Syndication in Biopharma Royalty Financings: Why $900 Million Deals Still Don't Have a Syndicate

When Agios Pharmaceuticals sold its vorasidenib royalty to Royalty Pharma for $905m in 2024, a single buyer wrote the entire cheque. There were no co-investors, no club structure and no syndicate desk. In leveraged finance, a transaction of that scale would almost certainly require multiple lenders. In biopharma royalty financing, it did not.

That fact, repeated across dozens of publicly disclosed transactions between 2024 and early 2026, says something important about how pharmaceutical royalty markets work, why they resist the syndication dynamics common in other capital markets and what it would take for that to change.

This analysis draws on SEC filings, issuer press releases and legal surveys to examine when, why and how biopharma royalty financings involve multiple buyers, and why the answer, in most cases, is that they do not.

The disclosure record: single buyers dominate

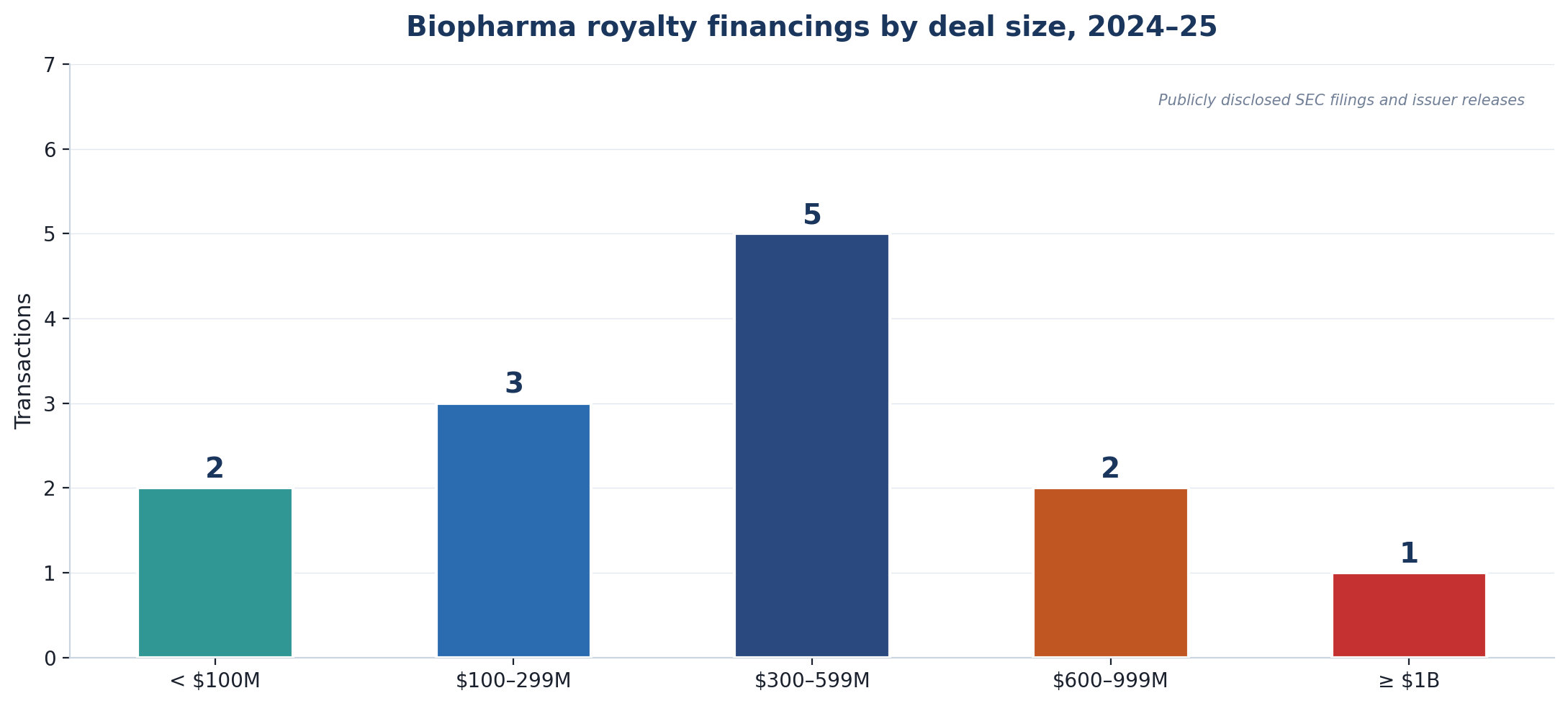

Legal surveys of publicly reported royalty transactions, notably Gibson Dunn's Royalty Finance Report covering 2020-2024 and the firm's H1 2025 update, confirm that these transactions are purpose-built, with heavy negotiated terms around milestones, liens and control packages. Gibson Dunn's H1 2025 data showed aggregate volume annualising at $5.42bn (versus $5.07bn for 2024), with the average transaction at $225.94m and average upfront payment at $114.92m, the latter declining steadily for three consecutive years. This bespoke orientation works against broad primary-market syndication, which depends on standardisation and repeatable documentation.

