Fund of the week: LifeArc

Overview and Financial Model

LifeArc is a UK-based medical research charity with a unique financial model, operating more like an investment fund backed by past drug royalties rather than through ongoing donations. The charity finances itself via a large endowment-like investment portfolio, seeded by monetizing a blockbuster drug royalty. In 2019, LifeArc received $1.297 billion by selling a portion of its royalty interest in Merck’s cancer immunotherapy Keytruda (pembrolizumab).

This was on top of an earlier partial sale in 2016 for $150 million. These one-time inflows made LifeArc “one of the UK’s leading medical research charities by size of investment assets” (biopharmadive.com).

As a result, LifeArc is self-funded and does “not rely on fundraising or external grants” for its operations (lifearc.org).

Today, LifeArc’s investment portfolio stands at ~£1.25 billion (as of Dec 2024), generating income to fund its research and investment activities. The portfolio is managed for long-term growth, targeting annual returns of inflation +3.5% (lifearc.org) through a diversified mix of global equities, fixed-income, private assets, real estate, and hedge funds.

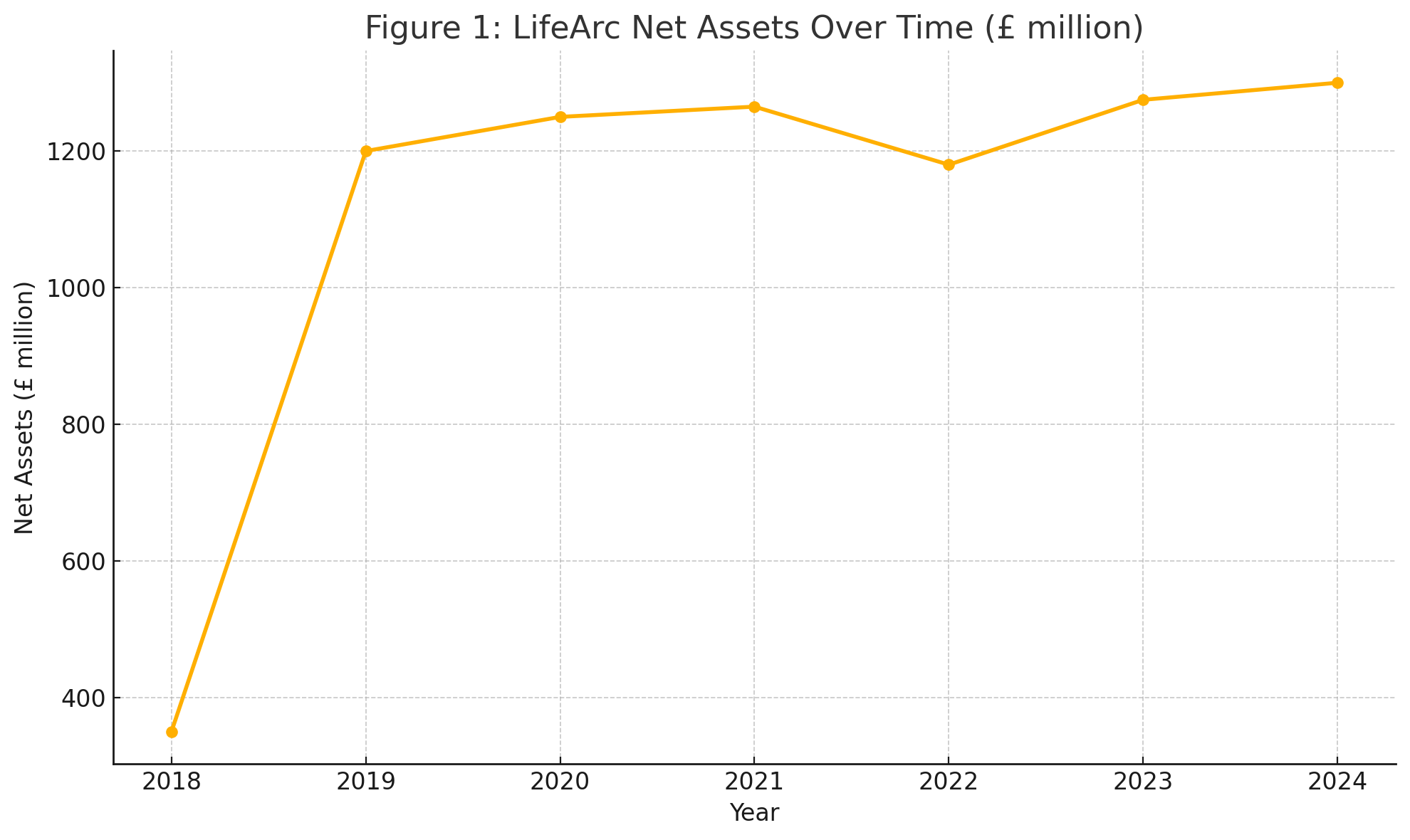

This strategy is intended to preserve and grow the endowment to sustain LifeArc’s mission. Figure 1 shows how LifeArc’s net assets jumped after the Keytruda royalty monetization and have fluctuated with market conditions and spending in recent years.

Figure 1: LifeArc net assets (funds) at year-end. A major one-time royalty sale in 2019 boosted assets to ~£1.2 billion. Since then, prudent investment returns and spending led to modest growth, with a dip in 2022 (market downturn) and a rebound in 2023 (royalty income + market gains).

Revenue Sources: LifeArc’s income comes primarily from (1) returns on the investment portfolio, and (2) life-science royalties or milestone payments from past research, with some additional service fees. By policy, investment returns (interest, dividends, capital gains) are all reinvested into funding new research programs.

LifeArc also still receives “income from service agreements, royalties, and milestones” on partnered projects (lifearc.org), though these were relatively minor until a recent spike (discussed below). Importantly, LifeArc’s model means it can deploy funding without needing to raise capital from donors or limited partners each cycle, giving it a stable financial footing insulated from external fundraising markets.

Royalty Income and Performance

LifeArc’s royalty income is heavily linked to the success of Keytruda, the PD-1 cancer therapy that its predecessor organization helped develop by humanizing the antibody. In fact, as of 2019 “contract and royalty revenue still primarily comes from Keytruda” (biopharmadive.com).

