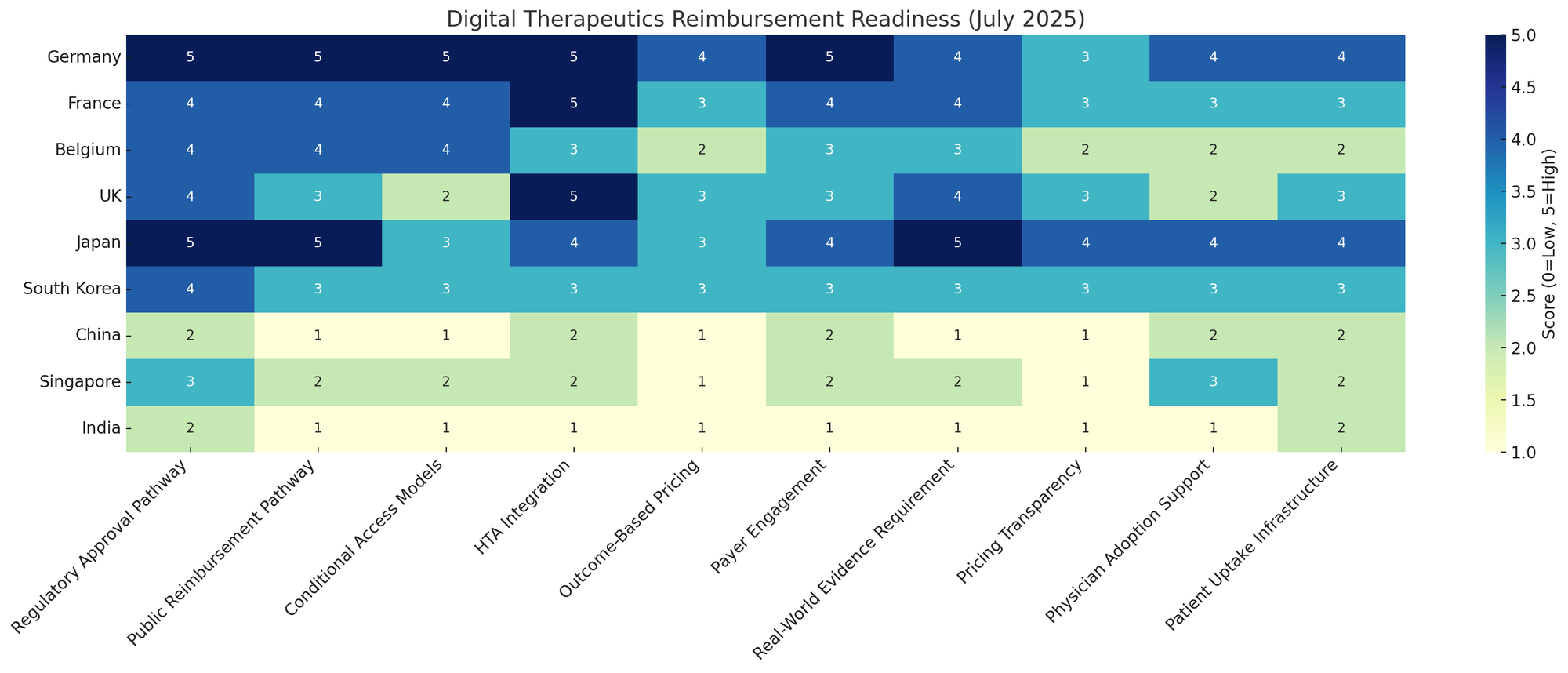

Digital Therapeutics Reimbursement Models in Europe and Asia

Overview of Digital Therapeutics and Reimbursement

Digital therapeutics (DTx) are evidence-based software interventions prescribed to treat or manage medical conditions. As these “apps-as-medicine” gain regulatory approvals, reimbursement models have emerged as a key factor in their adoption. Governments and insurers in Europe and Asia have begun implementing pathways to cover DTx under national health systems – a critical step to drive usage beyond out-of-pocket payers.

Below, we examine how various countries have structured DTx reimbursement, the history and status of these models as of July 2025, whether they have delivered on promises, and how pricing for DTx has evolved. We focus on leading examples in Europe (notably Germany and France, among others) and Asia (Japan, South Korea, etc.), incorporating payer perspectives and the implications for pricing and investment.

Europe: Pioneering Digital Therapeutics Reimbursement

Europe has led the way in creating formal reimbursement pathways for digital health applications. Several countries now allow physicians to prescribe digital therapeutics like medications, with costs covered by public health insurance. The most developed systems are in Germany and France, with other nations following suit on a smaller scale. European payers have embraced DTx cautiously – recognizing their potential to improve care, but also demanding evidence of clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness.

Germany: The DiGA Fast-Track Experience

Germany was the first country to implement a nationwide DTx reimbursement framework, through the 2019 Digital Healthcare Act. This created the “DiGA” fast-track process (Digitale Gesundheitsanwendungen) which launched in 2020. Under this model, DTx that obtain a CE mark and pass basic security/quality checks can be provisionally listed in an official DiGA directory, even with only preliminary evidence. Doctors can prescribe these apps, and statutory health insurers reimburse them immediately – essentially treating approved apps “like pills.”

Manufacturers set an initial price freely for the first year on the market, after which they must negotiate a permanent reimbursement price with the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance (GKV-Spitzenverband). This fast-track aimed to spur innovation by lowering entry barriers for digital startups that lack extensive clinical trial data up front.

