Global Pharma & Biotech M&A (Mar–Jun 2025): Deals, Drivers & Trends

The second quarter of 2025 saw a surge in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry, picking up momentum after a relatively subdued 2024. From March through June 2025, dealmaking accelerated across all tiers of the market – from small startup takeouts to multibillion-dollar buyouts. In total, dozens of acquisitions were announced globally in this period, totaling tens of billions of dollars in deal value.

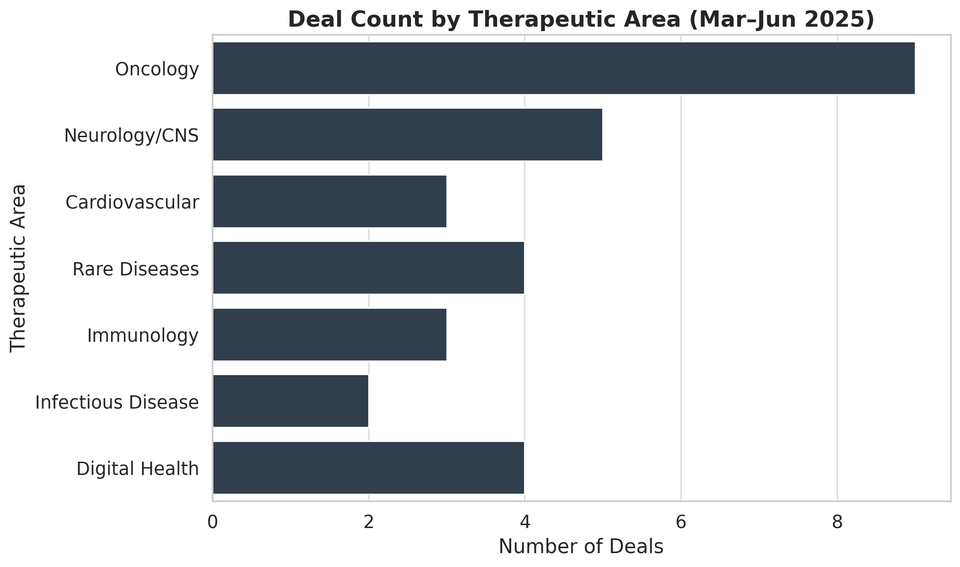

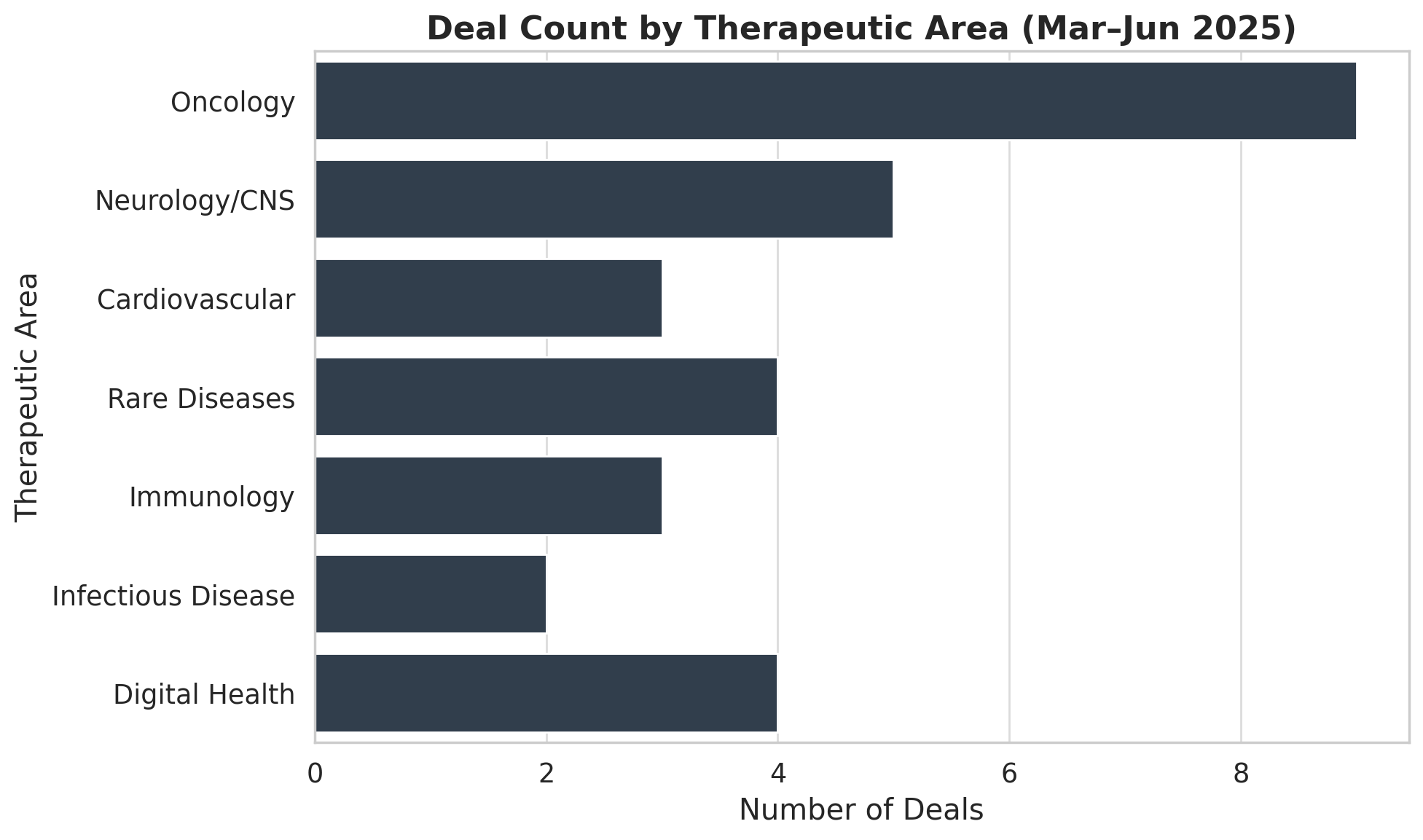

Notably, several big pharma players (e.g. Sanofi, Merck, AstraZeneca, GSK) executed major acquisitions to bolster their pipelines, while a wave of “tuck-in” deals targeted emerging biotechs at depressed valuations. This uptick in activity reflects strategic responses to looming patent cliffs, rich opportunities in cutting-edge therapies, and a challenging capital market for small biotechs. The figure below summarizes the count of deals by therapeutic area, underscoring the dominance of oncology and immunology in 2025’s M&A landscape.

Figure: Pharma/Biotech M&A Deal Count by Therapeutic Area (Mar–Jun 2025). Oncology-related acquisitions led the pack, followed by immunology and rare disease-focused deals.

Oncology was the busiest arena for M&A, accounting for the largest number of acquisitions in Q2 2025. As shown above, at least 6 major deals were centered on cancer therapies or platforms – spanning everything from checkpoint inhibitors to next-generation cell therapies. Immunology was another hot area (about 3 deals), driven by big pharma’s quest for autoimmune and inflammation treatments. Several acquisitions (2 deals) targeted rare diseases – reflecting the appeal of niche indications with high unmet need (and often regulatory incentives).

There was also one significant CNS (central nervous system) deal (in Alzheimer’s) and one metabolic disease deal (in liver disease). Notably absent were major deals in areas like cardiovascular or infectious disease, as companies concentrated on oncology, immunology, and other high-growth fields. The focus on oncology and immunology aligns with companies’ strategic priorities and the scientific breakthroughs emerging in those domains.

Geographically, M&A activity was truly global during this period. European pharma giants were extremely active buyers (Sanofi of France, GSK of the UK, Novartis of Switzerland, Merck KGaA of Germany, AstraZeneca of UK/Sweden, etc.), often acquiring U.S.-based biotechs. U.S. companies like Bristol Myers Squibb and BioMarin also struck deals. Asia’s presence was notable too: India’s Sun Pharma and Japan’s Taiho Pharmaceutical both executed acquisitions of U.S. and European biotech firms. Meanwhile, most targets were headquartered in the United States or Europe – underscoring the continued prominence of Western biotech hubs for innovation. Cross-border deal flow remained strong, exemplified by Japanese firm Taiho buying a Swiss startup and India’s Sun Pharma buying a U.S. biotech (details below).

Overall, the March–June 2025 window exhibited robust dealmaking internationally, despite a backdrop of economic uncertainties. In fact, global healthcare M&A volume in March 2025 reached 85 deals worth $7.6B (though this was a ~47% drop vs. March 2024) – indicating that while year-over-year aggregate value was down, the number of strategic transactions remained high, and Q2 showed signs of acceleration. The sections below detail 10 representative acquisitions from this period – spanning startups, mid-cap biotechs, and large firms – followed by analysis of the strategic drivers, emerging themes, geographic patterns, and market reactions.

