Biotech’s Glass Cage: The Overton Window, the Asymmetric Risk Trap, and the Limits of Scientific Imagination

It is not often that the bounds of acceptable discourse are described in terms of architecture. Yet the Overton Window—a tidy metaphor for the range of ideas considered palatable in public life—has quietly shaped not only politics, but science, finance, and the technological imagination. What is permissible to say, to fund, to build, and to believe is defined not by truth but by social temperature. Within this invisible window lies safety, credibility, and the warm embrace of consensus. Outside it? Mockery, marginalization, and most fatally of all—funding rejection.

For biotech, a discipline supposedly built on disruption, the Overton Window functions not as a helpful constraint but as a glass cage. It protects the status quo while punishing intellectual deviance. This is a field that claims to revolutionize life itself, yet is often as risk-averse as a central banker with a hangover.

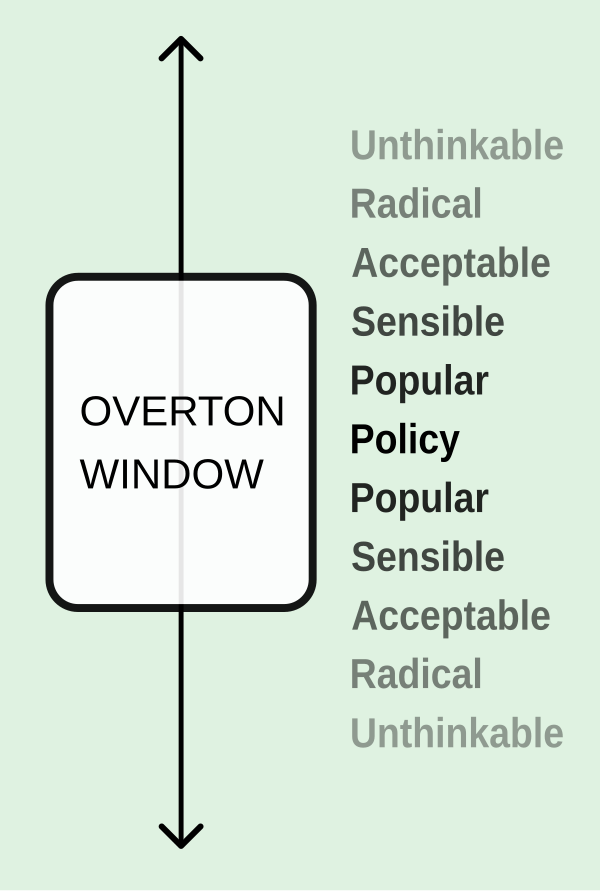

Let us sketch the window as it applies to science.

Visualizing the Overton Window in Biotech

Imagine a spectrum of ideas:

In this model, ideas do not exist in isolation. Their legitimacy depends on where they fall on this continuum. “Eradicating aging” may sit today between Radical and Acceptable. “Editing embryos for intelligence” remains firmly in the Unthinkable zone, except perhaps at dinner parties in Palo Alto. “Developing a fifth checkpoint inhibitor” is squarely in Sensible territory, and is likely to attract both funding and FDA meetings within the fiscal quarter.

The real innovation does not lie in Sensible. It lies just outside it. But to reach that space—where breakthroughs emerge—scientists and entrepreneurs must navigate the treacherous ground of reputation risk, funding risk, and institutional inertia. The Window may shift over time, but it rarely moves ahead of culture. Science does not lead so much as it tiptoes behind public sentiment and the capital markets that reflect it.

This is the irony. The most transformative ideas—mRNA vaccines, gene editing, psychedelics for psychiatric care—were all once outside the window. Their eventual acceptance did not come from overwhelming evidence, but from moments of rupture: a pandemic, a political shift, a billionaire with a god complex.

The Polite Rejection of Dangerous Ideas

The language of window-policing is subtle. No one says: “this idea is socially unacceptable.” Instead, reviewers mutter that it’s “too early.” Investors complain it lacks “commercial clarity.” Journals will say it’s “methodologically unsound.” This is how the Overton Window enforces respectability: not through censorship, but through polite exclusion.

