South Korea’s Innovation Leadership at a Crossroads (2025 and Beyond)

South Korea’s rise from a war-torn nation in the 1950s to a global technological powerhouse is nothing short of extraordinary. However, as we approach 2025 and beyond, the challenge is to ensure that the big bets which fueled past success have not come at the cost of future innovation leadership (weforum.org, intralinkgroup.com). In other words, Korea must balance the strengths of its established industries and conglomerates with the agility and creativity of new innovators, so that today’s achievements do not hinder tomorrow’s breakthroughs.

This report takes a deep dive into South Korea’s current innovation landscape – examining its historical “bet” on conglomerates, the emergence of startups, the global technology race in areas like AI, and innovative financing solutions like IP (intellectual property) finance. We will critically assess whether mechanisms such as IP finance can bridge the funding gap facing many Korean startups, and what more is needed to secure South Korea’s future as an innovation leader.

1. From Miracle on the Han to Innovation Nation: A Legacy of Bold Bets

South Korea’s Economic Miracle and Its “Bet” on Conglomerates: In the latter half of the 20th century, South Korea engineered one of the fastest economic transformations in history, often referred to as the “Miracle on the Han River.” With scant natural resources, the country bet heavily on its people and industrialization, prioritizing education and export-led growth (weforum.org).

By partnering government policy with a select few “national champion” companies, South Korea fostered the rise of giant family-led conglomerates known as chaebols (weforum.org). These chaebols – firms like Samsung, Hyundai, LG, and SK – became the engines of growth, propelling Korea into global leadership in semiconductors, consumer electronics, automobiles, shipbuilding, and more (carnegieendowment.org).

This strategy paid off handsomely in making South Korea an economic powerhouse. Today, Korea is the world’s 11th largest economy and 5th largest exporter. Its flagship companies hold dominant positions: Samsung and SK Hynix produce some of the world’s most advanced semiconductors, Hyundai Motor is a top global automaker, and Samsung/LG lead in displays and appliances (carnegieendowment.org).

he country has also gained soft power through the global popularity of K-pop, K-drama, and other cultural exports, further elevating “Brand Korea” on the world stage (carnegieendowment.org). In short, South Korea’s big bet on building an industrial economy led by mega-corporations and heavy manufacturing succeeded in lifting the nation into prosperity and technological prowess.

The Side Effects – A Double-Edged Sword: However, this development model also had side effects. The dominance of conglomerates led to uneven distribution of wealth and economic power, with small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and startups historically playing a secondary role (weforum.org).

South Korea became technologically strong in hardware and manufacturing, but until recently it lagged in fostering the kind of nimble startup culture seen in Silicon Valley. Innovation tended to be top-down and incremental, focused within chaebol R&D labs, rather than disruptive and bottom-up. Critics have long worried that an economy so reliant on a few giants could stifle entrepreneurship and risk-taking, potentially causing Korea to fall behind in the era of rapid digital disruption.

Indeed, as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) gains speed – characterized by AI, software, biotech, and platform-based business models – the old formula is being tested. “South Korea is now at a critical inflection point,” observes a World Economic Forum report (weforum.org). The country’s strength in manufacturing and hardware, led by large corporations, must now be balanced with an ability to foster digital innovation and startups, since in 4IR “innovative disrupters could overthrow strong incumbents” (weforum.org).

The big question is whether Korea’s past bet on conglomerates can evolve to accommodate a more dynamic, open innovation ecosystem. As one analysis framed it, the challenge of 2025 and beyond is to ensure that Korea’s earlier bet hasn’t come at the cost of its future innovation leadership. This means South Korea must prevent complacency from eroding its competitive edge, and must nurture new growth engines even as it maintains its current strengths (weforum.org, intralinkgroup.com).

2. The Changing Landscape: Startups on the Rise

Encouragingly, the tide has been turning. In the past decade, South Korea’s startup scene has blossomed, signaling a significant shift in mindset and policy. Government support and a new generation of entrepreneurs are helping to diversify the innovation ecosystem beyond the chaebols.

Policy Push for Startups: Recognizing the need for a more balanced approach, the Korean government launched initiatives to incubate startups and SMEs. A pivotal move was the creation of the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS) in 2017, elevating startup development to a cabinet-level priority (weforum.org). Programs like TIPS (Tech Incubator Program for Startups) were introduced – a government-backed incubator/accelerator that matches promising startups with funding and mentorship (weforum.org).

These efforts began to bear fruit. By 2021, venture investments in Korean startups reached ₩7.7 trillion (~$6.4 billion), a 78% year-on-year growth. For perspective, that marked a huge jump from just a few years prior; 2020 saw roughly ₩4.3 trillion, meaning Korea’s venture funding nearly doubled within a year amid a global startup boomg. This growth in venture capital was accompanied by a surge in new startups and job creation – the number of new jobs created by Korean startups in 2021 actually exceeded those created by the four largest conglomerates (Samsung, Hyundai, SK, LG) combinedweforum.org. Such statistics underscore how significantly the entrepreneurial sector has expanded in a short time.

Cultural Shift and Corporate-Startup Synergy: Just as important as government money has been a cultural shift in attitudes toward entrepreneurship. Not long ago, the most coveted career paths for Korean talent were entering a top chaebol, a government post, or professional fields like medicine and law (weforum.org). Founding or joining a startup was seen as far riskier and less prestigious. But this is changing. Surveys of successful entrepreneurs reveal that nearly one-third of Korean startup founders are people who left stable jobs at conglomerates to strike out on their own, and this phenomenon is more pronounced among younger professionals (weforum.org).

In other words, a new generation is increasingly willing to embrace risk and innovation, rather than pursuing the traditionally “safe” careers. This shift in mindset has been critical in fueling the startup boom.

Moreover, instead of viewing each other as adversaries, startups and conglomerates in Korea are finding synergies. Many large corporations have set up corporate venture capital (CVC) arms or accelerator programs to invest in and partner with startups. For example, SK Telecom spun out and funded an AI startup (MakinaRocks) started by its former employees. Conglomerates see that startups can bring agility and novel ideas, whereas startups can benefit from the corporates’ resources, scale, and industry experience.

“Active participation from major corporates to nurture and collaborate with startups is pivotal,” says Andre Yoon, CEO of MakinaRocks, noting that large firms opening doors to entrepreneurs allows new technologies to flourish where they would otherwise have been siloed inside big companies (weforum.org). The result has been an emerging open innovation culture, with more fluid movement of talent and ideas between big companies and startups.