Uptake and Outcomes: In the first four years, Germany’s DiGA initiative has grown rapidly in utilization but faced scrutiny on its value delivery. By the end of 2024, 861,000 app prescriptions had been issued in total, with €234 million in cumulative reimbursement spending. Annual spending has accelerated as more apps and prescriptions came online – GKV reports that 2024 spending (€110M) was 71% higher than 2023 (€64M).

Over 60 DTx apps have been listed so far (68 by end of 2024), addressing a range of conditions from mental health and musculoskeletal disorders to diabetes. This volume demonstrates clear demand and interest from patients and physicians. However, the payers’ perspective is increasingly critical: only 12 out of 68 apps (18%) had proven health benefits at the time of listing, with the vast majority entered under “conditional” status pending evidence. In fact, about half of the provisionally listed apps were later removed for failing to show a positive patient outcome.

German health insurers and regulators have thus questioned whether the system has been “paying for promises or for proof,” given that many DTx were reimbursed without robust clinical results upfront.

By 2025, only a minority of DiGAs have demonstrated meaningful outcome improvements, prompting reforms to tighten evidence requirements.

Pricing and Payer Pushback: Germany’s DiGA program also shed light on DTx pricing dynamics in a reimbursed market. In the initial phase, manufacturers often set high prices – on average about €400 per 90-day treatment, with some as high as €950 for 3 months. Statutory insurers complained these prices were “arbitrarily set” without relation to traditional care costs (healtheconomicsreview.biomedcentral.com). After the first year of free pricing, negotiations have drastically reduced prices by roughly 50% on average. In practice, the median reimbursed price after negotiation settled around €220 per 90 days (vs. initial ~€540).

This indicates significant price pressure once payers weigh the evidence and cost-benefit of each app. German payers have even proposed eliminating the one-year free pricing period entirely – recommending that negotiated prices apply from day one of listing to avoid overpaying for unproven apps.

Moreover, starting in 2026 Germany will introduce outcome-based reimbursement: at least 20% of a DiGA’s payment will be conditional on achieving defined success metrics in real-world patient outcomes (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). This marks a shift to pay-for-performance, aligning payment with actual effectiveness. These measures reflect a payers’ perspective focused on value: the head of GKV has questioned whether any part of the €234M spent so far has led to measurable health improvements.

Insurers are pushing for stronger evidence, cost-effectiveness analyses, and even usage-based pricing (paying only for apps that patients actively use) to ensure DTx deliver tangible benefit for the money spent.

Despite these challenges, Germany’s experiment has been pioneering. It proved that “apps on prescription” can be integrated into routine care at scale, but also highlighted the need for rigorous evaluation. As of 2025 the DiGA model is at a crossroads: nearly 900,000 patients have tried a DTx via prescription, yet the “proof-of-value” is under scrutiny. Going forward, Germany is raising the bar – requiring more upfront clinical data (especially for higher-risk Class IIb devices) and mandating transparency of patient-reported outcomes and usage statistics.

In short, the DiGA fast-track delivered rapid adoption and a new market for DTx, but at the cost of “digital inflation” in healthcare budgets. Now the focus is on converting that into verified health benefits. Investors eyeing the German DTx market should note both its first-mover advantages (established prescribing and payment infrastructure) and the increasingly stringent demands for clinical and economic value.

France: PECAN Fast-Track and the Path to Permanent Coverage

France has emerged as another leader in digital therapeutics reimbursement, with a model inspired by Germany but adapted to French healthcare. In March 2024, France introduced “PECAN” (Prise en Charge Anticipée Numérique) – a fast-track scheme for early reimbursement of digital health apps and remote monitoring tools. Often dubbed “apps like pills”, the PECAN program allows DTx to be temporarily covered by statutory insurance for up to 12 months while evidence is gathered. During this period, patients can be prescribed the app and the costs are reimbursed by the French system, giving developers a chance to prove real-world efficacy.

How PECAN Works: To qualify for PECAN listing, a digital therapeutic must have CE marking (as a medical device) and meet strict criteria for quality, data security (GDPR compliance), and interoperability. Crucially, the developer must show potential clinical benefit and a plan to collect outcome evidence during the trial period. The evaluation involves the French Digital Health Agency and a review by the national HTA body, Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS), all within a target of 90 days (icthealth.org). If approved by the Ministry of Health, the DTx is added to the list of reimbursed products (Liste des Produits et Prestations, LPPR) but only for a limited time (generally 6–12 months).

By 6–9 months in, the manufacturer must submit clinical study results to HAS to seek permanent reimbursement. This is a shorter evidence window than Germany’s (which allowed up to 24 months conditional listing), reflecting France’s stricter stance on quickly validating effectiveness. Notably, PECAN also covers telemonitoring solutions (remote patient monitoring software/devices) in addition to standalone therapeutic appsicthealth.org, and it allows all risk classes (I–III) to apply, whereas the German DiGA path had been limited to lower-risk classes.

Early Experience: As of mid-2025, France’s PECAN is still in its infancy. Getting listed in PECAN has proven challenging, with high standards for data and clinical rationale. In fact, the first known DTx submission – an insomnia therapy app (HelloBetter Insomnie) – received a negative opinion from HAS in mid-2024, failing to pass the evaluation. The developer (HelloBetter, a German company with multiple DiGAs) reported that theirs was the “first and only” DTx dossier submitted under PECAN so far. This illustrates that France’s bar for “innovativeness” and expected benefit is quite high; not every app that succeeded in Germany will qualify in France.

