Comparative Regulatory Approaches to AI in Drug Development (as of July 2025)

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are rapidly transforming drug development and clinical trials. Medicines regulatory agencies worldwide have responded by issuing guidance, strategic plans, and holding stakeholder engagements to ensure AI is used safely and effectively in the development of new therapies. This report reviews how major agencies – the U.S. FDA, EMA (EU), UK MHRA, Swissmedic, Israel’s Ministry of Health, and Norway’s medicines agency – regulate AI as of mid-2025. We compare the depth and completeness of their AI frameworks, the timeliness of updates, and their engagement with industry and other stakeholders.

FDA (United States) – Draft Guidance and Active Engagement

Regulatory Guidance

The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) has developed a comprehensive draft guidance on AI in drug and biologic development. In January 2025, FDA released “Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Drug and Biological Products” (draft). This guidance provides detailed recommendations for industry on using AI/ML to generate data supporting drug safety, efficacy, and quality decisions. Notably, it addresses AI use across the entire product lifecycle – including nonclinical research, clinical trial design/analysis, manufacturing, and post-market surveillance. This makes FDA’s guidance very comprehensive in scope(fda.gov).

Depth and Content

FDA’s draft guidance emphasizes a risk-based approach to AI. It advises sponsors on ensuring AI models are validated and fit-for-purpose for their context of use, with greater regulatory scrutiny on AI tools that influence high-impact decisions (e.g. determining trial eligibility or supporting efficacy claims). The guidance was informed by FDA’s internal experience with over 500 AI-related submissions (2016–2023), indicating the agency has substantial practical insights. It also references principles of Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) and data integrity to maintain traceability, transparency, and bias mitigation in AI models (fda.gov).

Overall, FDA’s framework is highly detailed, covering technical considerations from data selection and model validation to performance monitoring and explainability. It even spans AI in manufacturing (GMP) and pharmacovigilance, mirroring the breadth of EMA’s later reflection paper.

Timeliness and Updates

FDA has been building this framework over several years. A public discussion paper on AI in drug development was published in mid-2023, followed by an open comment period that garnered 800+ comments. FDA also convened expert workshops (e.g. with Duke-Margolis Center in Dec 2022) and a public workshop in Aug 2024 to gather stakeholder input on AI best practices. These inputs fed into the 2025 draft guidance. FDA’s approach is current and forward-looking – the draft will likely be refined after public feedback and finalized, ensuring guidance stays up-to-date.

FDA also published a cross-center AI working plan in early 2024 (updated Feb 2025) to harmonize AI policy across its drug, biologic, and device centers. Internally, CDER formed an AI Council in 2024 to coordinate policy and training as AI use grows, including new areas like generative AI (fda.gov).

Stakeholder Engagement

FDA’s engagement has been extensive. In addition to publishing concept papers and seeking written comments, FDA actively involved industry, academia, and other experts through workshops. Notably, an FDA-Duke Margolis workshop in 2022 and a public workshop in 2024 allowed exchange on guiding principles for AI in drug development (fda.gov).

The agency’s transparent, consultative process reflects a high level of stakeholder involvement in shaping AI regulations. FDA also collaborates internationally (e.g. sharing GMLP principles with Health Canada and MHRA) to align on AI oversight. Overall, the FDA’s AI regulatory effort scores very high in depth and engagement, with a broad, up-to-date framework informed by significant external input.

European Medicines Agency (EMA) – Reflection Paper and Strategic Plan

Regulatory Guidance

The EMA has taken a multifaceted approach, centered on a broad Reflection Paper on the use of AI in the medicinal product lifecycle. This reflection paper – adopted by EMA’s human (CHMP) and veterinary (CVMP) committees in September 2024 – provides the Agency’s current views and considerations for using AI/ML at all stages of drug development: from drug discovery and non-clinical research, through clinical trials, manufacturing, to post-authorisation.

Published in final form in October 2024 after public consultation, it serves as high-level guidance to industry on how to deploy AI safely and effectively across each phase of a medicine’s lifecycle. EMA’s paper explicitly acknowledges both the opportunities of AI in accelerating R&D and the risks (e.g. data bias, “black-box” algorithms) that must be managed to protect patient safety and data integrity.

Depth and Content

The EMA reflection paper is comprehensive in coverage. It outlines key principles and expectations for AI use in:

Drug discovery (ensuring any AI-derived insights submitted in dossiers adhere to scientific standards):

Non-clinical studies (AI models that influence first-in-human trials or safety assessments should follow GLP and data integrity guidance)

Clinical trials (AI systems used in trials must comply with GCP; high-impact AI tools may require EMA qualification or protocol disclosure)

Precision medicine (AI-driven dosing or patient stratification is viewed as high-risk and needs special safeguards and fallback plans)

Product information (if AI is used to draft or translate product labels, companies must have rigorous quality checks to ensure accuracy)

Manufacturing (AI in production should follow ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management and GMP principles)

Pharmacovigilance/post-market (AI tools for adverse event case processing or post-authorisation studies must be closely monitored and agreed with regulators when used to fulfill regulatory obligations).