Notable Successes: Several Korean startups have made international waves, proving that homegrown innovation can succeed globally. For instance, online webtoon (digital comics) platforms from Korea have gained worldwide users, the edtech company Pinkfong (of “Baby Shark” fame) became a global children’s brand, and entertainment startup HYBE (formerly Big Hit Entertainment) turned BTS into a global phenomenon while pioneering new music business models (weforum.org).

On the tech front, Korea has produced unicorns (startups valued over $1B) in sectors like e-commerce (Coupang, which listed on the NYSE), gaming, fintech, and AI. A World Economic Forum piece updated in 2025 lauds that “Startups in South Korea are thriving”, crediting supportive policies and the entrepreneurial mindset shift for creating a more vibrant innovation hub (weforum.org).

All these developments indicate that South Korea’s innovation ecosystem is broadening. The country is no longer solely dependent on a handful of conglomerates for innovation; an increasingly robust cast of startups and scale-ups are contributing to new growth.

However, this transition is still very much a work in progress, and it faces headwinds – particularly in financing, which we will examine in depth in later sections. Before that, it’s important to understand South Korea’s position in the global technology race to appreciate why sustaining innovation leadership is such a critical challenge post-2025.

3. Competing in the Global Tech Race: AI as a Bellwether

In the realm of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), South Korea finds itself in an intense global race, primarily against the United States and China. The outcome of this race will heavily influence future economic leadership. Korea has world-class R&D capabilities – it leads the world in R&D investment as a percentage of GDP (around 4-4.5%) and boasts cutting-edge hardware industries (itif.org). Yet, there are warning signs that Korea’s innovation momentum could be slowing relative to its rivals in certain 21st-century domains.

AI and Digital Innovation: Korea at a Crossroads: AI is often called the “electricity” of the new age – a general-purpose technology that will transform every industry. South Korea recognized AI’s importance early, launching a national AI strategy and investing in initiatives like AI hubs and data centers. For example, the government built a national AI Data Center in Gwangju as part of an AI cluster project. Korean tech giants like Naver and Kakao have developed their own large language models (e.g. HyperCLOVA), and numerous startups (e.g. Upstage, Scatter Lab) are active in AI applications ranging from language to vision. In 2021, private investment in Korean AI startups totaled approximately $2.76 billion, showing a growing ecosystem (cset.georgetown.edu).

Despite these efforts, analysts note that South Korea is still punching below its weight in AI relative to the U.S. and China. One metric, the “2023 Global AI Innovation Index,” indicated that Korea significantly lags the U.S. and China in AI innovation (chosun.com).

An article in Business Korea bluntly stated, “While China has grown to a level that threatens the United States in the AI field, South Korea remains stagnant” (businesskorea.co.kr). The Korean government’s budget allocations to AI have faced scrutiny as well. In late 2023, budget cuts prompted concern that Korea was falling behind in the global AI investment race.

To put it in perspective, the scale of AI investment in the U.S. and China far outstrips Korea. The U.S. tech industry – powered by giants like Google, Microsoft, OpenAI and countless startups – invests tens of billions annually in AI R&D and commercialization. China, following its “Next Generation AI Plan,” has poured massive resources into AI startups, data centers, and talent, producing AI champions like Baidu, Alibaba, Huawei (for AI chips), and a burgeoning cohort of AI startups. Korea’s total AI investment (public + private) is a fraction of these sums, and this disparity has raised alarms domestically (businesskorea.co.kr).

Compounding the issue are regulatory and structural hurdles within Korea. A 2025 report by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF) argues that Korea’s regulatory framework – historically very prescriptive (so-called “positive regulation”) – is ill-suited for the fast-moving AI era (itif.org). For instance, Korean companies have sometimes been unable to launch new AI-driven services because regulators demand that laws explicitly permit them first, which slows down innovation.

The ITIF report notes that this approach “freezes innovation until regulatory frameworks catch up,” whereas competitors (like U.S. firms) can launch services and iterate faster under more flexible “negative” regulatory systemsitif.org. The result: Korea risks losing out in areas where first-mover advantage is critical, such as AI-driven platforms (itif.org). Indeed, ITIF highlights that despite Korea’s high R&D spending, its overall innovation ecosystem shows signs of deterioration: major platform companies lost over $50 billion in market value (due to stagnation), and Korea ranks near the bottom among OECD countries in perceived startup opportunities. These are red flags that Korea’s innovation leadership is not guaranteed going forward.

Signs of Progress and Collaboration Needs: On the positive side, Korea’s strength in underlying hardware (e.g. memory chips, 5G infrastructure) is a valuable asset in AI. Korean firms like Samsung are investing in AI chips, neuromorphic processors, and partnering with global AI players (Samsung supplies cutting-edge memory and is researching next-gen AI semiconductors).

SK Hynix and Samsung’s dominance in memory remains crucial since AI is data-intensive (though ironically, as one Korean report pointed out, extremely efficient new AI could reduce demand for high-end chips, posing a challenge to chipmakers in the long run (goover.ai summary)). Korean conglomerates are also venturing into AI services – e.g., LG’s AI research institute and Hyundai’s work on autonomous driving AI. And the government has created specialized institutions like an AI-focused bureau in Gyeonggi Province and even established with the WEF a Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution (C4IR) in Pangyo dedicated to startups and smart manufacturing (weforum.org).

However, even Korean officials acknowledge Korea “cannot keep up this momentum alone” in AI (intralinkgroup.com). Alexandra Gugay of Intralink Korea noted that opportunities abound for international AI firms in the Korean market, implying that Korea welcomes foreign collaboration to bolster its AI industry. This openness is a shift from the past when Korea’s innovation was more insular. It underlines that to maintain innovation leadership, Korea is looking to integrate into global innovation networks – attracting foreign AI talent, investors, and companies to participate in its ecosystem.

The Bet on the Future: In summary, South Korea’s current big bet is on becoming an “Innovation Nation” in the digital era, not just a manufacturing titan. It aims to harness AI, biotech, hydrogen economy, and other frontier technologies as new growth engines. The government has set ambitious goals (for instance, aiming to be one of the top 5 AI powers by 2030, establishing a “hydrogen economy” by 2025, etc.).

The challenge beyond 2025 will be executing these goals without falling victim to bureaucratic inertia or over-reliance on past models. South Korea will need to be agile, globally connected, and supportive of risk-taking, or else it could see its hard-won innovation lead erode as others surge ahead.

Nowhere is this challenge more evident than in the domain of startup financing, which we turn to next. As we’ll see, South Korea’s startups face a funding gap that could jeopardize their growth – a gap the country is attempting to fill through creative means like IP financing and other measures.