Two visible 2024 transactions illustrate single-platform underwriting at scale:

Agios to Royalty Pharma ($905m). Agios received $905m upon FDA approval in exchange for a tiered royalty on US net sales: 15% up to $1bn in annual net sales, 12% above that threshold, with Agios retaining 3% above $1bn. One buyer. No syndicate.

Esperion to OMERS ($305m). Esperion's agreement with OMERS' OCM IP Healthcare Portfolio LP set a $304.656m purchase price for 100% of specified receivables until a cap of $517.915m was reached, effectively embedding a return cap via a cashflow cap.

Even at the upper end of the market, a single platform commonly takes the full position.

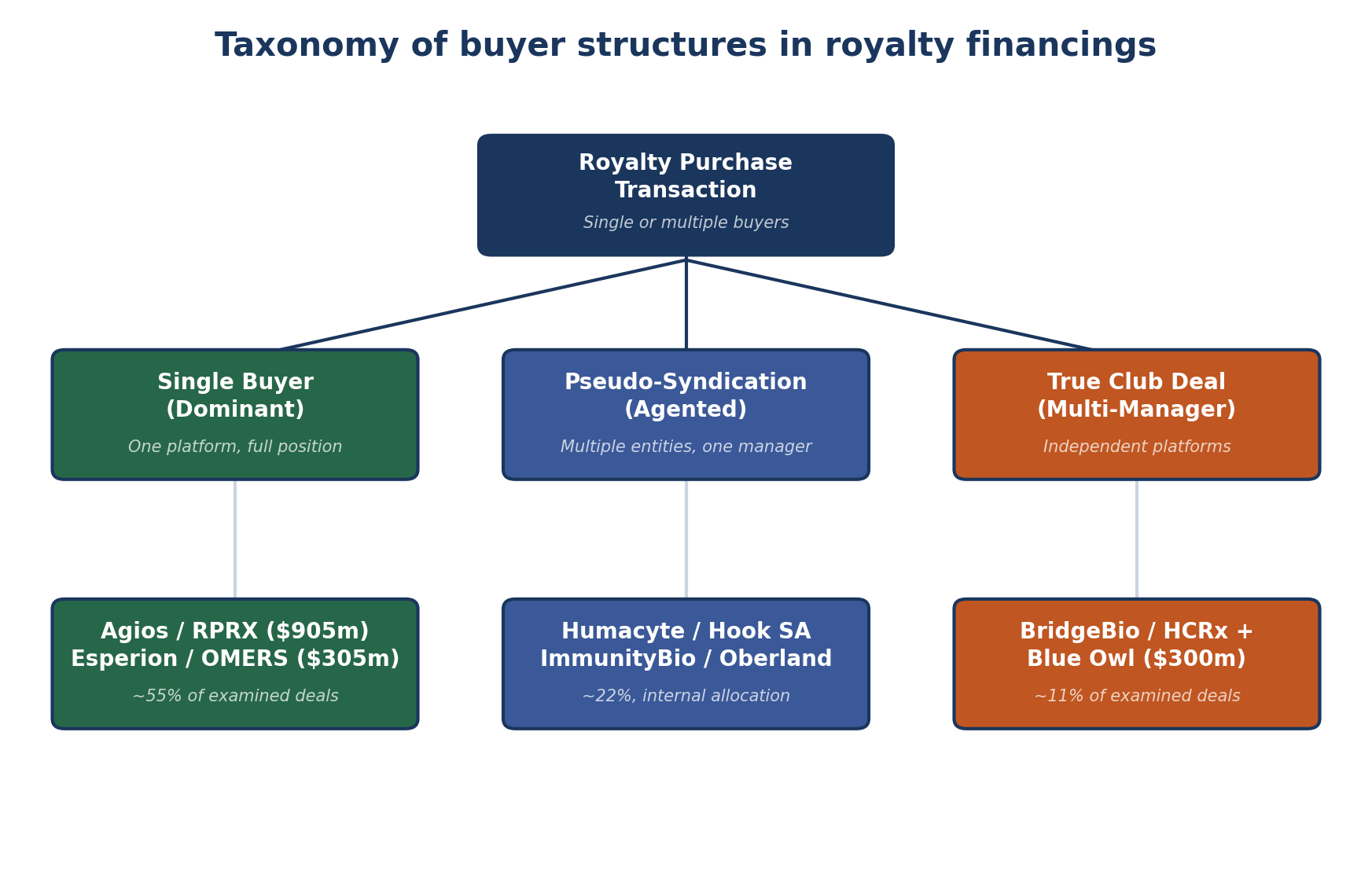

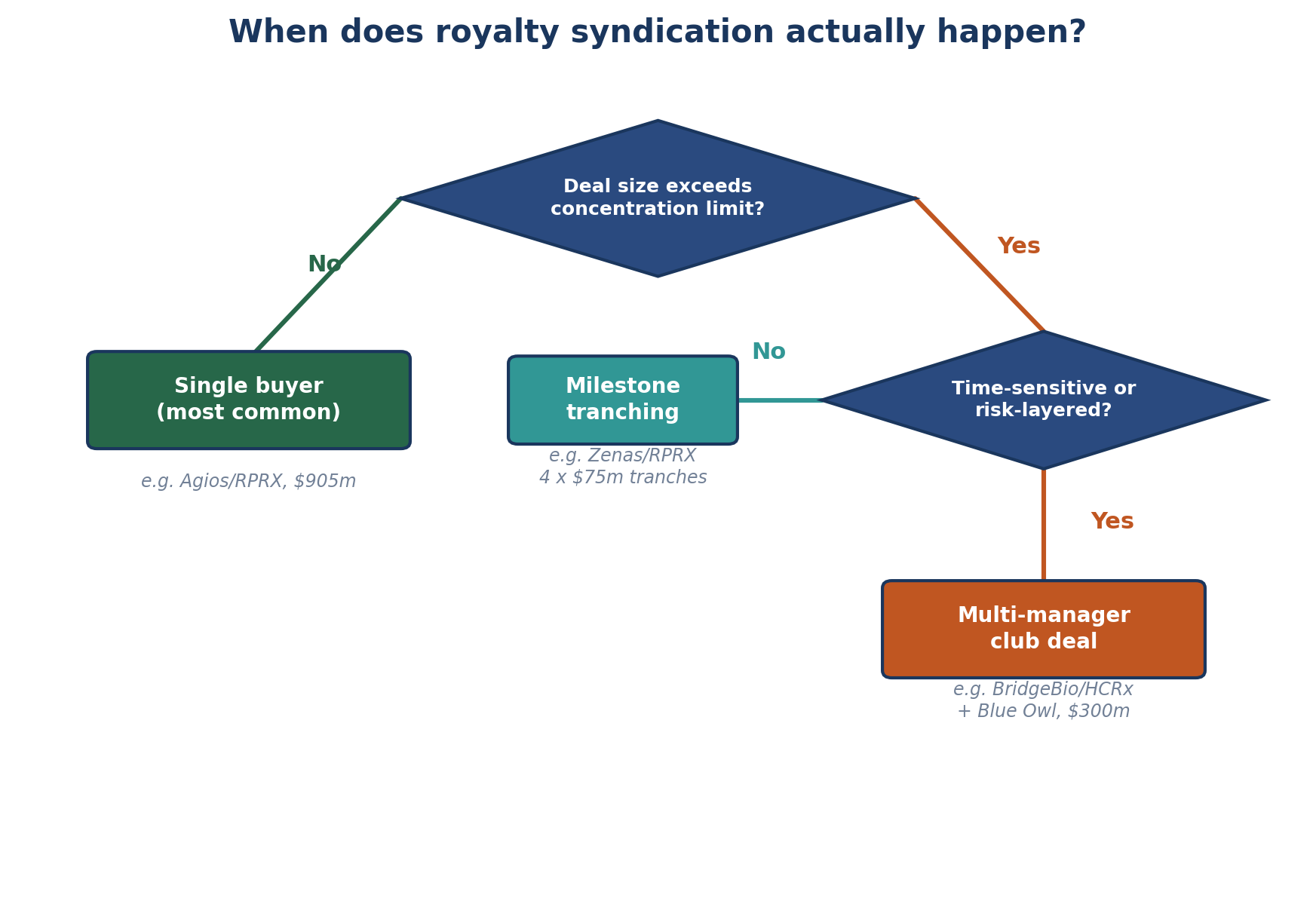

When club deals happen

True multi-manager syndication does occur, but it appears to be the exception in the disclosure record. Across the representative 2024-2026 transaction set examined here, only one deal (BridgeBio) involves genuinely independent platforms sharing a single royalty position. One further deal (Geron) involves two providers offering complementary instruments. The remainder are single-buyer transactions or multi-entity structures within a single platform.

BridgeBio to HCRx and Blue Owl ($300m)

The clearest 2025 example: BridgeBio sold a portion of BEYONTTRA European royalties to HealthCare Royalty and funds managed by Blue Owl Capital for $300m (net proceeds approximately $297m). The structure monetised 60% of BridgeBio's European royalties on the first $500m of annual BEYONTTRA net sales, with total payments to the investors subject to an initial cap of 1.45x.

This deal shows joint underwriting across genuinely different platforms, a royalty purchase and sale form that can accommodate shared economics, and a willingness to syndicate at the roughly $300m scale. It is worth noting that HCRx and Blue Owl have a repeat co-investment relationship. They jointly provided a $250m term loan to TG Therapeutics in 2024, splitting $125m each. Established bilateral partnerships appear to reduce the coordination costs that otherwise inhibit multi-manager deals.

