Pharma’s Perennial Patent Cliff: Crisis or Routine Cycle?

The Next Big Patent Cliff Looms

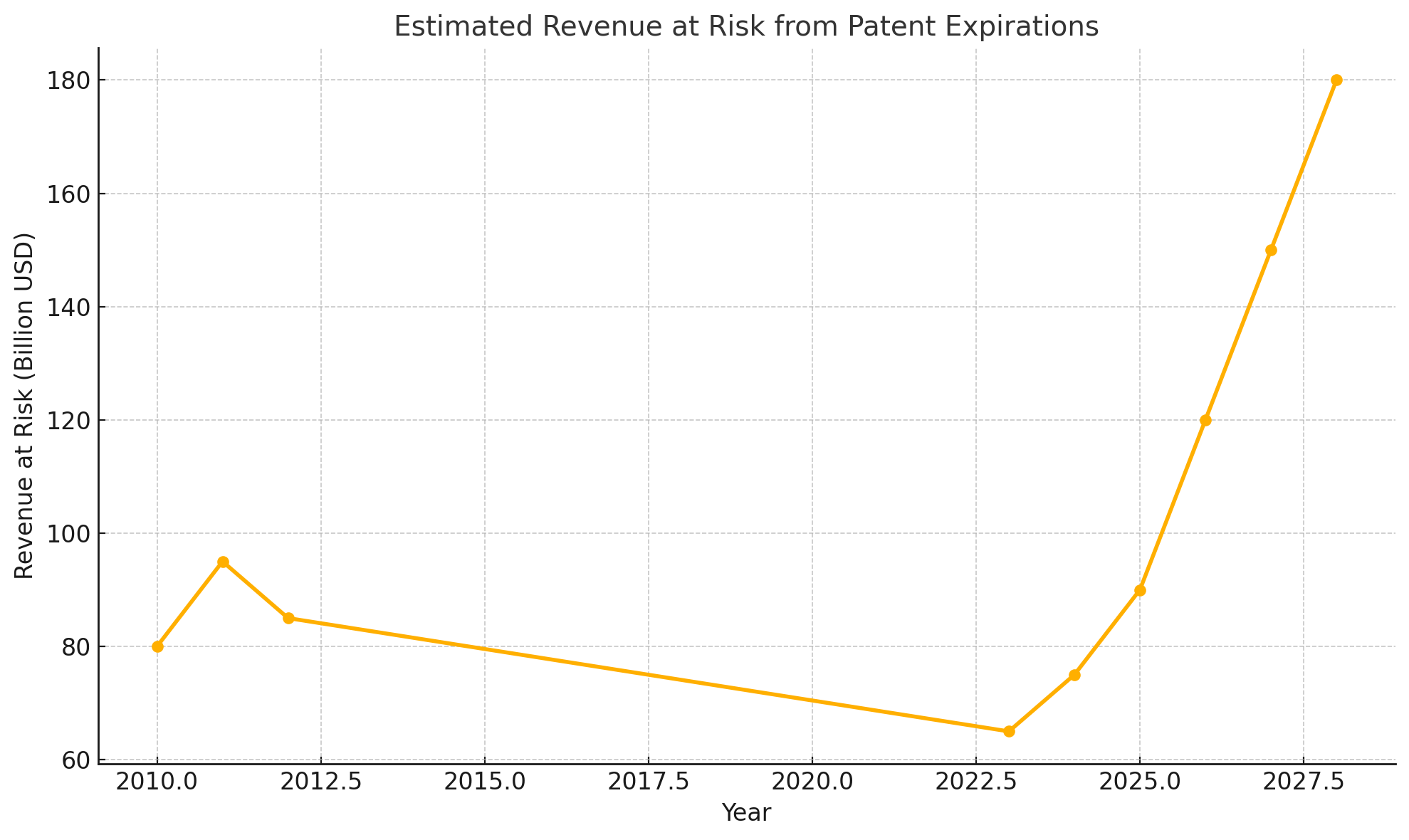

Pharmaceutical investors are once again bracing for what industry insiders ominously dub a “patent cliff.” In 2027-2028 alone, drugs accounting for roughly $180 billion in annual sales – nearly 12% of the global pharma market – will lose patent protection. This wave includes some of the world’s top-selling medicines. Merck’s immunotherapy Keytruda, for example, earned $29.5 billion last year, but its exclusive run ends in 2028. Not surprisingly, Merck’s stock price has slid in anticipation – down about 35% over the past year – as investors fret over how the company will replace such a cash cow. One analyst warns that Merck faces a “massive revenue gap” it “cannot fill…with just one drug”. Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer likewise confront 2028 expirations for blockbuster therapies (moomoo.com).