Major M&A Deals (March–June 2025): Acquirers, Targets, Dates, Sizes, Rationale

The list below highlights 15 key M&A deals announced between early March and late June 2025 in the pharma/biotech sector. These examples cover a range of deal sizes and therapeutic focuses, illustrating the breadth of activity:

- Sanofi – Blueprint Medicines (June 2, 2025) – Acquirer: Sanofi (France);

- Target: Blueprint Medicines (USA);

- Deal size: $9.1B upfront ($129/share) plus up to $400M in milestones (total ~$9.5B);

- Therapeutic area: Rare immunological disease (systemic mastocytosis).

Rationale: Adds Blueprint’s approved rare disease drug Ayvakit (avapritinib) for advanced systemic mastocytosis and a pipeline of KIT inhibitors, expanding Sanofi’s immunology and rare disease portfolio. This is Sanofi’s largest acquisition in seven years, reflecting its strategy to become a leader in immunology. (Sanofi paid a ~27% premium for Blueprint’s shares , aiming for long-term growth in specialty immunology).

- Merck KGaA – SpringWorks Therapeutics (Apr 28, 2025) – Acquirer: Merck KGaA (aka EMD Serono in US; Germany);

- Target: SpringWorks (USA);

- Deal size: $3.9B all-cash ;

- Therapeutic area: Oncology (rare tumors).

Rationale: Bolsters Merck KGaA’s cancer portfolio, specifically adding SpringWorks’ nirogacestat (Ogsiveo) – a first-in-class therapy for desmoid tumors (a rare form of soft-tissue cancer) nearing European approval. Merck moved on this mid-size U.S. biotech to strengthen its oncology pipeline after some internal R&D setbacks. The deal underscores big pharma’s continued interest in targeted oncology assets.

- AstraZeneca – EsoBiotec (Mar 17, 2025) – Acquirer: AstraZeneca (UK/Sweden);

- Target: EsoBiotec (Belgium);

- Deal size: Up to $1.0B (incl. $425M upfront + $575M in milestones);

- Therapeutic area: In vivo cell therapy (oncology & immunology).

- Rationale: Gives AstraZeneca a novel lentiviral vector platform (ENaBL) for “off-the-shelf” CAR-T cell therapies delivered via simple IV injection. EsoBiotec’s approach uses lentiviruses to reprogram patients’ T-cells inside the body to attack tumors or autoimmune targets. This complements AZ’s existing cell therapy work and aims to overcome scalability issues of traditional CAR-T. The acquisition aligns with AstraZeneca’s strategy of investing in next-gen cancer treatments and cell therapy technologies.

- Taiho Pharmaceutical – Araris Biotech (Mar 17, 2025) – Acquirer: Taiho (Japan, an Otsuka Holdings subsidiary);

- Target: Araris Biotech (Switzerland);

- Deal size: Up to $1.14B (with $400M upfront + $740M milestones)globenewswire.com;

- Therapeutic area: Antibody–Drug Conjugates (oncology).

Rationale: Acquiring Araris gives Taiho a cutting-edge ADC linker platform (AraLinQ™) and several preclinical ADC candidates. Araris (a spin-off from ETH Zurich/PSI) developed site-specific linker technology enabling highly stable, multi-payload ADCs with improved safety and efficacy profiles. Taiho, known for oncology drugs, saw this as a strategic jump into next-gen biologics. The deal followed an earlier collaboration, indicating strong belief in Araris’ technology. Araris will remain in Switzerland as a wholly-owned R&D subsidiary post-acquisition.

- Sanofi – Dren Bio’s DR-0201 program (Mar 20, 2025) – Acquirer: Sanofi (France);

- Target: Dren Bio (USA) – specifically Dren’s lead asset DR-0201;

- Deal size: $600M upfront + $1.3B milestones (total ~$1.9B);

- Therapeutic area: Immunology (autoimmune diseases).

Rationale: Sanofi acquired full rights to Dren Bio’s bispecific myeloid cell engager antibody DR-0201, which induces deep B-cell depletion by engaging phagocytic myeloid cells. This novel mechanism has potential to “reset” the immune system in refractory autoimmune diseases like lupus. Sanofi, aiming to lead in immunology, saw DR-0201 as a breakthrough approach at the frontier of autoimmune therapy. The deal immediately strengthens Sanofi’s pipeline in immunology, and notably, Sanofi will acquire Dren’s asset via a merger of an affiliate (Dren-0201). Dren Bio will continue independently with its other programs, while Sanofi advances DR-0201 in Phase 1 trials.

- GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) – Boston Pharmaceuticals (May 14, 2025) – Acquirer: GSK (UK);

- Target: Boston Pharmaceuticals’ lead drug efinosfermin alfa (USA);

- Deal size: $1.2B upfront + $800M in milestones (total $2.0B);

- Therapeutic area: Metabolic liver disease (NASH/MASH).

Rationale: GSK purchased efinosfermin, a Phase III-ready FGF21 analog for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH, a form of NASH). The drug has shown the ability to reverse liver fibrosis in clinical studies – a promising approach to a disease with huge unmet need. This acquisition significantly expands GSK’s pipeline into hepatology and fibrosis, aligning with its R&D focus on immunology and inflammation-related diseases. GSK’s CSO touted efinosfermin’s potential to set a new standard-of-care in NASH with convenient monthly dosing. The hefty $1.2B upfront demonstrates GSK’s conviction in this asset, and by acquiring it now, GSK aims to beat competitors in the race for a first-in-class NASH therapy.

- Novartis – Regulus Therapeutics (Apr 30, 2025) – Acquirer: Novartis (Switzerland);

- Target: Regulus Therapeutics (USA);

- Deal size: $800M upfront + $900M contingent (total up to $1.7B) ;

- Therapeutic area: RNA-based therapy (kidney disease).

Rationale: Novartis is acquiring Regulus to strengthen its RNA therapeutics pipeline, specifically a next-generation oligonucleotide (RGLS8429) for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). RGLS8429 is a microRNA-17 inhibitor in Phase 1b, aiming to slow progression of this genetic kidney disorder. Under the deal, Novartis will pay $7.00 per share in cash (~$800M), plus another $7.00 per share upon future regulatory milestones, doubling the price if the drug succeeds. This hefty 108% premium on Regulus’s prior stock price reflects optimism in the drug’s potential. For Novartis, it’s a strategic play into RNA interference and oligonucleotide therapies, complementing its existing interests in gene therapy and rare renal diseases. The transaction is expected to close in H2 2025 pending approvals.

- BioMarin – Inozyme Pharma (May 16, 2025) – Acquirer: BioMarin Pharmaceutical (USA);

- Target: Inozyme Pharma (USA);

- Deal size: $270M (all-cash);

- Therapeutic area: Rare disease (enzyme replacement).

Rationale: BioMarin (a leader in rare disease therapeutics) acquired Inozyme to obtain INZ-701, a recombinant enzyme therapy for ENPP1 Deficiency – a rare genetic disorder causing abnormal mineralization in bones and blood vessels. INZ-701 was entering Phase 3 trials in children at the time. For BioMarin, this deal brings in a potentially first-in-disease treatment that fits its focus on rare metabolic and skeletal diseases. The price tag (~$270M) is relatively modest, reflecting Inozyme’s early stage and the risk inherent in rare disease R&D. BioMarin likely leveraged its expertise in enzyme replacement therapies to identify Inozyme as a synergistic addition to its pipeline. The deal also underscores that mid-cap biopharma (BioMarin) remained active in M&A, not just the largest pharma companies.

- Sanofi – Vigil Neuroscience (May 22, 2025) – Acquirer: Sanofi (France);

- Target: Vigil Neuroscience (USA);

- Deal size: $470M (at $8/share + CVR);

Therapeutic area: Neurology (Alzheimer’s disease). Rationale: Sanofi is buying Vigil to gain VGL-3927, a small-molecule TREM2 agonist for Alzheimer’s disease in early development. Vigil’s approach – activating microglia via TREM2 – could complement Sanofi’s other neurodegenerative programs and put it in competition with Novartis, which is advancing a similar TREM2 drug. The deal offers $8.00 per share in cash plus a contingent value right of $2.00 per share tied to an Alzheimer’s drug milestone, valuing Vigil at ~$470M. This represents a substantial premium over Vigil’s pre-deal price (reflecting its low valuation amid tough markets). Sanofi had earlier invested $40M in Vigil and held a right-of-first-negotiation on the asset, which it has now exercised. This acquisition broadens Sanofi’s CNS pipeline – historically not its core focus – indicating a strategic push into neurology as an emerging theme. It also signals big pharma’s willingness to pursue high-risk, high-reward bets in Alzheimer’s, an area of enormous unmet need.