Geron to Royalty Pharma and Pharmakon ($375m)

Geron's November 2024 financing is a hybrid model: up to $375m total, with $250m provided at closing. The package comprises a synthetic royalty from Royalty Pharma (with payout ceasing after a return multiple) and a five-year senior secured loan with a tranche draw structure from Pharmakon Advisors. Two parties provided complementary instruments rather than splitting a single royalty position.

Pseudo-syndication: multiple entities, single platform

A separate pattern deserves careful distinction: transactions that appear multi-party in the signature blocks but are economically controlled by a single manager.

Humacyte's RIPA names multiple purchasers, TPC Investments III LP and TPC Investments Solutions LP, with Hook SA LLC as Purchaser Agent and pro-rata purchasing language. Aggregate consideration runs up to $150m per the amendment recital. The documentation supports multiple holders with Purchaser Agent governance, Required Purchasers consent and pro-rata portions. But this is better understood as internal allocation across vehicles within one platform. The revenue-interest obligations are explicitly framed as debt, with debtor-creditor intent stated in the contract.

ImmunityBio's royalty financing follows a similar pattern: a $200m first payment and $100m additional purchase after FDA approval (up to $300m in royalty financing plus equity), structured through Oberland Capital via Infinity SA LLC as Purchaser Agent. The purchasers are not individually named in the 8-K summary and are described as affiliates via the agent framing.

Castle Creek/Ligand represents a more ambiguous case. The purchase agreement names Ligand as Purchaser Representative with multiple purchasers on Schedule I (not reproduced in the public exhibit), allocation percentages per purchaser and "Required Purchasers" consent for amendments. Prices and allocations are partially redacted. Whether the purchasers listed on Schedule I are affiliated or independent platforms cannot be determined from the public filing. The governance mechanics, however, illustrate how syndication documentation works in practice.

