New Funds on the Block: The First-Half Year Check-In on Biotech VC & PE

The first half of 2025 has seen a wave of new venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) funds dedicated to pharmaceuticals and biotech, even as the broader funding climate remains cautious. Investors are selectively raising and deploying billions into life sciences – from mega-funds amassing war chests for drug development, to specialized vehicles targeting niche diseases or distressed assets.

This report provides an in-depth look at the new funds launched or announced up to July 2025, their sizes, focus areas, locations, and the context behind their formation. The trend reveals a paradox: fewer funds are closing, but those that do are larger than ever (biopharmadive.com), reflecting both confidence in biotech’s long-term prospects and the realities of a tougher market. Below, we profile these funds in detail and examine what their emergence signals for the global pharma and biotech industry.

A Changing Funding Landscape in Biotech

The biotech venture funding frenzy of 2020-2021 – fueled by low interest rates and a boom in IPOs – has given way to a more sober environment in 2024-2025. Rising interest rates and weak stock market exits have made investors more discerning. By 2024 the number of new biotech VC funds had dropped sharply from the 2021 peak (137 funds) to just 38, although the total capital raised ($16 billion) only roughly halved. In other words, more capital is flowing into fewer funds, with established players able to raise supersized funds while many emerging managers struggle. Venture firms are prioritizing larger, later-stage deals – “companies that demonstrate validated clinical data and clear commercialization pathways,” as one analyst noted. Early-stage and seed investing, by contrast, faces “significant challenges” due to the scarcity of new fund closures among newer VCs (biopharmadive.com).

Yet, even amid a “bear market” for biotech, strong convictions remain. There has “never been a better time to invest” in life sciences, insists James Flynn of Deerfield Management. The first half of 2025 has proven that point, with several major life science-focused funds closing – often above target – and new innovative funds launching to fill gaps in the ecosystem. These range from multi-billion-dollar generalist funds to boutique vehicles for specific diseases or strategies. Geographically, North America and Europe dominate the fundraising, but Asia – notably Japan – and other regions are also crafting initiatives to bolster their biotech sectors.

Some key trends from H1 2025 include

Mega-Funds March On

Established VC/PE firms raised record-sized funds for life sciences, signaling long-term confidence. Large managers like Blackstone, ARCH, and Sofinnova pulled in $1–5 billion+ per fund (detailed below), often exceeding initial targets.

Strategic & Corporate Capital

Big Pharma and tech investors are teaming up with VCs, as seen in the Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) and Eli Lilly $500 million fund focusing on new drug technologies (reuters.com). Corporate and strategic LPs are anchoring many funds to gain early access to innovation.

Disease-Focused Funds

Specialized funds zeroing in on particular therapy areas are on the rise. In 2025, new vehicles launched to target dementia (neurodegeneration), autoimmune diseases, and other niches often underfunded historically (svhealthinvestors.com).

Continuation & Secondary Funds

With IPOs scarce, venture firms are increasingly using continuation funds (GP-led secondary vehicles) to extend support for promising portfolio companies and provide liquidity to investors. Such secondary transactions hit record volumes in 2024 (over $70 billion in GP-led deals, nearly half the $152 billion secondary market), a “surge expected to continue” through 2025 (robinai.com).

Globalization and Partnerships

New cross-border funds emerged, such as a US-Japan joint fund aiming to turn Japan’s “untapped” biotech research into global companies. Meanwhile, government agencies and pension funds (from Canada to the EU) stepped up as LPs to stimulate local biotech innovation (businesswire.com).

Focus on Value-Add

Many new funds emphasize not just capital but also expertise – whether via AI and data capabilities (in tech-bio funds) or ties to philanthropic foundations and academia (in disease-focused funds) – to better nurture young biotech ventures.

In the following sections, we profile notable new VC and PE funds of 2025 (through July) – outlining who raised them, their size, therapeutic focus, and location – and discuss their strategic significance. We also include insight on funds currently fundraising and recently announced, since these indicate where capital may flow in the coming months. To lighten the analysis, we intersperse graphical highlights and summaries.

The Billion-Dollar Club: Mega-Funds Continue to Grow

Even in a more selective market, large-cap life sciences investors keep breaking records. Leading the pack is Linden Capital Partners, a Chicago-based healthcare private equity firm, which closed its sixth fund in April 2025 at $5.4 billion (including a $200 million GP commitment). This oversubscribed fund blew past its $4.5 billion target and is Linden’s largest to date, coming just 3.5 years after its previous $3.0 billion fund. Linden – one of the biggest dedicated healthcare buyout firms – will use Fund VI to continue its strategy of mid-market acquisitions in healthcare services, medical products, and distributionlinden.com. The speedy nine-month fundraising for such a sum, amid a tough market, underscores LPs’ trust in Linden’s 20-year track record and the strong returns from healthcare deals (linden.com).

Not far behind, Blackstone Life Sciences – the life science investment arm of the private equity giant – revealed in early 2025 that it is raising a new life sciences-focused fund targeting at least $5 billion. By January 2025, Blackstone had secured an initial $1.6 billion toward this vehicle. If it meets the $5B goal, the fund would rival Blackstone’s prior $4.6 billion biopharma fund from 2020. Blackstone’s strategy spans investing in emerging biotech companies, late-stage product financings, and even large collaborations with pharma. According to the firm, its life sciences portfolio has helped bring over 160 medicines to market, with an impressive 85% Phase III success rate – a testament to focusing on derisked, clinically validated opportunities.