EMA advocates a risk-based approach similar to FDA’s – higher-risk or higher-regulatory-impact AI applications warrant greater scrutiny and early dialogue with regulators. Technical considerations are addressed in depth: the paper discusses data bias mitigation, robust model development documentation, validation on independent datasets, performance metrics, and the need for explainability (allowing “black-box” models only if transparent models are inadequate, and with extra documentation).

It also touches on ethical AI (referring to EU Trustworthy AI principles and requiring impact assessments) and data protection compliance (e.g. anonymization when using personal data in AI, conducting AI-specific data protection impact assessments).

Overall, EMA’s guidance is nearly as detailed as FDA’s, albeit in a reflection paper (which is non-binding but influential) rather than formal guidance. EMA has indicated that outstanding issues not fully addressed in the reflection paper will be taken up in future, more specific scientific guidance (likely once the EU AI Act is finalized).

Strategic Initiatives

EMA’s efforts are guided by a Multi-Annual AI Workplan (2023–2028) developed (ema.europa.eu) with the EU Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA) Big Data Steering Group. Published in December 2023, this workplan lays out a coordinated strategy to “maximize the benefits of AI without falling into its risks,” focusing on four pillars:

Guidance & policy – delivering guidances (like the AI reflection paper) in areas including pharmacovigilance and preparing for the forthcoming EU AI Act.

AI tools & technology – equipping regulators with AI for efficiency (e.g. in March 2024 EMA launched “Scientific Explorer,” an AI-powered knowledge mining tool for regulatory documents) and ensuring compliance (e.g. with data protection) for any AI use.

Collaboration & training – partnering with international peers and building internal expertise (e.g. creating an AI special interest group and expanding the EMA’s Digital Academy for regulators).

Experimentation – running pilot projects and “sandbox” exercises from 2024–2027 to test AI applications, and developing guiding principles for responsible AI use .

EMA also set up an AI Observatory in 2024 to track emerging trends and applications of AI in medicines regulation. The first annual AI Observatory Report (2024) was published in July 2025, compiling EU regulators’ experiences and a horizon scan of AI in regulation (ema.europa.eu). All these indicate a proactive and evolving strategy at EMA to integrate AI into regulatory science.

Stakeholder Engagement

EMA has actively engaged stakeholders across Europe. The reflection paper itself underwent a public consultation – a draft was released in July 2023 and comments from a wide range of stakeholders were reviewed over many months. To further dialogue, EMA and HMA jointly hosted a multi-stakeholder workshop on AI in November 2024, bringing together regulators, pharma companies, academics, healthcare professionals, and patient groups.

This workshop (ema.europa.eu) discussed responsible AI use at each stage of drug development and highlighted the need to adapt regulatory and policy frameworks in light of AI’s risks and benefitst. EMA also engages through its EU Innovation Network and ad-hoc forums – for example, specific AI tools can be assessed via EMA’s qualification advice process (indeed, in March 2025 EMA issued its first qualification opinion for an AI-driven methodology, endorsing an AI tool for pathology in NASH clinical trials).

This qualification involved a draft opinion open for public comment in Dec 2024–Jan 2025 (ema.europa.eu).

In summary, EMA’s approach shows high stakeholder engagement, with multiple feedback loops (consultations, workshops, published workplans) and transparency about how AI policy is developing. The EMA efforts are also timely – aligning with the EU’s broader digital strategy (e.g. coordinating with the proposed EU AI Act and updating internal policies like staff guidelines for using AI, such as LLM guiding principles issued Sept 2024). The reflection paper and workplan together give EMA a strong, current foundation, although further detailed guidelines are expected as technology and legislation evolve.

MHRA (United Kingdom) – AI Strategy and Regulatory Sandbox

Regulatory Strategy

The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) set out an AI Regulatory Strategic Approach in April 2024 to guide its activities through 2030 (gov.uk). Rather than a single guidance document for industry (as FDA and EMA have), MHRA’s strategy is a high-level plan aligning with the UK government’s pro-innovation AI regulation policy It lays down five key principles for AI in healthcare: ensuring safety, robustness, transparency, fairness, accountability (these mirror the UK Government’s 2023 AI White Paper principles).

The MHRA’s role is considered from three angles

(1) as a regulator of AI products (including software as a medical device)

(2) as an agency that uses AI internally to improve efficiency

(3) as a consumer of evidence generated by regulated parties who may use AI in R&D and submissions.