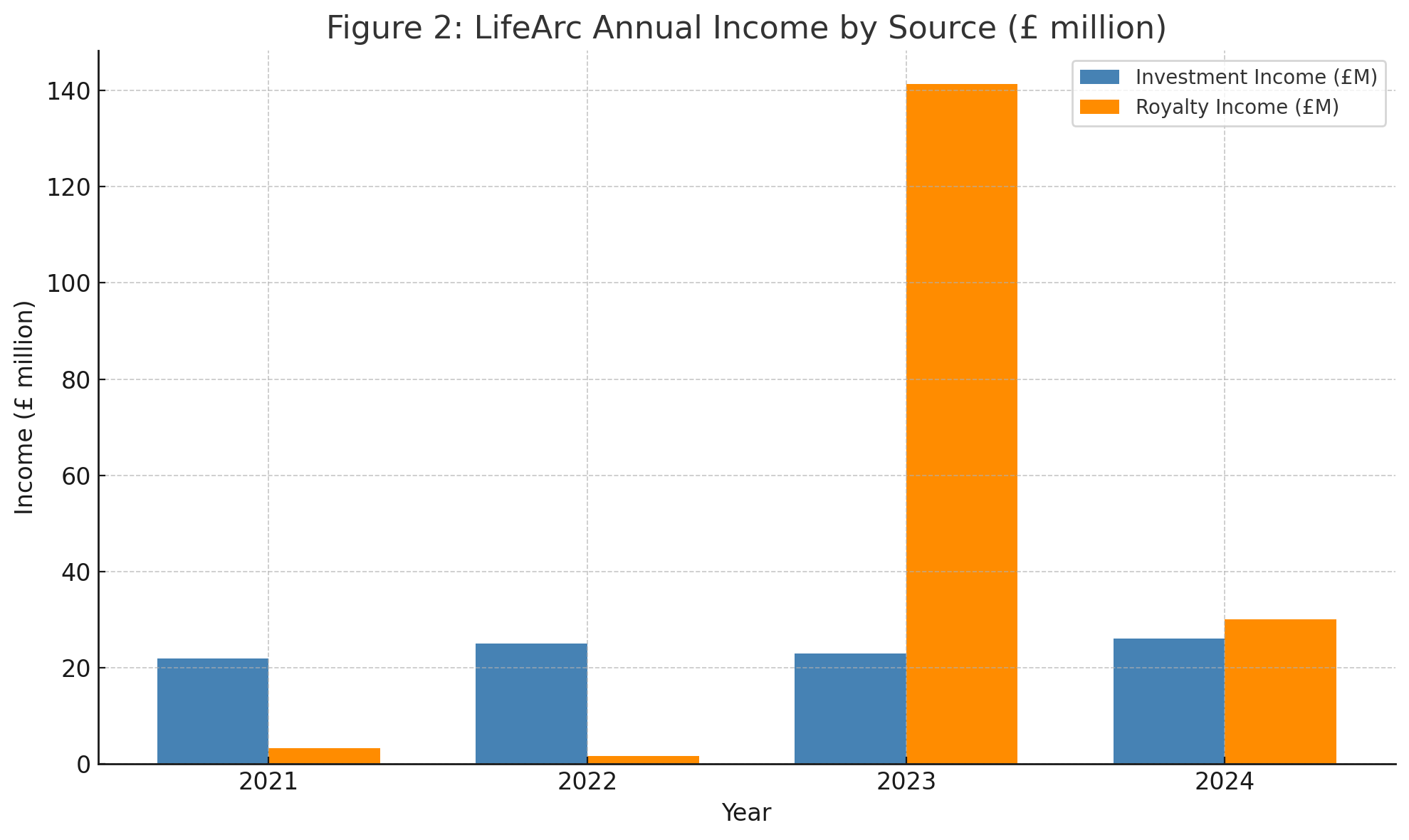

he 2016 and 2019 royalty monetizations converted much of this future income into upfront cash. However, LifeArc retained some interest and other royalty streams, which led to a surge in royalty income in 2023: LifeArc’s latest accounts show £141.3 million in contract/royalty income for 2023, versus only ~£1.7–3.3 million in each of 2021–2022.

This enormous jump (see Figure 2) suggests a one-time realization – likely either a further monetization of remaining Keytruda rights or a major milestone payment/license deal. Keytruda became the world’s top-selling drug by 2023, so any royalty share would have ballooned correspondingly. Indeed, Merck’s Keytruda sales ($20+ billion in 2023) translated into substantial royalties; LifeArc’s accounts imply it recognized that value in 2023.

Aside from Keytruda, LifeArc has modest royalty contributions from other drugs it helped develop (e.g. autoimmune drugs Actemra, Tysabri, Entyvio in past collaborations), but none on the scale of Keytruda.

Figure 2: LifeArc annual income by source. Investment income (blue) has been steady, reflecting returns on the £1.2–1.3B portfolio. By contrast, royalty and contract income (orange) was minimal (~£2–3M) in 2021–2022, then spiked above £140M in 2023 due to a major royalty monetization or license deal.

Going forward, LifeArc’s reliance on Keytruda revenues is a key strategic consideration. The charity proactively diversified its finances by selling royalty rights (as noted in the CPPIB deal) to reduce over-reliance on a single asset. Its investment portfolio now provides a