The new fund, management noted, follows a “standout” 2024 performance for Blackstone’s life sciences group, which saw a 33% appreciation in its holdings and multiple positive drug development milestones (biospace.com). In essence, Blackstone is doubling down, and LPs have responded enthusiastically.

Other established venture firms closed similarly colossal funds in late 2024 and early 2025. In September 2024, ARCH Venture Partners – one of biotech’s most prominent early-stage VCs – closed its eighth life sciences fund at $3 billion. ARCH VIII focuses on cutting-edge areas like AI-driven drug discovery and data-centric biotech platforms, reflecting a trend of tech convergence (more on that later).

The same month, Bain Capital Life Sciences also raised $3 billion for its fourth fund, earmarked broadly for biopharma and medtech companies working on “transformative” products (biospace.com). These multi-billion funds by ARCH and Bain indicate that top-tier investors still managed to raise even larger pools than prior years, despite the industry downturn – a sign that pensions, endowments and sovereign funds remain bullish on long-term healthcare innovation. Indeed, Bain’s fund IV and ARCH’s fund VIII were among the largest biotech VC funds ever raised globally.

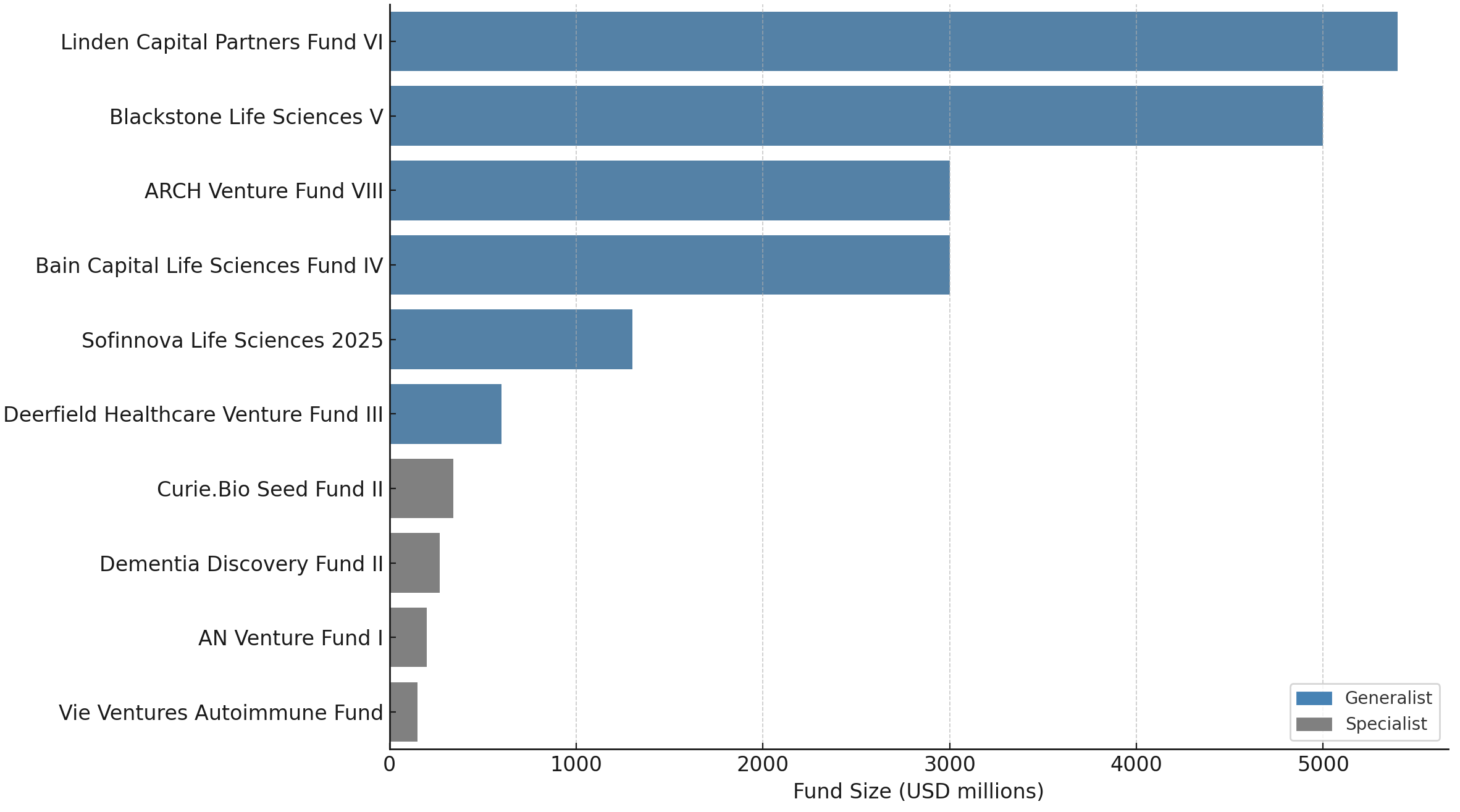

Selected new VC/PE funds in life sciences (launched or closed in late 2024 and H1 2025), with their sizes in USD millions. Established generalist funds (blue) dwarf specialist and seed funds (gray), highlighting a concentration of capital among a few large players (dakota.com).