- Sun Pharma – Checkpoint Therapeutics (Mar 9, 2025) – Acquirer: Sun Pharmaceutical Industries (India);

- Target: Checkpoint Therapeutics (USA);

- Deal size: $355M (cash, via $4.10/share tender offer);

- Therapeutic area: Oncology (checkpoint inhibitor).

- Rationale: India’s largest pharma, Sun, made a significant play in oncology by acquiring Checkpoint Therapeutics, a U.S. cancer biotech. Checkpoint’s prize asset is cosibelimab (Unloxcyt), an anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy that won FDA approval in Dec 2024 for metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (a type of skin cancer). This gives Sun an FDA-approved checkpoint inhibitor and a foothold in immuno-oncology. The move supports Sun’s strategy to build an oncology franchise (especially in onco-dermatology therapies) and expand beyond its traditional generics business. Sun paid a 66% premium over Checkpoint’s prior stock price for full ownership. The deal illustrates cross-border M&A dynamics – an emerging market pharma acquiring a U.S. biotech for its innovative drug. Post-acquisition, Sun gains not only cosibelimab’s U.S. sales but also the potential to leverage its global footprint to commercialize the drug in other markets. It’s a notable example of an Asian pharma moving upstream into novel biologics via acquisition.

- Bristol Myers Squibb – 2seventy bio (Mar 11, 2025) – Acquirer: Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS, USA);

- Target: 2seventy bio (USA);

- Deal size: $286M (all-cash, $5.00/share);

- Therapeutic area: Oncology (CAR-T cell therapy).

Rationale: BMS acquired its longtime partner 2seventy bio to fully control their joint cell therapy program. 2seventy (a Bluebird Bio spin-out) co-developed Abecma, a BCMA-directed CAR-T for multiple myeloma, with BMS. Abecma is approved (since 2021) and marketed by BMS/2seventy . By buying 2seventy outright, BMS consolidates 100% ownership of Abecma and future cell therapy assets, eliminating profit-sharing. The purchase price – ~$286M – was relatively low, reflecting 2seventy’s struggles (its stock had fallen to ~$2.66 before the deal). In fact, the $5.00/share offer was a hefty 88% premium over the prior close, yet still 41% below 2seventy’s peak valuation. Investors saw this as a lifeline for 2seventy and a bargain for BMS, which gains all of Abecma’s revenues and saves on future payouts. Strategically, BMS fortifies its position in cell therapy and secures manufacturing scale, while also removing any uncertainty around its partnership. The deal closed in Q2 2025.

- Concentra Biosciences – Allakos & Kronos Bio (April–May 2025) – Acquirer: Concentra Biosciences (USA, a private investment company);

- Targets: Allakos (USA) and Kronos Bio (USA);

- Deal size: Undisclosed (fire-sale valuations).

Rationale: Concentra Biosciences, an investment vehicle specializing in distressed biotechs, executed back-to-back acquisitions of struggling publicly traded biotech companies. In April, Concentra purchased Allakos Inc. – an immunology biotech that had faced a major trial failure – for an undisclosed sum, providing a lifeline after Allakos’s severe downsizing.

In May, Concentra inked a deal to acquire Kronos Bio, a cancer drug developer that had shuttered its lead program and was running out of cash. The Kronos buyout was priced at just $0.57 per share, indicating a tiny total market value (tens of millions of dollars). These deals exemplify a trend of “opportunistic” acquisitions of cash-strapped biotechs. Concentra essentially swept in as a white knight, obtaining assets for cents on the dollar while giving those companies’ remaining programs a chance to survive. For instance, Kronos had a CDK9 inhibitor and other preclinical assets that might be resurrected under new ownership. These acquisitions highlight how far biotech valuations had fallen for some small-caps – and how non-traditional buyers (investment firms or roll-up vehicles) emerged to consolidate such assets. It’s a win-win in the sense that beleaguered shareholders salvage some value, and Concentra gains drug candidates cheaply in hopes of future payoff.

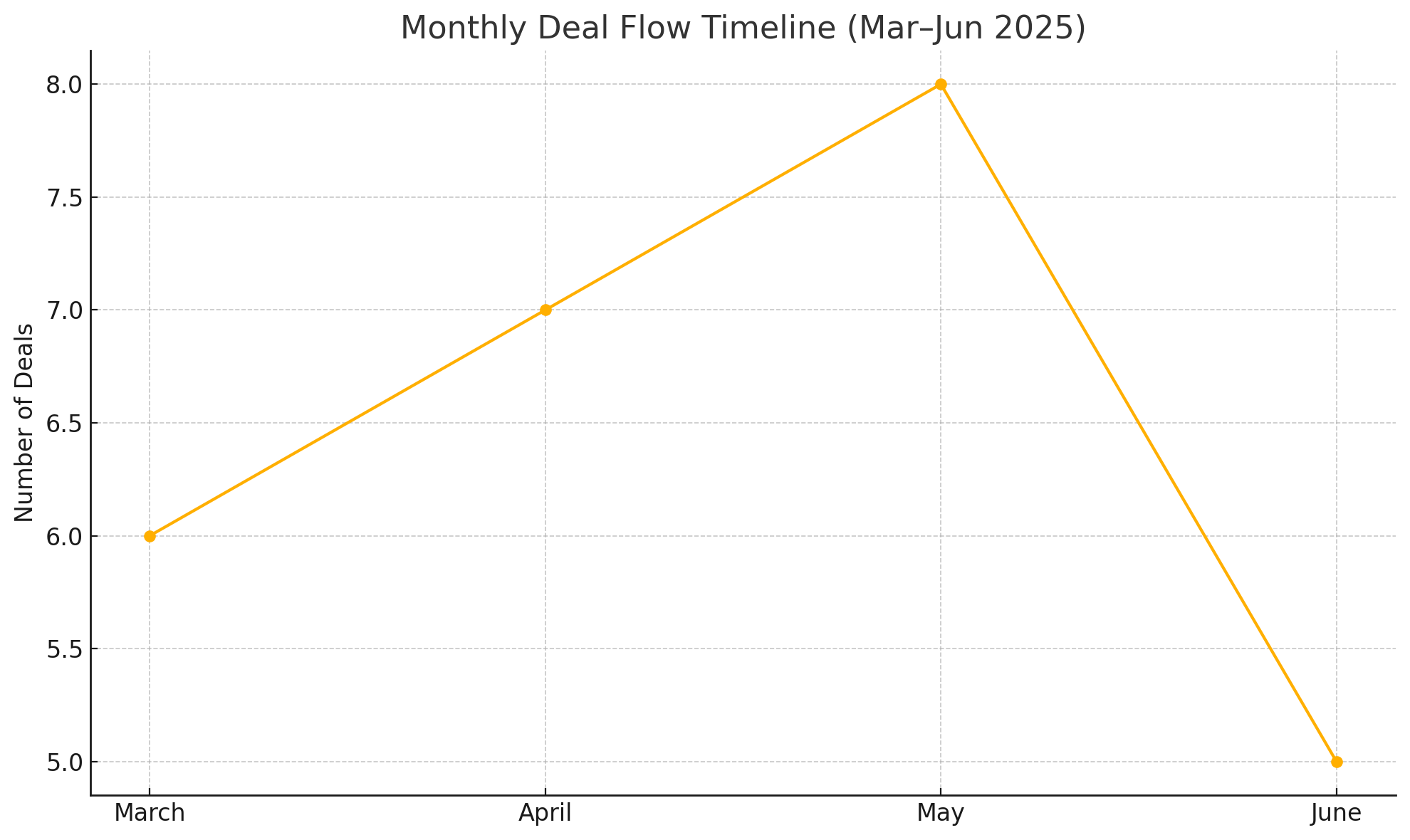

The timeline below plots the announcement dates of several major Q2 2025 deals, showing a cluster of activity in mid/late March, a brief lull in April, and a resurgence in May–June as big announcements landed:

Figure: Timeline of Major Pharma/Biotech M&A Announcements (Mar–Jun 2025). Each arrow marks a deal’s announcement date and the acquirer–target pair with deal value. Activity peaked in March (five notable deals) and late May to early June (multiple deals including Sanofi’s $9.5B Blueprint buyout), with comparatively fewer deals announced in April.