This comprehensive (gov.uk) perspective ensures MHRA addresses both external regulation and internal capability.

AI in Drug Development and Trials

While much of MHRA’s concrete guidance so far has focused on AI in medical devices (reflecting rapid innovation in digital health tools), the agency explicitly recognizes AI’s impact on medicines development and clinical trials. The MHRA notes that AI can accelerate drug discovery, influence clinical trial design, and enable personalized medicines, and it is committed to keeping regulatory pathways “sufficiently agile and robust” to accommodate these changes.

For example, MHRA is working through international groups like CIOMS to develop best practices for AI in pharmacovigilance and clinical research. Although by mid-2025 MHRA has not issued a dedicated guidance document akin to FDA’s or EMA’s, it plans to embed AI considerations into existing frameworks (e.g. upcoming guidance on human factors for AI in devices by 2025).

Its 2021–2023 Software and AI as a Medical Device Change Programme already laid a roadmap for AI in medical device regulation (such as up-classifying certain AI devices to higher risk classes).

Notably, MHRA, along with FDA and Health Canada, published guiding principles for Good Machine Learning Practice in medical device development and on adaptive AI algorithms (Predetermined Change Control Plans) to ensure manufacturers remain accountable for AI model updates.

These indicate a depth of technical understanding that MHRA can extend to the medicines arena.

Internal Capacity and Innovation

MHRA is also leveraging AI internally. The agency is piloting AI tools to screen drug marketing authorization applications (e.g. using machine learning to check the completeness and quality of submissions) and to enhance inspection processes. It is developing a comprehensive data strategy covering use of advanced analytics and even exploring large language models for internal use (while cautiously noting uncertainties in their best practice).

Additionally, MHRA is using AI to combat health fraud (e.g. an AI-enabled “Medicines Web Checker” to identify illegal online sales of medicines). These efforts, while internal, reflect a regulator actively experimenting with AI to improve its own effectiveness, which in turn informs how it regulates industry use of AI.

Stakeholder Engagement

The UK is fostering engagement through an “AI Sandbox” approach. In 2023, the government launched an “AI Regulatory Sandbox” (the “AI Airlock”) for healthcare, in collaboration with MHRA, to allow companies developing cutting-edge AI health technologies to work with regulators in a controlled environment.

By mid-2025, MHRA opened a second round of sandbox applications for AI medical technologies after a successful pilot, indicating strong industry interest (and the UK’s commitment to support it). This sandbox provides a forum for industry engagement, enabling developers to get feedback on regulatory requirements early and for MHRA to learn about emerging AI innovations. Apart from the sandbox, MHRA has been participating internationally (it chairs the IMDRF working group on AI medical devices, promoting global regulatory harmonization).

Domestically, MHRA’s publication of its AI strategy was accompanied by public statements and it aligns with the broader UK AI policy that underwent public consultation. Thus, while MHRA’s engagement approach is somewhat different (fewer formal guidances, more collaborative initiatives), it scores well on industry engagement and flexibility.

The MHRA strategy was prompted in part by a government request (Feb 2024) for regulators to detail how they’re adopting the national AI principles, showing timeliness: MHRA responded quickly, and is already implementing changes (e.g. updating device regulations by summer 2025, developing new guidance on cybersecurity for AI).

Overall Assessment

The MHRA’s AI regulatory framework is broad but in early stages for medicines. It emphasizes principle-based oversight and creating an innovation-friendly environment. In terms of depth, it is not as immediately granular as FDA/EMA (since specific drug trial guidance is still forthcoming), but its comprehensive strategy and ongoing updates (planned guidance by 2025, new regulations for AI-based devices, etc.) indicate a commitment to evolve rapidly.

Its stakeholder engagement via sandboxes and international collaborations is a strong point, potentially allowing more interactive input from industry than traditional consultation alone.

Swissmedic (Switzerland) – Emerging Sectoral Approach and Innovation Focus

Regulatory Context

Switzerland, while not in the EU, has been actively considering (swissmedic.ch) how to regulate AI in healthcare through a sector-specific approach. In February 2025, the Swiss Federal Council announced a national approach to AI regulation that integrates AI requirements into existing sectoral laws (instead of a single “AI Act”). This means areas like medical devices and pharmaceuticals will incorporate AI considerations within their current regulatory frameworks. The goal is to support innovation in Switzerland (maintaining the country’s attractiveness for AI development) while managing risks to society.

For pharmaceuticals, Swiss authorities indicated they will rely on international standards (ICH guidelines, GxPs) and align with global best practices for AI in drug development. In practice, Swissmedic (the Swiss therapeutic products agency) often adopts or references EMA and ICH guidances, so it is expected to follow the principles from EMA’s AI reflection paper and upcoming ICH work on AI.