more predictable income stream (~£20–25M/year), and LifeArc is cultivating new revenue sources – for example, it secured rights to royalties from Eisai/Biogen’s Alzheimer’s antibody lecanemab (Leqembi) after contributing to its early development. If Leqembi and other partnered programs succeed, they could form future royalty streams.

Nonetheless, as of 2025, Keytruda royalties (direct or monetized) remain the dominant financial resource, which is both a strength (high cash influx) and a risk (concentration) discussed later.

Deals and Investments (2022–2025)

Over the past three years, LifeArc has deployed its capital through a mix of equity investments, non-dilutive grants, and collaborative funding partnerships. The organization straddles two roles: an investor (via its LifeArc Ventures arm) and a philanthropic funder of translational science. Below is a detailed look at major deals from 2022 through mid-2025, illustrating LifeArc’s activities:

Venture Investments (Equity Deals)

LifeArc Ventures focuses on early-stage biotech and healthtech companies (Seed to Series A), aiming for financial return and patient impact. The portfolio expanded from 14 companies in 2022 to 17 by end-2024. Despite a broader market downturn in biotech financing, LifeArc continued investing actively each year. For example, in 2023 it added six new startups, including leading a $16 million Series A for Cambridge-based Maxion Therapeutics (ion-channel drugs), co-founding a new UK company targeting Huntington’s disease, and backing U.S. digital therapeutics firm Affect Therapeutics in its $16M round (lifearc.org).