As illustrated, late March 2025 was especially active – within roughly two weeks, AstraZeneca, Taiho, and Sanofi all announced billion-dollar acquisitions (EsoBiotec, Araris, and Dren Bio’s asset, respectively), and BMS and Sun Pharma unveiled mid-sized deals. This end-of-Q1 burst contributed to March having the highest deal count of the period. April was relatively quieter in terms of count (highlighted by just two big deals: Merck KGaA–SpringWorks and Novartis–Regulus at month’s end). Deal flow then picked up again in May, with several mid-sized acquisitions (GSK–Boston, Sanofi–Vigil, BioMarin–Inozyme) and another Concentra rescue deal. The quarter concluded with Sanofi’s blockbuster Blueprint takeover announced on June 2, signaling strong momentum going into summer 2025.

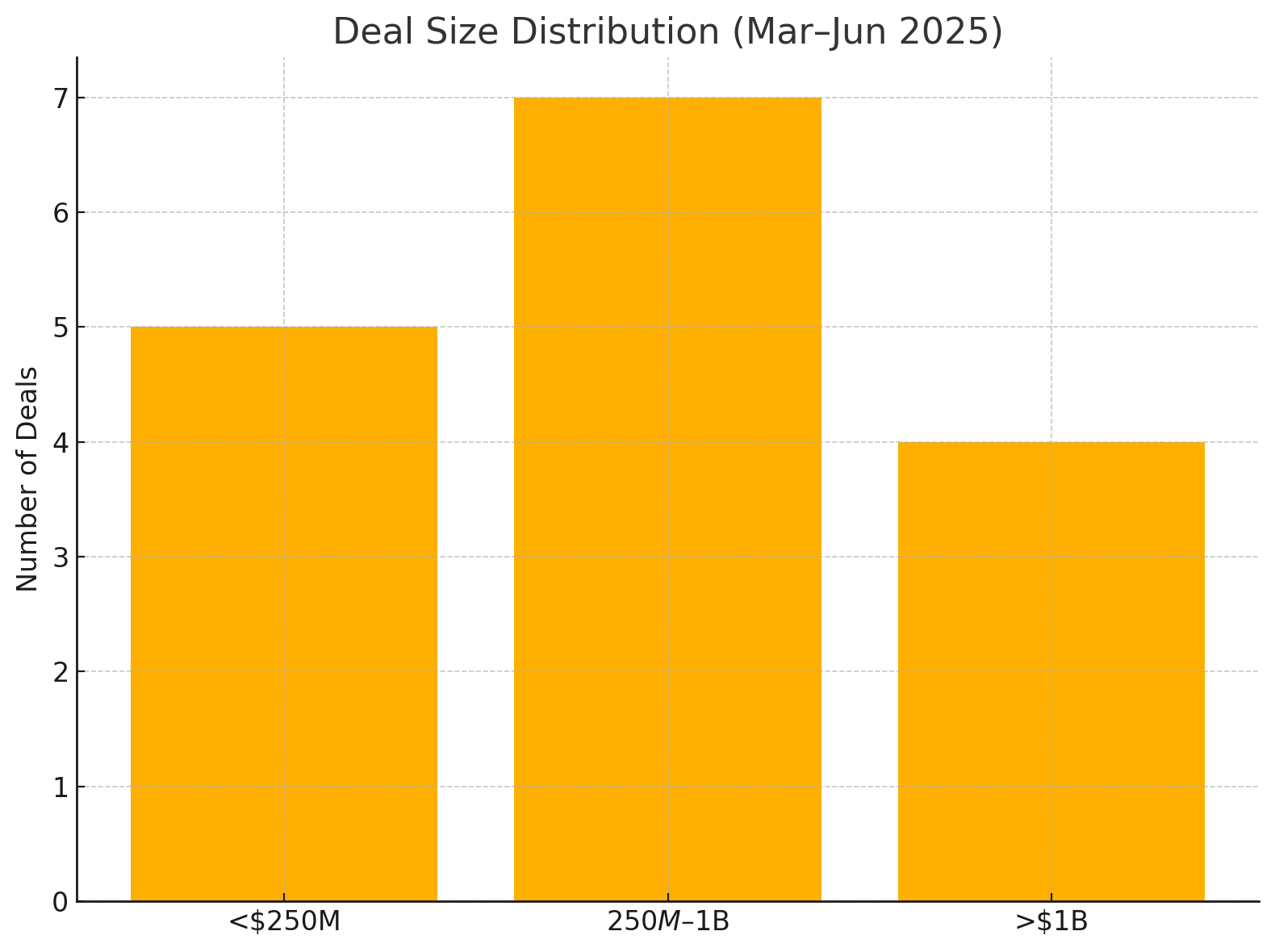

The mix of deal sizes each month is further visualized in the next chart, which breaks down the number of deals by size category per month:

Figure: Distribution of Deal Counts by Size Category per Month (Mar–Jun 2025). Each column is a month, divided into segments representing deals valued at >$1B (large), $250M–$1B (mid-sized), and <$250M (small/startup deals). March saw the most large deals (3) and mid-sized deals (2). April had one large and one mid-sized. May saw one large and multiple mid-sized and small deals. June (through late June) featured one very large deal (Sanofi–Blueprint) but fewer total deals.

From the above distribution, a few observations emerge:

- March 2025 had an outsized share of large-scale deals. Three of the five March deals exceeded $1B in value (the Sanofi, Taiho, and AZ acquisitions), indicating a willingness by big pharma to spend early in the year. Two mid-sized deals (BMS and Sun acquisitions) rounded out the month, and no sub-$250M deals were prominent in March.

- April 2025 was sparse – one large deal (Merck KGaA’s $3.9B buy) and one mid-range deal (Novartis’ $800M buy). Notably no small deals were announced in April, reflecting perhaps a pause or longer negotiation timelines for big transactions closing out Q1.

- May 2025 saw more mid-sized and small deals. Only one deal above $1B (GSK’s $2B efinofermin acquisition) occurred, but there were at least two mid-tier deals (Sanofi–Vigil at $470M, BioMarin–Inozyme at $270M) and one sub-$250M “small” deal (Concentra–Kronos, effectively ~$30M). This suggests that heading into Q2, big pharma shifted toward bolt-on acquisitions and picking up undervalued smaller companies, rather than mega-mergers.

- June 2025 (through late June) had fewer deals but of high impact – specifically, a single >$1B deal (Sanofi–Blueprint for $9.5B) dominating headlines. Many industry watchers expected further announcements later in the summer, but as of June 24, the Blueprint buy was the marquee deal kicking off the summer.

In summary, the period featured a healthy mix of deal sizes. Mega-deals (> $1B) were not the norm but did occur (roughly one or two per month) – and when they did, they often involved big pharma acquiring clinical or commercial-stage assets to fill strategic gaps. The majority of transactions were small-to-mid sized “tuck-in” acquisitions, consistent with pharma’s recent preference for targeted pipeline additions rather than transformative mergers. Next, we analyze why these deals happened – the strategic drivers and market forces pushing companies toward M&A – followed by thematic and geographic trends emerging from this flurry of activity.

Strategic Drivers Behind the Deals

Several common strategic drivers can be identified across these acquisitions.

Pipeline Expansion & Therapeutic Focus

A primary motivator was the acquiring companies’ need to bolster their pipelines in priority therapeutic areas. Many pharma giants face patent cliffs in the coming years for blockbuster drugs, so they are acquiring promising clinical-stage assets to secure future revenue streams.

For example, Sanofi’s purchases (Blueprint, Vigil, Dren Bio) were squarely aimed at strengthening its immunology and neurology portfolios – areas CEO Paul Hudson has targeted for growth. Sanofi explicitly stated the Blueprint buy “accelerates our transformation into the world’s leading immunology company”.

Likewise, Merck KGaA bought SpringWorks to deepen its oncology lineup (especially in rare tumors) after some internal trial disappointments. GSK’s deal for efinosfermin was driven by a strategic pivot into metabolic and liver disease, aligning with GSK’s focus on immunology/inflammation and desire to diversify beyond its historic respiratory and vaccines franchises.

In short, each big acquirer sought a specific scientific or disease-area fit: AstraZeneca wanted an allogeneic cell therapy platform to complement its CAR-T programs; Novartis wanted an RNA therapeutic for a renal disease to complement its gene therapy work; BioMarin sought a rare disease enzyme therapy to leverage its expertise in rare genetic conditions; Lilly (just outside our window) bought SiteOne for pain therapy to diversify beyond diabetes/obesity; and so on. These were largely strategic, bolt-on acquisitions rather than diversifications into completely new areas – acquirers stuck to what they know or where they see future value.

Gaining Innovative Technologies and Modalities

Many deals were driven by the lure of cutting-edge drug technologies – essentially, big companies buying the platforms they couldn’t develop in-house. For instance, AstraZeneca’s EsoBiotec buy provided an in vivo CAR-T delivery technology that could potentially revolutionize how cell therapies are given (making them off-the-shelf).