The French approach emphasizes that PECAN is not meant to be a testbed for every health app, but rather a controlled pathway for high-quality, promising solutions. We have yet to see a breakthrough success in PECAN (no public announcements of a DTx getting temporary reimbursement as of July 2025), but the infrastructure is in place. Meanwhile, France has also been working on the permanent reimbursement side: once a DTx proves its worth, it can enter mainstream coverage via LPPR listing (the national reimbursement list for medical devices/health products).

The Plan France 2030 commits significant funding (€718 million) to digital health adoption, indicating strong political will to make France a “digital health powerhouse.” The expectation is that PECAN will funnel the best DTx into long-term reimbursement, supported by robust evidence and pricing negotiated by the Economic Committee for Health Products (CEPS) in the usual French manner.

From a payer perspective, France’s system tries to balance innovation with prudence. By granting early market access, it supports startups and patient access, but by requiring quick proof (within a year), it avoids long-term spending on unvalidated apps. Payers in France have historically been cautious – prior to 2024, digital therapeutics had no clear path to reimbursement, forcing French patients to pay out-of-pocket or rely on research pilots. PECAN’s creation signals that insurers now recognize the value of DTx (especially for chronic diseases like diabetes, depression, etc.) and are willing to invest, but only in exchange for evidence of real patient benefit.

Pricing information for PECAN-listed apps is not yet public, but it’s expected that France will use its existing framework (LPPR pricing negotiated based on clinical benefit and improvement in medical service). Given France’s generally strict pricing for medical technologies, DTx makers should anticipate tough negotiations after the initial phase.

In summary, France in 2025 has one of Europe’s most developed digital health reimbursement strategies on paper, combining temporary reimbursement (PECAN) and permanent listing (LPPR).

The key question is whether this yields faster adoption than Germany’s approach or simply higher requirements. For investors, France’s commitment (financial and regulatory) is a positive sign, but the selectivity of HAS means only DTx with strong value propositions will thrive. The next 1–2 years should reveal if any “hero apps” manage to go through PECAN and demonstrate outcomes that warrant full reimbursement. Success stories there could set benchmarks for DTx pricing and evidence in Europe.

Other European Initiatives (UK, Belgium, Nordics, etc.)

Beyond Germany and France, several other European countries have initiated their own models for DTx reimbursement or integration into healthcare. While none are as mature, these efforts illustrate a continental trend toward legitimizing digital therapeutics:

Belgium – Validation Pyramid

Belgium created the mHealthBelgium “validation pyramid” in 2019, a three-level pathway to assess and reimburse health apps. An app must first be CE-marked (Level 1), then meet interoperability/IT criteria and apply for reimbursement (Level 2). If authorities grant reimbursement for use in a specific care context, it achieves Level 3. In February 2025, Belgium reached a milestone: seven health apps achieved Level 3+ (permanent reimbursement), becoming the first apps reimbursed under the system. These apps – including cardiac telemonitoring tools like FibriCheck and moveUP – are reimbursed as part of a defined care pathway for chronic heart failure, in hospitals that signed agreements with the national insurer (INAMI).

Notably, Belgium distinguishes Level 3- (temporary reimbursement for data collection) from 3+ (proven socio-economic benefit, permanent). This resembles France’s staged approach. While Belgium’s program is narrower (focused initially on heart failure management), it demonstrates that regular reimbursement for DTx is now happening in multiple EU countries. The Belgian model highlights evidence of cost-benefit (“social-economic added value”) as a gating factor for permanent coverage. For digital health companies, Belgium offers a pathway, though likely with smaller volume than Germany/France due to the targeted scope.

United Kingdom – Integrating DTx via NICE

The UK has not established a dedicated “DTx formulary” like DiGA, but it is incorporating digital therapeutics through existing health technology assessment processes. The NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) has developed an evaluation framework for digital health technologies and has begun recommending certain DTx on the NHS. For example, in 2022 NICE issued guidance endorsing digital CBT apps for insomnia (notably Sleepio) as an effective alternative to sleeping pills (businesswire.com). NICE’s 2025 strategy explicitly aims to “expand technology appraisals to devices, diagnostics, and digital products” as part of a digital shift in the NHS.

In practice, this means DTx will be assessed for clinical and cost-effectiveness like drugs or medical devices. If deemed beneficial and cost-saving, they can be commissioned in NHS services. Some English regions have already launched pilots where certain apps are free to patients via the NHS app library or prescriptions. The UK also introduced an “Innovator Passport” in 2023–2024 to streamline adoption of innovative medtech (including digital) in the NHS. While the UK doesn’t have national reimbursement pricing for apps (the NHS generally negotiates procurement contracts or provides funding centrally), these moves show a clear intent to cover digital therapeutics that prove their value.

For instance, an NHS program might pay a subscription fee for an anxiety treatment app that NICE approves, making it free for patients. UK payers emphasize strong evidence – NICE’s endorsement serves as a quality filter. Thus, from an investment view, the UK could become a major DTx market, but market access will hinge on meeting rigorous NICE thresholds for cost-effectiveness.