Patent expirations are visible years in advance, yet they still manage to spook markets. “Investors often lack foresight” about these cliffs and can be “surprised” when the day finally arrives, notes Tim Opler of Stifel’s healthcare group. The market’s short-termism means pharma companies feel intense pressure to scramble for replacements once the end of exclusivity nears. The revenue wipeout can indeed be dramatic: when a drug’s patent expires, cheaper generic or biosimilar copies can rapidly erode billions in sales for the original producer. This harsh reality reflects an inherent tension in drug economics – high costs to innovate, but low costs to imitate. Society grants drugmakers temporary monopolies (usually ~20 years from patent filing) as a reward for innovation, but once that period ends, competition drives prices down fast (moomoo.com).

Yet amid the dire headlines and stock jitters, industry veterans might respond with a wry smile. They’ve seen this movie before. In fact, the coming patent cliff is anything but unprecedented – it’s the latest repeat of a boom-and-bust cycle that has defined Big Pharma for decades. The key question is whether this cliff is truly different or simply another steep hill the industry will successfully climb, as it has in the past.

A Familiar Cycle: We’ve Been Here Before

This isn’t the first time pharma’s sky was said to be falling. A decade or so ago, around 2010-2012, Big Pharma weathered another major patent cliff. Back then, a huge cohort of traditional “small-molecule” drugs – Lipitor, Plavix, Zyprexa, and many other household names – lost exclusivity in quick succession. “At the start of the last decade, big pharma was getting smaller,” one analysis noted, as years of patent-fueled growth suddenly gave way to generic competition.

The impact was sharp enough that it “temporarily stalled the relentless upward march” of U.S. drug spending (biopharmadive.com). Lipitor, Pfizer’s famed cholesterol pill and once the world’s top-selling drug, saw U.S. sales plunge from nearly $11 billion in 2010 to just $4 billion in 2012 after generics hit. Pfizer’s total revenue fell by almost $9 billion over that period. Similar patent expiry shocks hit Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca and others, earning 2011-2012 the moniker “the patent cliff” in pharma lore.