Current Status and Depth

As of mid-2025, Swissmedic has not issued its own standalone public guidance on AI in drug development. However, it has been laying groundwork internally and through international cooperation. From 2019–2025, Swissmedic ran a “Swissmedic 4.0” digital initiative explicitly aimed at building competencies in digitalization, AI, data science, and novel technologies among its staff. This internal incubator allowed Swissmedic to experiment with AI tools (e.g. prototyping AI-based risk assessment models for medical device evaluation) and to train reviewers on AI and data literacy.

he 4.0 team facilitated workshops and seminars on AI/ML for Swissmedic staff, often bringing in knowledge from international partners like EMA and FDA. This knowledge transfer means Swissmedic regulators are becoming well-versed in AI, even if formal guidance to companies is pending. A

Additionally, Switzerland participates as an observer or member in various international forums (Swissmedic is part of the Access Consortium with Canada, Australia, etc., and hosted meetings on AI via the IMDRF in 2025). These engagements likely influence Swiss regulatory stance on AI (imdrf.org).

Sector-Specific Measures

In the medical devices realm, Swissmedic’s oversight of AI is constrained by Switzerland’s relationship with EU law. Swissmedic indicated that Swiss laws for devices will need updates to address AI, but in practice Swiss manufacturers must already comply with EU device regulations (MDR/IVDR) and soon the EU AI Act for any product marketed in the EU. This limits divergence. There have been suggestions (by policy experts) that Switzerland could create a dedicated AI and Digital Health Center to streamline AI approvals domestically, potentially giving Swissmedic new tools like regulatory sandboxes or fast-track pathways for AI-driven products.

While this is not yet reality, it shows Switzerland’s intent to be competitive and innovation-friendly in AI regulation. For pharmaceuticals specifically, Swissmedic in 2023 identified “AI-assisted drug development and research” and “AI in drug manufacturing” as key components of the “evidence-based authorization of the future” in its regulatory science outlook (swissmedic.ch). This suggests that Swissmedic is aware of AI’s growing role and is evaluating how to adapt processes (e.g. accepting AI-derived evidence in submissions, ensuring GCP compliance in AI-run trials, etc.).

Stakeholder Engagement

Swissmedic’s external engagements on AI have so far been modest compared to FDA/EMA. There is no published Swissmedic consultation on AI guidelines yet. However, Swissmedic and Swiss authorities have engaged stakeholders through broader initiatives. For example, the Federal Council’s AI regulatory approach was developed with input from multi-agency analyses (a 2022 sectoral analysis of AI in medtech was conducted).

Swissmedic representatives likely contribute via HMA and ICH forums, indirectly voicing Swiss industry perspectives. Domestically, Swissmedic regularly meets with industry (e.g. Roundtable Medtech meetings); the October 2024 roundtable included discussion of AI guidance (“GPI”) with a plan to publish principles by early 2025 (swissmedic.ch). Moreover, Switzerland’s innovation agency and Ministry of Health have supported digital health and AI programs, such as calls for sandbox proposals in healthcare AI.

These provide industry a chance to pilot AI solutions under supervision, analogous to the UK sandbox concept. In summary, stakeholder engagement in Switzerland is building but is not as institutionalized as in larger jurisdictions. Swissmedic’s approach to AI regulation is still emerging – it is expected to track EMA closely (given the need to avoid a “Swiss finish” divergence that could burden companies) while using targeted national measures to encourage AI innovation. As of July 2025, the Swiss framework can be considered moderate in depth (no specific guidance yet) but high in awareness, with significant internal capacity-building and a policy commitment to update regulations sector-by-sector.

Israel – Ministry of Health Guidelines and Principles

Regulatory Guidance

Israel’s Ministry of Health (MOH) has been proactive in issuing guidance on AI for clinical research and product development. Notably, Israel released draft guiding principles for AI/ML technology development as early as December 2022. These principles (10 in total) were modeled after international best practices (citing FDA, Health Canada, and MHRA’s work on GMLP) and cover areas such as multi-disciplinary design, data security, bias avoidance, independent model validation, performance transparency, and continuous risk management for AI models.

The aim is to lay a foundation for “Good Machine Learning Practice” in health tech development in Israel. The MOH sought feedback from healthcare organizations, startups, and the public on this draft through January 2023, showing an early commitment to stakeholder input.

AI in Clinical Trials

Building on that, Israel in late 2024 published “Key Principles for Evaluating AI-Driven Interventional Trials”– one of the first guidances globally focused on AI in clinical trial contexts. This MOH publication (Dec 2024) provides a framework of questions and considerations for Helsinki Committees (Israel’s institutional review boards) when assessing clinical trial proposals involving advanced AI tools.

