without requiring astronomical sums. F-Prime Capital, which raised a $500 million fund in 2023, has tilted its strategy toward platform technologies offering multiple shots on goal (for example, drug discovery platforms that can generate several therapeutic candidates) (biospace.com). The idea is to hedge bets by investing in versatile biotech platforms that could spawn many products – a prudent approach when each individual program faces scientific uncertainty.

These life science specialists can take solace in a strong long-term track record. Biotech-focused VC funds have outperformed their non-biotech peers across many vintage years, often delivering top-quartile returns for investors (biospace.com). Firms such as RA Capital, Foresite Capital and Perceptive Advisors earned renown during the boom for savvy timing and lucrative exits, and their domain expertise positions them to navigate the downturn (biospace.com).

Deep scientific knowledge is now, more than ever, a prerequisite for success in biotech investing. As PitchBook analysts note, VCs in this sector must have the expertise to “guide decision-making” with scientific diligence (biospace.com). Funds like Atlas Venture, 5AM Ventures and of course Flagship Pioneering exemplify this approach of hands-on, science-driven venture building (biospace.com). In lean times, that diligence helps avoid backing flimsy science or overhyping unproven modalities. Specialist investors appear willing to roll up their sleeves and work closely with startups to de-risk projects step by step.

By contrast, many generalist venture firms have scaled back their biotech exposure, licking wounds from the bust. Crossover funds and diversified tech investors that dabbled in biotech during the bull market – enticed by high valuations and IPO pops – largely retreated when the market soured. However, a few prominent generalist VCs that maintain dedicated life science teams are still in the game and arguably in a better position now than during the crowded boom. PitchBook points out that firms like Dimensions and Lux Capital may thrive in this environment with less competition and better valuations (biospace.com).

Lux Capital, for example, closed a $1.15 billion fund in 2023, part of which targets health and biotech ventures (biospace.com). In today’s climate, Lux and peers can cherry-pick biotech deals without facing as many bidding wars from momentum-chasing outsiders. Lower entry prices for equity stakes make the risk-reward calculus more attractive, provided one has patience for a longer exit timeline. These generalist investors, though fewer in number now, could help fill financing gaps for startups that fall outside the narrower theses of specialist funds – especially in interdisciplinary areas like biotech-adjacent AI or engineering-heavy life-science tools.

Internationally, the specialist-generalist dynamic is also playing out. In Europe, a handful of sector-focused funds (e.g. Sofinnova, SR One’s European arm) continue to deploy capital, but U.S. pullback has left some funding void. In emerging biotech hubs, government-affiliated and corporate venture players have become relatively more important as global VCs cool off. One notable trend is the rise of corporate venture investment from big pharmaceutical companies stepping in to support startups, effectively partially substituting for absent crossover investors. This reflects an industry-wide refocusing on core expertise: those with true conviction and strategic interest in biotech remain active, while tourists have exited. The result is a smaller, more specialized pool of venture investors – which, as some suggest, might lead to more rigorous oversight and rational portfolios.

Exit Routes: M&A in the Spotlight

If raising capital is harder in 2025, cashing out is harder still. The traditional exit pathway for venture-backed biotechs – the IPO – has all but closed. In 2021, at the peak of the frenzy, more than 100 biotech companies went public, collectively raising nearly $15 billion in IPO proceeds (biopharmadive.com). That year set a record, with 104 biotech IPOs on U.S. exchanges (pharmasalmanac.com), flooding the market with fresh listings. The subsequent downturn has been brutal. There were only 21 biotech IPOs in 2022 (bdo.com), and while 2023 saw a modest uptick with 55 IPOs worldwide (fiercebiotech.com), the volume remained a fraction of the boom-time levels.

So far in 2025, the window for new offerings remains essentially shut – “IPOs out of the question,” as PitchBook dryly put it (biospace.com). Public-market investors have little appetite for early-stage or unprofitable biotech stories amid a broader risk-off mood. The few companies that have ventured public recently often did so at slashed valuations or via quiet uplistings, yielding meager returns to earlier backers. This dearth of IPOs poses a serious challenge for venture capitalists, who count on successful exits to recycle capital back into new investments. With the timeline to liquidity extended, VC firms must reserve more cash to support their portfolio companies or else face having promising startups run out of money.