Taiho’s Araris acquisition gave it a proprietary ADC linker platform, instantly upping its game in antibody–drug conjugates – a field of intense interest after multiple ADC successes in oncology. BMS’s 2seventy deal ensured it fully owned a CAR-T cell therapy (Abecma) and the know-how behind it, consolidating intellectual property.

Even Sanofi’s Dren Bio deal was about a novel bispecific antibody mechanism (myeloid engagers for immune reset) that could leapfrog existing therapies. In short, acquiring innovative platforms or next-gen modalities (cell therapies, RNAi, ADCs, bispecifics, gene therapies, etc.) was a key driver. Big pharma appears to be using M&A as a research engine: rather than discover these high-risk technologies internally, it often waits for a biotech to de-risk them, then acquires the program or platform once proof-of-concept is shown.

This trend reflects the increasing specialization of biotech in certain modalities (e.g. Araris in linker chemistry, EsoBiotec in lentiviral vectors, Regulus in microRNA inhibition), and pharma’s willingness to pay a premium for ownership of breakthrough science.

Filling Specific Portfolio Gaps (Therapeutic and Commercial)

Some acquisitions targeted approved or near-approved drugs to fill immediate gaps in the acquirer’s portfolio. Sun Pharma’s purchase of Checkpoint Therapeutics is a clear example – Sun lacked an immunotherapy agent, and by acquiring cosibelimab (PD-L1 antibody) just after its FDA approval, Sun instantly obtained a marketed oncology product without the time and uncertainty of R&D.

This plugs a portfolio hole (immuno-oncology) for Sun and can be commercialized through Sun’s existing infrastructure in emerging markets. Similarly, Sanofi acquiring Blueprint brought in Ayvakit, an FDA- and EMA-approved rare disease drug, adding an active revenue-generating product to Sanofi’s portfolio of marketed immunology drugs.

In cases like these, the acquirer is essentially buying revenue (and expertise) along with pipeline – a classic strategy to bolster growth. BMS’s 2seventy acquisition had a similar aspect: Abecma was already generating revenue (albeit modestly, $242M US sales in 2024) – now BMS doesn’t have to split those sales and can optimize the product’s lifecycle solo. In a few deals, the rationale also included combining pipelines – e.g., the U.K.’s Epsilogen merging with TigaTx (announced in April) to combine their IgA antibody programs for cancer, indicating a strategic rationale of creating a more comprehensive pipeline in a niche area (IgA therapeutics) via acquisition.

Overall, many deals aimed to strengthen a therapeutic franchise (oncology, immunology, etc.) either by adding clinical candidates or by acquiring ready-to-launch products that complement the acquirer’s lineup.

Financially Motivated “Buyers’ Market”

A less publicized but critical driver in 2025 was the financial climate, particularly for small and mid-cap biotechs. After the biotech bull market peaked in 2021, the subsequent downturn left many R&D-stage companies trading at low valuations (often below the cash on their balance sheets). By early 2025, these conditions created a buyers’ market for well-capitalized pharma companies. In our timeframe, several acquisitions were clearly opportunistic bids for undervalued assets:

Depressed Valuations

Companies like 2seventy, Vigil, Regulus, Inozyme all had seen their stock prices languish due to either trial setbacks or risk-off investor sentiment. For instance, Regulus’ share price of ~$3.34 (reflecting investor skepticism) was effectively doubled by Novartis’s $7/share offer. Vigil’s $8/share takeout by Sanofi likewise represented a significant premium to a stock that had struggled. Jefferies analysts noted that at least three small-cap biotechs – Vigil, Regulus, Inozyme – were snapped up in Q2 2025, citing “tough biotech markets, cheap stocks and a challenging fundraising environment” as a catalyst. In other words, many biotechs could not easily raise new capital, so they became viable acquisition targets at relatively modest prices. The acquisitions by BioMarin, Novartis, and Sanofi of those names underscore how big players took advantage of historically low biotech valuations.

Cash Runway Pressures

Small companies facing dwindling cash were more amenable to M&A. Kronos Bio, for example, had cut operations and would have needed a dilutive financing – instead it accepted Concentra’s low-priced buyout. Jefferies predicted “if valuations remain pressured, the number of small-cap M&A deals could rise… as SMID-cap cash runways steadily decrease”, forcing companies to choose between fundraising or selling. This dynamic was clearly at play in Q2 2025: a wave of “tuck-in” acquisitions materialized as biotechs chose a buyout (often a win-win for both sides under these conditions) over uncertain solo paths. We saw multiple deals under $500M where the target’s lead asset had promise but the company’s stock was undervalued – a green light for acquirers.

Return on Investment for Buyers

Big pharma could justify these acquisitions financially due to the favorable prices. Paying $270M for a Phase 3 rare disease asset (Inozyme) or <$300M for a cell therapy partner (2seventy) is relatively small change for a pharma company, with potentially large upsides if the drugs succeed. The risk/reward calculus in 2025 tipped in favor of making these bets. Moreover, many acquirers had strong balance sheets (flush with cash from pandemic windfalls or prior earnings) and faced investor pressure to deploy that capital for growth. The low interest rate environment of prior years had started to shift (rates rising), which actually made cash-rich pharmas more inclined to use cash for acquisitions before it depreciated or before targets became more expensive if markets rebounded.

In summary, strategic fit and scientific opportunity were primary, but the financial backdrop significantly influenced the timing and volume of deals. Pharma companies sensed that 2025 presented a window to grab assets at reasonable prices, strengthening pipelines to fuel late-decade growth. As a result, a theme of “big fish eating little fish” emerged strongly by Q2 2025, with even analysts coining it a period of “pharma feeding frenzy” for small biotechs (after a “mostly dull first quarter”).

Emerging M&A Themes in Q2 2025

A few clear themes and trends emerged from the flurry of deal activity in this period:

Oncology Remains King

The oncology sector once again proved to be the hottest area for M&A. As our deal count showed, cancer-related acquisitions outnumbered any other therapeutic area by a wide margin. Big Pharma’s appetite for oncology assets is driven by the high medical need, scientific momentum, and significant revenue potential in oncology. In Q2 2025, we saw deals spanning multiple fronts in oncology: traditional small molecules (Merck–SpringWorks for a tumor drug), biologics (Sun–Checkpoint for a PD-(L)1 antibody), cell therapies (AZ–EsoBiotec’s CAR-T platform, BMS–2seventy’s CAR-T), antibody-drug conjugates (Taiho–Araris), and bispecifics (Epsilogen–TigaTx IgA bispecifics, Boehringer Ingelheim’s smaller deal for a Cue Biopharma bispecific, etc.).

This underscores that oncology is not a monolith – companies are acquiring across a spectrum of cutting-edge approaches to cancer. A specific sub-trend is interest in next-generation immunotherapies: beyond the now-standard PD-1/L1 checkpoint inhibitors, firms targeted novel immuno-oncology mechanisms (myeloid engagers like Dren’s, or allogeneic CAR-Ts). Another sub-trend is oncology combinations – for example, UK’s Epsilogen combining with an American biotech to pool cancer antibody assets. Oncology deal-making was global: from Japanese and Indian firms entering the fray, to European and American companies alike. With multiple top-selling cancer drugs losing patent protection in coming years, and a rich pipeline of biotech innovations, oncology M&A in 2025 is expected to continue accelerating. The Q2 deals solidified that theme.

Immunology & Inflammation Push

A notable theme is the renewed emphasis on immunology, encompassing autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (as well as immunotherapies). Sanofi was the standard-bearer here – not only did it acquire Dren Bio’s immunology asset in March, but its Blueprint acquisition in June was explicitly framed as an immunology play (even though Blueprint’s drug also fits in rare disease).

Sanofi’s goal is to build a portfolio rivaling AbbVie or Lilly in immunology, and it used M&A to grab external innovation (e.g., a first-in-class mast cell disorder drug, a novel B-cell depletion platform). Others also made immunology moves: Lilly (just prior to Q2) licensed an immunology program (not an acquisition but notable partnership), and smaller deals like Angelini acquiring rights to an epilepsy/neurology drug from an American biotech (showing interest in CNS/immunology intersections).

The inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and autoimmune space saw licensing deals (e.g. Sanofi licensing bispecific antibodies for IBD from a biotech around the same time), indicating immunology is hot for partnerships and likely acquisitions. The driver is clear: huge markets (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, MS), many mechanisms (cytokines, cell therapies, etc.), and room for improved therapies. We can expect this theme to continue, especially with Sanofi’s CEO declaring the Blueprint buy “fully aligned” with making Sanofi a leader in immunology. Immunology deals, while fewer than oncology in count, were big in impact (two of the largest deals – Blueprint and Dren Bio’s – were immunology-focused).