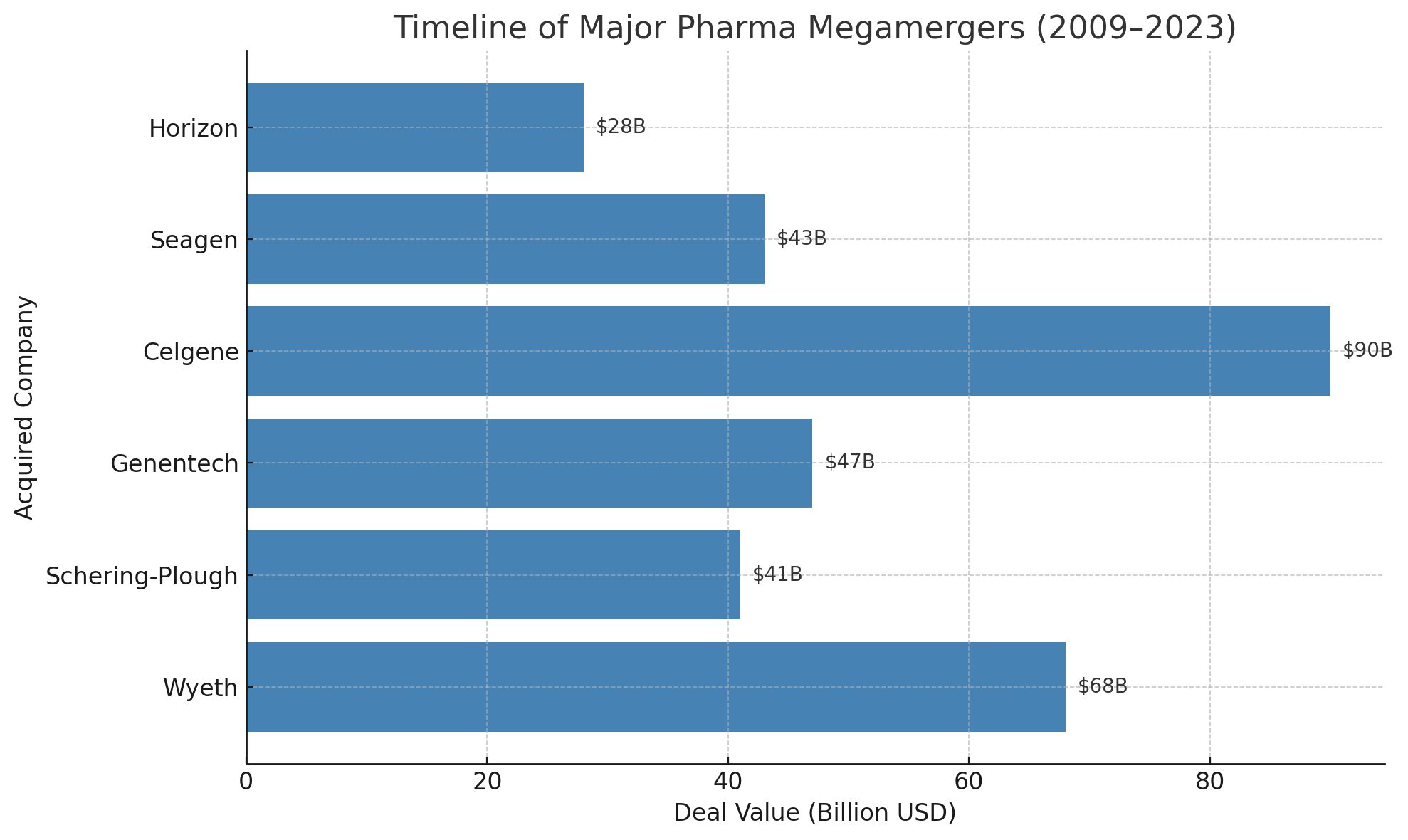

Industry strategists responded with playbooks that now feel very familiar. Many companies chose to merge or acquire rivals to survive. In 2009, anticipating the onslaught of expirations, Pfizer bought Wyeth for $68 billion and Merck absorbed Schering-Plough for $41 billion. A few years later, as the cliff’s impact peaked, Roche acquired Genentech and Sanofi bought Genzyme. These megamergers helped companies bulk up pipelines and diversify revenues, cushioning the blow of losing their older cash cows. Internally, firms also slashed costs, restructured, and doubled down on research of new therapies. In short, pharma did what it always has – adapted.

Importantly, the apocalyptic predictions of a decade ago proved overblown. Yes, Big Pharma’s sales and profits dipped in the early 2010s, but they hardly “destroyed” the industry. After a brief lull, global drug spending resumed its climb as new medicines – from cancer immunotherapies to Hepatitis C cures – came to market. By the late 2010s, many pharma companies were larger and more profitable than ever. The lesson: patent cliffs are painful but survivable, especially for firms that plan ahead.

The Biosimilar Scare That Wasn’t

Even as the dust settled from the small-molecule cliff, a new specter arose: biosimilars. These are the generic equivalents for complex biologic drugs (medicines made from living cells, such as antibodies or proteins). For years, drug makers openly dreaded the onslaught of biosimilar competition – fearing it would undermine the biotech revolution that had led to drugs like the antibody Humira or the cancer-fighting Keytruda. “For years, drug makers have feared” this scenario, Quartz observed in 2015, when the FDA finally approved the first true biosimilar in the United States (qz.com).

(Europe had allowed biosimilars even earlier, approving its first in 2006) Industry rhetoric warned that cheaper copies of biologics could wreak havoc on profit margins and upend pharma’s business model.