Nordic Countries

In Scandinavia, the approach has been more exploratory. Denmark launched a Board for Health Apps (under the Danish Health Authority) to evaluate and recommend health apps for use in the healthcare system. In June 2025, this board issued its first recommendations for 5 apps (covering areas like diabetes management, mental health, etc.), which will be offered to patients with official endorsement.

While not outright “reimbursement,” this is a step toward public funding or insurance coverage for those apps in Denmark. Sweden and Norway have been conducting pilots and HTA reviews of digital interventions, but formal reimbursement frameworks are still in development as of 2025. These countries often leverage robust public healthcare systems and may integrate DTx through regional formularies or specialized programs (for example, a Swedish county might procure an app for pain management and provide it free to patients). The Netherlands has been considering criteria for including digital technologies in basic insurance, focusing on evidence and even sustainability aspects.

Overall, in the Nordics and Netherlands, there is momentum to include digital tools in standard care, but each is crafting its own process rather than a nation-wide DiGA-style law (yet).

Other Europe

Some countries are taking initial steps. Italy and Spain have funded small-scale trials of DTx (often using innovation budgets or research grants), but have not established dedicated reimbursement routes by 2025. However, their participation in EU-wide digital health discussions and the success in neighboring countries could accelerate policy changes.

For example, Italy’s Medicines Agency (AIFA) in late 2022 classified a few digital therapies as medical products, hinting at future coverage decisions. Poland and Central-Eastern Europe are observing the German model; Polish experts have explicitly noted they aim to design their programs with clear entry criteria and outcome-based payments to avoid “exploding costs without evidence” as seen in Germany.

The European Commission is also facilitating knowledge exchange (though healthcare reimbursement remains a national competence). There is no pan-European DTx reimbursement yet, but common threads are emerging: evidence requirements, conditional coverage, and integration with electronic health systems are recurrent themes across Europe.

Insight

For investors, Europe presents a patchwork of opportunities and hurdles. Germany and France offer the largest immediate markets with formal reimbursement, but also the toughest price and evidence pressures. Smaller countries may offer quicker wins in niche areas (as Belgium did in heart failure). The payer perspective across Europe is converging on a demand for proof of clinical efficacy and economic value.

The history so far shows a learning curve – early excitement leading to broad coverage in Germany, followed by a correction toward stricter oversight. Those looking to fund or develop DTx in Europe should plan for thorough clinical trials and health economic studies to satisfy these increasingly discerning reimbursement gatekeepers.

Asia: Early Adoption and Frameworks for DTx Reimbursement

Asia’s landscape for digital therapeutics reimbursement is varied, ranging from world-first approvals in Japan to nascent efforts in other countries. In general, Asian healthcare systems have been slower to create formal reimbursement pathways compared to Europe, but there are notable exceptions. Japan and South Korea stand out as pioneers in legitimizing DTx within public insurance systems. Elsewhere, many Asian markets are still in pilot phases or rely on private sector and out-of-pocket models for digital health. Below we explore the major developments up to 2025:

Japan: First National Insurance Coverage for Prescription DTx

Japan was the first country in the world to reimburse a prescription digital therapeutic under its national health insurance. In December 2020, Japan’s MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) approved coverage for an app-based smoking cessation treatment – the CureApp SC nicotine addiction DTx. This was a landmark: patients diagnosed with nicotine dependence can now be prescribed a digital therapeutic (a smartphone app + CO sensor device) just like a drug, with 70% of the cost covered by Japan’s insurance (standard copay 30%). The reimbursed price of CureApp SC was set at ¥24,000 per patient course (approximately €180), and it is listed in the national fee schedule (japscjournal.com).

This success came after rigorous clinical trials – CureApp SC showed significantly higher 6-month abstinence rates when added to standard therapy. It received regulatory approval as a medical device in August 2020 and quickly after achieved reimbursement, reflecting Japan’s confidence in its clinical benefit. As of 2025, CureApp SC has been used in routine care and is regarded as the first reimbursed DTx in Asia (businesswire.com).

Japan has since approved other DTx and is moving toward reimbursing them as well. CureApp HT, a hypertension management app (the first DTx for hypertension globally), received regulatory approval in 2022. By late 2022 it was reported to have gained insurance coverage and launched commercially across Japan. Another major development was the approval of SUSMED’s insomnia therapeutic app (digital CBT for insomnia) in February 2023. SUSMED’s app is a prescription digital therapeutic providing a 9-week cognitive behavioral therapy program via smartphone for chronic insomnia. As of mid-2023, SUSMED was in the process of applying for insurance reimbursement after its regulatory approval (businesswire.com).

Given the precedent set by CureApp, it is expected that the insomnia DTx will also receive public coverage, making it the third DTx to be reimbursed in Japan (after smoking cessation and hypertension). Indeed, a recent review noted three DTx apps have been approved in Japan (nicotine, hypertension, insomnia) and at least two are already receiving public reimbursement. Japan’s approach essentially integrates DTx into the existing pharmaceutical reimbursement framework: once a DTx is approved as a medical device and its efficacy is recognized, it can be assessed for coverage and assigned a reimbursement price by MHLW, just like a new therapy.

The criteria are stringent – Japan requires solid clinical trial evidence (the “particularly strict” approval standards were a high bar to clear). But when met, the reward is full access to Japan’s large patient population through universal insurance.