In the absence of IPOs, mergers and acquisitions have become the primary hope for exits, but here too activity has been mixed. Big pharmaceutical companies, sitting on strong balance sheets, have always been logical acquirers of biotech innovation – and indeed, some have started bargain-hunting among beaten-down targets. The first quarter of 2025 was middling for biotech M&A, but the pace quickened in the second quarter with a flurry of deals announced in late May and early June (biospace.com).

Notably, Sanofi made headlines by agreeing to acquire U.S.-based Blueprint Medicines for $9.5 billion in early June (biospace.com). That deal, focusing on Blueprint’s rare disease drugs, signaled that large buyers are willing to pay up for attractive assets even in a risk-averse market. It was quickly followed by a substantial collaboration (with an option to acquire) between Bristol Myers Squibb and BioNTech, involving over $11 billion in potential value for a novel cancer therapy (biospace.com). And in the biggest splash of Q1, Johnson & Johnson inked a $14.6 billion acquisition of Intra-Cellular Therapies, a mid-cap biotech with a flagship psychiatry drug (biospace.com). These big-ticket deals show pharma’s continued strategic need to replenish pipelines, especially as valuations of target companies have come down from their peaks.

Equally telling has been a series of “tuck-in” acquisitions of smaller biotechs – often companies whose stock prices were languishing. Jefferies analysts noted that by late May, at least three small-cap biotechs had quietly been snapped up: Vigil Neuroscience (acquired by Sanofi), Regulus Therapeutics (bought by Novartis) and Inozyme Pharma (bought by BioMarin) (biospace.com). None of these targets were household names; they were relatively obscure players with niche programs. Their takeovers, largely absent the fanfare that accompanies larger mergers, underscore the pressures facing sub-$500 million market cap biotechs. By early 2025, fully 22% of publicly-traded biotech companies were valued at less than the cash on their balance sheet – roughly 80 companies trading “under cash,” the highest share in at least nine years (biospace.com).

Many of these firms have promising science but have been punished by investor flight, making them essentially cheaper to buy on the stock market than to fund as private entities. In such cases, a takeover can be a win-win: pharma acquirers pick up assets at a discount, while the biotech’s management and VC owners salvage some value (often a premium to the depressed share price) for shareholders. “If valuations remain pressured, we predict the number of small-cap M&A deals could rise in the next 6–12 months,” Jefferies wrote, noting that as cash runways dwindle, more boards will conclude that selling is preferable to dilutive financing or bankruptcy (biospace.com).

Recent Notable Biotech M&A (Jan–May 2025):

| Acquirer | Target (Sector) | Price | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson & Johnson | Intra-Cellular Therapies (CNS) – public company | $14.6 billionbiospace.com | Q1 2025biospace.com |

| Sanofi | Blueprint Medicines (Rare diseases) – public company | $9.5 billionbiospace.com | June 2025biospace.com |

| Sanofi | Vigil Neuroscience (Neuroscience) – small-cap | Undisclosed (all-cash)biospace.com | May 2025biospace.com |

| Novartis | Regulus Therapeutics (Genetics) – micro-cap | Undisclosed (all-cash)biospace.com | May 2025biospace.com |

| BioMarin | Inozyme Pharma (Rare diseases) – small-cap | Undisclosed (all-cash)biospace.com | May 2025biospace.com |

Sources: Company announcements and PitchBook/BioSpace reports.

The uptick in acquisitions has provided a glimmer of hope in an otherwise gloomy exit market. Still, the overall industry picture remains one of exit challenges and delayed liquidity. Even as M&A picks up, it cannot fully compensate for the near-absence of IPOs. The total value of biotech exits (IPOs plus acquisitions) in 2023 was just $18.3 billion, spread across under a hundred transactions (fiercebiotech.com) – a far cry from the hundreds of billions venture investors poured in during the prior decade. Venture capital funds are consequently holding companies longer and deferring returns to their own backers (the LPs). This dynamic threatens to create a funding logjam: without exits, VC firms struggle to raise fresh funds, which in turn constrains new investments – a vicious cycle often referred to as the biotech “doom loop.”