4. The Funding Gap: Why Korean Startups Still Struggle for Capital

Despite the surge in venture activity in recent years, many Korean startups still find it difficult to secure the funding needed to scale and compete globally. In fact, there are growing concerns of a funding crunch that could stall the momentum of Korea’s startup ecosystem. Several factors contribute to this funding gap:

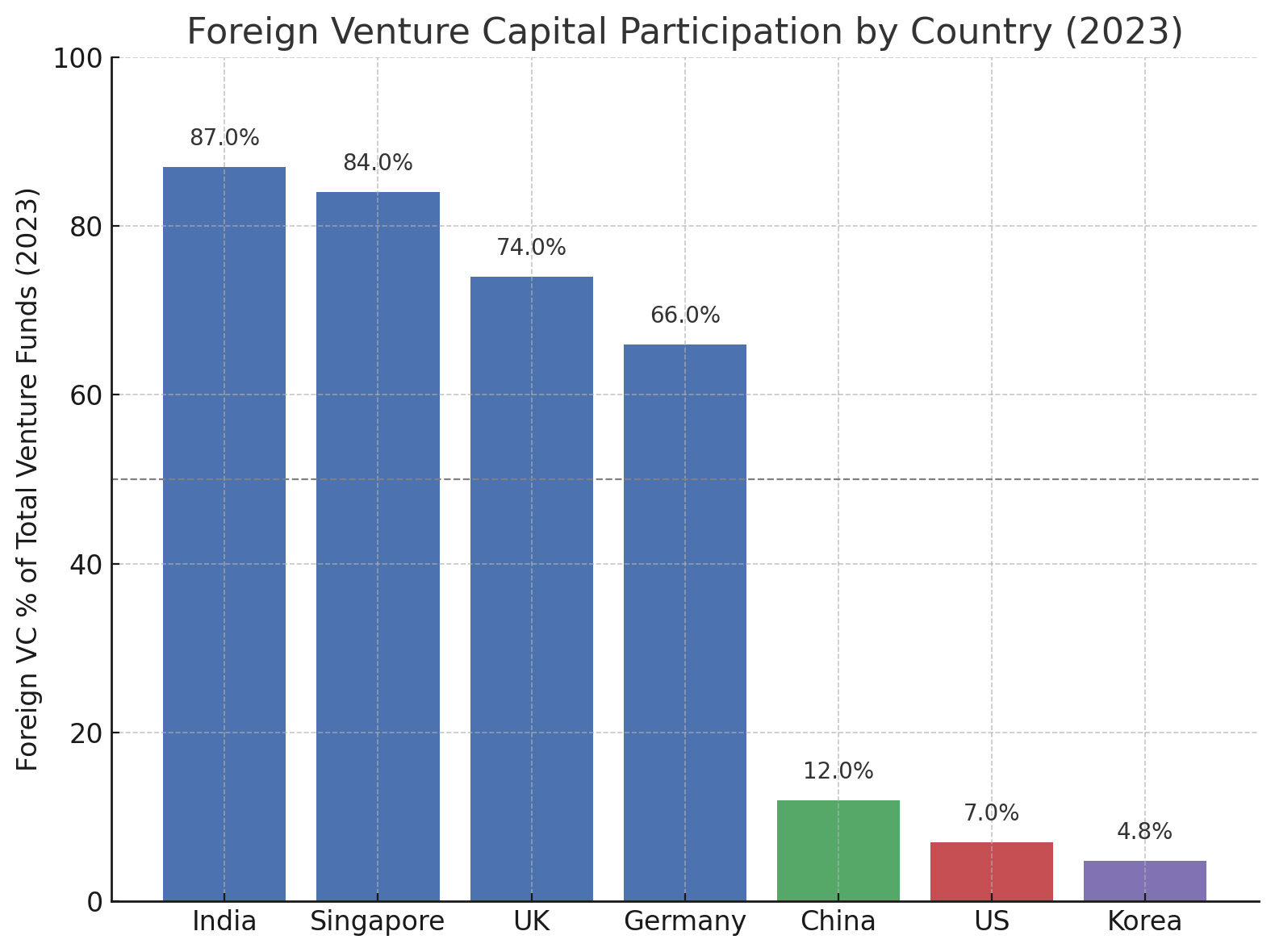

- Reliance on Domestic Capital: A striking difference between South Korea and some other startup hubs is the relatively small role of foreign venture capital in its ecosystem. Global investors have a limited presence in Korean startups, especially compared to other countries. In 2023, foreign VCs accounted for only 4.8% of total venture investment in Korea, down from an already low 6.6% in 2022 (php83.kode.co.kr). This is extremely low by global standards – for example, in 2023 87% of venture funds in India came from foreign capital, 84% in Singapore, 74% in the UK, 66% in Germany, even China had 12% foreign VC and the US 7%. The chart below highlights how Korea stands out at the low end for foreign VC participation:

Foreign share of venture capital funding by country (2023). South Korea’s startup funding relies overwhelmingly on domestic investors, unlike other markets that attract large foreign VC inflows (data source: KED Global/The VC).

This heavy reliance on domestic capital means that when local investors pull back, there aren’t enough foreign players to fill the gap. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened as global economic conditions tightened in 2022-2023 – Korean institutional investors became more cautious, and foreign investors did not pick up the slack.

- Venture Funding Cycles and the 2022-2023 Slump: After the record-breaking year in 2021 (₩7.7 trillion invested), 2022 saw a dip of around 12% in venture investment (to ~₩6.76 trillion) as global markets cooled (MSS data). The downturn intensified in 2023. In fact, funding into Korean tech startups plunged 61% in 2023, from $4.9B in 2022 to about $1.9B in 2023 (dealroom.co). By early 2024, observers noted startup funding was at a “7-year low” in Korea (php83.kode.co.kr). This sharp contraction, often dubbed a “startup funding winter,” left many companies scrambling for cash.

One outcome is that fewer new startups are being formed. The number of newly registered tech startups in Korea fell for a fourth straight year in 2024, down to ~214,917 (a 2.9% drop from 2023). While that figure includes all startups (not only VC-funded tech startups), it reflects a dampened enthusiasm due to funding challenges. Concerns are growing that the ecosystem could enter a vicious cycle of fewer startups, slower growth, and thus even less investment.

- Early-Stage Funding Crunch & Risk Aversion: Ironically, while overall venture funding fell, the share going to later-stage companies rose. In 2024, only 18.6% of VC investment went into startups aged 3 years or less, down from 26.9% in 2022. Meanwhile, over half of VC investment (53.3%) went to late-stage startups in 2024.