Did it deliver? Early indications from Japan are positive in terms of clinical outcomes. For example, real-world use of CureApp SC in clinics has shown improved quit rates for smokers compared to standard care, validating the trial results (as reported in Japanese medical forums). The payers’ perspective in Japan has been cautious but supportive for targeted cases. Because Japan’s public insurance is expansive, any new therapy must demonstrate it is cost-effective to merit coverage. The success of CureApp SC has been touted as proving that digital therapeutics can meet these high standards – Japanese media highlighted it as “ushering in a new era of treatment” (businesswire.com).

The reimbursement of DTx in Japan is notable for being the first in a national system globally, and it signaled to other regulators that software-based treatments can be valued on par with drugs. On pricing, Japan appears to price DTx in line with their perceived therapeutic value and existing treatment costs. For example, ¥24,000 for a 3-month smoking cessation app course is roughly comparable to the cost of prescription medications plus counseling sessions over that period.

Japan also added a new medical fee schedule item in 2022 for “software as a medical device management,” formalizing how doctors prescribe and get reimbursed for DTx follow-up. This ensures physicians are involved (which is culturally important in Japan’s system) and are compensated for the time to manage DTx-based care.

Looking forward, Japan is poised to continue leading Asia in DTx adoption. Its aging population and emphasis on preventive care align well with digital solutions for chronic diseases. The government’s support (including some funding for DTx development via innovation grants) and the precedent of reimbursement should encourage more companies to develop DTx for the Japanese market. From an investment perspective, Japan offers a relatively clear path: regulatory approval through the PMDA, then health insurance listing if efficacy and cost merits are shown.

The challenge is that the standards are high (the equivalent of drug-level evidence). But with two reimbursed DTx already generating revenue and more in the pipeline, Japan demonstrates that digital therapeutics can achieve both clinical credibility and commercial viability under a public payer.

South Korea: Laying Groundwork for Reimbursement

South Korea has quickly followed Japan’s lead in the regulatory space and is on the cusp of implementing DTx reimbursement. In February 2023, South Korea’s Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) approved the country’s first digital therapeutic, an insomnia treatment app called Somzz (by Aimmed). This marked the beginning of what Korean officials call the “era of digital therapeutics”. The MFDS had proactively issued guidelines for DTx clinical trials and evaluation, which helped accelerate this approval. Somzz is a prescription CBT-I app for chronic insomnia, similar in concept to the SUSMED app in Japan. Its approval was a significant milestone, and Korean regulators signaled that several other DTx (for substance use, depression, etc.) are in clinical trials and expected to follow (jkms.org).

On the reimbursement front, South Korea is actively developing a pathway. Under Korea’s national health insurance, new treatments typically undergo Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) for coverage decisions, akin to drug reimbursement evaluation. The government has indicated that MFDS-approved DTx “can expect to receive national health insurance reimbursement” but must go through similar procedures and criteria as drugs or devices. There isn’t yet a dedicated fast-track law (like Germany’s DVG) in Korea. However, there are existing mechanisms that might be leveraged. For example, Korea has a designation for “innovative medical devices” that allows selective (limited) use in practice for 3–5 years prior to full reimbursement.

This is somewhat analogous to Germany’s temporary listing. A DTx deemed innovative could be provided to patients as a non-reimbursed or partially reimbursed service for a few years while data accumulates, and then HIRA would decide on permanent reimbursement based on that evidence. Authorities have explicitly considered adopting a system similar to DiGA, where doctors could prescribe listed DTx and insurers cover them for a trial period without complete evidence yet.

As of July 2025, no DTx has fully passed through Korea’s reimbursement process, but Somzz and potentially others are in the assessment phase.

Meanwhile, the first mover company in Korea’s DTx space, WELT Corp., has achieved an encouraging milestone. WELT (which partnered in developing Somzz) announced that its insomnia digital therapeutic is now reimbursed in South Korea for patients, becoming one of the first software treatments to be covered by the national system (een.ec.europa.eu). This reimbursement appears to be within a specific program or pilot rather than broad coverage for all patients yet. Specifically, Korea’s National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency has been studying DTx, and it’s likely that WELT’s app got provisional reimbursement as an innovative treatment.

The Enterprise Europe Network report confirms that WELT’s insomnia DTx, proven effective in trials, “has been approved for reimbursement in South Korea” which now allows the company to reach a broader patient base. This suggests that by mid-2024, South Korea did implement a reimbursement decision for at least that one product – a strong signal that the system is moving. It’s worth noting that reimbursement in Korea often comes with conditions (e.g. coverage only for certain patient criteria, or for a set number of therapy weeks, etc.) and with negotiated pricing.

We do not yet have public info on the price Korea will pay for the insomnia DTx, but it will likely be scrutinized for cost-effectiveness against alternatives (like sedative medications or therapist-led CBT-I).

South Korean payers (National Health Insurance Service) are likely weighing the need to foster a domestic DTx industry (Korea has a booming digital health startup scene) against the budget impact. The domestic market potential is significant – Korea’s digital therapeutics market is projected to quadruple from 2019 to 2025 (from ~₩125 billion to ₩529 billion, approx $400M). For investors, Korea is an attractive emerging DTx market: the government has signaled support via fast regulatory approvals, and now the first reimbursement deals are happening.