In 2024, LifeArc made three new investments, notably joining a $27 million Series A for Canadian medtech Fluid Biomed Inc. (brain aneurysm stent) and two stealth-stage biotech deals (one in AI-driven drug discovery, one in autoimmune therapeutics). Earlier, in 2022, the Ventures team had also expanded into healthtech with an investment in Surgery Hero (a digital surgery-prehab platform) and co-founded RQ Bio – a monoclonal antibody spinout. RQ Bio achieved a high-profile success in May 2022 by licensing its COVID-19 antibody to AstraZeneca in a deal worth up to $157 million plus royalties.

LifeArc’s role was pivotal: “LifeArc had the vision to co-found and support RQ Bio from the very beginning… both as major shareholder and scientific partner”, enabling rapid progress to clinic (lifearcventures.com). This model – founding a company around internal/external science and quickly partnering with pharma – exemplifies LifeArc’s niche.LifeArc Ventures has also seen notable exits: Two portfolio companies were acquired in 2022 – DJS Antibodies (bought by AbbVie for $255 M) and Ducentis BioTherapeutics (bought by Arcutis for up to $400 M).

And in late 2024, its digital health investee Surgery Hero was acquired by a U.S. firm (Sword Health)lifearc.org. These exits validate LifeArc’s ability to pick promising science and realize returns. Importantly, all investment gains are recycled into the charity’s fund for future research.

LifeArc often co-invests alongside traditional VCs (e.g. it led Tribune Therapeutics’ €37 M Series A in 2025 with Novo Holdings and others), and it reserves capital for follow-on rounds to support its companies’ growth. In 2024, for instance, LifeArc provided follow-on funding to Affect Therapeutics and to gene therapy startup Ikarovec.

By the start of 2025 the venture portfolio spanned diverse areas (gene therapy, antibodies, digital health, etc.), including standouts like AviadoBio (gene therapy for FTD dementia) which signed a licensing option with Astellas worth up to $2.18 B in milestones, and Pheno Therapeutics (MS remyelination therapy) which entered clinical trials with support from UCB. These indicate potential future upside if LifeArc’s equity stakes appreciate.

Non-Dilutive Grants & Co-Funded Programs

A large portion of LifeArc’s deal flow is in grant-making and translational funding partnerships, aligning with its charitable mission. LifeArc launched several high-impact funding initiatives in the period:

Motor Neuron Disease (MND) Challenge

In 2023 LifeArc committed £5 million to an international call for repurposing existing drugs for MN (Dlifearc.org). It also co-funded (£500k) a UCL research team (with the MND Association and My Name’5 Doddie Foundation), whose gene therapy work later attracted a £76M venture investment (Trace Neuroscience, 2024). These illustrate LifeArc’s catalytic role – providing early funds that de-risk projects and help leverage much larger outside investments.

Neurodegeneration (Dementia)

Through a £30M partnership with the UK Dementia Research Institute, LifeArc awarded £14.5 M to 7 new dementia research projects in 2023. It also helped launch NEURii, a collaboration with Gates Ventures, Eisai, and others to develop digital tools for dementia care (lifearc.org).

Rare Disease Translational Centres

In 2023–24 LifeArc undertook its largest grant initiative to date – a £40 million program to establish 4–5 Translational Rare Disease Centres across the UK. By April 2024, four centers were selected, each a multi-institution consortium tackling a cluster of rare conditions. For example, the new LifeArc Centre for Rare Respiratory Diseases (led by University of Edinburgh) was awarded £9.4 M to create a national hub connecting patients, biobanks, and researchers for rare lung diseases.

Another center for rare kidney diseases received £10.4 M (co-funded with Kidney Research UK contributing £1 M).