Syndication by the numbers

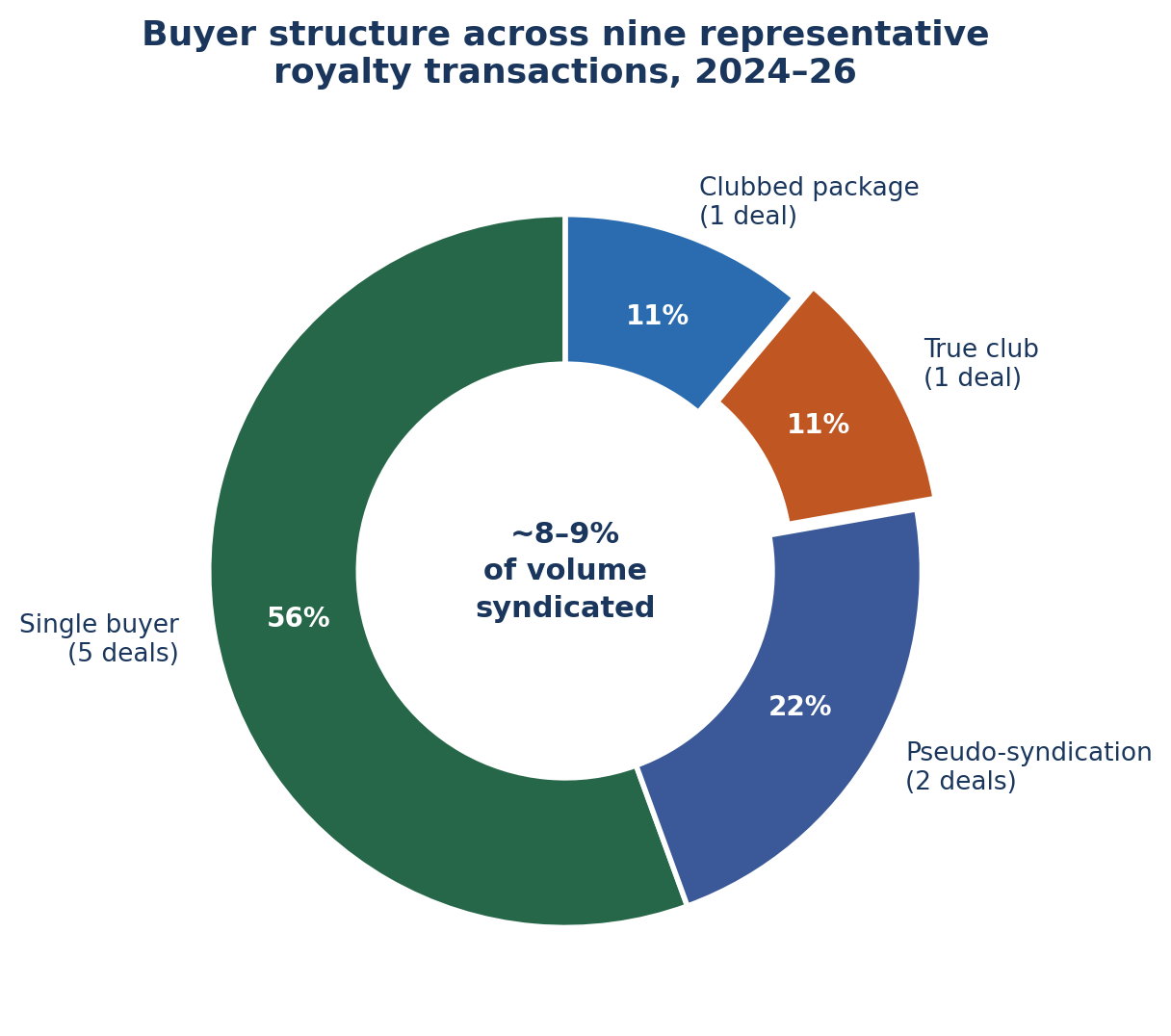

Across the nine representative transactions examined:

- 5 of 9 are single-buyer transactions with no disclosed syndicate members (Agios, Esperion, scPharmaceuticals, Zenas and, effectively, Castle Creek where the purchaser list is redacted)

- 2 of 9 involve agented multi-purchaser structures that probably represent single-platform economics across affiliated vehicles (ImmunityBio/Oberland, Humacyte/Hook SA)

- 1 of 9 is a genuine two-manager club deal (BridgeBio to HCRx and Blue Owl)

- 1 of 9 is a clubbed multi-provider package with complementary instruments (Geron to RPRX and Pharmakon)

Out of nine publicly disclosed transactions spanning 2024 to early 2026, exactly one involves independent platforms jointly underwriting a single royalty position.

The aggregate publicly disclosed transaction value across these nine deals, taking midpoints and disclosed amounts, exceeds $3.5bn. Of that total, approximately $300m (the BridgeBio deal) involved true multi-manager syndication. That implies roughly 8-9% of disclosed transaction volume was syndicated in the strict sense. The remainder was executed by single platforms or internal multi-vehicle structures.

These figures carry an important caveat. The Gibson Dunn report notes that transactions not reported on EDGAR or not announced in press releases will be missed, and some clinical funding arrangements may not be disclosed if they fall below materiality thresholds. Under-reporting is likely more pronounced in Europe, where private issuers and privately negotiated royalty trades may never appear in US filings. The true syndication rate could be higher. But the public record suggests it is not the norm.

The missing mega round

The Gibson Dunn survey (2020-2024) shows that royalty financing can reach beyond $1bn, but the largest deals were concentrated in 2020-2023. In the 2024-2025 sample, the top end is Agios' $905m transaction, large by the standards of royalty monetisation but well below biopharma M&A transactions such as BioMarin's roughly $4.8bn Amicus acquisition.

Deal sizes in royalty financing generally do not require syndication for the largest specialist platforms. The market lacks the multi-billion-dollar transactions that serve as the forcing function for syndication in leveraged lending or acquisition finance.

Revolution Medicines' $2bn arrangement with Royalty Pharma in June 2025, comprising a synthetic royalty of up to $1.25bn plus a $750m loan, approaches the threshold where single-buyer capacity might be tested. Yet even here, one platform underwrote the full package.