It essentially acts as an AI-specific ethics and safety checklist to ensure such trials protect participants and maintain scientific integrity. The guidance identifies three categories of AI-related studies across a trial lifecycle:

(a) Model development studies – e.g. training multiple AI models on retrospective data, with emphasis on data privacy and proper model selectio

(b) “Silent” prospective studies – AI is run in real-time alongside care but does not influence treatment, used to validate the AI’s predictions in the real world (raising issues of system integration and cybersecurity if running in hospital IT environments)

(c) Active prospective studies – where the AI actively aids or drives clinical decisions/treatment (this demands careful ethical review of how AI might affect patient outcomes, doctor oversight, and how errors are prevented).

For each type, the MOH guidance lists detailed questions for IRBs about algorithm performance, data handling, patient consent regarding AI, and risk mitigation (for example, ensuring human clinicians can override AI recommendations in active studies). This guidance essentially operationalizes a risk-based oversight at the clinical trial level, complementing broader regulatory evaluation at product approval stages.

Depth and Coverage

Israel’s AI guidances, while narrower in scope than FDA/EMA’s full lifecycle approach, are deep in their specific domains. The 2022 principles cover technical development practices comprehensively (similar to global GMLP principles)g. The 2024 trial evaluation guidance is quite detailed ethically/clinically and is among the first of its kind. These position Israel as an early adopter of formal AI guidelines in the drug development arena, despite the country’s smaller market size.

Israel is also known for its strong digital health startup sector, so the MOH’s focus ensures local innovators have clarity on regulatory expectations early on (for example, how to design AI-driven clinical studies or decision-support tools that will pass ethical and regulatory muster).

Timeliness and Updates

The MOH has shown a pattern of consultation and iteration. The draft development principles (Dec 2022) were updated after feedback, and the trial principles (Dec 2024) were released with an invitation for public comment by April 1, 2025. This suggests the MOH intends to refine and possibly formalize these guidelines after stakeholder input, keeping them up-to-date. The Israeli regulatory framework for AI is thus very current – tackling issues like generative AI and real-world data use as they emerge.

Moreover, Israel’s government approved a national AI program and various AI ethics policies in recent years (gov.il), which provide a supportive policy backdrop for MOH’s sectoral guidelines. As of mid-2025, Israel’s guidelines are in draft or interim form, but they are well-aligned with global trends and being updated in real-time via feedback loops.

Stakeholder Engagement

The engagement level is high for Israel’s efforts. Both major publications were open for feedback (the MOH explicitly solicited “suggestions from the health-tech ecosystem and the general public” for the 2022 principles, and likewise for the 2024 trial guide). The development of these documents was overseen by dedicated committees of experts, indicating industry and academic representation. In addition, Israel leverages initiatives like its Digital Health Sandbox (Be’er) and innovation authority programs to involve companies in pilot projects for AI in healthcare (gov.il).

There has also been public discourse – for instance, Israeli medical organizations calling on the MOH to set AI usage guidelines to ensure patient safety. The MOH appears responsive to such calls. In summary, Israel’s medicines regulators have a focused yet robust approach: their regulations score high in completeness within the domains they target (AI development best practices and AI in trials), and high in engagement, given the collaborative, consultative process and the agility in incorporating new global insights.

Norway – Alignment with EMA and Global Collaboration

Regulatory Alignment

Norway’s Medicines Agency (NoMA, also known as Statens Legemiddelverk) operates within the European Economic Area and thus aligns closely with EMA. Norway participates in the HMA/EMA network, so the EMA Reflection Paper on AI (2024) and related EU guidances are essentially adopted as the standard in Norway’s regulatory practice. In other words, while Norway hasn’t issued a separate national AI guidance for pharmaceuticals, it supports and implements the EMA’s guidance and upcoming EU AI Act provisions within its jurisdiction.

For example, if a company conducts AI-supported clinical trials or includes an AI component in a drug submission in Norway, the expectations would mirror those described by EMA (compliance with GCP, data integrity, etc.). Similarly, for medical devices with AI, Norway is updating its regulations in tandem with Europe – the Norwegian Medicines Agency continues to enforce the legacy EU Medical Device framework, and pending new legislation, many AI-based devices will be up-classified to higher risk classes to ensure more rigorous oversight.

National Strategy and Initiatives

The Norwegian government released a National AI Strategy (2020) emphasizing safe and trustworthy AI, and health is a key domain in that strategy (regjeringen.no). While the strategy primarily addresses broad issues (data sharing, ethics, etc.), it notes that agencies like the Norwegian Medicines Agency will provide guidance and supervise AI-driven medical technologies under existing laws (regjeringen.no). In 2024, Norway’s health authorities (including the Directorate of Health and NoMA) developed a Joint AI Action Plan 2024–2025 to promote safe use of AI in health services (helsedirektoratet.no).