Even European VCs are notching big wins. In March 2025, Sofinnova Partners, based in Paris, announced it had raised a hefty €1.2 billion (~$1.3 billion) across new funds to invest in life sciences. This fresh capital – one of the first major closings by a life sciences venture firm in 2025 – will allow Sofinnova to back 50–60 new companies in biotech, medtech and health-tech over the coming years (biopharmadive.com).

The raise brings Sofinnova’s assets under management to over €4 billion, solidifying its place among Europe’s top biotech investors. Sofinnova did not break down the €1.2B into individual fund vehicles (they manage multiple strategies, from early-stage startup creation to late growth rounds), saying details would come upon final closings. Nonetheless, the sheer scale of this raise – which follows several $2B+ funds by peers like Arch, Forbion and Flagship in the prior year – shows that Europe’s life science VC scene can attract mega-fund commitments even in a “sluggish” environment (biopharmadive.com).

It likely helps that Sofinnova has had recent high-profile wins (e.g. portfolio companies CinCor and Amolyt were acquired by AstraZeneca in 2023–24), giving LPs confidence.

Alongside these, Deerfield Management – a hybrid venture and credit investor in healthcare – closed a notable new fund in May 2025. Deerfield announced the close of its third healthcare venture fund, raising over $600 million for deployment into biotech startups and medical technology. This fund (operating out of Deerfield’s “Cure” innovation campus in New York) will back companies developing therapeutics, medical devices, and healthcare services.

Deerfield’s managing partner James Flynn struck an optimistic tone, saying “advancing knowledge, data and software capabilities are transforming what is possible” in health, making now a great time to invest. Deerfield’s previous venture fund was larger ($840 million in 2020), so this year’s fund III is actually a bit smaller – perhaps reflecting a calibrated approach. Still, in a challenging market Deerfield managed to secure commitments from its network of LPs (the firm manages over $15 billion total). Notably, Deerfield’s activity bridges both venture creation (it partners with 30 academic institutions to launch startups) and more traditional growth financing. By early 2025, Deerfield joined Sofinnova, a16z, and Curie.Bio in the select club of firms closing new biotech funds, as BioPharma Dive pointed out (biopharmadive.com).

What unites these giant funds? They are largely generalist life science funds investing across many disease areas and company stages, albeit with a bias toward more mature programs in an era of risk-aversion. Their limited partners (investors) include big institutions (pension funds, endowments), sovereign wealth, and corporates.

These funds also illustrate the trans-Atlantic nature of biotech finance: U.S. funds like Blackstone and Deerfield pour money into both domestic and overseas startups, while European funds like Sofinnova increasingly syndicate with U.S. investors on big rounds. For example, Blackstone’s prior fund helped finance companies globally, and Sofinnova’s new capital will likely back U.S. firms as well as European ones. The mega-fund trend suggests that a handful of experienced firms are becoming gatekeepers of biotech venture financing, able to write $50–100M checks and lead “mega-rounds” that have become common in the absence of IPO exits (biopharmadive.com).

However, as Tristan Manalac of BioSpace notes, these massive raises don’t tell the whole story of biotech. They tend to favor later-stage, de-risked bets, leaving a gap in funding for scrappy early-stage biotechs or unproven science. Many smaller VCs have struggled to raise fresh funds, which could mean fewer options for seed-stage startups. Industry observers like Sara Choi of Wing VC worry that the Series B stage is seeing a “drop off” in funding – a concerning trend if true (biospace.com). This is where some newer funds are stepping in with creative approaches, as we explore next.

Strategic Partnerships: When Pharma Meets VC

In 2025, big pharmaceutical companies have shown they’re not content to simply be on the sidelines as LPs – some are directly co-creating venture funds to get closer to innovation. A headline-grabbing example came in January 2025, when Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), the Silicon Valley venture firm, announced it was launching a $500 million biotech fund in partnership with Eli Lilly (reuters.com).

Unusually, this Biotech Ecosystem Fund is fully funded by Lilly as the sole limited partner – essentially a corporate venture fund managed by a16z’s bio team. Lilly’s capital will be invested in cutting-edge therapeutic platforms, novel engineering technologies, and AI-driven drug discovery startups. Beyond money, Lilly will offer the portfolio companies access to its vast R&D expertise – “pre-clinical and clinical development talent and resources,” as Lilly promised (reuters.com).

The logic is clear: Lilly gains an early window on emerging science (and a stake in the upside), while startups get not just VC funding but also pharma know-how. “Combining our strengths will empower founders with venture backing and the resources to strategically select promising application areas,” said a16z general partner Vineeta Agarwala (reuters.com).

For a16z, which already has a large Bio + Health fund, this collaboration is a way to expand its firepower in biotech investing with corporate money, at a time when pure-play VC dollars are scarcer. It’s also a vote of confidence by Lilly in a16z’s team to scout the next big breakthroughs. We can expect this fund to emphasize areas aligning with Lilly’s interests – possibly new therapeutic modalities, AI in drug design, and platform biotechs – essentially augmenting Lilly’s own research pipeline with external innovation.