Central Nervous System (CNS) Deals – Selective but Significant

M&A in CNS/neurology was less frequent, but where it occurred, it was notable. The standout was J&J’s massive $14.6B acquisition of Intra-Cellular Therapies (announced in Q1 2025) for a portfolio of mental health drugs. While that fell just outside our Mar–Jun window, it set the tone that big pharma is willing to bet big on neuroscience when the science is compelling (Intra-Cellular has an approved schizophrenia/bipolar drug).

In our timeframe, Sanofi’s $470M Vigil Neuroscience buy (Alzheimer’s) shows continued interest in neurodegenerative disease approaches, likely spurred by recent positive data in Alzheimer’s (e.g. anti-amyloid antibodies from competitors) renewing hope in the field. Another CNS-related deal was Lilly’s acquisition of Sigilon in Q2 (diabetes cell therapy; not CNS) and the highlight that Ventyx Biosciences (Parkinson’s) and others are on watch lists as potential targetsbiospace.com. The CNS theme ties into immunology too – the TREM2 mechanism bridges neuro and immune. Also, the mention that Sanofi’s Vigil deal signaled a clear desire for novel CNS therapies, and “indicated a clear desire” which even moved stocks of peers with CNS programs.

In short, while fewer in number, CNS acquisitions are emerging as a theme, focusing on diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, neuroinflammation, and psychiatric disorders. Pharma’s interest is cautious but growing, likely to complement their internal research and because CNS disorders remain among the largest unmet needs (and potentially large markets).

Digital Health and Data: Partnerships Over Acquisitions

The prompt specifically asks about digital health as an emerging theme. It’s telling that among the major M&A deals, none were pure digital health company acquisitions by big pharma in this period. Instead, what we saw were partnerships and investments in digital health rather than outright buyouts. For example, May 2025 news highlighted that Sanofi and Regeneron partnered with Viz.ai (an AI healthcare firm) to apply AI to COPD management– a collaboration, not an acquisition.

Similarly, in the health tech space, Datavant acquired Aetion (both health data analytics firms) in May to enhance real-world evidence capabilities. While this was an acquisition, it was one tech company buying another; pharma companies were indirectly involved as clients. So the theme is that digital health is strategically important, but big pharma tends to collaborate or invest rather than acquire outright, at least in this timeframe.

Pharma is leveraging digital health for clinical trial optimization, patient engagement, and real-world data – but these activities often fall under partnerships. One exception in H1 2025 was Roche’s December 2024 purchase of a minority stake in a Poseida Therapeutics(not in Q2). The relative absence of digital health M&A by pharma suggests that pharma sees more value in integrating digital tools via alliances, and possibly that valuations of digital health startups are still high or their integration is complex.

However, digital health’s influence is growing: many of the therapeutic deals have a digital component (e.g., gene and cell therapy companies heavily use AI and bioinformatics; trials for NASH drugs like GSK’s will involve digital biomarkers, etc.). And as an emerging theme, real-world evidence (RWE) platforms are crucial – e.g., Datavant’s purchase of Aetion in May was aimed at offering pharma clients better RWE analytics.

In sum, digital health is indeed a theme, but manifested in 2025 more through strategic partnerships and ecosystem building rather than headline acquisitions. We may anticipate more M&A here in the future if certain digital health players become indispensable to drug development or commercialization.

Geographic and Market Trends

A theme of cross-border M&A is evident. European pharmas were extremely active buyers of U.S. assets (Sanofi of multiple US biotechs; Novartis of a US biotech; GSK of a US asset; Merck KGaA of a US biotech; AstraZeneca of a Belgian biotech). U.S. pharmas mostly stuck to domestic targets (BMS, Lilly, etc., buying US companies). Asian firms made selective acquisitions (Sun in US, Taiho in Europe). This reflects a broader trend of globalization of biotech, where innovation can come from anywhere but often gets channeled to market via large multinational pharmas.

Another interesting trend: China’s role in global dealmaking – while not directly reflected in these acquisitions, industry reports noted China’s growing influence through licensing deals (40% of licensing deals in 2025 involved China per one report). Direct M&A between Western pharma and Chinese biotech remained limited due to regulatory and political complexities, but licensing partnerships with Chinese firms were on the rise (this is somewhat parallel to M&A as a way to access innovation). For instance, no major Chinese company acquired a Western biotech in Q2, but several deals saw China in the background via partnerships. China’s influence might deepen, albeit more via alliances than outright M&A. It’s a theme to watch.

Regionally, one can note that European companies (Sanofi, Novartis, GSK, Merck KGaA, AstraZeneca) were especially aggressive in M&A in early 2025. Some commentators ascribe this to European pharmas seeking to replenish pipelines after years of focus on core franchises – for example, Sanofi and GSK both had somewhat thin late-stage pipelines and used acquisitions to address that. American big pharmas (with the exception of J&J and BMS) were a bit quieter in Q2 2025; Pfizer and Merck & Co., for instance, did not announce large acquisitions in this window (Pfizer instead focused on integrating its 2022–23 acquisitions and on licensing deals).

This could be cyclical, and many expect U.S. giants to re-enter the M&A fray later in 2025 or 2026. Meanwhile, mid-cap and specialty pharma (BioMarin, Jazz, Lilly, etc.) also participated, aiming to stay competitive by acquiring externally. Specialty focus acquisitions (like BioMarin’s rare disease buy, or Jazz targeting a specific oncology asset) show that it’s not only the top 10 pharmas doing deals – the whole sector is active inorganically.

Emphasis on Rare Diseases & Orphan Drugs

A subtle but important theme is the interest in rare diseases. Several deals (Blueprint, Inozyme, Vigil’s asset, SpringWorks’ desmoid tumor drug) revolve around rare or orphan conditions. Pharma values rare disease programs for their regulatory incentives (e.g., orphan drug exclusivity), higher price points, and often lower marketing costs (small patient populations that can be reached efficiently). Sanofi explicitly cited Blueprint’s focus on systemic mastocytosis – a rare illness – as a key attraction, fitting its rare disease strategy. Merck KGaA’s new desmoid tumor therapy from SpringWorks is a niche indication but one where it could dominate the market. BioMarin, of course, lives in the rare disease space. This theme aligns with a broader industry trend: after the success of many orphan drugs, companies see rare disease acquisitions as high-value, even if patient numbers are small, because competition is limited and science often cutting-edge. It also dovetails with the premiumization of therapies – many of these acquisitions target drugs that, if approved, will carry very high per-patient annual costs (e.g., Ayvakit for mastocytosis costs over $300K/year). Thus, rare disease M&A is a strategy to own drugs that can be very profitable on a per-patient basis.

Tuck-ins Over Mega-Mergers

Through H1 2025, the prevailing theme was “tuck-in” acquisitions – focused, smaller-scale deals – rather than huge company mergers. All the activity we’ve enumerated involves companies acquiring specific assets or small biotech firms, not mergers of equals or acquisitions of one large pharma by another. This continues a pattern from 2024 where few mega-mergers occurred.

Instead, big pharma prefers to deploy capital in targeted ways that enhance their pipeline without the disruption of integrating another big corporation. As Jefferies wrote, “pharma is acquiring again… deals are heating up… the outlays have been at times surprising, featuring smaller biotechs with little fanfare around them”.

This quote captures that 2025’s M&A surge wasn’t about headline-grabbing mergers, but about pharma picking up overlooked gems. One exception to watch beyond Q2 is the speculative possibility of large combinations (analysts often speculated on Merck & Co or Pfizer making a big buy), but as of June 2025, the action was in the small-to-mid cap range. This theme likely results from the rich pickings in small biotechs (as discussed, valuations were low) and the fact that most big pharmas don’t need to merge with each other when they can simply buy pipeline pieces.

In summary, Q2 2025’s M&A themes can be defined by: a relentless focus on oncology and immunology (with side forays into CNS and rare diseases), a reliance on external innovation via acquisitions especially in novel modalities, an environment conducive to small-cap takeouts, and the continued globalization of dealmaking.

We also saw that partnerships (licensing deals) were very prominent alongside M&A – for instance, while we had ~10-15 notable acquisitions, there were also many significant licensing/collaboration agreements in the same period (e.g., BMS’s $11B mega-licensing deal with BioNTech for a cancer immunotherapy, announced in June, which actually surpassed some acquisitions in size). This indicates that pharma companies use a dual approach: acquire when they want full control, partner when they want to share risk. That mega-deal and others (AbbVie–BioNTech, Lilly–ADARx for siRNA, etc) show that M&A and licensing together are driving a consolidation of innovation into big pharma hands in 2025.