However, coverage is not automatic; each DTx will need to prove itself. One challenge is cultural and clinical integration – Korean doctors and patients need to get accustomed to software prescriptions. The medical community is currently discussing how to incorporate DTx into practice (e.g. will hospitals prescribe apps directly? will pharmacists be involved in dispensing activation codes? etc.). The outcome of Somzz’s rollout will be closely watched. If it shows good patient uptake and clinical outcomes under reimbursement, it will pave the way for depression, addiction, or diabetes DTx in Korea’s pipeline.

Emerging Interest in Other Asian Markets

Outside of Japan and Korea, most Asian countries are at earlier stages regarding DTx reimbursement, but interest is growing:

China

China has a massive digital health and mobile app usage, yet no formal reimbursement pathway for digital therapeutics exists as of 2025 (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The Chinese healthcare payment system (largely public insurance via the National Reimbursement Drug List, NRDL) has not incorporated DTx, and there are no established assessment criteria for such products. In practice, digital health solutions in China are often provided through private channels – for example, via employer wellness programs, direct-to-consumer sales, or bundled with services at internet hospitals. In some advanced regions (like Beijing, Shanghai), local authorities have experimented with including telehealth or digital management programs for chronic disease in their coverage, but these are ad-hoc.

For instance, a province might subsidize a diabetes management app for residents as part of a “Smart Health” initiative, but there is no nationwide coverage policy for DTx. Nonetheless, China has a vibrant DTx development scene (hundreds of clinical trials ongoing for digital interventions). We may see change in coming years: the government’s Healthy China 2030 plan emphasizes health tech, and if evidence from domestic DTx pilots (many of which are government-funded) shows cost savings, China could integrate DTx into their healthcare insurance. For now, investors should note that China is a huge user market for DTx (people willingly use apps, often paying out-of-pocket for programs like weight management or physical therapy apps), but the monetization often comes via private pay or hospital purchase rather than insurance reimbursement.

Singapore & Hong Kong

These healthcare systems are advanced and tech-friendly but have not yet set up specific DTx reimbursement schemes. Singapore’s public insurance (MediShield Life) typically covers hospitalizations and some outpatient treatments, and could theoretically cover digital therapeutics if classified under approved treatments. Singapore has been running digital health pilots, for example using a mobile app for hypertension monitoring in its public polyclinics. There is also the MOH Office for Healthcare Transformation which has trialed apps for diabetes. So far, funding for these comes from government innovation budgets, not the insurance fund. However, given Singapore’s drive for a “Smart Nation,” it wouldn’t be surprising if they eventually allow certain eHealth solutions to be claimable under insurance or employer medical benefits.

Hong Kong’s insurance is less centralized, but some private insurers in HK and other parts of Asia (e.g. in Thailand, Malaysia) have begun offering coverage for digital wellness programs as part of value-added services. This is not exactly reimbursement, but it indicates a trend where insurers see value in digital therapeutics to reduce claims costs (for example, an insurer might fully pay for a diabetes management app subscription for members, hoping it prevents costly complications).

Australia (broader Asia-Pacific)

Australia’s public Medicare system has not yet listed any DTx on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. However, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) has approved a few digital mental health apps as medical devices, and there are active discussions about funding them. Given Australia’s inclusion in many Asia-Pacific analyses, we note it here: Australia tends to follow evidence-based practice and might reimburse DTx that NICE or FDA have validated if local need exists (for example, an insomnia app could be covered under mental health services funding). The state of Victoria has piloted a digital rehab program for chronic pain, funded by the state health budget.

India and others

In much of South and Southeast Asia, public health insurance is limited or non-existent for novel therapies. Digital therapeutics in these markets are typically direct-to-consumer or sponsored by healthcare providers. For instance, in India, apps for managing hypertension or mental health are offered by startups on a subscription model to patients or via B2B deals with employers. The concept of reimbursement doesn’t strongly apply where out-of-pocket spending dominates. That said, some national programs (like India’s national digital health mission) might incorporate free digital self-management tools for the populace, but that is more a public health provision than an insurance reimbursement.

In sum, Asia (ex-Japan/Korea) is still one to watch in the DTx reimbursement realm. We see the most concrete progress in countries with mature healthcare financing: Japan leading with actual reimbursements, Korea close behind, and others slowly evaluating the landscape. Payer perspectives in Asia differ by system – Japan and Korea’s public insurers are conservative but open to innovation that tackles priority health issues (aging society, chronic disease). In emerging markets, payers (both public and private) are interested in the cost-saving potential of digital therapeutics, since these regions face shortages of healthcare professionals and high burdens of chronic illness. An effective DTx can scale care to thousands of patients without direct physician time, which is very attractive. The challenge for these markets will be building regulatory and assessment capacity to identify which DTx are truly effective and worth covering.

Payer Perspectives and Impact on Pricing of DTx

Across both Europe and Asia, one theme is clear: getting reimbursement right is crucial for digital therapeutics. The long-term success of DTx companies and the health outcomes for patients depend on aligning these products with payer incentives and healthcare budgets. Early experiences have yielded several insights into how payers view DTx, what concerns they have, and how pricing models are evolving:

Evidence, Evidence, Evidence

Payers universally demand robust evidence of clinical benefit. Unlike consumer wellness apps, prescription DTx are being held to medical standards. Germany’s GKV, for example, grew uneasy that it was paying tens of millions for apps with unproven outcomes – a situation they do not tolerate for drugs. This has led to moves toward outcomes-based payment (Germany’s upcoming rule that 20% of payment is outcome-dependent) and stricter initial thresholds (France’s HAS denying an app that wasn’t convincingly innovative). Payers often ask: does this digital therapy improve patient-important outcomes (e.g. HbA1c for diabetes, abstinence rate for smoking, symptom scores for mental health) compared to standard care? If the answer is not yet proven, payers tend to limit access (via provisional coverage or by negotiating lower risk-sharing prices).