In public markets, biotech indices remain well below their peaks, and many crossover investors (funds that invest in both private and public biotech) are nursing heavy losses, further reducing the crossover money available for late-stage private rounds. All these factors force venture investors to prepare to hang on for longer (biospace.com). Those with capital are channeling more into supporting existing portfolio companies through bridge financings and extensions, hoping to keep them afloat until either the IPO window reopens or an acquirer emerges. Startups, for their part, are exploring creative survival strategies – from licensing deals to reverse mergers with cash-rich shells – to buy time. It is a grinding, hold-your-breath period for everyone involved.

The Discipline Dividend?

If there is a silver lining to biotech’s venture capital reset, it is the possibility that “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” The current capital scarcity, while painful, may impose a healthy discipline that was often lacking during the go-go years. “Historical patterns suggest that periods of capital constraint often precede cycles of disciplined, high-quality company formation,” analysts at PitchBook observed, noting that today’s caution “may be establishing a more sustainable foundation for the next phase of biotech innovation” (biospace.com).

In plainer terms, the hope is that with easy money off the table, the biotech ecosystem will refocus on quality over quantity. Fewer startups are being launched, but those that do get funded tend to have more robust science, clearer product hypotheses and management teams prepared to operate frugally. Ventures are now conceived with the understanding that follow-on capital must be earned, not assumed. This stands in stark contrast to the peak boom mentality, when abundant cash allowed some companies to IPO or raise giant rounds on hype and promise alone.

Investors also highlight a potential “benefits of scarcity” effect: with less overcrowding, the average health of the herd may improve (stifel.com, stifel.com). In recent commentary, Atlas Venture’s Bruce Booth (a veteran biotech VC) argued that the winnowing of venture-backed biotechs is ultimately positive for the sector’s equilibrium (stifel.com, stifel.com). During the boom, too many similar startups chased the same targets, and talent was stretched thin across dozens of new enterprises.

Now, with far fewer new entrants, the startups that remain can hire more easily and face less “hyper-competition for resources” (stifel.com). Scarcity also encourages focus: companies and VCs concentrate on only the most promising programs, rather than scattering efforts across speculative moonshots. As one industry saying goes, great biotech companies are often born in bear markets – when the noise subsides and truly innovative ideas can emerge from the rubble. Historical anecdotes back this up: Alnylam, a pioneer of RNAi therapeutics, was founded in the lean days of 2002; likewise, landmark startups like Nimbus and Kymera sprung from the doldrums of 2009 and 2016 respectively (stifel.com). Necessity can be the mother of invention.

All that said, the road ahead for biotech venture funding is not without bumps. The macroeconomic climate remains uncertain, and a sustained downturn could still drive away more investors or strand good science unfunded. Biotech is nothing if not cyclical, prone to oscillations of sentiment. A broader market recovery – or a breakthrough drug approval that reignites excitement – could thaw the funding freeze faster than expected. Indeed, areas like obesity and Alzheimer’s have recently delivered clinical successes that stirred investor interest, suggesting not all enthusiasm is lost. Additionally, large pharmaceutical companies have signaled they will continue to scout for external innovation, which provides a backstop of demand. In mid-2025, for instance, even as startups tighten belts, pharma R&D budgets are robust and partnerships are being struck at a healthy clip.

In the meantime, however, both entrepreneurs and venture capitalists appear to be embracing a new mantra: capital efficiency and patience. Gone are the days of blitzscaling in biotech; the mantra now is to “execute milestones on a shoestring and earn the next round.” This disciplined approach may slow the pace of progress in the short term – fewer programs started, and more incremental advances – but it could also mean that the companies which do make it through are fundamentally stronger. If the PitchBook analysis is correct, today’s recalibration will pave the way for “the next phase of biotech innovation and investment” on firmer footing (biospace.com). In other words, the hope is that a chastened, wiser biotech venture ecosystem will emerge from this cycle: one that still fuels breakthrough medicines and technologies, but without the excesses of the last boom. For an industry defined by scientific risk, a dose of financial sobriety may indeed be just what the doctor ordered.

Member discussion