- This indicates that venture capitalists, facing a tighter market, have become more risk-averse – preferring to put money into more mature startups or follow-on rounds for proven companies, rather than seed or Series A rounds for new founders. “VCs in Korea are also too shy to invest in early-stage startups, even though they are meant to pursue high-risk investments for high rewards,” comments KED Global, pointing out the paradox that Korean VCs behave more like conservative banks (php83.kode.co.kr).

For a young founder with just an idea or prototype, this environment can be brutal. One local AI startup CEO recounted that it was “hard to raise funds from local VCs in the early stages without additional conditions – like being required to collaborate with a conglomerate – beyond just the startup’s growth potential”. And even when funding was secured, “the total funds I could raise in Korea was too little compared to the US, making me think relocating to the US is a better option,” he said (php83.kode.co.kr).

This illustrates how some Korean investors not only give less money, but also attach strings (perhaps to mitigate risk by involving a big partner), which can be stifling for a startup’s independence and growth.

- Lack of Exits (IPO/M&A) and Recycling of Capital: One major reason cited for investor hesitancy is the dearth of successful exits in Korea’s startup scene. In Silicon Valley, a virtuous cycle exists where investors fund startups, some startups IPO or get acquired for large sums, and those returns flow back to limited partners or spawn new angel investors, which in turn fund the next generation. In Korea, this cycle is nascent. The domestic IPO market has been weak – very few Korean startups have had blockbuster IPOs (Coupang being an outlier, and it listed in New York).

- On the M&A side, while conglomerates have acquired some startups, the pace is slower and deal sizes smaller than, say, big tech acquisitions in the US. KED Global reported that mergers and acquisitions of South Korean startups halved in value in 2024 compared to the prior year, as major acquirers like Naver and Kakao scaled back their buying sprees amid economic uncertainty (php83.kode.co.kr). With the “exit window” narrowing, venture investors are naturally more cautious since it’s harder to realize gains.

Industry observers note that many Korean institutional investors haven’t seen a major success from startup investments yet, so they remain on the fence. Culturally and structurally, Korea’s big financial institutions (pension funds, insurance, etc.) have only recently started allocating to venture capital, and they tend to set high due-diligence bars.

The result of all this? Some of Korea’s best startups are looking overseas for growth capital. As the local funding climate cooled, an increasing number of Korean startups have relocated or domiciled abroad (e.g., Singapore or the US) to tap foreign VCs. In 2024, 186 Korean startups moved their headquarters to foreign countries – nearly six times the number that did so in 2014. Many still keep operations in Korea, but seek foreign incorporation or offices to access global investors and markets.

A prominent example is FuriosaAI, one of Korea’s leading AI chip design startups. After achieving technical accolades, Furiosa struggled to raise the large sums needed for expensive semiconductor R&D within Korea. In 2025 it was reported that FuriosaAI was in talks to sell a stake to Meta (Facebook’s parent company) because it failed to find sufficient local investment (php83.kode.co.kr). This kind of development rings alarm bells: if domestic capital markets won’t back even a top-tier AI startup at scale, Korea could lose ownership of strategic technologies or see its innovations go abroad.

Indeed, Korean officials have expressed concern that “the tech startup ecosystem…would be trapped in a vicious circle” unless bold measures are taken (php83.kode.co.kr). The situation as of 2025 is that Korea has plenty of entrepreneurial talent and ideas, but financing them through the growth stages is a bottleneck. Especially for deep-tech startups (AI, biotech, etc.) requiring substantial capital, the gap is acute.

In response, the government and related agencies are seeking alternative ways to fund innovation, beyond the traditional VC route. This is where IP financing comes into play, alongside expanded government funds and incentives for private investors. In the next section, we delve into IP finance – an innovative approach South Korea has pioneered to leverage intellectual property as collateral or investment assets – and evaluate how much it can alleviate the funding challenges outlined above.

5. IP Finance: Leveraging Intangible Assets to Bridge the Gap

One bright spot in South Korea’s innovation policy toolkit is its aggressive adoption of IP (Intellectual Property) finance. Simply put, IP finance refers to financial instruments (loans, investments, guarantees) that are based on the value of a company’s intellectual property – such as patents, trademarks, or copyrights – rather than traditional tangible collateral like real estate or equipment. This is particularly relevant for tech startups and SMEs, whose most valuable assets are often intangible (e.g., patents, proprietary technology, software, content) but who lack physical collateral or large revenues.

By monetizing IP, these companies can access capital that would otherwise be unavailable from banks or investors who shy away from asset-light businesses.