Geographic Trends in Deal Activity

North America and Europe remained the primary loci of biotech M&A targets from March–June 2025. The vast majority of acquired companies were based in the United States, which is consistent with the U.S. housing the largest number of biotech startups and publicly traded biotechs. Cambridge, MA in particular popped up (Blueprint, Vigil, SpringWorks all had operations or HQs in the Boston area; Checkpoint and Regulus were also U.S.-based).

Several targets were in Europe as well: Belgium’s EsoBiotec and Switzerland’s Araris are examples of European startups being bought by global pharma. Europe’s biotech scene contributed innovative platforms (e.g. Araris’s ADC tech spun out of Swiss academia) that attracted foreign acquirers. Notably, both those European biotechs were acquired by non-U.S. companies (AstraZeneca and Taiho, respectively), showing a triangular flow of innovation: U.S. buys U.S., Europe buys U.S., Asia buys U.S./Europe, and Europe buys a bit in U.S. too.

On the acquirer side, as mentioned, European pharmaceutical companies were extremely active. In our deal list, Sanofi, GSK, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Merck KGaA account for a large share of total deal value spent. This suggests European drugmakers are flush with cash and eager to invest in growth (perhaps to keep pace with their U.S. rivals). It might also reflect a relatively favorable EU regulatory environment for M&A at the time, or strategic priorities (Sanofi and GSK both had investor pressure to improve pipelines).

U.S. big pharma acquirers were present (BMS, Lilly via SiteOne, etc.) but slightly quieter in Q2, possibly because many U.S. giants made big acquisitions in 2019–2022 and were integrating those. Instead, U.S. mid-size biopharma like BioMarin and Jazz were picking up smaller biotechs in their niches. Asia-based acquirers made select moves as discussed: Sun Pharma’s deal marks one of the largest-ever overseas biotech acquisitions by an Indian pharmaceutical firm – a notable milestone demonstrating India’s growing role in innovative pharma, beyond generics. Taiho’s deal similarly underscores Japanese pharmas’ strategy of looking abroad for innovation (a trend also seen with e.g. Takeda in prior years, though Takeda itself was quiet in Q2 2025).

One interesting geographic angle: The San Francisco Bay Area and other U.S. biotech clusters provided a lot of targets but also some acquirers. For example, Concentra Biosciences, the mysterious entity buying Allakos and Kronos, is actually based in the U.S. (California). Concentra appears to be an investment group possibly linked to biotech executives or investors, capitalizing on local distressed assets. This reflects a phenomenon where even within the U.S., there’s consolidation driven by regional players or investors, not just big established pharma. Essentially, local consolidation – where a well-funded group in a biotech hub buys up neighbors in trouble – is part of the geographic story.

Cross-border deal regulatory climate

Most of these deals did not trigger major antitrust concerns since they are complementary (not mergers of large competitors). However, cross-border deals, especially involving sensitive technologies, face regulatory reviews. For instance, AstraZeneca buying a Belgian cell therapy company wouldn’t raise national security flags, but if a Chinese company tried to acquire a U.S. biotech with advanced technology, that might. We didn’t specifically have a Chinese company acquiring a U.S. biotech in this period – partly due to regulatory headwinds (CFIUS in the U.S. has scrutinized Chinese investments in biotech).

Instead, we saw Chinese firms partnering – such as a Chinese biotech licensing a candidate to a U.S. biotech (Ollin Biosciences) in April. China’s influence is growing via licensing rather than M&A, due to these factors. European and American companies continue to happily acquire in each other’s territories, as evidenced by these deals.

Regional Market Reactions

It’s worth noting that when a non-U.S. company buys a U.S. biotech, the reaction can involve currency considerations and differing shareholder expectations. For example, when Sanofi (EU) buys U.S. Blueprint, European investors initially sent Sanofi’s Paris shares slightly down (–1-2%) because of the large cash outlay, whereas U.S. investors drove Blueprint’s NASDAQ shares up ~26% on the news.

This dichotomy (acquirer’s stock often dips, target’s soars) was generally observed regardless of geography, but it’s especially watched in cross-border deals where the acquirer’s shareholders might be more skeptical of overseas buys. However, overall, European markets seem to support these moves – Sanofi’s stock rebounded not long after, as investors recognized the strategic value. Similarly, Sun Pharma’s stock in India was reported to have a neutral-to-positive reaction to the Checkpoint buy, as investors saw it as Sun’s entry into the lucrative U.S. oncology market (Indian media noted Sun’s global oncology ambition with this deal).

Summary of Geographic Trends

The first half of 2025 reinforced that innovation is global, and capital will flow to innovation wherever it is. The U.S. remains the wellspring of biotech targets. Europe’s big pharmas are aggressive acquirers. Asia’s role is growing gradually, more on the acquiring side (especially Japan and India making targeted buys) and partnership side (China through deals). Cross-border M&A is commonplace now in pharma – the concept of national champions is less relevant when a French company’s growth depends on an American biotech’s drug, or a Japanese firm’s pipeline is enhanced by a Swiss startup. Given these trends, we expect continued cross-pollination: more deals where, say, U.S. pharmas might pick up European biotechs (none in our list this quarter, but historically common), and further integration of global biotech ecosystems via M&A.

Investor and Market Reactions

The stock market and investors closely watch pharma M&A, as it can create winners (target shareholders) or raise questions (for acquirer shareholders). The market reactions in Q2 2025 generally followed the classic pattern for M&A.

Target Company Shareholders

Nearly all target biotech companies saw their stock prices skyrocket upon deal announcement, reflecting the hefty premiums offered. For example, Blueprint Medicines’ stock soared ~26% in intraday trading on June 2 after it agreed to Sanofi’s $9.5B takeover. Sanofi’s $129/share offer was about a 27% premium to Blueprint’s previous close – a sizable but not exorbitant uplift for a premium (suggesting perhaps Blueprint was already trading with some buyout speculation baked in).

Smaller targets saw even larger percentage jumps: 2seventy bio’s stock jumped 76% pre-market when BMS’s ~$5/share, +88% premium offer was announced. In general, target shareholders were big winners: Regulus’s share price roughly doubled (108% premium) under Novartis’s bidxtalks.com; Vigil Neuroscience likely saw a major jump to approach the $8 offer (the stock had languished around $3–4, so $8 was a significant upside).

Checkpoint Therapeutics’ stock went up on Sun Pharma’s deal news, approaching the $4.10/share tender price (it was around $2.47 before, so the 66% premium got captured. These reactions underscore that buyers had to pay premiums – often in the range of 50–100% for small/mid biotechs – to secure the deals. However, it’s worth noting that in many cases these premiums, while large, still left some target investors under water relative to earlier highs.

For instance, Kronos Bio’s $0.57/share exit was sadly far below the several dollars per share it traded at a year prior – but given that without a deal it might have gone to $0, investors still “celebrated” the salvage value. Overall, target investors have been lobbying for M&A in many cases (given weak IPO and financing markets), so these deals were greeted as positive outcomes.

Acquiring Company Shareholders

Acquirers’ stock reactions were mixed-to-slightly negative in the short term, which is typical since the acquirer is spending cash or taking on risk. For example, Sanofi’s shares fell modestly (~1–2% down) on the day it announced the Blueprint acquisition, as investors digested the $9.5B expense and the long payback horizon of that investment. Such a dip is common for large deals – essentially the market saying “show me this was worth it.” However, these declines were not severe, indicating that investors largely approved the strategic rationale.

In Sanofi’s case, analysts noted the company still had sizeable capacity for further acquisitions even after Blueprint, which likely reassured investors that Sanofi wasn’t overextending financially. BMS’s stock barely moved on the 2seventy buy – $286M is a drop in the bucket for BMS (which has a $140B market cap), and investors likely viewed it as a savvy, cost-effective deal to solidify Abecma’s position.

AstraZeneca’s stock was neutral around the EsoBiotec deal – again, $1B for a pipeline platform is moderate for AZ, and it fits long-term strategy (though some analysts likely asked questions about technical hurdles in in vivo CAR-T). Merck KGaA’s stock in Germany ticked up slightly after the SpringWorks deal was seen as a bold move to rejuvenate its pipeline (and it had been telegraphed; recall Merck KGaA had signaled advanced talks in February, so it wasn’t a surprise). In short, investors seem to favor these “tuck-in” acquisitions – they are relatively easy to absorb and can be high-impact. Contrast this with mega-mergers (like a hypothetical Pfizer buying another big pharma), which often cause acquirer stocks to drop sharply on integration fears; we didn’t have those in Q2 2025.