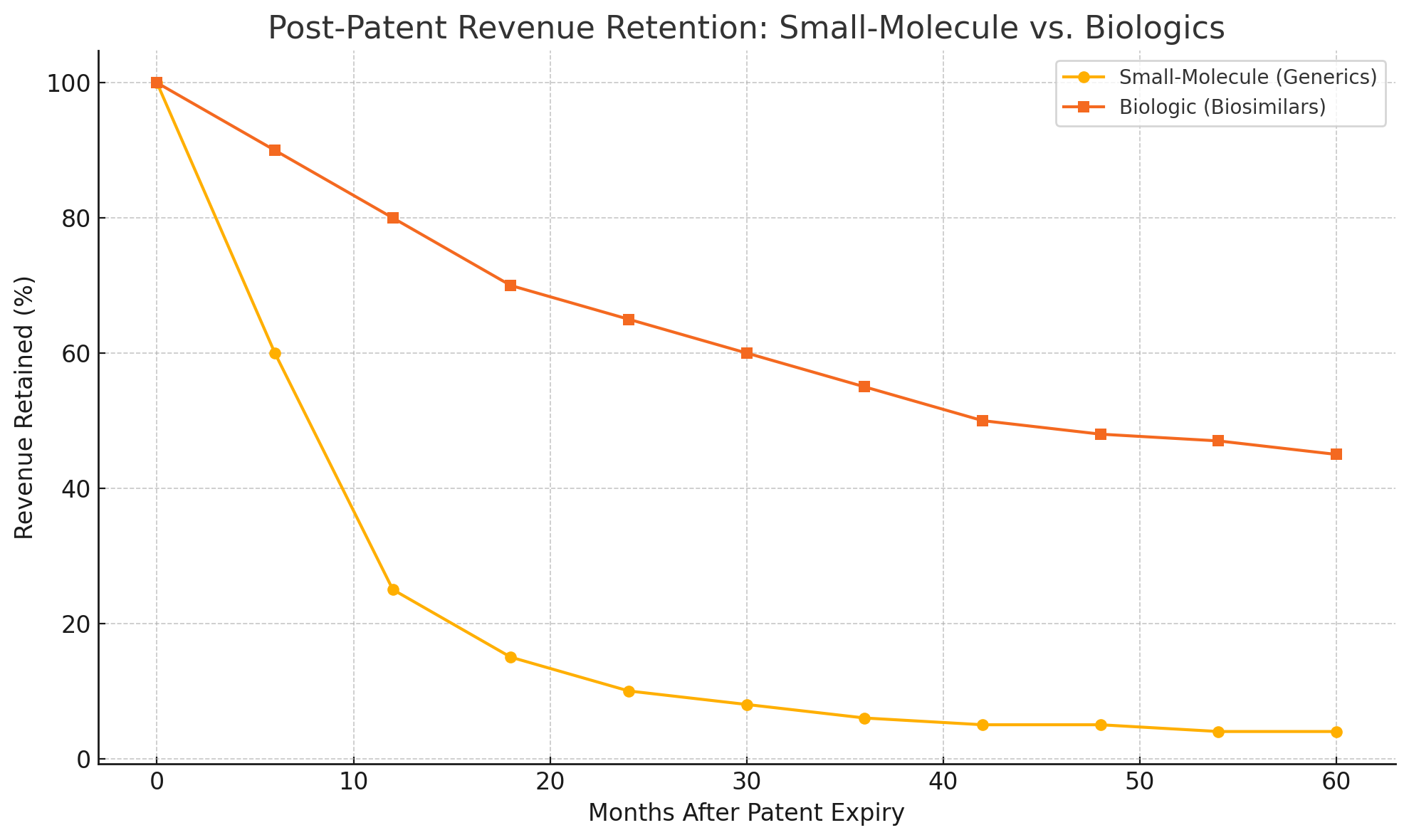

What happened next was more of a whimper than a cataclysm – at least initially. Early biosimilars rolled out slowly and faced hurdles, especially in the US. Biologic drugs are far more complex than pills, so copying them isn’t as straightforward. Regulators created special pathways for biosimilars, but manufacturers and healthcare providers were cautious.

In the US, unlike with traditional generics, pharmacists cannot automatically substitute a biosimilar for a brand-name biologic unless it meets extra “interchangeable” criteria. This meant uptake was gradual. Furthermore, only a trickle of biosimilars hit the market in the late 2010s, limiting their impact. Indeed, early on biosimilars didn’t dent prices as much as payers hoped, in part because there were so few of them and brand-name companies fought hard to defend their turf. Some pharma companies negotiated rebate deals and contracts to blunt biosimilar competition, ensuring insurers stuck with the brand in exchange for discounts (biopharmadive.com).

Consider AbbVie’s Humira, the world’s best-selling anti-inflammatory drug. Its primary patent expired in 2016, and biosimilars quickly entered European markets – yet in the U.S., Humira kept its monopoly for another seven years through legal maneuvers. By 2020, AbbVie was still charging roughly $77,000 per patient annually and reaping $16 billion in U.S. Humira revenue.

A “patent thicket” of 132 secondary patents (on manufacturing methods, formulations, etc.) helped delay U.S. biosimilars until 2023. Rival companies complained and even sued over this evergreening tactic, and American politicians howled that Humira exemplified pharma’s abuse of the system (moomoo.com).