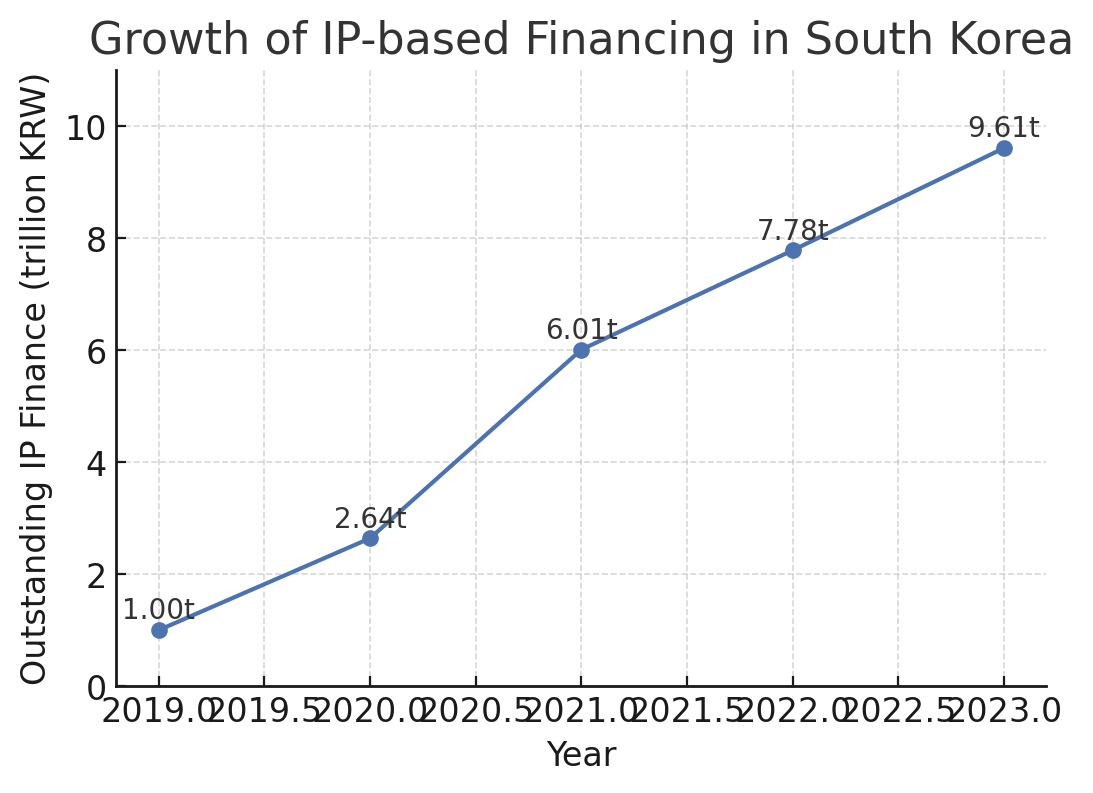

South Korea has emerged as a global leader in IP-backed financing, thanks to concerted efforts by government bodies like the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO) and financial institutions. The results have been impressive: the total IP finance market in South Korea has grown exponentially in recent years.

In 2019, the cumulative amount of IP-backed financing was around ₩1 trillion. By 2020, it had more than doubled to ₩2.64 trillion (kipo.go.kr). Then, backed by new policies, it surged to ₩6.01 trillion in 2021, ₩7.78 trillion in 2022, and nearly ₩9.61 trillion by the end of 2023 (kipo.go.kr). In other words, in just four years the outstanding amount of IP finance in Korea increased almost ten-fold – a remarkable growth trajectory. The chart below illustrates this rapid rise:

Growth of South Korea’s IP-based financing (outstanding amounts) from 2019 to 2023 (in trillion KRW). Starting around ₩1 trillion in 2019, IP finance has expanded to over ₩9.6 trillion by 2023, reflecting an annual growth rate exceeding 25% (data source: KIPO press release).

Breaking down the components of IP finance in Korea (as of 2023): roughly ₩2.32 trillion are loans collateralized by IP assets, ₩4.09 trillion are IP guarantees (more on that in a moment), and ₩3.19 trillion are IP-based investments (equity investments into companies with strong IP or direct purchase of IP rights). Each of these plays a role:

- IP-Backed Loans: Banks provide loans to a company, accepting the company’s patents or other IP as collateral. If the company defaults, the bank has claim to the IP assets (which ideally have been valued by professional appraisers). Traditionally, banks wouldn’t lend to a loss-making startup with no collateral; but with government encouragement, Korean banks have opened their coffers for IP-rich firms. By 2020, private banks made up nearly 70% of IP collateral loans (led by Industrial Bank of Korea, Woori Bank, Shinhan Bank) as they expanded services for “patent-rich companies” (kipo.go.kr).

- The government often supports such lending by subsidizing interest rates (KIPO offered special low interest programs ~2% for IP loans, versus typical SME loan rates of 3-4%). Crucially, IP-backed loans have reached companies that otherwise had low credit ratings – 74% of firms receiving IP collateral loans in 2020 had sub-investment grade credit (BB or below). This demonstrates IP finance’s power to extend credit to riskier, young ventures that banks would normally reject.

- IP Guarantees: Here, public institutions like the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund (KODIT) or Korea Technology Finance Corporation (KOTEC, also known as KIBO) evaluate a firm’s IP and issue a guarantee to banks, essentially co-signing the loan. If the company defaults, the guarantee fund covers the bank’s losses (and then recoups by possibly taking over the IP). This mechanism further encourages banks to lend by reducing their risk. Korea’s **“IP guarantee” programs have grown as well – ₩0.99 trillion of new IP guarantees were provided in 2023 alone, up 13% from 2022 (kipo.go.kr).

- These guarantees are especially helpful for early-stage startups that may not even have multiple patents to collateralize yet; even one promising patent can be used to get a guarantee and loan of, say, a few hundred million KRW. In a 2024 case, a small telecom equipment startup used 1 patent to get an IP guarantee, which allowed them to secure a ₩300 million bank loan for working capital – critical for buying raw materials and continuing operations (kipo.go.kr). For a hardware startup with long inventory cycles, this can be a lifesaver.

- IP Investments: This refers to equity or quasi-equity investments tied to IP. One form is when venture capital or specialized funds invest in a company specifically because it has valuable IP, sometimes even valuing the company’s IP separately. Another form is a direct purchase of IP (patents) by funds who then license them back to the company (this can be a way to raise cash without incurring debt). Korea has fostered IP-specialized investment funds, often seeded by government fund-of-funds money. By 2023, new IP-based investments in that year were **₩1.3365 trillion, continuing an increasing trend (up 3.1% from the previous year which was the first time above ₩1 trillion). The government’s role is notable – via agencies like KVIC (Korea Venture Investment Corp) and KIPO, it has channeled capital to IP funds. These funds co-invest with private VCs, focusing on IP-heavy sectors. The government’s hope is that IP investment becomes an “important priming water (마중물) for corporate growth,” bridging startups to their next stage (kipo.go.kr).

Real-World Impact – Case Studies: The statistics are impressive, but what do they mean on the ground? Let’s look at a few examples of IP finance enabling innovation:

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, a Korean biotech SME was developing a vaccine but had maxed out its credit lines. Traditional loans were not an option. However, the firm owned promising patents on “genetic scissors” (likely CRISPR-related) technology. In 2020, they were able to use 7 of their patents as collateral to secure a ₩2 billion loan, which financed clinical trials and continued R&D. This IP-backed loan quite literally kept their vaccine project alive. (This case is reminiscent of how in other countries, biotech startups often rely on IP assets – but Korea provided a structured way to fund them through bank loans rather than just equity).

- In 2013 (early days of Korea’s IP finance push), a small materials company with a crucial patent for LED/semiconductor materials received a ₩1.6 billion investment from a patent-specialized fund, recognizing the value of its technology (kipo.go.kr). With that capital, the SME scaled up and successfully localized production of materials that previously had to be imported. By 2020, that company had become the world’s #1 supplier of a particular solar cell material (TMA). This illustrates the long-term impact: IP finance can identify hidden champions and give them the boost to become global leaders in niche technologies.

