Recursive Evidence and the Fat-Tailed Risk of HTA Circularity

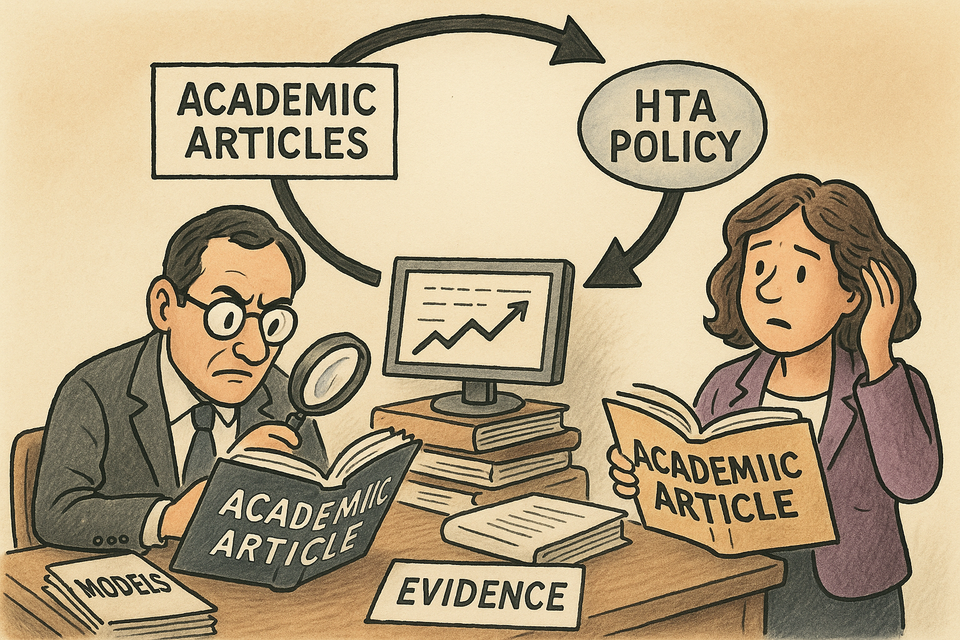

It begins, as all good policies do, with a peer-reviewed article. A study from 2013 estimates the cost of a hospital stay for rheumatoid arthritis. The figure is well-argued, methodologically neat, and printed in an impeccable journal. The number is then cited in a 2017 HTA submission. That submission is referenced in a 2019 policy document. In 2022, a new cost-effectiveness model uses the 2019 document to justify the same number. And by 2025, one can quite sincerely write that this figure has been "established in the literature."

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ Academic article (A) cites B │

└─────────┬───────────────────┘

│

│ cites

▼

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ HTA submission uses A's X │

└─────────┬───────────────────┘

│

│ based on

▼

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ Reimbursement policy uses X │

└─────────┬───────────────────┘

│

│ cited in

▼

┌─────────────────────────────┐

│ New article B cites policy │

└─────────┬───────────────────┘

└───────┐

▼

(back to A)—loop continues

Thus the circle is complete. No one involved has done anything wrong. Each participant is citing in good faith, armed with proper citation style and regulatory deadlines. But what has quietly taken place is a transformation of assumption into truth, and truth into policy.

The phenomenon is not new, but it is accelerating. Health technology assessment (HTA), once a niche concern of public health bureaucrats, is now a central actor in global pharmaceutical pricing. As of 2025, more than 80 countries operate HTA functions. But their procedures are deeply reliant on academic literature. And herein lies the rub: HTA doesn't cite reality. It cites studies that cite studies that cite something from 2003.

Citation as Ritual

This recursive loop is not just epistemically fragile, it's also deeply institutionalised. HTA bodies expect cost and utility inputs to be backed by published references. Journals require novelty over replication. Consultancies, rewarded for speed, pull parameter estimates from past submissions. It is a system optimised for momentum, not accuracy. Literature becomes the data. Models become tradition.

The problem is not merely academic. Real reimbursement decisions flow from these models. If the assumed cost of a condition is overstated, manufacturers can argue for higher price ceilings. If it's understated, patient access may be delayed or denied. A small parameter, like the utility decrement of an adverse event, can swing millions in payer spend.

Taleb's Ghost in the Model

Enter Nassim Nicholas Taleb, whose ghost stalks this discussion. In his work on fat tails, Taleb warns that complex systems often hide their biggest risks in the assumptions we least scrutinise. An HTA model with 40 parameters doesn't just have 40 uncertainties. It has compound uncertainty: uncertainty squared.