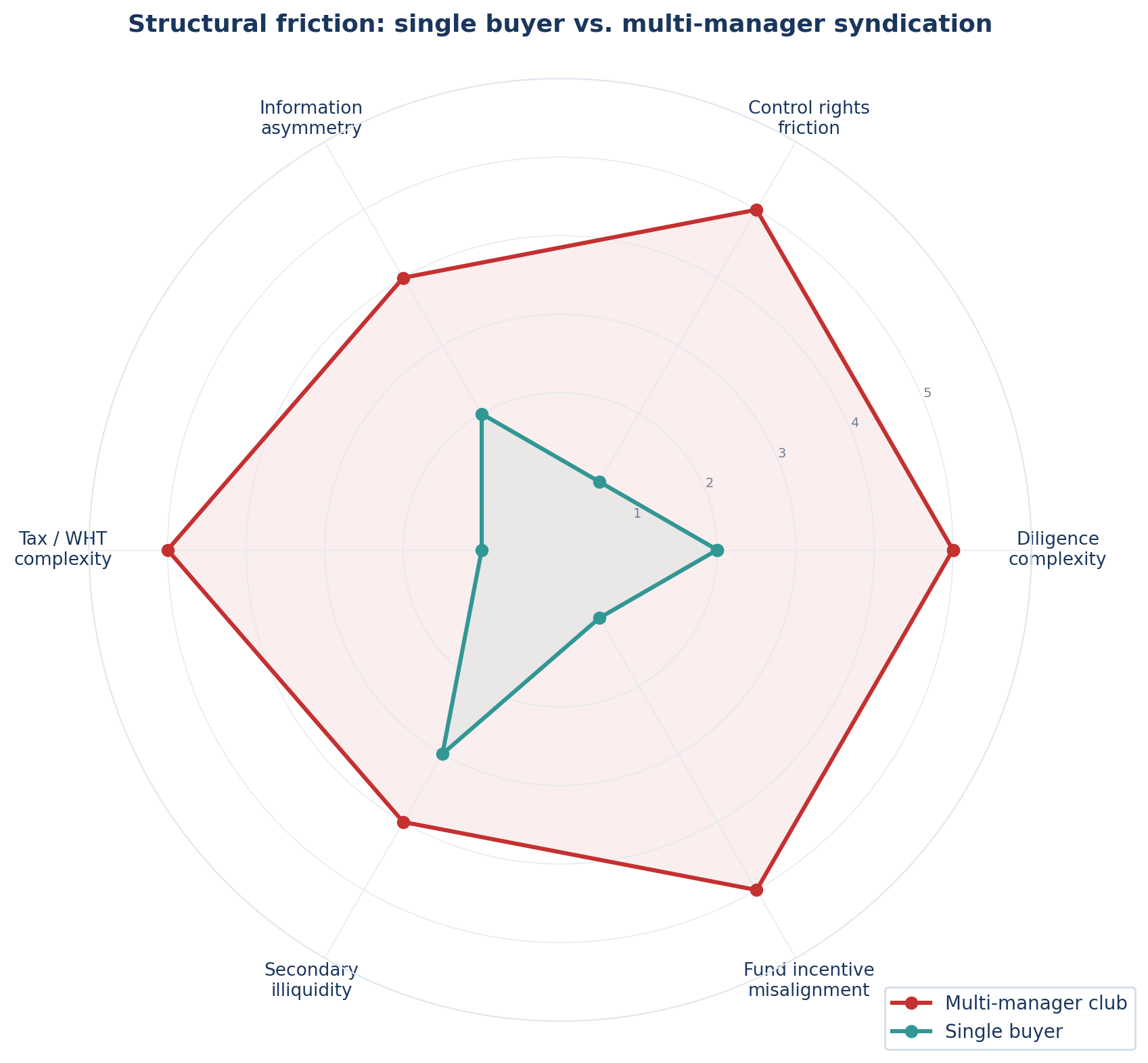

Why syndication is structurally harder than it looks

The barriers are less about whether one can split a royalty (the legal tools exist) and more about who controls diligence, monitoring and enforcement in an asset that is simultaneously contract-based, regulatory-exposed, operationally sensitive and often cross-border.

Control rights, true-sale integrity and enforcement coordination

Royalty purchase agreements commonly include explicit true-sale intent coupled with a security-interest fall-back. Esperion's agreement is explicit: sale of "accounts" under the UCC, financing statement perfection and a security-agreement fall-back if the sale is recharacterised. In a multi-manager syndicate, maintaining true-sale integrity while allocating enforcement and indemnity rights requires an agent or trustee and a priority and consent regime, adding negotiation time and cost.

The Castle Creek/Ligand agreement illustrates syndication-ready documentation: allocation percentages per purchaser, a Purchaser Representative (Ligand) binding purchasers to the representative's actions and "Required Purchasers" consent for amendments. These tools work, but they increase drafting complexity and create governance questions when one purchaser wants to amend, enforce or exit.

The diligence cost question: could syndication actually reduce it?

In the leveraged loan market, syndication partly works because diligence costs can be concentrated. The lead arranger conducts due diligence on behalf of the syndicate, produces a confidential information memorandum and invites participants to rely substantially on that work. Participants accept the information asymmetry in exchange for diversification and deal access. The lead retains a larger share to signal quality and maintain monitoring incentives, while participants benefit from reduced per-unit information production costs.

Could the same model apply to royalty financings? If the diligence work on a $300m royalty transaction is functionally the same whether one buyer or three buyers ultimately hold the position, then syndication should not materially increase total diligence cost. A lead runs the models, reviews the clinical data, negotiates the contract and produces an investment memo. Participants join at allocation. Per-participant diligence cost goes down, not up.

The difficulty is that royalty diligence differs from credit diligence in ways that make lead-and-participant structures harder to implement.

First, the asset is idiosyncratic. Leveraged loan underwriting benefits from rating agencies, established covenant packages and liquid secondary markets providing continuous price discovery. Royalty transactions lack all three. Each deal requires bespoke analysis of product-specific clinical, commercial, regulatory and patent data, the kind of diligence where reasonable experts can reach materially different conclusions on the same inputs. A participant in a leveraged loan syndicate can credibly rely on a credit rating and a CIM. A participant in a royalty syndicate is being asked to rely on another fund's commercial forecast of a specific drug's sales trajectory, a proposition many investment committees would not accept.