- In 2023, a Korean startup developing next-generation AI chips (NPU – neural processing units) needed funding to hire top talent and speed up R&D. The company, being in deep tech, had strong IP – patents related to large language model (LLM) optimization and generative AI hardware. A private investment firm evaluated the startup’s patents and technical capability, judged it to be exceptional, and provided an ₩2.6 billion investment in exchange for equity, justified by the IP value (kipo.go.kr). The infusion came at a critical time and helped the startup gain recognition; soon after, the company won an Innovation Award at CES 2024 for its AI chip (kipo.go.kr). This story (drawn from a KIPO press release) demonstrates how IP valuation can validate a startup’s work and attract investors who might otherwise hesitate at a pre-revenue chip company. Essentially, the patents acted as a signal of quality and a form of collateral for equity investment, not just loans. It’s also a prime example of IP finance directly benefiting an AI company – showing that IP finance isn’t only for biotech or traditional tech, but is being used to support cutting-edge AI innovation in Korea.

- Another case: A small electronics firm specializing in online advertising platforms struggled to get working capital because it had little revenue initially. Through KIBO’s fast IP evaluation system, it obtained an IP guarantee in about one week, which enabled a bank loan that kept the business operational (kipo.go.kr). The speed here is key – Korea invested in systems like SMART3 and KPAS II for real-time patent grading. This addresses a common bottleneck: evaluating IP used to take months and a lot of expert work; Korea’s semi-automated tools cut it down significantly, meeting startups’ need for quick financing.

These examples underscore that IP finance is indeed helping to fill some financing gaps. It particularly aids companies that are rich in innovation but poor in assets or cash – a profile that fits many startups and SMEs. By 2023, IP finance had provided funding to thousands of companies; in 2020 alone, over 1,600 companies received IP-backed loans (kipo.go.kr). Importantly, over 80% of the beneficiaries are lower-credit firms that likely would have been denied credit under normal circumstances. This suggests IP finance has improved financial inclusion for innovative enterprises.

6. Can IP Finance Solve the Funding Gap? A Critical Assessment

Given the success stories above, one might wonder: could IP finance be the silver bullet that solves South Korea’s startup funding gap? The evidence shows it’s a powerful tool – South Korea has essentially unlocked a new source of capital totaling nearly ₩10 trillion that didn’t exist a few years ago, specifically directed at innovation. However, it’s not a panacea. Let’s critically examine the strengths and limitations of IP finance in addressing the funding challenges we outlined.

Benefits and Strengths of IP Finance:

- Unlocking Bank Financing for Startups: Perhaps the biggest impact of IP finance is that it brings banks and traditional finance into the startup funding arena, which historically was almost exclusively the domain of equity investors (VCs, angels). Korean banks, thanks to IP collateral and guarantees, are now lending to startups and tech SMEs in volumes never seen before. This diversifies the funding sources for startups. Instead of relying only on VC (which, as we saw, can retreat in tough times), a startup can get a loan or credit line to weather short-term needs or finance R&D. Importantly, these loans often come with **low interest (sometimes subsidized around 2-3%), easing the cost of capital for the company. For example, during COVID-19, IP-backed loans helped SMEs survive when revenues were hit (kipo.go.kr). This shows resilience: even if equity investors pull back, debt via IP can sustain companies.

- Bridging the “Valley of Death”: In innovation policy, the “valley of death” refers to the phase where a project is too commercial for research grants but too risky for private investors – often the prototype or product development stage. IP finance (especially IP-specific investment funds and guarantees) has provided capital in this gap. The patent fund investment into the LED materials company is a classic case of bridging the valley of death – taking a lab innovation to commercial production (kipo.go.kr). By valuing the underlying IP, these mechanisms can justify funding projects that haven’t generated revenue yet but hold promise. This is crucial for deep tech, where development cycles are long.

- Encouraging a Culture of IP and Innovation: The rise of IP finance creates positive incentives for companies to create and protect intellectual property. Knowing that patents can literally be turned into money, entrepreneurs have more motivation to file patents, build patent portfolios, and by extension, focus on genuine technological innovation rather than just short-term gains. It’s telling that Korea is among the world’s top 5 patent-filing countries (intralinkgroup.com). While they were already prolific filers, IP finance adds an extra reason: a patent could secure your next round of funding. This also pushes the ecosystem to improve IP valuation skills, patent analytics, and legal frameworks. In fact, Korea’s advances in **real-time IP evaluation systems (SMART3, KPAS II) are quite innovative in their own right, potentially models for other countries.

- Mitigating Investor Risk and Attracting Capital: By providing guarantees or collateralization, IP finance reduces the risk for lenders and investors. This can crowd-in private capital. For instance, once a startup has an IP guarantee for a portion of a loan, a bank might be willing to lend more on top. Or if a patent fund invests in a startup, it can give confidence to other VCs that the company’s tech is solid (since it passed an IP due diligence). In essence, IP finance can act as a signal of quality and a form of credit enhancement. The government’s active role via KIPO and others also signals to the market that these startups are backed by state support, indirectly encouraging investors.

- Success Stories Breed Confidence: As more examples of successful IP-financed companies emerge (like the material supplier turned global leader, or the AI chip startup making headlines), it builds confidence in the approach. That could lead to scale-ups of IP funds, more banks participating, and perhaps even securitization of IP loans (where loan portfolios could be packaged and sold to investors, further freeing bank capital). KIPO’s 2024 statement noted that “we have entered a growth phase of IP financing, and now it’s important to induce natural growth in the financial market”, implying the aim is to make this self-sustaining with private sector taking the leadkipo.go.kr. The government pledged to continue supporting high-quality IP valuation services to facilitate this (kipo.go.kr).

Limitations and Challenges:

For all its merits, IP finance is not a cure-all, and there are challenges and limitations to acknowledge:

- Not All Startups Have Strong IP: IP finance disproportionately benefits startups in sectors where patents and formal IP are crucial – e.g., biotech, semiconductors, chemicals, some AI algorithms, etc. However, many startups, especially in the digital realm (think social apps, gaming, marketplace platforms, software without novel algorithms), do not have significant patentable IP. Their value lies in user growth, network effects, brand, or trade secrets. These companies might not be able to leverage IP finance beyond perhaps trademark collateral or so (which is much harder to value). For example, a fintech app or an e-commerce platform may have zero patents; thus IP finance tools would pass them by. The Korean startup ecosystem has a large chunk of such companies. For them, traditional venture investment is still needed, and the funding gap remains if VCs are shy.