Pharma-linked venture initiatives are not new (many Big Pharmas have in-house venture arms), but the a16z-Lilly model is a novel hybrid. It reflects how pharma companies are seeking creative ways to deploy capital amid a biotech downturn – leveraging VCs’ deal flow while influencing investment toward areas of strategic interest. Another instance is Leaps by Bayer, Bayer’s impact investment unit, which continues to co-invest with VCs in areas like cell therapy and sustainability, albeit not via a dedicated new fund in 2025.

And in Europe, the Dementia Discovery Fund (DDF) – while not new – is backed by multiple pharmas (Biogen, Lilly, Pfizer, etc.) as LPs along with government and nonprofits (svhealthinvestors.com). The DDF’s new second fund closing in 2025 (covered below) exemplifies how consortia of pharmas and foundations can pool resources into venture-style vehicles targeting a shared mission (in this case, Alzheimer’s and dementia drugs).

Also bridging corporate and venture worlds is AN Venture Partners, a unique U.S.-Japan VC firm formed in partnership with ARCH Venture Partners. AN Venture Partners (ANV) announced in July 2025 the final close of its debut fund at $200 million (fiercebiotech.com). The firm is based in San Francisco and Tokyo and was established in 2022 with support from ARCH (a long-time investor in both U.S. and Asian biotechs).

ANV aims to invest across all stages – it’s modality-agnostic and disease-agnostic – but has a special focus on tapping “science sourced from Japan” and helping build it into global companies. In effect, ANV sees Japan’s academic and biotech research as an underexploited well of innovation (an “untapped source” in their words) that, with venture building expertise, can generate startups competitive on the world stage (fiercebiotech.com).

So far AN Venture Partners has backed seven companies, including some in stealth and others spanning the US-Japan corridor – for example, it funded Typewriter Therapeutics, a biotech supported by a Japanese government program to boost pharma startups (fiercebiotech.com). Importantly, ANV’s LP base itself reflects the strategic intent: Over 20 LPs joined the fund, led by the Japan Investment Corporation (JIC, a sovereign fund) and major Japanese pharma companies like Shionogi and Otsuka, plus big Japanese banks (MUFG, SMBC).

In short, Japanese public and private sectors are literally investing in this VC fund to invigorate their biotech pipeline. This model – a government-backed VC vehicle operated with global expertise (ARCH’s involvement) – could be a blueprint for other countries seeking to bridge domestic science with international venture networks.

From the Middle East, we are seeing interest too, albeit more in direct investments than new funds. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), for instance, has signaled an initiative to position the Kingdom as a biotech hub by 2030, coordinating policy and capital (as discussed at BIO 2025 in a Saudi panel).

While PIF hasn’t launched a dedicated biotech fund for outside managers, it’s allocating substantial resources internally and via partnerships to life sciences (e.g. investing in global funds and companies). Similarly, Mubadala in the UAE continues to be an active investor in healthcare and often anchors funds (Mubadala was an LP in several U.S. funds like in SV’s DDF, and co-investor in venture rounds). These moves underscore a globalization of biotech funding – capital can come from anywhere, and regions rich in cash (but historically light in biotech) want a piece of the biomedical innovation pie, especially after the pandemic highlighted its importance (globenewswire.com).

New Kids on the Block: Emerging and Niche Venture Funds

Amid the giants, a new generation of venture capitalists has arrived on the biotech scene, bringing fresh models and targeting gaps left by traditional VCs. These up-and-coming funds in 2024-2025 often blur the lines between accelerator, incubator, and VC, and many are highly focused – either on a stage (e.g. seed) or a technological edge (e.g. AI, machine learning). Several standouts:

Curie.Bio – $340 million Seed Fund II (2025)

Few new biotech investors have generated as much buzz as Curie.Bio. Launched in 2022 by veteran biotech founder Alexis Borisy and tech entrepreneur Zach Weinberg, Curie.Bio is part accelerator, part venture fund aimed at “upending the biotech financing model” (statnews.com). Its premise is to provide not only capital but also hands-on drug development support (a “co-piloting” model) to scientists launching new therapeutic startups – essentially an Y Combinator meets contract research organization for biotech.

In January 2025, Curie.Bio closed its second seed fund at $342 million, securing commitments from 46 investors according to SEC filings. This was above an initial target (Fund I targeted $275M), reflecting strong interest in Curie’s approach. Notably, Curie had also raised a separate $380 million Series A fund in 2024 to continue backing its portfolio companies as they advance to clinical stages (dakota.com).

In total, by 2025 Curie.Bio amassed over $1.2 billion across its funds to datestatnews.com, a remarkable feat for a two-year-old firm.Curie.Bio’s investment focus is broad in therapeutics (platforms and “asset-centric” companies with potential blockbuster drugs), but what sets it apart is efficiency and founder-friendliness. The team boasts it has a <1% acceptance rate, picking the best from thousands of biotech startup applicants. With Fund II, Curie plans to double the number of startups it launches per year (to ~15–20 in 2025).

It typically invests $5–10M as seed into each and guides the company through early experiments to a value inflection point (curie.bio). By bundling services and capital, Curie can get a drug concept off the ground with less dilution for founders. The success of its raise suggests LPs buy into this leaner, faster model of biotech venture – one perhaps more resilient in a tight market. Indeed, Curie’s growth is a positive counterpoint to Helal’s observation about scarce new funds for emerging managers (biopharmadive.com); here is an emerging manager thriving by being different.

