In Praise of Discomfort: Why Less Government Funding Might Be Good for Science

There are few things more sacred in biotech than the sanctity of government grants. At the heart of this cathedral sits the National Institutes of Health (NIH), a $49 billion-a-year colossus that dispenses lifeblood to labs, startups, and research institutions alike. In countless ways, NIH funding is the foundation on which American biomedicine is built.

But herein lies the problem: when a system becomes reliant on one source of support—especially a source as politically insulated and reputation-based as the NIH—it risks becoming fragile.

This is not an argument against science. Nor is it a call for fiscal hawkishness in lab coats. It is, rather, a Talebian critique: a system that is shielded from stressors loses its capacity to adapt. It becomes increasingly fragile, and over time, increasingly mediocre.

In other words: we might be better off with less NIH funding—not because we hate science, but because we love progress.

NIH, Fragility, and the Fallacy of More

Over the past 30 years, NIH budgets have expanded dramatically. Yet, if you track outputs—therapeutic breakthroughs, new molecular entities, drugs approved per dollar spent—efficiency has flatlined or declined. This paradox is captured in “Eroom’s Law” (Moore’s Law spelled backwards), which observes that drug development becomes more expensive and less efficient with time, despite technological gains.

Part of the explanation lies in the structure of the funding ecosystem. NIH grants reward conservatism. Proposals must appeal to consensus panels. Radical ideas are often filtered out in peer review. Scientists are incentivized to seek fundability, not feasibility.

And thus, over time, labs orient toward what will be funded, not what should be explored.

What this creates is the illusion of stability. Funding flows. PDFs are submitted. CVs expand. But underneath it all, progress stalls. The fragility Taleb warned of in Antifragile—a condition where apparent robustness hides systemic brittleness—is alive and well in biomedical science.

How Taleb Would See It

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the former options trader turned philosophical bomb-thrower, provides a piercing lens through which to evaluate modern science funding. In Skin in the Game, Taleb notes that any system where people bear no downside from their decisions is structurally corrupt. NIH-funded science suffers from this pathology. The reviewer who torpedoes a bold idea, the academic who wins another grant to rehash their last publication, the bureaucrat who avoids risk—all are insulated from the consequences of not taking a chance.

Taleb would ask: where is the asymmetry? Where is the optionality? Where is the downside?

In his world, systems thrive when they are allowed to absorb volatility, when small failures are frequent, and when rewards are convex—massively skewed toward rare, high-payoff events. The current system is the opposite: linear, rigid, and highly averse to reputational risk.

True innovation—Black Swan-level innovation—demands discomfort.

Antifragility and the Case for Creative Stress

One of Taleb’s most potent concepts is antifragility. Unlike resilience, which merely resists shocks, antifragility benefits from them. Muscles are antifragile. Markets are antifragile. Ecosystems—when allowed to evolve without artificial cushioning—are antifragile.

The current life sciences funding model is not.

It has become, in a word, comfortable.

But comfort, like subsidies, is addictive. When risk is anesthetized, ambition withers. Over time, we don’t just fund fewer breakthroughs—we train an entire generation to avoid the discomfort necessary to achieve them.

And that, precisely, is why we must embrace new funding models—ones that welcome volatility, accept the occasional spectacular failure, and seek asymmetric upside.

Venture Philanthropy: Embracing Risk with Purpose

This brings us to venture philanthropy—a hybrid approach that blends the mission of philanthropy with the discipline of venture capital. The model is simple: deploy catalytic capital into high-risk, high-impact biomedical projects, and recycle any returns back into the mission.

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation famously pioneered this approach, backing Vertex Pharmaceuticals in a then-controversial move that led to both a clinical breakthrough and a multibillion-dollar return. They didn’t just fund science. They shaped the outcome.

Unlike NIH grants, venture philanthropy is not bound by peer consensus. It doesn’t need five references from Cell and Nature. It needs vision, conviction, and an understanding of optionality—that most bets won’t pay off, but one success could transform a disease landscape.

What We’re Doing at Capital for Cures

This is precisely what we are building with Capital for Cures—a platform that aligns bold science with mission-driven, risk-tolerant capital.

The premise is simple, but the implications are radical: the current biomedical capital stack is broken. NIH funds early ideas but not translation. VCs want validated de-risked assets. Family offices dabble. Pension funds flee. What’s missing is a translational middle—capital that dares to enter when the outcome is still uncertain, but the data is tantalizing.

At Capital for Cures, we:

- Identify promising science that can’t get traditional funding

- Design catalytic financing mechanisms with aligned upside

- Convene philanthropists, investors, and industry to co-fund risk

- Push the Overton window of what kinds of biotech finance models are considered acceptable

We believe this is not just an innovation problem. It is a capital design problem. And it needs fixing—not with more grants, but with better incentives.

Europe’s Quiet Capital Crisis

In Europe, the dynamics are even more dire. Despite world-class research institutions and a deep pool of scientific talent, the continent is chronically underfunded when it comes to early-stage biotech.

Part of the problem is structural. European pension funds manage over €3.3 trillion in assets. And yet, less than 0.1% is allocated to venture capital. Of that, a microscopic fraction reaches biotech.

This is not just suboptimal. It is a colossal misallocation of capital.

European pension funds—unlike hedge funds—are ideally suited to fund biomedical innovation. They have long-dated liabilities. They operate on intergenerational time horizons. They care about real-world impact. And they could easily tolerate the risk profile of biotech—if only the right vehicles existed.

At Capital for Cures, we are actively building those vehicles.