Sector Sentiment

Importantly, each deal’s announcement often had a halo effect on the broader biotech sector, especially small-cap biotech indices. For instance, after Sanofi’s buyout of Vigil Neuroscience (targeting Alzheimer’s), shares of other CNS-focused small biotechs (like Ventyx Biosciences, which had a negotiation right with Sanofi) jumped in sympathy.

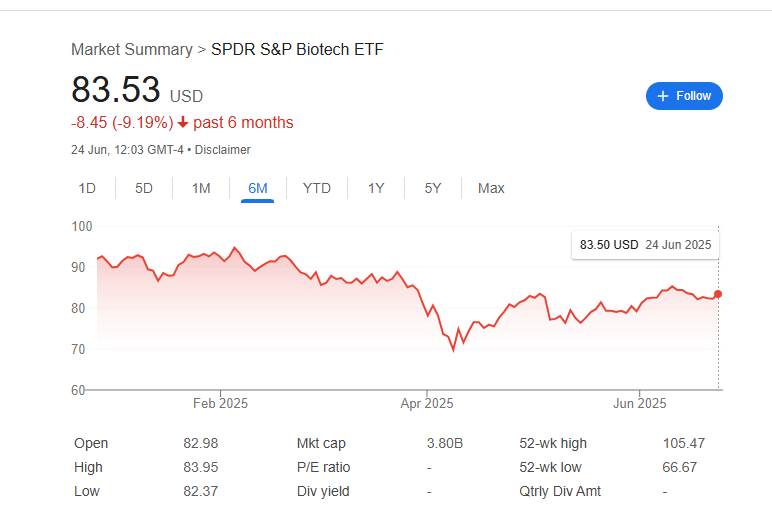

The logic: if one small neuro company got bought, others might be next. Similarly, the Regulus and Inozyme acquisitions buoyed sentiment for other rare disease and RNA therapy biotechs – a sign that big pharma is shopping in those areas. The cumulative effect of multiple deals by mid-year was a notable improvement in investor sentiment for biotech. At the start of 2025, biotech indices were near multi-year lows; by June, the XBI (small-cap biotech ETF) had recovered some, partly on hopes that M&A will put a floor under valuations.

Jefferies’ note on increased small-cap M&A potential was taken as bullish for the sector, with the firm predicting many more takeouts in the coming 6–12 months given the conditions. When large investment banks publicly highlight that 80+ biotechs trade below cash and could be targets, it injects speculative interest into the sector. Indeed, throughout Q2, biotech stocks often popped on any hint of buyout rumors (for example, after J&J’s Intra-Cellular deal, other CNS stocks rose on speculation of who might be next).

This “M&A put” provided some downside protection: investors felt that even if a biotech’s own prospects were uncertain, the chance of a buyout at a premium made them worth holding.

Analyst Reactions

Equity research analysts largely praised the strategic logic of these deals, with some debates on price. For Blueprint, most analysts agreed it was a unique asset (only approved SM drug) and fit Sanofi’s strategy, though a few questioned the 27% premium for a company that was not cheap to begin with. However, others noted that Blueprint brings an immediate revenue product (Ayvakit) growing quickly in a niche – something that can justify the price.

BMO Capital commented positively on Lilly’s SiteOne buy as diversifying away from GLP-1s, indicating that analysts like when pharma addresses concentration risk via M&A. In the small deals, analysts saw them as smart, low-risk bets – e.g., “BioMarin’s bold move ignites its rare disease evolution” one headline read, and RBC or Jefferies likely viewed BMS’s 2seventy buy as a “no-brainer” to consolidate a partner.

One analyst tidbit: Jefferies highlighted how some pharmas (e.g., Sanofi) had right-of-first-negotiation (ROFN) agreements with biotechs (like Vigil, and also Ventyx for Parkinson’s) and that those ROFNs were now turning into actual acquisitions. This suggests analysts are tracking these contractual clues and found it encouraging that pharmas are exercising their options to buy when data is favorable.

Integration and Execution Concerns

The market will of course be watching how these acquisitions are integrated and executed. A premium buyout only creates value if the acquirer can speed the product to market and maximize its potential. For instance, Sanofi will need to successfully market Ayvakit in indolent mastocytosis (a new indication) and progress Blueprint’s pipeline to justify $9.5B. If any of these acquired programs falter in trials (always a risk), the acquiring stock could suffer in the long run. But in the short term of Q2, such concerns were distant; the initial reaction was mostly about strategic fit and immediate financial impact.

In summary, investor reaction has been positive for the biotech sector and measured for big pharma. Targets got their well-deserved pops, validating the board decisions to sell. Pharma buyers mostly convinced shareholders that these deals make sense – no CEOs were ousted over a bad deal here, and no acquirer’s market cap dropped more than the deal’s cost (a good sign the market thinks they didn’t overpay drastically). The flurry of deals by mid-year also built investor confidence that M&A is back as a catalyst for the industry, which can drive further investment into biotech R&D knowing there’s an active exit market. As Jefferies noted, many small biotechs may now consider M&A as“in the best interest of shareholders given market conditions – a statement that itself reflects how shareholder mindset has shifted from holding out for solo success to gladly accepting a takeover when it comes. This psychology bodes well for more deals: willing sellers and willing buyers.

Conclusion

The March–June 2025 period marked an inflection point in pharma and biotech M&A activity, with a series of strategic acquisitions injecting fresh energy into the sector. The deals spanned a spectrum from multi-billion-dollar headline grabbers to quietly important sub-$300M tuck-ins, collectively addressing critical needs: new therapies for cancer, autoimmune diseases, rare genetic conditions, neurological disorders, and more. Strategic drivers – such as pipeline replenishment, acquiring novel technologies, and capitalizing on low biotech valuations – were evident in deal after deal.

We observed clear themes of oncology dominance, an immunology push, careful steps into CNS, and the opportunistic consolidation of undervalued assets. Geographically, the transactions highlight the global nature of biotech innovation and the global reach of pharma companies in sourcing that innovation. And importantly, investors have largely welcomed this M&A resurgence, as it provides paths to monetize R&D and underscores pharma’s commitment to growth.

For decision-makers in healthcare investing and corporate strategy, these developments carry several implications:

- Pharma companies are likely to continue aggressive business development in their areas of strength (e.g., oncology, immunology). Identifying biotechs with compelling assets in those areas – especially those undervalued due to market conditions – could present investment opportunities ahead of a potential acquisition.

- The “buyer’s market” for biotech innovation may persist until overall biotech financing improves. This suggests that corporates with cash should remain vigilant and ready to execute deals, while biotech boards might lean towards deal-making earlier rather than later when faced with cash crunches.

- Integration planning is crucial. Many of these acquisitions involve complex science (cell therapy, RNA drugs, etc.) – the acquirers will need to effectively integrate new teams and technologies. Strategy leaders should ensure that post-merger integration plans preserve the innovative culture and expertise of the acquired teams to avoid loss of value.

- Investor sentiment is fickle but currently supportive of smart M&A. Corporate strategists should communicate clear strategic rationale for each deal (as most did in Q2 2025), which helps maintain shareholder support even if spending billions. The market rewards focus: Sanofi saying Blueprint fits its rare immunology mission, or GSK articulating how efinosfermin aligns with its fibrosis strategy, etc., were effective narratives.

- Emerging areas like digital health and AI in pharma will likely be addressed more via partnerships in the near term, but as those technologies mature, do not rule out future acquisitions (for instance, a pharma might eventually acquire a real-world data company outright to internalize those capabilities). Strategy teams should monitor where owning a digital capability provides competitive advantage versus simply collaborating.

- Geopolitical factors (e.g., U.S.-China relations) will continue to influence dealmaking routes. For example, U.S. and European firms might prefer licensing deals with Chinese counterparts rather than acquisitions. Conversely, Middle Eastern or other non-traditional investors might step in to acquire assets if Western pharmas overlook them. Keeping a global perspective is essential.

Ultimately, the M&A wave of 2025 appears to be a sign of a healthy innovation ecosystem: groundbreaking science is being rewarded and advanced by those with the resources to do so. For industry stakeholders – whether they are pharma executives plotting the next acquisition, biotech entrepreneurs positioning for a buyout, or investors allocating capital – the first half of 2025 has provided valuable lessons and confidence that targeted M&A is a powerful tool to drive progress in healthcare. If these trends hold, we can expect the remainder of 2025 to bring further exciting deals, continued convergence of technology and therapeutics, and a reshaping of the pharma landscape as companies align their portfolios with the therapies of the future. The deals between March and June 2025 have laid the groundwork for that future, one acquisition at a time.

Member discussion