These centers aim to “speed up delivery of rare disease trials” by overcoming the fragmentation in rare disease research (lifearc.org). This strategic spend positions LifeArc at the forefront of rare disease translation infrastructure.

Global Health & Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

LifeArc made several commitments under its Global Health challenge. In 2023 it co-founded the Pathways to Antimicrobial Clinical Efficacy (PACE) initiative – a £30 M partnership with Innovate UK and Medicines Discovery Catapult – to accelerate antibiotic innovation for AMR threats. In 2024, LifeArc became a founding partner of the Fleming Fund Initiative at Imperial College, pledging £25 M to this £100M global program to combat AMR, alongside GSK and others.

Additionally, LifeArc invested £2.7 M into a new infectious disease innovation fund with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s iiCON consortium (announced Dec 2024) to boost novel diagnostics and trials. These moves not only provide funding but leverage LifeArc’s “expertise in drug discovery and IP management” in global collaborations (lifearc.org).

Supporting African R&D

Partnering with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, LifeArc is investing £6 M (jointly) in the Grand Challenges African Drug Discovery Accelerator (GCADDA) to fund drug discovery projects in sub-Saharan Africa. Launched in early 2024, this program supports five African-led research projects (targeting diseases like malaria and TB) and aims to strengthen local scientific capacity (lifearc.org). LifeArc also put £7.5M into the Crick Africa Network to train African biomedical researchers (funding 8 new fellows in 2024).

Other Notable Partnerships

LifeArc joined Britain’s massive health data initiative Our Future Health in 2024 as a charity partner with a £10 M commitment, focused on using the cohort’s data to advance dementia and other translational research. It also teamed up with the U.S. Cleveland Clinic in 2025 to co-develop new monoclonal antibody therapies for unmet needs (combining LifeArc’s antibody discovery know-how with Cleveland Clinic’s clinical insight).

Similarly, a partnership with Neuropeutics Inc. (a biotech in ALS/MND) was announced in 2025 to jointly advance a promising therapeutic for motor neuron disease These collaborations extend LifeArc’s reach globally and bring external expertise to its projects.

In summary, LifeArc deployed substantial capital in 2022–2025 via a balanced mix of investments and grants. It invested tens of millions into ~10+ early-stage companies (often syndicating with venture firms) and concurrently granted well over £100 M to translational research initiatives (rare diseases, neurodegeneration, AMR, etc.) in that period. This dual approach – investing for returns on one hand while funding non-profit research on the other – is what makes LifeArc unusual in the life sciences ecosystem.

Approach to Biotech Investing and Partnerships

LifeArc’s approach to biotech investing is distinct from a traditional venture capital (VC) firm and also from typical research charities, effectively blending elements of both:

Non-Dilutive vs Equity Funding

LifeArc uses both grant funding and equity investment as tools. Early academic or translational projects often receive non-dilutive grants (e.g. its Pathfinder awards, challenge calls) to hit key milestones. When projects mature or spin out, LifeArc can follow up with equity investment through LifeArc Ventures. This staged support means LifeArc sometimes seeds a project as a charity and later becomes a shareholder if a company is formed. An example is RQ Bio: initially co-funded as a mission to develop COVID antibodies, then structured as a company in which LifeArc took equity and helped secure a lucrative pharma license (lifearcventures.com).

Compared to pure VCs, LifeArc is more willing to fund early high-risk science with grants (since financial return isn’t required at that stage), effectively de-risking projects for the ecosystem. But unlike a traditional charity, LifeArc will take equity when it believes that will ultimately yield returns that can sustain its mission. All equity returns or licensing revenue are plowed back into its charitable work, not paid out to any owners.

Partnerships and Collaboration

By mandate, LifeArc works very collaboratively. It often co-funds programs with other charities, government agencies, or industry, providing matching funds and expertise. This is a differentiator from many VCs that might avoid multi-party grants or complex public-private setups. LifeArc’s partnership with Innovate UK and a national lab on the PACE antibiotic initiative is a case in point; or its co-funding of a rare kidney disease center with Kidney Research UK. Such arrangements leverage LifeArc’s money to unlock equal or greater contributions from others. LifeArc also brings in its in-house scientific teams and labs to collaborate on projects – a value-add that VCs typically do not offer.