The history so far shows that DTx firms must plan for rigorous clinical trials and real-world studies to satisfy payers’ evidence requirements. This is a shift from early days where some thought a cool app with basic validation could sail through. Now, even in fast-track schemes, the clock is ticking to demonstrate value or be delisted.

Cost-Effectiveness and Budget Impact

Particularly in Europe, payers are incorporating DTx into their health economic evaluations. They compare the app’s cost and efficacy to existing treatments. For instance, if a DTx for chronic back pain costs €600 and yields similar outcomes as €100 of painkillers and physiotherapy, insurers will balk. German SHI representatives explicitly noted that many DiGA prices seemed out of line with “the reimbursement of conventional medical care” and called for economic efficiency assessments.

In England, NICE will only recommend DTx that save money or are cost-effective under their QALY (quality-adjusted life year) thresholds, as they do for drugs. This means value-based pricing is becoming the norm for DTx: companies must price their products in accordance with the health benefit delivered. We are starting to see reference points – e.g. an insomnia DTx might be valued against the cost of 6 months of zolpidem (sleeping pills) plus therapy; a diabetes DTx against the cost savings from avoided complications. Investors should be prepared that payers will not grant high prices unless there is clear evidence of superior outcomes or offset of other medical costs.

Pricing Models – From One-Time Licenses to Subscription and Outcome-Based

Digital therapeutics enable innovative pricing models, and payers are exploring these. Traditional reimbursement pays per prescription or per unit. But for software, alternatives are possible: subscription models, pay-per-use, or milestone payments tied to patient engagement or outcomes. German insurers have shown interest in usage-based payments – e.g. only paying the full price if a patient actually activates and uses the app to a certain degree (healtheconomicsreview.biomedcentral.com).

This stems from data that in early DiGA usage, 20% of prescribed apps were never activated by patients, meaning money wasted if paid outright. Outcome-based models, as discussed, are on the horizon (pay X% only if patient’s health improves by a defined metric). Some DTx contracts (especially in the U.S. employer market) already use pay-for-outcome deals (e.g. diabetes app getting bonuses for each percentage of patients hitting glucose targets). In Europe’s public systems, this is newer but clearly coming (Germany being first). We also see talk of “rental” models – perhaps an insurer pays a monthly fee per user rather than a lump sum, allowing easy cessation if the app isn’t used or working. In summary, payers want to share the risk.

They are wary of upfront high costs for digital therapies that might not be utilized or effective. So, the pricing paradigm for DTx is shifting to performance-based arrangements, which is different from how drugs are paid (though even drugs are moving toward outcomes-based deals in some cases).

Managing “Digital Inflation”

One of the payer fears is that covering hundreds of apps could balloon healthcare costs without commensurate benefit – a “digital inflation” of health expenditures. The German GKV report frankly noted the quarter-billion euro spend in 4 years and questioned the return on that investment. Insurers do see potential for cost savings with DTx in the long run (for example, preventing hospitalizations or reducing medication use). But they are determined to prevent a scenario where they reimburse a flood of apps that incrementally help a little (or not at all) and collectively drain funds. Therefore, payers are clamping down on which DTx get reimbursed and for how long.

We see this in the high bar set by France’s HAS and the culling of underperforming apps in Germany. From an industry standpoint, this is a double-edged sword: it means fewer, better DTx will make it through, which could concentrate market share in those who have the evidence and can prove ROI to health systems. Payers will likely favor DTx that target high-cost conditions (to maximize potential savings) such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, mental health (especially where untreated cases lead to costly outcomes). If a digital therapeutic can clearly reduce expensive events (e.g. a CHF monitoring app preventing readmissions), payers will support it. If it only offers a mild convenience on top of existing care, payers will ask “is it worth paying for?” In essence, the reimbursement game is about demonstrating true value-add.

Effect on DTx Prices

The experience to date shows a trend: initial prices have often been cut significantly under payer pressure. In Germany, as noted, negotiated prices ended up ~50% lower than initial manufacturer prices on average (healtheconomicsreview.biomedcentral.com). In some cases, manufacturers might have priced high expecting to be knocked down; in others, they might have hoped to maintain a higher price but volume was lower than expected. Over time, if many competitive products exist for a similar indication (say 5 different mental health apps), payers could leverage competition to drive prices down, similar to how generics drive down drug prices.

However, with DTx the competition may be less direct since each is somewhat unique.

Another factor is sustainability of business models: if prices drop too low, DTx companies may struggle to recoup their development and maintenance costs, which can endanger the product’s future (an example being Pear Therapeutics in the U.S. facing financial woes in part due to reimbursement hurdles and pricing issues). Payers want a good deal, but they also acknowledge that if reimbursement is not adequate, innovation will stall. German stakeholders have expressed that pricing models should “not kill innovation” while insisting on fairness. We may see creative solutions like tiered pricing (maybe an insurer pays a base fee plus bonuses for outcomes), or government subsidies for DTx for rare conditions to ensure companies continue developing them.