Dimension – $500 million Fund II (2024)

Another rising star is Dimension Capital, a firm explicitly operating at the intersection of computation and biology. Co-founded in 2021 by Adam Goulburn (ex-Lux Capital), Zavain Dar, and Nan Li, Dimension quickly raised a $350M first fund in early 2023 and then, in December 2024, closed Fund II with $500 million. This overshot its $400M target and could have been larger if not for a hard cap – a sign of strong demand even in late 2024’s slump. Dimension’s thesis is that “biotech’s convergence with tech” – applying AI, machine learning, automation, etc. – will produce outsized opportunities.

They position themselves as contrarian for still backing earlier-stage, tech-heavy biotechs at a time many VCs flock to safer bets. The team is equally versed in coding and biology, aiming to invest in both therapeutics companies and in the tools/tech that enable drug discovery and manufacturing. For example, their portfolio includes AI-driven drug designers (like Chai and Kimia Therapeutics) as well as lab automation and bioinformatics startups (biopharmadive.com).

With $500M, Dimension will make only ~20 investments (concentrated, big bets with up to $40M in each). They explicitly avoid the “spray and pray” approach – “Many of our brethren end up on 30–40 boards; it’s impossible to pay attention to all”, says Dar, noting Dimension will hold about 20 board seats so they can give deep support to each founder. This focus on fewer, bigger bets with high engagement is a model reminiscent of some successful tech VCs, and aligns with the trend of larger rounds for chosen startups (fiercebiotech.com).

However, it’s still a bold strategy given many of Dimension’s companies are pre-revenue and unproven; by late 2024 they had not seen any exits yet. The partners argue they can afford patience due to 10-year fund horizons and that their “risk-on” investments in potentially “highly transformative ideas” will pay off in time (biopharmadive.com).

If AI+biotech truly revolutionizes R&D, funds like Dimension II will be well-placed – and indeed LPs seemed to feel they couldn’t miss out on the AI biotech wave, helping Dimension raise this fund quickly. (The fervor for AI in drug discovery also led to Arch’s $3B focus and multiple large rounds for AI-driven startups in 2023-25.)

SV Health Investors – Dementia Discovery Fund 2 ($269 million, 2025)

Not all new funds are broad; some are laser-focused on a single therapeutic area. Dementia Discovery Fund (DDF) is a case in point – a specialized venture fund exclusively investing in novel dementia therapies. Managed by SV Health (UK/US firm), DDF launched in 2015 with backing from government, pharma and philanthropy, and has now become the world’s largest dementia-focused VC vehicle. In May 2025, DDF announced the final close of its second fund (DDF-2) at $269 million. This brings DDF’s total capital to over $550M across the two funds (svhealthinvestors.com).

DDF-2 has already started putting money to work – it’s invested in four companies so far that are developing life-changing treatments for Alzheimer’s and other dementias. The fund expects to build a portfolio of 10–15 companies in total, primarily in the US, UK, and Europe.What makes DDF notable (besides its mission in an area of huge unmet need) is its investor base and collaborative model. Its cornerstone LPs include the likes of the Gates Foundation, Alzheimer’s Association, AARP, and a who’s-who of pharma companies (Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Pfizer, J&J, etc.). They share a dual mandate: deliver returns and tangible impact for patients.

DDF leverages an extensive network of venture partners and neuroscience experts (the team collectively has 200+ years of neuro R&D experience) to scout and nurture projects The urgency is clear – as Kate Bingham of SV said, “unsustainable human and economic cost of dementia... we urgently need to harness innovation to tackle it” (svhealthinvestors.com). DDF’s existence and continued growth (closing a second fund above target) is encouraging, proving that even in tough times, capital will flow to mission-driven funds with credible teams. It’s a model that could extend to other diseases: indeed, SV and others have applied similar approaches in areas like rare diseases and cancer in the past.

Vie Ventures – Autoimmune Diseases (launched 2025)

Just in July 2025, a new firm called Vie Ventures made its debut, aiming to “bridge venture capital and disease philanthropy” in the autoimmune space. Co-founded by Steven St. Peter, M.D. and Luke Evnin, Ph.D., both veterans of biotech investing (MPM Capital alums), Vie Ventures will focus on Series B and C rounds for startups developing novel therapies for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (businesswire.com).

In doing so, it is partnering with leading disease foundations from day one – including the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation, Lupus Research Alliance, National MS Society, Scleroderma Research Foundation, and others, who are “strategic collaborators” to the fund. These nonprofits have funded billions in basic research; Vie wants to channel that knowledge into venture-stage opportunities. The idea is that philanthropic groups plus experienced VCs together can pick better bets and help startups succeed, ultimately getting cures to patients faster.

As evidence of commitment, Vie’s founders are even pledging a share of their own future profits to form a charitable foundation supporting autoimmune R&D.While Vie’s fund size hasn’t been publicly disclosed yet, the involvement of multiple foundations and presumably some pharma or family office LPs suggests it could be significant (possibly in the mid-nine figures, given St. Peter grew the T1D Fund to >$200M AUM previously).