(Notably, a federal court ultimately upheld AbbVie’s patents, and efforts to legislatively curb such “patent jungles” are ongoing.)

Only in 2023 did Humira finally face U.S. biosimilar competition – and even then, the decline has been gradual. By mid-2023, multiple Humira copycats launched, yet AbbVie is forecast to retain a sizable portion of its U.S. sales into 2024. This underscores a crucial point: biosimilars often erode sales more slowly than old-fashioned generics.

A conventional small-molecule drug losing patent can see 80–90% of its sales vanish within months, as dozens of generic pills flood the pharmacy at prices 90% below the brand. Biologics, by contrast, are harder to replicate and usually have fewer direct competitors. Their imitators (biosimilars) typically launch at only a modest discount – perhaps 50% of the brand price, not a mere 10%.

Doctors may be hesitant to switch patients who are stable on a brand-name biologic, and some biosimilars aren’t deemed interchangeable anyway. As a result, the “cliff” for biologic drugs is more like a rolling hillside. Market analysts estimate that for blockbuster biologics, sales might decline 30–70% in the first year post-patent, rather than the near-total collapse seen with pills.

Columbia University’s Frank Lichtenberg even predicts the 2027-28 patent cliff “could be more like a steep hill,” taking perhaps five years for sales to drop by three-quarters (moomoo.com). In other words, the fall is real – but it may not be a sheer drop.

None of this is to suggest pharma welcomes the biosimilar era. On the contrary, the industry has been fighting on multiple fronts to soften the blow. In addition to patent thickets, companies deploy trade-secret manufacturing tricks, reformulate drugs (for instance, testing a new injection version of Keytruda that could earn a fresh patent), and sometimes shift the battleground to insurers. Big firms have reportedly offered steep discounts on bundles of brand-name drugs if insurance middlemen agree to exclude a new generic rival from coverage.

Such maneuvers can buy a brand drug a few extra protected years, even after official exclusivity lapses. Regulators are starting to push back – European competition authorities are scrutinizing “unfair” patent gaming, and in the U.S., recent administrations have sought faster biosimilar approvals and easier substitution to speed competition.

In 2025, the government even empowered Medicare to negotiate prices on certain older drugs, effectively curbing profits on some products a bit earlier than their patent expirations. These policy shifts add new uncertainty for drug makersm. Still, the historical pattern holds: each time a feared patent cliff approaches, pharma finds ways to stay profitable, whether by innovating, litigating, or lobbying – usually all of the above.

Adaptation: Pharma’s Survival Instincts

Why has no patent cliff yet spelled doom for Big Pharma? Because the industry adapts, time and again. The fundamental challenge of patents – finite exclusivity on a lucrative product – is baked into pharma’s DNA. Drug companies know from the day they launch a new therapy that a countdown has begun. The smarter firms start planning replacements long before revenues hit zero.

As economist Bhaven Sampat observes, the patent system is a “blunt tool” for incentivizing innovation – it “overcompensates” some inventions and “undercompensates” others – but it’s the system we have (moomoo.com). Pharma executives have become adept at managing this blunt instrument’s side effects.

One tried-and-true strategy is using today’s cash to buy tomorrow’s pipeline. M&A is practically a tradition in lean times. When a revenue gap yawns, Big Pharma often opens its wallet to acquire smaller biotech companies with promising drugs. In the run-up to the 2010s patent cliff, this approach led to the megamergers noted earlier. And it’s happening again. By early 2023, industry analysts at EY estimated that large pharmaceutical companies had a staggering **$1.3 **trillion in “firepower” for acquisitions (moomoo.com).

After a brief lull in 2024, deal-making is expected to accelerate as the 2027 cliff nears. Companies are hunting for the “Goldilocks” acquisition targets – not so large as to invite antitrust woes, but substantial enough to deliver a blockbuster or two. Recent years have already seen big buys: Pfizer’s $43 billion purchase of cancer biotech Seagen, Amgen’s $28 billion takeover of Horizon Therapeutics, and Merck’s $11 billion deal for Acceleron Pharma, to name a few. Every pharma giant is effectively shopping for new hits. Merck itself has been rumored to be close to acquiring biotech Verona Pharma for $10 billion – explicitly framed as a move to “address the Keytruda patent cliff,” according to reports.

If mega-mergers are less in vogue now (in part due to tougher regulators and integration headaches), many big companies are instead striking targeted licensing deals and partnerships. A notable new wrinkle is the focus on China. A decade ago, Western pharma barely considered Chinese biotech innovations; now, they’re actively courting them. In the past year, licensing deals that give Western firms rights to Chinese-developed drugs have reached $35 billion in value.