Second, ongoing monitoring creates a different cost structure. In leveraged lending, the administrative agent monitors financial covenants and distributes payments, a largely mechanical function. In royalty transactions, monitoring involves tracking regulatory developments, competitive dynamics, pricing changes, formulary decisions and licensee behaviour. This is closer to portfolio management than loan administration. When Esperion's agreement embeds a formal "Data Room" definition (anchored to a timestamp) and requires the seller to share material licensee correspondence, it creates an ongoing information flow that a single buyer absorbs efficiently but that a syndicate must distribute through governance mechanisms.

Third, competitive dynamics among specialist platforms raise the cost of sharing. Royalty platforms compete on diligence quality and origination relationships. Sharing a detailed investment thesis with a competing platform, as a lead arranger effectively does in loan syndication, risks commoditising the lead's analytical edge. In leveraged lending, the standardised nature of the product limits this risk. In royalties, where the edge lies in analysis of non-public clinical and commercial information, the cost of sharing is higher.

The diligence cost argument therefore cuts both ways. In theory, a lead-and-participant model reduces per-unit cost and expands the buyer base. In practice, asset idiosyncrasy, ongoing monitoring burden and competitive dynamics create barriers that do not exist in credit markets. The HCRx/Blue Owl partnership may represent one solution: a repeat bilateral relationship where both parties have developed sufficient trust and complementary capabilities to share positions without full duplication of effort.

The "many cooks" problem

Esperion's agreement constrains the seller's communications with the licensee unless purchaser consent is obtained, and requires sharing material correspondence. This is manageable with one counterparty but grows cumbersome with several. When multiple funds are involved, consent thresholds (unanimous, majority or supermajority) become a critical friction point because they determine whether the asset can be actively managed in adverse scenarios.

Cross-border tax frictions

Tax complexity is embedded in contract definitions. Esperion's agreement includes withholding documentation frameworks (W-8/W-9) and treaty references (the US-Germany double tax treaty, "Withholding Tax Refund" mechanics). In a multi-manager syndicate with mixed jurisdictions, withholding administration and refund allocation become an operational cost and a source of dispute, particularly when purchasers have different tax profiles (blockers, funds, insurance accounts) and different abilities to claim refunds.

Some revenue-interest structures show explicit debt-tax engineering. Esperion's earlier RIPA includes an obligation to prepay amounts after a period to prevent the instrument from constituting "applicable high yield discount obligations" under US tax rules. Multiple purchasers with divergent tax sensitivities make such engineering more contentious.

Risk allocation and secondary liquidity

Single-platform preference

Contracts frequently push substantial risk to the purchaser. Esperion's purchaser assumes risks from a "Credit Event" affecting the royalty stream (timing, amount, duration), subject to limited seller obligations. The agreement also includes strong non-reliance and risk-assumption language: the purchaser disclaims reliance beyond express representations. If a platform has performed deep diligence and is comfortable underwriting that risk, syndicating shares the upside while leaving the lead with disproportionate work and reputational exposure.

Secondary market: contemplated but thin

Assignment regimes exist. Esperion's RIPA defines "Eligible Assignee" using QIB and accredited investor concepts and AUM thresholds while carving out disqualified strategic buyers and activists under certain conditions. Transferability is contemplated, but thin buyer universes, bespoke covenants and confidentiality constraints keep secondary liquidity shallow. This weakens one traditional rationale for syndication: the ability to rebalance positions over time.

Fund incentives favour exclusivity

Purchaser representative structures (Ligand) and agent-for-purchasers structures (Hook SA LLC) indicate that where multiple economic interests exist, there is typically a single operational brain for the position. Royalty platforms differentiate on diligence and asset management and benefit from controlling meaningful cashflow positions for portfolio construction. Syndication across unrelated funds dilutes these advantages unless the ticket exceeds concentration limits or the risk profile is unusually binary.

Representative 2024-2026 transactions

| Issuer | Date | Size | Lead investor(s) | Syndicate | Structure | Key syndication-relevant detail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agios | May 2024 | $905m | Royalty Pharma | None | Single-buyer royalty purchase | Tiered royalty: 15% up to $1bn net sales, 12% above; Agios retains 3% above $1bn |

| Esperion | Jun 2024 | $305m (cap $518m) | OMERS / OCM | None | Single-buyer capped receivables | True-sale intent with UCC perfection; security-interest fall-back; consent controls on licensee communications; purchaser assumes credit-event risk |

| Geron | Nov 2024 | Up to $375m ($250m at close) | RPRX + Pharmakon | Two-provider | Clubbed royalty + 5yr senior secured loan | Multi-provider complementary instruments; royalty uses return-multiple cap; Pharmakon tranche draw structure |

| scPharmaceuticals | Aug 2024 | $75m | Perceptive Credit | None | Single-platform credit + RPR | Revenue participation right with "true sale" framing linked to credit agreement |