Consider the scientist who proposes a novel method of cellular reprogramming to reverse aging. Even if the preliminary data are promising, grant reviewers may balk. There’s no precedence, they say. Reviewers are skeptical. Pilot funding is refused. Publishable results never materialize—not because the idea was wrong, but because the ecosystem never permitted it to be tested.

This isn’t just theoretical. Katalin Karikó, co-inventor of mRNA vaccine technology, spent decades being denied funding and academic promotion. Her research was, quite literally, outside the window—until a global pandemic smashed the pane and rewrote the rules.

In biotech, science is shaped by what is fundable, and funding is shaped by what is acceptable. The causal arrow does not go from data to support—it goes from support to data.

The Asymmetric Risk Trap

Enter the second act of this quiet tragedy: the Asymmetric Risk Trap. This is the institutional pathology that arises when the downside of pursuing controversial ideas is personal and immediate, while the upside is collective, delayed, and often captured by others.

For the individual scientist or fund manager, proposing something outside the window is reputationally dangerous. Fail, and you’re a crank. Succeed, and at best you become a footnote to a movement you helped start. For those with steady careers, the rational choice is to keep one’s head down and work on what others already believe.

This is not cowardice. It is game theory. The payoff matrix is broken.

A simplified version of the trap might look like this:

| Success (Breakthrough) | Failure | |

|---|---|---|

| Within Window | Promotion, Funding, IPO | No penalty |

| Outside Window | Delayed recognition, others benefit | Career damage, ostracism |

In other words: the expected value of outside-the-window ideas is high in the long run, but catastrophically low in the short run. This skews the entire industry toward minor modifications, safe bets, and buzzwords that would survive a focus group of actuaries.

And yet, biology does not obey the window. Nor does disease. Nor does discovery.

Taleb, Fat Tails, and the Blind Spot of Biotech

If the Overton Window defines what is socially acceptable, Taleb’s epistemological warning defines what is statistically ignored. In The Black Swan, Nassim Nicholas Taleb makes the case that rare, high-impact events—so-called “fat tails”—shape history more than averages ever will. But our models, institutions, and biases are built to ignore fat tails in favour of comforting regularity.

Biotech, paradoxically, is a fat-tailed domain run by thin-tailed logic. Venture capital demands five-year exits. Regulatory pathways demand precise endpoints. Payers demand cost-effectiveness ratios with confidence intervals.

But the most valuable medicines are almost never predictable. Consider monoclonal antibodies. Once dismissed as impractical, they now comprise one of the largest drug classes in history. The real story of biotech is one of improbable ideas made inevitable by persistence.

Taleb would argue—correctly—that we have built a system that is anti-fragile to small errors but brittle to paradigm shifts. The window keeps us safe from noise but deaf to signal.

The Window Moves, But Rarely on Purpose

Overton himself noted that the window can shift. Ideas that were once unthinkable become common sense. But the shift is rarely driven by argument. More often, it is the result of crisis (see: COVID), celebrity endorsement (see: psychedelics), or cultural drift (see: AI).

Science, left to its own devices, rarely widens the window. Institutions are designed to protect consensus, not challenge it. What moves the window is not better data, but a better story—or a worse catastrophe.

To wit: anti-aging research remained a punchline until the likes of Calico, Altos, and Hevolution began funding it in earnest. The science didn’t change. The window did.

A Wider Frame

So where does that leave us?

The Overton Window in biotech is real. It defines the ideas that shape the next decade—and it excludes those that could shape the century. The Asymmetric Risk Trap ensures that the best minds avoid the riskiest questions. Taleb’s fat tails show us that we are most blind to the things that matter most. This is not a call for scientific anarchy. It is a call for institutional humility.

Biotech’s future does not lie within the current window. It lies just outside it—among the improbable, the unfundable, the strange. But to reach it, we must fix the architecture of risk. We must reward those who take long bets. We must treat failure not as a firing offence, but as the cost of radical exploration.

Until then, biotech will remain a cathedral of possibility surrounded by a fence of respectability.

The view is beautiful. But the window doesn’t open.

Member discussion