The Art of Business (and the Business of Art)

For an industry so obsessed with metrics, dashboards, and KPIs, business is surprisingly full of art. Not just metaphorically—though there is, of course, a “craft” to negotiation or a “composition” to strategy decks—but literally. Go to any private bank in Zurich or London, and you’ll find walls lined with Rothkos, Baselitzes, or discreetly mounted photographs that cost more than your fundraising round. It is no coincidence. The people who steward capital tend to surround themselves with the things that signal permanence, refinement, or—most ironically—vision.

The relationship between art and capital is old, opaque, and frequently misunderstood. It’s not about taste. It’s about value, and its many shadows: perceived value, projected value, the kind that exists because someone believes it ought to. Sound familiar? It should. Venture capital operates on the same logic. Early-stage biotech, especially, is just one degree removed from conceptual sculpture—an attempt to assign price to possibility.

But for founders, the case for art is more than symbolic. It’s a tool—to think, to reflect, to reframe.

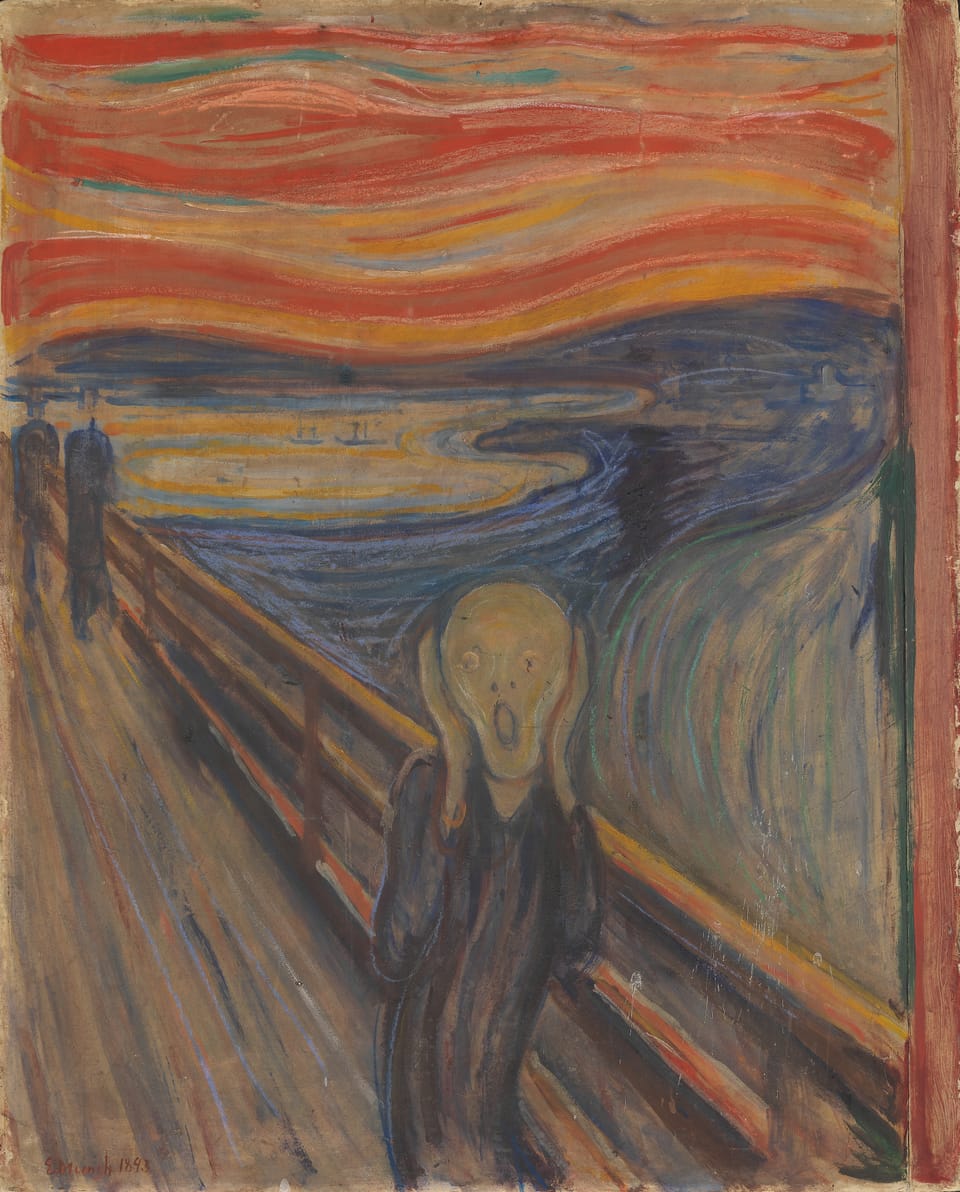

Start with Edvard Munch’s The Scream. One of the most iconic images in visual culture, it is frequently reduced to meme fodder: the figure clutching its head, mouth agape, panic personified. But the backstory is deeper—and oddly biomedical. Munch described the painting’s inspiration not as a single moment of emotion, but a physiological reaction: “I felt a great scream pass through nature… I sensed an infinite scream passing through the landscape.” Scholars have linked this to his own experiences with anxiety, synesthesia, and familial illness—his mother and sister died young of tuberculosis. The figure in The Scream is not just emotive; it is clinical, a portrait of psychic pressure made visible.

This is healthcare art in its purest form: abstract, ambiguous, but undeniably diagnostic.

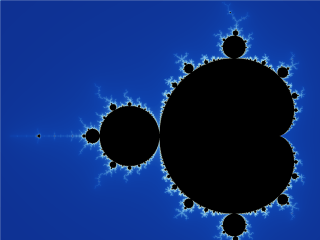

Or consider the Mandelbrot set—the swirling, recursive visual pattern that became the symbol of fractal geometry. It emerged not from an artist’s studio but from IBM’s laboratories in the 1970s. Benoît Mandelbrot used it to describe natural chaos: coastlines, blood vessels, stock markets. What looks like abstract art is, in fact, an actuarial x-ray—a visual model of systems too complex for linearity. And yet, it is beautiful. Founders building in complex environments—drug discovery, AI, longevity—are not unlike Mandelbrot: they chase patterns in chaos. A fractal doesn’t just describe risk. It looks like risk.

Art teaches us how to work with ambiguity. It requires taste, not certainty. In biotech, you rarely have full visibility—clinical data arrives late, regulators behave unpredictably, and science evolves faster than policy. Founders trained only in spreadsheets often flinch at this. But those who study art—who understand that contrast, rhythm, or even silence can convey meaning—develop a different kind of literacy. They learn to sit with the unknown, to interpret signals without always needing a p-value attached.

It’s no accident that some of the most perceptive investors are collectors. Art demands a kind of long-horizon thinking. It doesn’t cash flow. It doesn’t pay dividends. Its value is determined in markets that are relational, opaque, and emotional. Just like early-stage biotech.

In fact, some private banks and family offices no longer just hang art—they invest in it. There are entire vehicles now that securitize paintings, fractionalize collections, or back artists as one might back startups. The logic is the same: identify emerging value before the market does. Curate carefully. Hedge against inflation. And above all, tell a story that justifies the price.

Which brings us to the founder’s opportunity. Art can offer escape, yes. But it also offers calibration. A way to remember that not all value is captured in metrics. That a good story, elegantly told, can change perceptions. That beauty—even in a system as brutal as healthcare—still matters.

So go to a museum. Hang something strange in your office. Learn the difference between Caravaggio and Kandinsky. Not because you want to impress LPs—but because somewhere between the brushstrokes, you may find a new language for what you’re building.

You might even find yourself screaming a little less.

Member discussion