The attraction is obvious: cutting-edge science at lower upfront cost. A cancer therapy invented in Shanghai might be licensed by a U.S. pharma for global development, offering a fresh revenue stream. Investors like Nanna Lüneborg of Forbion Capital call China’s rise “phenomenal,” amazed by the scale and quality of drugs emerging from Chinese labs. However, relying on overseas innovation carries its own uncertainties – from geopolitical risks to the chance an unknown Chinese rival undercuts a Western product in the future. Even so, in the scramble to fill pipelines, no stone is left unturned. The looming patent cliff has effectively globalized pharma’s R&D search.

Meanwhile, companies are also investing heavily in their in-house R&D to create the “next big thing” organically. Merck, for example, touts that it now has the largest, most diverse pipeline in its history, with its late-stage drug candidates tripling since 2021. The company pegs the revenue potential of those pipeline drugs at $50 billion by the mid-2030s. Similarly, others like Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca are pouring billions into research areas like mRNA technology, gene editing, and next-generation antibodies in hopes of spawning whole new classes of therapies.

The reality, however, is that R&D is a high-risk gamble; for every Keytruda or Humira, countless hopefuls fail in trials. Some analysts worry that pharma’s innovation engine isn’t as efficient as it used to be – returns on R&D investment have been declining over the past decade. In fact, a hard truth of the patent cliff is that if robust innovation had kept pace, the cliffs wouldn’t be so steep.

The current predicament in part reflects an innovation gap in the mid-2010s that left fewer new blockbusters to take the baton. Thus, companies are now racing to improve R&D productivity, often via smarter use of data, AI, and more agile trial designs.

Finally, when all else fails, pharma can rely on its deep pockets and marketing muscle to maximize whatever new products do launch. Some industry watchers predict an era of “fewer mega-blockbusters and more specialized therapies” ahead. This means big firms will need to execute more product launches, more frequently, to make up the same revenue. That is a daunting shift – but large drugmakers like Pfizer, Novartis, and Merck have been gearing up their commercial engines accordingly. These companies know that being complacent with a few star products is not an option when each star eventually fades.

No Cliff Too Big?

So, is the “patent gap” truly real? Yes and no. On one hand, the numbers don’t lie: over the next five years, pharma companies will lose substantial revenue as a historic crop of blockbusters goes off-patent. Some individual firms could see half their current revenues at risk by 2030, a serious challenge by any measure.

Patients and health systems, for their part, stand to benefit from cheaper generics and biosimilars entering the market, potentially saving tens of billions of dollars overallqz.com. In that sense, the patent cliff is quite real – it’s a feature of the pharmaceutical landscape that resources shift from innovators to imitators, ideally to the wider public’s gain.

On the other hand, the direst predictions of industry collapse have consistently been proven false. Every time a patent cliff nears, the refrain is the same: “This will destroy pharma’s ability to innovate. The sky is falling.” And every time, pharma adapts and survives. After the last big cliff, the industry emerged with new products (and new profits) within a few years. When biosimilars threatened to upend biologics, companies adjusted – and many biologic makers, like Amgen and Novartis, even turned the challenge into opportunity by launching biosimilars of their own.

In reality, Big Pharma’s business model has always been a cycle of invent, reap rewards, reinvest, and reinvent. Yes, companies can become “victims of their own success” – a blockbuster cure today means a patent cliff tomorrow – but thus far they have proven remarkably capable of climbing out of those valleys.

This time around, the cliff is taller than before, and some new twists (such as a larger share of biologics, and more aggressive political scrutiny on drug pricing) add uncertainty. Some analysts have called the coming wave “tectonic” in magnitude.

It will not be painless – expect some companies to stumble, and perhaps a round of consolidation and belt-tightening across the sector. But history suggests the patent cliff of the late 2020s will be a hurdle, not a death knell. As one industry blog put it, overcoming such obstacles is “nothing new” for life science companies. The innovative engines of pharma are not about to grind to a halt; if anything, the looming revenue gap is spurring a renewed urgency to develop the next generation of therapies. In the end, patients may benefit from that urgency as much as shareholders do.

In summary, the patent cliff is real – but so is Big Pharma’s ability to adapt. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. The patent panic of 2025 will likely fade into the progress of 2030, just as previous ones have before.

Member discussion