This plan likely includes creating cross-agency guidance services to advise projects involving AI in healthcare. Such a one-stop guidance service was initiated to help companies or researchers navigate current regulations related to AI (helsedirektoratet.no). These efforts show Norway is working to clarify regulatory pathways for AI in both clinical practice and product development, even if via informal guidance.

Global Engagement

A standout aspect of Norway’s approach is its international engagement and support for global capacity-building in AI regulation. In June 2024, the Norwegian government announced a NOK 45 million investment in a WHO-affiliated initiative called HealthAI – the Global Agency for Responsible AI in Health. This funding supports a 3-year strategy to help low- and middle-income countries develop regulatory standards and networks for AI in healthcare.

The project includes creating global regulatory sandboxes, knowledge exchange platforms, and a public registry of vetted AI health solutions. Norway’s role here underlines its commitment to shaping AI regulation beyond its borders, leveraging its expertise to ensure AI benefits are globally shared. Domestically, this also means Norwegian regulators are at the cutting edge of discussions on AI governance, learning from and contributing to international best practices.

Stakeholder Engagement

Within Norway, stakeholder engagement on AI in drug development occurs largely through participation in the EMA/HMA processes. Norwegian experts and industry had chances to input during EMA’s 2023 consultation on the AI reflection paper and via the multi-stakeholder workshop in Nov 2024 (where Norway was represented under HMA). Norway’s own Medicines Agency has a tradition of dialogue with industry (e.g. regular industry meetings, input on guideline drafts which in this case would be via EMA channels). The cross-agency AI guidance service mentioned above also implies direct interaction with health tech developers in Norway, providing tailored regulatory advice.

Thus, while Norway does not have a distinct AI regulatory framework separate from the EU, it demonstrates high engagement and responsiveness by helping stakeholders navigate AI regulations and by advocating for consistent standards internationally. The timeliness of Norway’s action is on par with EMA – the reflection paper was adopted in 2024 and Norway will integrate its recommendations concurrently.

Norway will also implement the EU AI Act when it comes into force, ensuring up-to-date controls on high-risk AI systems in healthcare. In summary, Norway’s medicines agency scores moderate on depth (no independent guidance, but comprehensive adoption of EMA’s) and high on engagement, especially considering its support for global regulatory development and domestic advisory initiatives. It took its first major steps in the AI regulatory space around 2019–2020 with the European Big Data taskforce and national strategy, ramping up in 2024 with active contributions.

Comparative Assessment of AI Regulation Approaches

All these regulatory agencies acknowledge the transformative potential of AI in drug development and the need for oversight that protects patients without stifling innovation. However, their approaches vary in completeness of guidance, recency of updates, and stakeholder engagement intensity.