Vie Ventures exemplifies a trend of “venture philanthropy” – applying VC investment with a patient-centric lens. By having folks like Dr. Lou DeGennaro (former CEO of Leukemia & Lymphoma Society) as senior advisors, and co-founders personally connected to these diseases, Vie hopes to make more informed and impactful investments. They note that despite booming immunology science (e.g. many new drugs for autoimmune conditions), huge unmet needs remain, and perhaps a more cross-disease approach (finding therapies that address fundamental immune pathways common to multiple conditions) could yield breakthroughs (businesswire.com). If successful, Vie may not only deliver returns but also validate a model where doing good and doing well align – something that could attract even more philanthropic capital into biotech ventures.

Alis Biosciences – “Trapped Capital” Strategy (launched 2025)

One of the more unusual entrants this year is Alis Biosciences, a British investment fund that launched in April 2025 with a very specific mission: to unlock the value in struggling small-cap public biotechs and return it to shareholders. Alis is targeting what it estimates as “over $30 billion in invested capital stuck in nearly 300 public biotechs” that have hit setbacks and trade far below cash value. These often are the so-called biotech “zombies” – companies with market caps smaller than the cash on their balance sheet, usually because their trials failed or they pivoted and diluted shareholders (biopharmadive.com).

Traditional outcomes for these firms (like reverse mergers or just burning cash on new risky projects) often destroy remaining shareholder value. Alis proposes an alternative: semi-structured liquidations that free the cash while still giving any viable assets a chance. Specifically, Alis would take the company private, put any drug assets into a new vehicle, return the bulk of cash to shareholders, and either help former shareholders carry on development of the asset (with Alis retaining a stake) or liquidate the assets faster than in bankruptcy. In some scenarios, Alis might itself go public as a pooled vehicle and offer investors a combo of cash and contingent value rights in any drug’s future success.

In essence, Alis is a hybrid of an activist hedge fund and a biotech PE shop.

It’s reminiscent of moves by firms like Tang Capital and others, who have indeed been buying up distressed biotechs to liquidate them and cash out investors (biopharmadive.com). What’s new is that Alis wants to do this at scale and in a more structured, perhaps more collaborative way with managements. Alis’s team includes industry veterans like Annalisa Jenkins (former head of R&D at Merck Serono) as chair. They plan to “go public in the near term”, suggesting that Alis might list itself on an exchange, effectively becoming a permanent capital vehicle for this strategy.

If so, it could offer general investors an avenue to play biotech special situations, which until now has been the domain of a few specialized investors.The launch of Alis is timely. By 2023–25, after the biotech downturn, dozens of micro-cap biotechs were trading at negative enterprise values. Calls grew louder that this “trapped capital” should be released – even STAT News and analysts openly suggested many of these companies should liquidate rather than pursue long-shot new programs. Alis is stepping into that breach.

While not a traditional VC or PE fund (it’s more like a special opportunities fund), it’s certainly part of the pharma funding ecosystem evolution. If Alis succeeds in freeing billions for reinvestment into new science, it could ironically benefit the venture market, recycling capital from failed experiments into new startups (Jenkins of Alis explicitly said recycling capital is needed to finance exciting new science). We will watch whether 2025 sees the first deals by Alis and how the market reacts.

Global Outlook: Regional Highlights and Fundraising-in-Progress

Zooming out, the new funds of 2025 reflect a global, albeit uneven, landscape

North America (U.S. & Canada)

The U.S. remains the epicenter of biotech VC/PE, with the largest funds (Linden, Blackstone, Deerfield, a16z, Arch, Bain, etc.) all rooted in American firms. American investors also dominate the new cross-border initiatives (like ARCH’s tie-up with AN Ventures in Japan, and a16z’s with Lilly). In Canada, we see continued support for life sciences: Genesys Capital, a Toronto-based VC, closed its fourth fund in June 2025 to invest in early-stage Canadian biotech and medtech companies (venturecapitaljournal.com). While terms were undisclosed in press, Genesys noted it was their “largest fund to date”, and it secured major Canadian institutional LPs including government programs (businesswire.com).

Canadian pensions also put money into funds like Forbion’s (via the VCCI program). This suggests Canada’s ecosystem is scaling up modestly, leveraging public-private support to keep promising science (like recent homegrown success stories in obesity and radiopharma) within the country. In the U.S., many established firms that raised funds in 2019–21 are expected to be back in the market soon (e.g. Third Rock, RA Capital, Frazier, Venrock), but fundraising cycles have lengthened. Pitchbook data indicated that time to final close for VC funds exceeded two years on average by 2025, so some U.S. VCs still on the road likely include mid-size and smaller funds. Anecdotally, healthcare-focused PE continues strong: aside from Linden, firms like Linden’s peer GTCR raised big healthcare funds in 2023, and specialist PE firm Linden closed an oversubscribed $400M structured capital fund in April 2025 for non-control investments (linden.com).

Meanwhile, generalist PE are a bit quieter on pharma unless they target healthcare services (the likes of KKR, Carlyle, etc., had done large healthcare funds pre-2024; in 2025 they’re more in a deployment phase).

Europe

Europe’s venture scene, while smaller, has shown resilience. Alongside Sofinnova’s blockbuster raise, Forbion, a Dutch VC, has been expanding its fund lineup. It launched a new Forbion BioEconomy Fund I in late 2023, which by January 2025 had exceeded its €150M goal, raising €164.5 million to invest in the European biotech “bioeconomy” (forbion.com). That fund, distinct from Forbion’s main venture funds, seems to focus on opportunities at the interface of biotech innovation and public markets or strategic assets – potentially crossover investments, public equities or structured deals aimed at Europe’s biotech sector health (hence “BioEconomy”).