Payer Involvement in Development

Another interesting dynamic is that some payers are directly investing in or co-developing DTx. In Asia, for instance, Japanese insurance companies (and even life insurers) have partnered with DTx startups to pilot solutions for their insured populations. This could lead to private reimbursement models outside the public system (e.g. a private insurer including a DTx as part of a policy benefits package). If these private experiments show positive results (like reduced claims), it could influence public payers to follow suit. Payers ultimately care about outcomes and costs, not the modality of treatment – so if digital proves it can do the job better or cheaper, payers will embrace it.

In summary, payer perspectives are evolving from initial curiosity to seasoned skepticism and now to a conditional optimism. Reimbursement models are adjusting: moving from open-door to guarded entry, from pay-and-pray to pay-for-performance. For the digital therapeutics sector, mastering the reimbursement piece is crucial. It’s not enough to build an effective product; one must navigate the healthcare system’s approval and pricing negotiations. Those who succeed will unlock large revenue streams and widespread patient access. Those who don’t align with payer needs may find themselves limited to small self-pay markets.

Conclusion: The Crucial Importance of Getting DTx Reimbursement Right

The journey of digital therapeutics reimbursement in Europe and Asia up to July 2025 reveals a fast-moving, learning process. Early trailblazers like Germany showed that it is feasible to bring digital treatments into mainstream healthcare and pay for them at scale – a revolutionary concept turning smartphones into reimbursable medicine. However, these experiences also underscored that reimbursement without robust value demonstration is unsustainable. Payers quickly adapted, tightening the rules to ensure digital therapeutics truly improve patient outcomes and justify their costs.

For healthcare investors and stakeholders, a few key takeaways emerge.

Market Access is Payer-Driven

No matter how innovative a DTx is, its commercial success in Europe or Asia hinges on navigating public reimbursement systems (or large private insurers). Understanding each country’s pathway – be it Germany’s DiGA, France’s PECAN, Japan’s MHLW approval, or Korea’s emerging process – is essential. Companies need strategies tailored to these models, including compiling evidence dossiers for HTA bodies and engaging early with payers to address their concerns (data privacy, integration, cost offset, etc.).

Reimbursement ≠ Automatic Uptake

Even with coverage, physician and patient adoption needs effort. Germany found that lack of physician awareness and workflow integration can hinder prescriptions. Thus, getting on the reimbursed list is only half the battle; driving utilization through education and ease-of-use is the next. From an investment view, one should evaluate whether a DTx company not only has reimbursement approval but also a plan to generate demand under that reimbursement.

Price and Revenue Expectations Should Be Calibrated

The era of naming an arbitrarily high price for a digital therapeutic and expecting payers to foot it is over (if it ever truly existed). Companies must be prepared for negotiations that may substantially cut their per-unit price. This is not necessarily detrimental if volume can compensate and if pricing is sustainable. Indeed, a lower price point that encourages broad coverage might yield higher total revenue and more patient impact than a high price that limits uptake. The focus is shifting to “recurring revenue through sustained outcomes” rather than one-time big payouts. Investors will likely favor DTx firms that demonstrate they can thrive under value-based contracts.

Global Diffusion of Models

We can anticipate cross-pollination of reimbursement models. Europe’s conditional coverage concept is being noticed in Asia (e.g. Korea considering a DiGA-like list). Likewise, Asia’s strict evidence-first approach (Japan) sends a message that some markets won’t compromise on clinical proof. Eventually, we might see more convergence – perhaps a de facto standard where a digital therapeutic goes through a provisional reimbursement for 6-12 months globally, and then needs to show real-world data for permanent reimbursement. For now, companies have to juggle different rules in different countries, but any success in one major market (say a DTx that secures permanent reimbursement in France with strong data) will bolster its case in others.

Did They Deliver on Promises?

It’s a mixed verdict so far. On one hand, we have real patients benefiting from DTx that they wouldn’t have access to otherwise – nearly a million uses in Germany, new treatment options in Japan, etc. There are anecdotal stories of patients whose lives improved thanks to these apps, validating the concept. On the other hand, the broad health economic promise (e.g. significantly reducing healthcare costs or significantly improving population health metrics) is not yet proven at scale. The next few years, with more outcome tracking, will tell us if digital therapeutics can bend the curve on certain diseases. Payers are hopeful but impatient on this front. If delivered, we can expect even more enthusiastic adoption; if not, some reimbursement programs might retrench.

In conclusion, proper reimbursement strategies are the linchpin for digital therapeutics’ success. For investors analyzing the space, it’s crucial to look at how well a DTx product is positioned in light of these models: Does it target a high-priority disease with clear measurable outcomes? Have its clinical benefits been demonstrated convincingly? Can it integrate into care pathways to actually be prescribed and used? And can it do all this in a cost-effective way that makes payers happy? The companies and products that check these boxes will likely become the winners in the digital health revolution, securing not only reimbursement but also the trust of physicians and patients.

Those that fall short may find themselves as interesting tech with limited reach. The history from 2019 to 2025 has been about establishing the playing field; the future will be about proving value on that field. Reimbursement is not just a financing mechanism – it is effectively becoming a quality filter and growth engine for the digital therapeutics industry. Getting it right means millions of people will gain access to cutting-edge therapies through their health systems, and that, ultimately, is the promise of digital health: to deliver better outcomes at scale, with payers as partners in innovation rather than obstacles.

Member discussion