- Valuation Difficulties and Risk for Lenders: Accurately valuing IP is a complex task. While Korea’s SMART3 and other systems provide automated scoring, there is always a degree of uncertainty in what a patent is truly worth. Patents do not always translate to commercial success – one patent might be extremely valuable if it’s essential to a standard or product, while a hundred others might be virtually useless if the market doesn’t adopt that tech. If banks end up with foreclosed patents, monetizing those patents is non-trivial (they’d need to auction them or license them out, which is not a core competency of banks). So far, default rates on IP loans haven’t been widely reported, possibly because many are guaranteed or interest-subsidized. But as the volume grows, there is a question of how sustainable it is without government backing. In short, there is still risk being carried by public institutions (KODIT, KIBO) that absorb losses if a startup fails. If too many bets go bad, it could strain those institutions or taxpayers. This hasn’t happened yet – but mostly because the program is relatively new and the government has been willing to absorb costs for the sake of policy. Over the long term, a market-driven pricing of IP loan risk needs to develop.

- Scale and Ticket Size: While ₩10 trillion is a large number, recall that annual venture investments were around ₩7-8 trillion at peak. IP finance is supplementary but not completely replacing venture capital. Also, IP loans or investments for a single company might be on the order of ₩1-10 billion typically (with some bigger outliers). A startup aiming to become a unicorn often needs tens of millions of dollars (hundreds of billions of KRW). It’s unlikely they can get, say, a ₩100 billion pure IP-backed loan – the exposure would be too high for one bank on one risky venture. Mega-deals still require large equity infusions or corporate partnerships. For example, FuriosaAI reportedly sought hundreds of billions of KRW for its next phase – something only a big corporate like Meta or a state-backed fund could provide, not a standard IP loan (hence the approach to Meta). So, IP finance fills gaps mostly in the early to mid-stage financing (seed to Series B/C, and working capital for SMEs). For very large scale-ups, Korea still needs more late-stage capital and perhaps strategic investors.

- Dependency on Government and Policy: So far, the rapid expansion of IP finance in Korea has been highly policy-driven. Interest subsidies, government-founded IP funds, evaluation systems built by KIPO, etc., are the scaffolding. A critical view might ask: is this simply a form of indirect state aid to startups (not that that’s bad)? And will private players continue to participate if, say, interest rates rise or subsidies are removed? In 2023, for instance, high interest rates actually led to a slight dip in new IP collateral loans (down a bit from 2022’s level) because the cost of borrowing rose and some firms hesitated (kipo.go.kr). This suggests that macroeconomic factors still influence IP finance uptake. Additionally, if the government changes priorities or if there’s a perception of abuse (e.g., firms getting loans on shaky IP and defaulting intentionally), there could be political blowback. Maintaining rigorous IP valuation standards and transparency is key to long-term credibility.

- Awareness and Education: Many entrepreneurs and even bankers initially had low awareness about IP finance opportunities. This is improving, but there’s a learning curve. The process of getting an IP valuation, dealing with KIPO or guarantee funds, can be bureaucratic. For time-strapped founders, it might seem daunting. Korea has been conducting outreach – for example, holding IP finance fairs and consulting – to educate the industry (msit.go.kr press releases mention IP-Finance networking events). Over time, one would hope IP finance becomes as straightforward as applying for any business loan. Streamlining the process (perhaps more online platforms) will be important to scale it further.

The Bigger Picture – Complementary Reforms: IP finance alone cannot solve all funding issues; it should be viewed as one pillar in a multipronged strategy. Other necessary measures include:

- Improving exit opportunities: Encourage more acquisitions and IPOs. The government in late 2022 and 2023 rolled out measures to ease listing rules on Korea’s KOSDAQ (tech-heavy stock market) and incentivize corporate M&A of startups (tax breaks, etc.). For instance, allowing dual-class shares could enable founder-led startups to go public without losing control, making IPOs more attractive. If exits improve, venture capital will become more abundant, filling the gap from the equity side.

- Attracting Foreign Venture Capital: Korea could further open its market to foreign investors – e.g., by marketing Korean startups abroad, creating English-language investment platforms, and perhaps co-investment programs where foreign VCs get matching funds from Korean funders. The stark contrast with India or Singapore in foreign VC percentage (refer to the chart above) suggests a lot of untapped potential. Recent data shows global VC market revived in 2023-24 with the AI boom, but the Korean VC market remained lackluster (php83.kode.co.kr). Bridging that disconnect is crucial. On a positive note, Q1 2025 saw a rebound in Korea’s venture investment (₩2.62 trillion, up 34% YoY), and notably, **private sector contributions led the formation of new venture funds (₩2.6 trillion from private sources in Q1 2025, +31% YoY). This indicates domestic investors are slowly coming back, and if foreign ones join, the pie could grow further.

- Regulatory Reform and Supportive Policy: Aligning with the ITIF recommendation, Korea is actively discussing moving from “positive” to “negative” regulatory regimes in sectors like fintech, biotech and AI – essentially adopting sandbox programs and more flexible rules so that startups can operate new business models without months of approval delays (itif.org). The Yoon administration (2022–27) prioritized regulatory sandbox expansions and even designated special “regulation-free” zones in areas like AI/data in Busan and elsewhere. Reducing regulatory friction lowers costs for startups, indirectly making the funding they do have stretch further. It also encourages more startups to be founded (which in turn draws more investment).

- Cultural and Educational Factors: Continuing to celebrate entrepreneurship and tolerating failure will help ensure a steady pipeline of innovators. Korea’s culture has traditionally stigmatized business failure, but that’s slowly changing as high-profile founders share stories and universities set up entrepreneurship programs. The more people try, the higher the chance of big successes that attract funding.

In conclusion, IP finance is a highly promising piece of the puzzle. It has demonstrably filled a gap, particularly for SMEs with valuable technology but insufficient collateral or credit. South Korea’s pioneering efforts in this area are being watched by other countries – for instance, Hong Kong has shown interest in Korea’s IP finance model (fsdc.org.hk), and organizations like WIPO have lauded Korea’s approach (WIPO even held an “IP Finance Dialogue” noting Korea’s success in securing $2.2B worth of IP-backed loans and the role of debt funds to fill the gap). This suggests Korea is onto something that could be exported as best practice.

That said, IP finance should not be viewed in isolation. It works best in tandem with a vibrant venture capital market, forward-looking regulations, and a culture that embraces innovation. If venture funding is the equity engine and IP finance the debt engine, Korea will want both running smoothly to propel its startups. IP finance can alleviate some pressure (especially for working capital and mid-stage growth), but startups aiming for global scale will still seek large equity rounds that only a robust VC ecosystem (domestic and foreign) can provide.