The involvement of European pension money (e.g. Dutch pension funds put €210M across biotech funds including Forbion and Sofinnova)ipe.com underscores how European LPs are stepping up to fund life sciences domestically, amid concerns of European startups fleeing to NASDAQ listings or U.S. acquirers. The UK, despite market woes, saw SV Health Investors successfully close DDF-2 as noted, and also the launch of a new UK-based fund by Abingworth (now part of Carlyle) focused on late clinical assets – though that was in 2022, Abingworth’s model of “Clinical Co-Development Funds” remains active and may expand. Germany, France, and Belgium also have vibrant VC scenes: for instance, Jeito Capital in France (which backed several big rounds in 2025) is likely on track to raise a second fund soon, given its first €534M fund in 2020.

In Italy, Claris Ventures announced a first close of its Biotech Fund II at €100M in early 2025 (cdpventurecapital.it), pointing to momentum even in smaller markets. Overall, Europe’s new funds are midsized (tens to low hundreds of millions) rather than multi-billion, but combined with U.S. co-investment they ensure promising European science isn’t starved.

Asia

Asia’s picture is mixed. China, which in the late 2010s poured money into biotech funds and U.S. startups, has retrenched due to geopolitical and market pressures. Chinese venture firms like Qiming, Hillhouse, and 6 Dimensions remain active, but fundraising now often happens via RMB-denominated funds aimed at the local market (supported by government guidance funds). No major new USD fund launches by Chinese VCs were noted in H1 2025, but interestingly Chinese capital is still present globally – e.g. investors like Boyu and Lilly Asia Ventures joined rounds such as the $180M Series A of Timberlyne (a cross-border startup), and Lilly Asia Ventures (LAV) was a co-lead on the UK’s Verdiva Bio $410M launch in Jan 2025 (fiercebiotech.com). This indicates that Chinese and Asia-Pacific funds continue to deploy, but perhaps less ostentatiously than in the peak when nearly half of U.S. biotech VC dollars had Asian origin (reuters.com).

Internal Chinese biotech fundraising has also been dampened by a weaker Hong Kong IPO market. Nonetheless, China’s government remains committed to biotech (as part of its Made in China 2025 goals), so we may see state-backed funds or stimulus for the sector. Outside China, Japan is clearly making a concerted push via funds like AN Venture Partners and reforms to encourage startups (the government’s goal is to foster 100 new biotechs by 2030). Singapore and South Korea have also supported biotech funds: for example, Singapore’s EDBI often anchors regional VC funds (such as a $200M South East Asia life science fund in 2024), and Korean conglomerates have started corporate VC arms in health. While no headline new fund came from those in early 2025, activity is ongoing beneath the radar.

Rest of World

Israel, known for healthcare innovation, saw its largest health-tech fund aMoon close at $660M in 2021 (altassets.net). In 2025, Israeli VCs (aMoon, Pontifax, etc.) remain active investors and likely preparing new raises, given strong deal flow in digital health and biology convergence in Israel. No new fund was announced yet, but the ecosystem is well-capitalized from prior funds. In India, biotech VC is still nascent but a few funds (like Bharat Innovation Fund, and global firms like Eight Roads) are investing in areas like biomanufacturing and genomics.

The Middle East, as mentioned, is more channeling capital outward or into building local R&D infrastructure (e.g. the new research centers in Abu Dhabi, NEOM’s biotech ambitions in Saudi).

Australia quietly had some venture raises too – e.g. Brandon BioCatalyst fund II closed AUD 300M in 2022 with government and pharma backing, continuing to fund Australian biotech startups in 2025. So globally, while the center of gravity is U.S./Europe, there’s increasing connectivity: funds are syndicated across borders (U.S. VC putting money in European funds, Asian LPs in U.S. funds, etc.), and new funds often have international mandates even if based locally (AN Ventures, DDF, etc.).

Continuation Funds and Secondary Solutions: Extending the Runway

A significant development in the private equity side of pharma is the rise of continuation funds – a mechanism by which a VC/PE sponsor can move one or more of its portfolio companies into a new vehicle (fund) to hold them longer, while giving existing investors an option to cash out. These have become mainstream across private markets, and biotech is no exception.

By 2024, as noted, GP-led secondaries (mostly continuation funds) reached ~$72 billion in transaction value, making up close to half of the $152B global secondaries market. Drivers include the lack of IPO exits (funds need more time for their companies) and LPs’ desire for liquidity in older funds. In biotech, where drug development timelines often exceed the 10-year fund life, continuation vehicles can be especially useful to back “crown jewel” assets through pivotal trials and commercialization rather than selling too early.

2025 is expected to see further growth in these transactions. Large firms are doing multi-asset continuations: e.g., Warburg Pincus held a first close of its first multi-asset continuation fund at $2.2 billion in Dec 2024 (though Warburg is multi-sector, it could include some healthcare assets). Mid-sized firms often opt for single-asset deals: e.g., in 2024 Gryphon Investors spun out a single company (in water treatment sector) into a continuation vehicle. In biotech, one could imagine a VC like Orbimed or Flagship taking a late clinical-stage company that isn’t IPO-ready and rolling it into a new fund with fresh money to carry it to approval.