The Ventures team has access to LifeArc’s drug discovery labs in Stevenage and Edinburgh and a roster of internal scientists, which they use to diligencing opportunities and to support portfolio companies’ research. This is closer to an incubator or corporate VC model (where technical support is provided), but here it’s under a charity umbrella.

Mission and Return Expectations

LifeArc explicitly seeks a “dual goal of generating financial returns … and positive impact for patients”. This mission-aligned stance differentiates it from pure-profit investors. LifeArc will invest in areas of high medical need (e.g. antimicrobials, rare diseases, neurodegeneration) that many VCs consider too risky or with unclear commercial returns. Success is measured not only in ROI, but in whether new treatments reach patients. That said, LifeArc still exercises financial discipline: it has an Investment Committee with seasoned VC experts (including former SR One partners) to vet venture deals, and it aims to “generate financial returns by investing in innovative early-stage companies” to keep funding its charitable activities (lifearc.org).

In practice, LifeArc often syndicates with mainstream investors on market terms – for example, joining rounds led by well-known VCs like General Catalyst and BGF for Maxion’s Series A, or partnering with Novo and HealthCap on Tribune’s financing. It does not seek concessionary terms; any “patient capital” advantage comes from its ability to invest long-term without needing to exit under typical fund timelines.

Overlap and Differences with Traditional VCs

LifeArc Ventures functions similarly to a venture fund (sourcing deals, doing due diligence, taking board observer seats, etc.), but unlike a VC it doesn’t have external LPs demanding returns or a fixed fund lifespan. There is no management fee or carry – the team are charity employees and returns flow back into LifeArc’s pool. This structure gives LifeArc more patience and flexibility in holding investments (they can wait longer for an optimal exit and can invest in tougher areas where quick returns aren’t assured).

It also means LifeArc can be more mission-driven in selection, focusing on translational potential over purely maximizing IRR. On the other hand, LifeArc overlaps with research charities/foundations in providing grants and focusing on patient impact, yet it differentiates itself by having significant in-house investment capabilities and a mandate to earn returns. Few charities directly invest in startups the way LifeArc does.

In essence, LifeArc fills a niche between academia, charity, and venture capital – sometimes described as a “self-funded translational accelerator.” It works alongside academic tech transfer offices (indeed, LifeArc originated as the MRC’s tech transfer arm) but now also partners with pharma and venture investors as an equal. This gives it a broad perspective: it can fund early discovery like a philanthropy, and ride the venture growth curve like an investor.

Bull vs Bear Case for LifeArc’s Model

From an investor or limited partner standpoint, LifeArc presents both compelling strengths and potential concerns given its hybrid model:

Bull Case (Opportunities & Strengths)

LifeArc’s mission-aligned capital and structure offer some clear advantages. It provides “patient, insulation-from-market” funding – with a £1.3B endowment, LifeArc can continue investing steadily even during biotech market downturns, without needing to raise new fund. This was evident in 2022–2023 when many VCs pulled back, yet LifeArc kept deploying capital (six new deals in 2023 despite “challenging financing conditions”). Its investments are not tied to a 10-year fund clock, allowing portfolio companies a longer runway to achieve scientific milestones rather than rushing to exit. Moreover, LifeArc’s capital is “mission-driven but not dumb” – it seeks returns, which imposes financial rigor, but will back important medical areas that align with its mission even if they are out of favor cyclically (e.g. investing in antimicrobials or CNS diseases that generalist VCs often avoid).

This mission lock can attract co-investors and partners who value the non-financial impact; LifeArc effectively crowds in others by de-risking science with grants and by signaling validation (its involvement in a biotech can lend credibility due to its scientific heft). Another bull point is non-dilutive leverage: LifeArc’s grant funding to companies or academic groups can significantly boost a project’s value without diluting equity, which ultimately benefits all shareholders (including LifeArc if it’s also an investor). For instance, when LifeArc funds an academic to do proof-of-concept work and then a startup forms, that startup can command a higher valuation and attract top-tier VCs – a win-win for impact and return.

LifeArc’s internal scientific expertise is also a strength; portfolio companies get access to “hands-on support… strategic advice and lab facilities”, which can increase their chances of success. Finally, LifeArc’s secure financial base means it is insulated from short-term pressure: it doesn’t have to exit positions at an inopportune time or chase trendy areas just to appease investors – it can be disciplined and long-term in funding decisions.