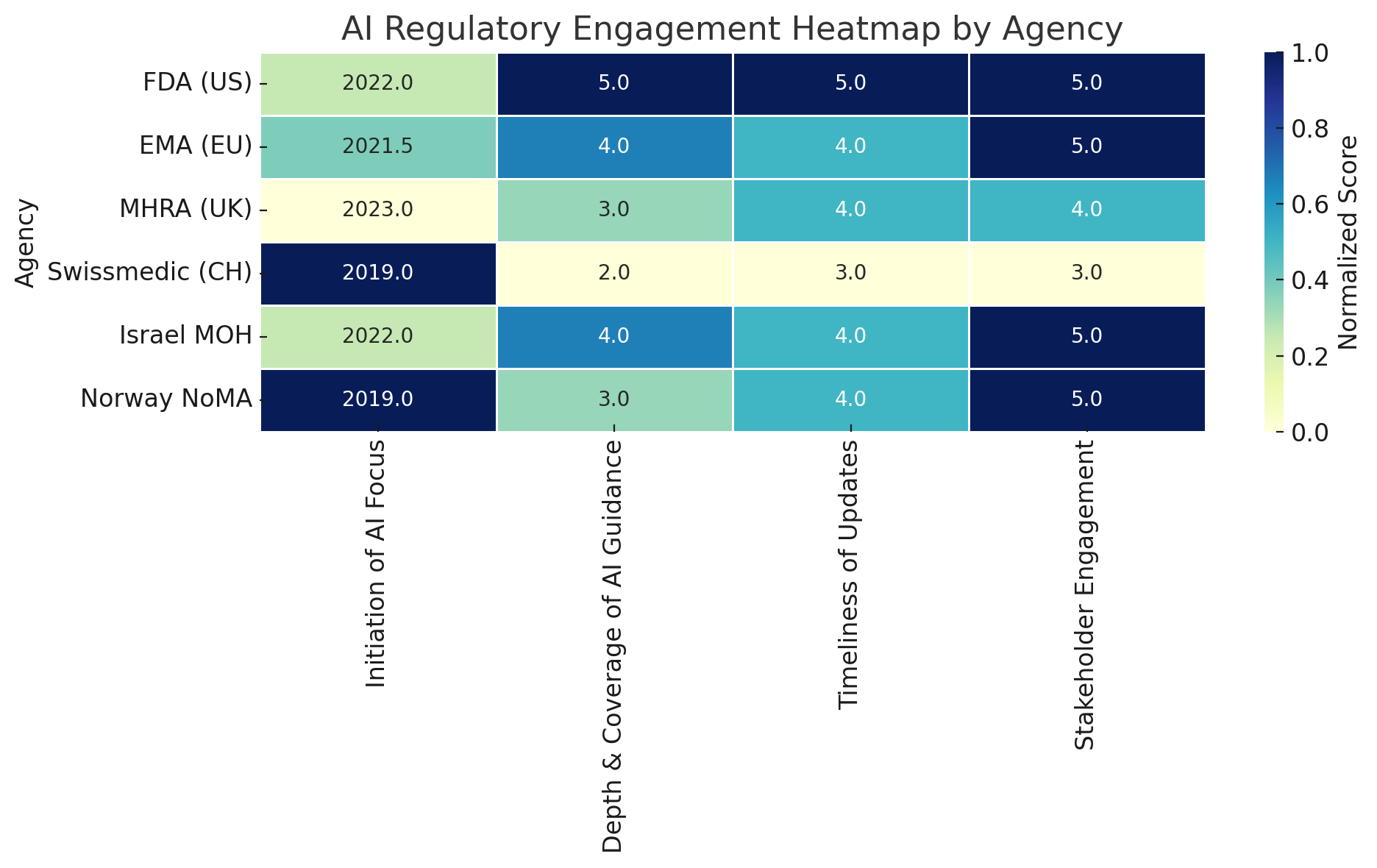

This heatmap offers a comparative view of how six prominent regulatory agencies are addressing artificial intelligence (AI) in the context of drug development and healthcare regulation. Each row represents a regulatory authority—ranging from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to Norway’s NoMA—and each column reflects one of four key dimensions of regulatory activity. These dimensions were selected to capture the breadth and maturity of institutional approaches to AI oversight.

The first dimension, Initiation of AI Focus, records the approximate year in which each agency began formal work on AI. Here, the score is inversely related to the year—agencies that only recently began their AI efforts receive higher ratings, based on the rationale that newer engagement often reflects more proactive or timely alignment with current technological advancements. For example, a start date of 2022 would be rated higher than one from 2019. This metric helps distinguish early adopters from agencies that have only recently recognized AI as a regulatory priority.

The second dimension, Depth and Coverage of AI Guidance, evaluates the extent to which each agency’s guidance spans the entire drug or health technology lifecycle. This includes nonclinical development, clinical trials, manufacturing processes, post-market surveillance, and adaptive algorithms. Agencies are scored on a 1–5 scale, with “5” indicating highly specific and detailed coverage and “1” reflecting minimal or superficial mention of AI-related regulatory implications.

Timeliness of Updates serves as a proxy for regulatory agility. It considers whether an agency has issued recent updates, public strategies, or iterative guidance reflecting the fast-moving nature of AI technologies. A high score in this category indicates that the agency is actively revising and modernizing its approach, rather than relying on static or outdated documents.

The final dimension, Stakeholder Engagement, measures the degree to which regulators consult with industry, academia, and civil society through mechanisms such as public consultations, technical workshops, innovation sandboxes, or multi-stakeholder roundtables. Here, a high score reflects both the diversity of stakeholders engaged and the openness of the process.

To make comparisons meaningful, all values are normalized across columns. For example, initiation years are translated into a relative score (with more recent years scoring higher), and qualitative metrics are converted into a standardized 1–5 scale. The resulting color intensity in the heatmap reflects these normalized values—darker blue signifies stronger performance within that dimension.

From this analysis, several patterns emerge. The FDA (US) and Israel’s Ministry of Health (MOH) emerge as the most engaged regulators across all four dimensions. Both have issued targeted guidance, updated it regularly, and consulted widely with external experts. The EMA (EU) and the MHRA (UK) follow closely, each having published structured AI strategies and made substantial efforts to align their guidance with evolving industry needs. Swissmedic (CH), by contrast, appears more conservative in its approach. While it has made internal investments in digital capacity, its AI-specific output is limited, and it generally defers to EMA and ICH standards. Finally, Norway’s NoMA, despite not issuing its own standalone AI guidance, scores highly in collaborative engagement—reflecting its integration into European and international initiatives, and its domestic cross-agency AI strategy.

This heatmap does not aim to rank agencies definitively but to provide a structured lens through which to compare varying regulatory postures toward AI. It highlights both areas of leadership and gaps in global alignment—crucial insights as AI continues to reshape the life sciences landscape.