We don’t have public confirmation of specific biotech continuation fund deals in H1 2025, likely because such processes are usually private. However, there were rumors of several being explored in 2023-25. For example, some speculated that RTW Investments might pursue a continuation vehicle for one of its gene therapy holdings, or that TPG could do so for certain life science portfolio stakes.

The net effect is that continuation funds have become an important tool to “extend the runway” for high-potential therapies. They bring in secondary investors who are often specialized secondary funds or institutional LPs looking for more seasoned assets. For the biotech industry, this trend can be a blessing: it means a promising drug doesn’t have to be sold off cheaply or shelved just because the original fund’s clock ran out. Instead, the company gets more time and money under largely the same management.

It does, however, raise questions about valuation transparency and governance (hence the importance of rigorous due diligence and fair pricing – even employing independent valuations or “AI” tools for analysis, as novel solutions like Robin AI suggest.

LPs have generally warmed to continuation funds, given the record dry powder in secondary markets waiting to be deployed. And interestingly, 2024’s downturn might have actually boosted this trend – many LPs couldn’t get out via IPOs, so the GP-led liquidity offers were appealing. If public markets recover later in 2025 or 2026, some of these continuation-backed biotechs might finally IPO or be acquired, delivering delayed gratification to both original and new investors. For now, it’s a bridging solution emblematic of this era.

Conclusion: A New Financial Ecosystem for Pharma Innovation

In the first half of 2025, even as biotech markets remained in a lull, we have witnessed the birth of new funds and models that will shape the next decade of pharma innovation. From massive funds wielding billions to shepherd mature therapies to nimble funds seeding start-ups in novel ways, the financing machinery is adapting to ensure that scientific progress doesn’t stall. The style of investment is indeed shifting – bigger funds, bigger bets, but also broader collaboration (with corporates, governments, philanthropies) and more creative tactics to derive value (continuation funds, special situations like Alis).

Several implications emerge

For biotech entrepreneurs, there may be fewer but more substantial funding sources available. If you are working on a validated program in a hot area (say, AI-enabled drug design or an obesity drug), you might tap into a mega-fund like Arch or Sofinnova for a $100M Series B. If you’re very early with just a cool idea, you might aim for a Curie.Bio or a seed-focused program. The middle ground is tougher – as the Wing VC partner said, series B stage for less proven teams is tricky (biospace.com). Here, the emergence of disease-focused funds (Vie Ventures, DDF) or regional funds (AN Ventures, Genesys) could fill some gaps, funding solid but perhaps more localized or specialized opportunities that big global funds might overlook.

For big pharmaceutical companies, the evolving VC landscape offers both a pipeline and a partner. They are co-investing via these funds (directly as Lilly did, or as LPs in many funds), effectively outsourcing some R&D by backing external innovation. We might expect more such arrangements – perhaps a Pfizer teaming with an AI-focused VC for a fund, or a consortium of pharmas launching a climate-tech and health fund (given sustainability and health intersect). Pharma’s participation also means startups need to be cognizant of strategic implications (e.g. taking Lilly’s money via the a16z fund might orient you towards a future Lilly acquisition or partnership).

Geopolitically, the funding is diversifying, which is healthy. Japan’s concerted effort and Europe’s sustained investor interest mean the biotech industry will remain global in flavor, not just reliant on Silicon Valley and Boston money. However, the U.S. continues to be the 800-pound gorilla in terms of capital raised and deployed.

One must note a caution: capital raising is cyclical, and many of the funds closed now were started in motion 1–2 years ago. If the macro environment stays challenging, the second half of 2025 and 2026 might see fewer new funds overall. PitchBook’s data already showed a huge drop in number of funds from 2021 to 2024 (biopharmadive.com). We’ve covered those brave or successful enough to close now – but numerous other venture groups have delayed fundraising or downsized targets. The industry could see consolidation in venture firms themselves.

On the positive side, innovation areas like gene therapy, neuroscience, immunology, and AI are still drawing money – but often targeted money. The presence of funds like DDF-2 for dementia means hope for traditionally underfunded diseases. And vehicles like Alis Biosciences mean efficiencies – recycling wasted capital to new science – which overall is good for the ecosystem’s sustainability.

In sum, the story of H1 2025 is one of adaptation and resilience in pharma financing. The players with established reputations raised even larger funds, ensuring that advanced clinical programs (think next-gen cell therapies, RNA medicines, etc.) won’t die on the vine for lack of capital. Meanwhile, new players with fresh ideas have emerged to support early innovation and neglected areas, keeping the flame of discovery alive. The world of biotech has always been high-risk, high-reward – but thanks to these new funds, many of those risks will be borne by deep-pocketed, patient investors who believe in the long game of drug development.

If there is a lesson, it might be this: innovation in biotechnology finds a way to get funded. It may not be the irrational exuberance of 2021, but in a more sober 2025, money is still talking – just more discriminatingly. The next Moderna or BioNTech could well be incubating in a Curie.Bio cohort, financed by a Sofinnova, guided by a Vie Ventures advisor, or spun out via an Alis rescue. For patients awaiting new therapies, these financial maneuvers behind the scenes today could yield life-changing medicines tomorrow. The purse strings are new, but the goal remains the same – to advance healthcare breakthroughs, and, of course, earn a handsome return in the process.

Member discussion