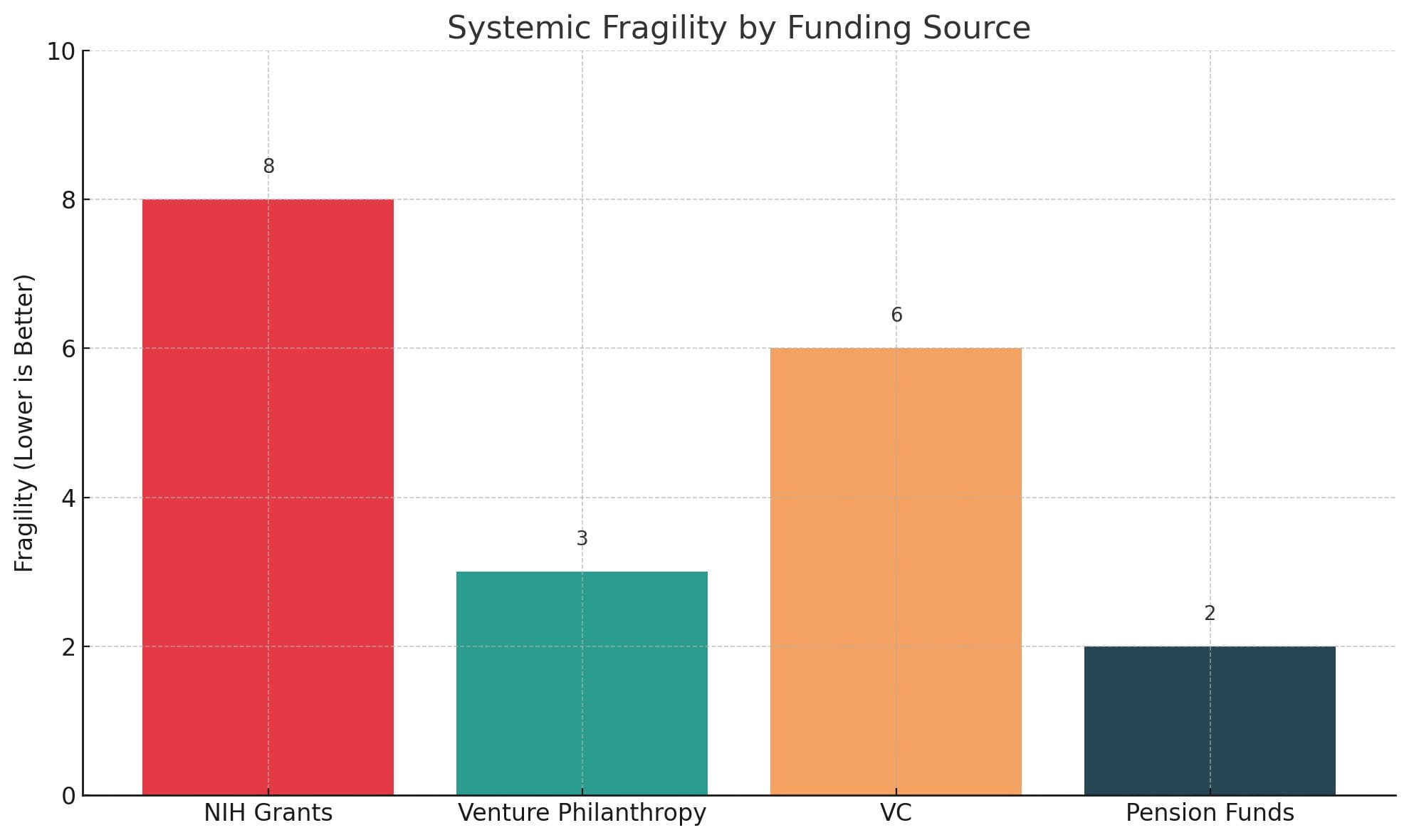

Visualizing Fragility

To illustrate the point, consider this simple chart. It captures how different funding sources impact systemic fragility in biotech:

- NIH grants offer stability but at the cost of boldness

- VC introduces volatility but is often too late

- Pension funds sit idle—despite their immense potential

- Venture philanthropy uniquely offers low fragility and catalytic potential

The goal is to fund in the green zone—where ideas are still fragile, but the capital is antifragile.

Shifting the Overton Window

Arguing that NIH funding should decrease is not just contrarian. It is currently unthinkable within the Overton window—the spectrum of socially acceptable discourse.

But windows move.

And just as Taleb’s early critiques of over-optimization, debt-fueled growth, and systemic fragility were once fringe—and are now canonical—so too must we expand the boundaries of debate in biomedical finance.

To shift capital flows, we must first shift the conversation.

This blog, this platform, and Capital for Cures as an initiative exist to make those shifts thinkable. Fundable. Scalable.

Final Thoughts: A System Worth Stressing

Let me be clear: science is a public good. The NIH has done immense good. But the next frontier of biomedical breakthroughs will not come from pouring more money into the same pipes.

It will come from reengineering the capital stack. From welcoming volatility. From giving ideas room to fail early and succeed wildly.

This is what Taleb means by “via negativa”: don’t add more. Subtract what no longer works.

Let go of the comfort. Reclaim the edge.

Postscript: For readers in Brussels, Berlin, or Bethesda tempted to send angry emails—rest assured, this is not an argument to dismantle the NIH or its European equivalents. It is an argument to rethink our dependencies. Funding is a tool, not a religion. And sometimes, the best thing a system can do… is step aside.

Member discussion