Appendix

Comparison of AI Regulatory Frameworks (Depth, Timeliness, Engagement) - Detailed Overview

| Agency | Initiation of AI Focus | Depth & Coverage of AI Guidance | Timeliness of Updates | Stakeholder Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA (US) | ~2022 (AI workshop & discussion paper) | Very High – Detailed draft guidance covering nonclinical, clinical, manufacturing, post-market (full lifecycle). Technical specifics (validation, bias, explainability) in depth. | Up-to-date – Draft guidance released Jan 2025; iterative updates planned after 800+ comments. Ongoing internal AI council (2024) keeps policy current. | Extensive – Multiple public consultations, >800 comments on discussion paper. Expert workshops in 2022 and 2024. Engages academia/industry via Duke-Margolis events and public meetings. |

| EMA (EU) | ~2021–2022 (Big Data TF & draft reflection) | High – Reflection paper (final 2024) spans entire medicine lifecycle from discovery to post-authorisation. Comprehensive principles (risk-based, GxP-aligned) but at high-level; future granular guidances planned. | Up-to-date – Reflection paper adopted Sept 2024; AI Workplan 2023–2028 guiding ongoing actions. Aligning with EU AI Act (2025/26) and issuing new updates (e.g. staff AI use principles in 2024). | Extensive – Public consultation on draft (mid-2023). Multi-stakeholder workshop Nov 2024 with regulators, industry, academics, patients. Big Data Steering Group includes industry input; Observatory collects feedback. |

| MHRA (UK) | ~2023 (response to UK AI policy; prior SaMD work from 2021) | Moderate – AI strategy (2024) outlines broad principles and planned guidance. Strong on AI in devices (GMLP, adaptivity); acknowledges drug development impact but specific guidance for trials or AI in submissions still in development. | Current – Strategy published Apr 2024. Rolling out specific guidances by 2025 (e.g. cybersecurity, human factors for AI). Regulatory sandbox piloted 2023 and expanded 2025 to keep pace with innovation. | High – Uses Innovation Sandbox (AI “Airlock”) allowing companies to test AI tech with regulators. International collaboration (chairs IMDRF AI group). Engages via blog updates, workshops, and multi-sector feedback. |

| Swissmedic (CH) | ~2019 (Swissmedic 4.0 initiative launch); 2025 nat’l AI policy shift | Low/Moderate – No dedicated AI guidance issued to industry yet. Reliant on global standards (ICH, EMA). Internal capacity built via Swissmedic 4.0 (trained staff, pilot AI tools). | Transitional – Currently adopting a new sectoral AI framework (2025). Will update laws as needed per sector (e.g. device law changes pending for AI). Keeping abreast via EMA/HMA outputs and adapting gradually. | Moderate – Some engagement through international forums (HMA, IMDRF, Access Consortium). Fostering innovation via national programs and roundtables. Fewer formal public consultations specific to AI in pharma. |

| Israel MOH | ~2022 (draft AI principles); 2024 AI trial guidelines | Focused/High – Targeted guidances: Draft GMLP principles for AI in health tech dev (10 key principles), and IRB guidance for AI-driven clinical trials. Covers ethics, data, and risk in trial use of AI in detail. Lacks a full product lifecycle guide, but key areas addressed thoroughly. | Up-to-date – Draft principles released Dec 2022, incorporating latest international thinking. Trial guidance Dec 2024, with feedback period into 2025. Will likely finalize post-comments. | High – Open consultations for both 2022 and 2024 documents. Engaged local hospitals, startups, academia via dedicated committees. Israel Innovation Authority programs encourage industry input. Rapid responsiveness to calls for AI regulation. |

| Norway NoMA | ~2019 (EMA Big Data Taskforce involvement); 2020 nat’l AI strategy; 2024 HMA/EMA workshop | Moderate – No standalone guidance; implements EMA’s comprehensive framework within EEA. Focus on AI in devices via EU rules; for drugs, relies on EMA/ICH standards. | Up-to-date – Follows EMA timeline (2024 reflection paper). Will mirror EU AI Act when effective. National cross-agency AI plan 2024 ensures current oversight tools. Regularly updates in tandem with EU. | High (Collaborative) – Active in EMA/HMA multi-stakeholder efforts. Offers guidance service to AI projects domestically. Globally, invested in HealthAI to build regulatory capacity worldwide. |

Legend: Depth & Coverage = how comprehensive and detailed the agency’s AI regulatory guidance is. Timeliness = how recent and frequently updated the AI-related regulations are. Stakeholder Engagement = extent of industry/external involvement (consultations, workshops, sandboxes, etc.). The assessments (High/Moderate/Low) are relative to the group of agencies considered.

Member discussion