All of these factors suggest LifeArc could achieve “venture-like returns with mission-aligned resilience,” making it an attractive collaborator for both investors and researchers.

Bear Case (Risks & Challenges)

Critics might argue that LifeArc’s model faces limitations in return potential and agility. First, its financial success is highly dependent on a single historical revenue source – Keytruda – which is a finite asset. While monetizations yielded a huge endowment, those funds must last; if LifeArc cannot regenerate similar value from new royalties or investments, its spending could deplete the endowment over time. The heavy concentration in one royalty stream historically (over 90% of LifeArc’s income has come from Keytruda) underscores this reliance. Second, many of LifeArc’s outlays do not generate direct returns: large grants (e.g. the £40M Rare Centres, £25M Fleming AMR fund) are essentially expenditures for public good, not investments that will come back as profits. This could dampen overall portfolio returns compared to a pure-play VC – a significant portion of the “portfolio” is mission spending with zero financial return (albeit high social return).

Even on the venture side, LifeArc prioritizes early-stage and high-risk domains; the flipside of patient, impact-driven investing is that some bets may never pay off (e.g. antibiotics or neurodegeneration startups have historically low ROI in venture). There’s also the question of deal flow and quality: LifeArc is a newcomer in venture investing (ramping up only after 2019), so it lacks a long track record. It must compete with experienced VC firms for the best deals and talent – and while it can co-invest, it may not always get allocations in the hottest deals if not perceived as purely financially driven. Internally, as a charity, LifeArc might have more bureaucratic constraints than a nimble VC – investment decisions may go through multiple committees (e.g. scientific panels for grants, then an investment committee for equity), potentially slowing down the process.

LifeArc also has to balance dual mandates, which could lead to strategic dilution: for example, tension between funding certain projects for impact versus maximizing returns elsewhere. Its broad focus (from rare diseases to global health) could stretch management attention and lead to strategic concentration risk if too much money goes into one area that underperforms. Additionally, being a charity, LifeArc’s team incentives differ from venture partnerships – there’s no carried interest, which could impact the drive to maximize returns (though staff are undoubtedly mission-motivated). Finally, as a quasi-public charity handling a large fund, governance and public scrutiny can impose caution. Decisions might err on the side of caution or consensus, possibly missing out on bold moves a more aggressive investor might take.

In short, the bull case for LifeArc is that it represents a new model of “evergreen” biotech capital: financially self-sustaining, able to invest through cycles, and uniquely positioned to combine philanthropy and profit motives to capture outsized opportunities that align with its mission. Its recent exits and partnerships show promise that it can achieve both returns and impact.

The bear case, however, questions whether a charity-investor hybrid can truly compete with top venture funds in generating returns, given its need to devote resources to non-profit aims and its reliance on a past windfall. LifeArc’s future success likely hinges on smart stewardship of its endowment and the ability to recycle a few big wins (like the Keytruda royalty) into new breakthrough ventures or royalties.

Conclusion

LifeArc’s last three years have been marked by ambitious funding initiatives and a growing venture portfolio, all underpinned by the one-off fortune of Keytruda. The organization has carved out a distinct role in the biotech ecosystem – sitting at the intersection of charity and venture capital. It acts with the patience and purpose of a research foundation, yet thinks about sustainability and returns like an investor. For limited partners and biotech stakeholders, LifeArc offers a case study in how mission-driven capital can be deployed at scale: its bullish upside is the creation of a virtuous cycle where successful investments finance ever more impactful research, insulated from market vicissitudes.

Its downside risks lie in the challenges of straddling two worlds – the need to deliver both cures and financial self-reliance. As LifeArc moves forward, both the opportunities (e.g. leveraging its scientific platform, forging unique partnerships) and the challenges (maintaining returns, concentrating on what it does best) will shape whether it can truly fulfill the bold promise of its model. In an industry where funding and innovation are often at odds, LifeArc is attempting to bridge the gap – turning past scientific wins into future investment in science – and doing so with an analytical eye on returns and a steadfast focus on patients.

Member discussion