| ImmunityBio | Dec 2023 / May 2024 | $200m + $100m (post-approval) | Oberland Capital | Affiliated entities via Infinity SA LLC | Agented multi-purchaser | Revenue interest = net sales x applicable %; purchasers not individually named; agent structure lowers operational burden |

| BridgeBio | Jun 2025 | $300m (net ~$297m) | HCRx + Blue Owl | Two-manager club | Multi-manager syndication | 60% of EU royalties on first $500m annual net sales; 1.45x cap; partial and capped monetisation |

| Zenas | Sep 2025 | Up to $300m (4 x $75m) | Royalty Pharma | None | Single-buyer, milestone-tranched | Tranching as substitute for syndication: risk phased over milestones, not across buyers |

| Castle Creek / Ligand | Feb 2025 | Redacted | Ligand (Representative) | Multiple (Schedule I) | Multi-purchaser with representative | Allocation percentages per purchaser; "Required Purchasers" consent; governance mechanics visible even though economics redacted |

| Humacyte | May 2023 (amended 2024/25) | Up to $150m | Hook SA LLC (Agent) | TPC Investments III LP; TPC Investments Solutions LP | Agented multi-purchaser RIPA | Pro-rata purchasing; Purchaser Agent governance; revenue-interest framed as debt (debtor-creditor intent) |

Counterarguments: why syndication could be growing

A sceptical counterview is that syndication is already more common than the public record shows. The Gibson Dunn report notes methodological limitations: transactions not filed on EDGAR or not announced in press releases are missed, and sub-threshold clinical funding arrangements may go undisclosed. This is particularly relevant in Europe, where private issuers and privately negotiated royalty trades may never appear in US filings.

Tranching also substitutes for syndication. Zenas' up-to-$300m deal with Royalty Pharma uses milestone-contingent $75m tranches to phase risk rather than distributing it across buyers. This achieves risk mitigation without coordination costs.

Several conditions could increase true multi-manager syndication:

Larger deal sizes. If royalty monetisations consistently reach multi-billion-dollar scale (the Gibson Dunn survey shows $1bn-plus deals occurred in 2020-2023), club formation becomes economically necessary for concentration management. Revolution Medicines' $2bn arrangement approaches this territory.

Documentation standardisation. Purchaser-representative constructs (Ligand) and pro-rata/agent constructs (Hook SA LLC, Infinity SA LLC) show that the legal architecture is available. The gap is economic willingness to absorb governance overhead. If industry-standard covenant and reporting packages develop, analogous to those in leveraged loan documentation, the coordination tax drops.

New entrant categories. If insurers, private credit platforms and sovereign wealth funds enter the royalty market and seek scaled exposures, club deals become a natural compromise between speed and capacity. AnaptysBio's plans to spin off a dedicated royalty management company, separating Sagard-financed royalty assets from biopharma operations, illustrates the institutional evolution of the asset class.

A lead-arranger model transplant. If one or more platforms develop the infrastructure to function as lead arrangers, producing standardised diligence packages, retaining a meaningful share for incentive alignment and distributing participations, the per-deal coordination cost falls. This would require greater transparency between competing platforms than currently exists, but the HCRx/Blue Owl pattern shows it is feasible where complementary capabilities exist.

Assumptions and gaps

This analysis relies on public disclosure: SEC filings and issuer or investor press releases. It under-captures private EU transactions without US reporting obligations, fully private royalty trades and sub-materiality clinical funding arrangements.

Several filings embed key economics in redacted schedules. The Castle Creek/Ligand agreement references a Schedule I purchaser list and individual purchase prices that are not included in the public exhibit, limiting the ability to publish a complete participant list from the filing alone.

Syndication is used throughout in a strict sense: shared underwriting across different platform managers, distinguished from multi-entity participation within one platform. This distinction matters because it maps to different incentive and governance problems, even when the legal form looks similar.

Summary

Across nine representative publicly disclosed royalty transactions spanning 2024 to early 2026, exactly one involved independent platforms jointly underwriting a single royalty position, representing roughly 8-9% of disclosed transaction volume.

The reasons are practical rather than legal: idiosyncratic diligence requirements that resist the lead-arranger model used in credit markets, complex control rights, information asymmetry, cross-border tax friction and fund-level incentives that reward exclusivity. A theoretical case exists for cost-sharing through syndication, since the diligence work is largely the same regardless of how many buyers hold the position. But the non-standardised nature of the underlying assets and the competitive dynamics among specialist platforms create implementation barriers that do not exist in leveraged lending.

For syndication to become routine, the market would need larger deal sizes, more standardised documentation, a broader investor base and, perhaps most importantly, the development of trusted bilateral or multilateral relationships among platforms willing to share both economics and analytical work on a repeated basis.

The author is not a lawyer, investment banker or financial adviser. This article does not constitute investment or legal advice. Information is drawn from public SEC filings, issuer press releases and industry reports as cited. Readers should consult qualified professionals before making investment decisions.

Member discussion