Taleb distinguishes between measurable randomness (like dice rolls) and epistemic uncertainty (like modelling hospital costs in Bulgaria). The former can be managed with statistics. The latter cannot. Worse, attempts to treat epistemic uncertainty as mere variance conceal systemic risk. We assume the inputs are wrong within a narrow band, when in fact they may be wrong by orders of magnitude.

He also introduces the ludic fallacy: mistaking the clean logic of games for the messiness of the real world. HTA is riddled with this. A model may use symmetrical distributions, tidy time horizons, and preference scores derived from a UK survey in 1997. But reality is discontinuous. Policies shift. Prices renegotiate. Hospital practices evolve. And yet, the model marches on.

The Feedback Loop that Hardens Error

Recursive citation would be a curiosity if it lived in journals alone. But it doesn't. It infects the very policies meant to govern real-world markets. Once a number enters a reimbursement decision, it gains bureaucratic legitimacy. Future submissions can cite it as established policy. It becomes very difficult to dislodge. In this way, assumptions harden into thresholds. Estimates fossilise into price bands.

In Germany, reference pricing can be indirectly informed by published cost ranges. In the UAE, central tender prices may cascade through formulary tiers. In France, cost-effectiveness thresholds (though never explicit) are often reverse-engineered from earlier appraisals. Around the world, HTA is increasingly the foundation for not just pricing, but for access itself.

And yet, even in 2025, most HTA submissions cite cost estimates that are at least five years out of date. Some are a decade old. Many are based on care standards that no longer apply.

Data Exists, But It Is Not Cited

This would be excusable if there were no better data. But that excuse is rapidly vanishing. As of 2025, most European countries publish regular updates to procurement prices, DRG tariffs, and reimbursement schedules. The German Lauer-Taxe, Italy's AIFA database, and France's CEPS reporting all offer contemporary figures. The European Health Data Space (EHDS), now ratified, is beginning to standardise access across the EU. And commercial sources like IQVIA, Komodo, and Clarivate make real-world utilisation data available at scale.

But researchers rarely cite these. Why? Partly because government portals change URLs. Partly because journals prefer references to indexed papers. Mostly because no one gets promoted for tracking down the June 2023 version of the Belgian hospital price schedule.

A Kind of Beautiful Irrelevance

This creates a curious form of elegance. HTA models are intricate, internally consistent, and methodologically sound—but irrelevant. They compute QALYs to four decimal places while missing a 30% change in underlying costs. They include tornado diagrams but not last year's real procurement price.

The result is not just fragility. It is policy drift. If multiple HTA decisions are based on recursive estimates, the system slowly disconnects from reality. Budget impact becomes misaligned. Access decisions become miscalibrated. And the feedback loop reinforces itself: outdated assumptions become the benchmark for future reviews.

Can the Loop Be Broken?

Yes, but only with institutional effort. The first step is to normalise the use of real-world data in academic work. Government sources should be citable, even if not peer-reviewed. Journals should allow data provenance statements that point to spreadsheets, not just DOIs. Reviewers should ask whether a number is still true, not just whether it was ever published.

Second, HTA bodies can introduce audit cycles. Parameters older than three years should trigger a flag. Inputs that differ significantly from current administrative data should require justification. Agencies could maintain live parameter libraries—modular, curated, and updateable.

Third, we need to reward antifragility. A model that adjusts to new data should be valued over one that merely extends a past framework. Replication studies, cost recalibrations, and sensitivity tests on real-world variance should be publishable acts, not grey literature.

Talebian Optimism

Taleb, curmudgeonly as he can be, is ultimately optimistic. He believes systems can be designed to benefit from disorder. HTA can do the same. Rather than fearing the volatility of real prices or epidemiological shifts, models can ingest them. Updating a model need not be an admission of error. It can be a feature.

In fact, the best models will learn. They will revise. They will throw away that 2013 paper on RA hospital costs and pull the Q4 2024 figures from Spain's official DRG database instead. They will cite live data feeds, triangulate with claims analytics, and give regulators something they have not had in years: a model that reflects the present.

Conclusion: Toward a Data-Rich Rationality

Recursive citation is a rational response to irrational incentives. It is the product of a system that prizes polish over precision, elegance over empirical truth. But the costs are now visible. Policy is being built on estimates that no longer match the world they intend to govern.

HTA must evolve. Not to abandon literature, but to triangulate it. Not to reject models, but to debug them. Not to shame researchers, but to liberate them from the tyranny of citation.

To quote Taleb once more: "Don’t tell me what you think, show me your portfolio." In HTA, the equivalent might be: "Don’t tell me what you cited. Show me where the number came from."

Member discussion