7. Conclusion: Ensuring the Bet Pays Off

South Korea stands at a pivotal moment. The bet it placed in the late 20th century on heavy industries and conglomerates transformed it into a developed nation and tech leader – a bet that has paid off in making Korea an innovation powerhouse in fields like semiconductors, consumer electronics, and automotive engineering. Now, the challenge of 2025 and beyond is to ensure that this bet hasn’t come at the cost of future innovation leadership. This means Korea must adapt and extend its model to foster new kinds of innovation that the chaebol-driven era did not prioritize.

From our analysis, several key insights emerge:

- Balance Conglomerates and Startups: Korea has recognized the need to strike a balance between its mighty conglomerates and the nimble startups that could be tomorrow’s giants. Significant strides have been made with the rise of startups, increased venture funding (at least until the recent dip), and cultural shifts favoring entrepreneurship. Government initiatives like the Ministry of Startups, TIPS, and regulatory sandboxes have been instrumental. The startup sector’s growth, in terms of investment and job creation, shows that the innovation ecosystem in Korea is broadening beyond the old guardweforum.org. The crucial next step is to institutionalize this progress, making it resilient to political changes or economic cycles.

- That means permanent channels for dialogue and partnership between startups and large firms (so innovation flows in both directions), and sustained support for startups even when economic winds are less favorable.

- Stay Ahead in the Technology Race: In emerging tech domains (AI, biotech, green tech, etc.), Korea cannot rest on its laurels. Competitors like the U.S. and China are racing full steam ahead. Korea brings significant strengths – a highly educated workforce, strong R&D spending, advanced infrastructure (e.g., among the world’s best broadband and 5G networks), and companies like Samsung that excel in hardware. However, weaknesses such as rigid regulations, relatively small domestic market, and a shortage of certain talent (e.g., top AI researchers) need to be addressed.

- Efforts like regulatory reform, international collaboration (e.g., inviting global AI firms to Pangyo as mentioned by Alexandra Gugayintralinkgroup.com), and nurturing STEM talent (possibly through immigration or overseas training programs) will be key. South Korea’s future innovation leadership hinges on being a leader not just in refining existing technologies, but in pioneering new ones. That may require a mindset shift towards accepting uncertainty and failure, which are inherent in cutting-edge innovation.

- Bridge the Funding Gap – Multiple Tools Needed: The funding challenges for Korean startups are real, but not insurmountable. IP finance has emerged as a powerful tool in Korea’s arsenal, and it provides a model for how to support intangible-intensive businesses. It has enabled many innovative companies to survive and grow when traditional financing might have turned them away. By continuing to expand and refine IP finance (and sharing the risk intelligently between public and private sectors), Korea can mitigate one part of the funding gap. But other parts of the gap must be tackled through revitalizing venture capital investment and attracting global capital.

- The data clearly shows that Korea lags in foreign VC participation (php83.kode.co.kr), which is both a challenge and an opportunity – if Korea can improve its startup investment climate, there is a large pool of international capital that could flow in. Measures might include easing foreign investor regulations, protecting minority shareholder rights in startups, and marketing success stories abroad to pique interest.

- Encourage Exits and Recycling of Success: A critical piece of the puzzle is to have more success stories – the Korean versions of Google, BioNTech, or Tesla, for instance. Success breeds success: when a Korean startup has a massive IPO or acquisition, it not only validates the ecosystem but also creates wealth that often gets reinvested (founders become angel investors, employees spin off their own startups, venture funds see returns and raise larger follow-on funds). Korea’s government and financial community should therefore focus on building a better pipeline for IPOs and facilitating M&A. The recent policies to ease listing requirements on KOSDAQ and promote “Open Innovation” M&As by chaebols are steps in the right direction. If even a fraction of the billions sitting in Korean pension funds or chaebol cash reserves are funneled into acquiring or scaling startups, it could dramatically boost the ecosystem.

(There are signs of change: for example, Hyundai acquiring an 80% stake in Boston Dynamics (a U.S. robotics startup) or Naver acquiring Wattpad (an online writing platform) show Korean corporates’ increasing appetite for tech acquisitions, which could eventually include more domestic startups as well.)

- Leverage Strength in IP Globally: South Korea can also leverage its IP prowess internationally. With such strong patent portfolios, Korean companies (big and small) could monetize IP overseas through licensing deals, patent pools, or cross-border IP-backed lending. Already, Korean firms are among the top filers in the U.S. and Europe. The government’s push for IP finance could be exported: helping other countries set up similar frameworks could open new markets for Korean IP valuation services, and also ensure Korean companies’ IP is recognized as collateral abroad. In the long run, perhaps Korean startups could even raise IP-backed loans from foreign banks if those banks trust the valuation – a scenario that would truly globalize the concept of IP finance.

In reflecting on the central question – has Korea’s past bet jeopardized its future innovation? – the evidence suggests that Korea is actively course-correcting to avoid that fate. Yes, the dominance of chaebols and the focus on manufacturing created some inertia and structural issues, but Korea is not complacent. Policymakers and industry leaders clearly acknowledge the risks (whether it’s reading think-tank reports about regulatory drag (itif.org) or observing that startup dynamism needs to improve). The very fact that Korea leads in experimenting with things like IP finance shows an innovative approach to policymaking itself. Few countries have tried so deliberately to convert intangibles into financial capital at this scale – Korea did, because it saw the need to support innovation through new means.

The road ahead will require perseverance. Global economic conditions (interest rates, geopolitical tensions) can affect Korea’s innovation trajectory in unpredictable ways. Domestically, political shifts could alter priorities (for instance, the opposition Democratic Party in early 2024 won a supermajority in the legislature, which might lead to different emphases – the Carnegie paper noted potential differences such as the opposition favoring higher taxes or more regulation in certain areas). Regardless of politics, however, supporting innovation has broad consensus in Korea – it’s seen as essential for the nation’s future, especially given challenges like a rapidly aging population and slowing growth that make productivity and innovation even more critical.

In conclusion, South Korea can indeed secure its future innovation leadership if it continues to adapt and innovate in its support structures as much as in technology itself. The country’s bet on manufacturing and conglomerates has given it a formidable platform – world-class companies, infrastructure, and human capital. Now a new bet is being placed: on startups, on AI and digital transformation, and on creative financial solutions like IP-backed funding. If executed well, this bet does not replace the old one but builds on it, ensuring that the successes of the past become the foundation for the successes of the future, not a ceiling that limits them.

South Korea’s story from 2025 onward could very well be one of a nation that reinvented its innovation model and continued to thrive – a story of an ever-evolving innovation powerhouse that meets the challenges of each era with ingenuity and determination. With the evidence of recent trends and the initiatives underway, there is strong reason to be optimistic that Korea’s best days of innovation are still ahead, not behind.

Member discussion