The Outsourcing Hangover: CROs, CDMOs and a Capacity Conundrum

“Excess capacity” – not a phrase one expects to hear in a high-growth industry riding on the coattails of pharmaceutical innovation. Yet in the once-overheated world of contract research and manufacturing, signs of a glut are emerging. Europe’s gleaming labs and China’s biotech parks, which expanded feverishly during the pandemic and funding boom, now face a sobering question: have they built more capacity than the market can fill? This deep dive assesses whether there is overcapacity in the Contract Research Organization (CRO) and Contract Development & Manufacturing Organization (CDMO) sectors in Europe and China as of mid-2025. We examine the number and scale of providers by segment and modality, the supply-demand dynamics (historical demand growth vs. infrastructure expansion), and the utilization challenges. We also chart the M&A spree of 2022–2025, where deal-hungry investors sought to turn oversupply into opportunity. The picture that emerges is one of an industry wrestling with a classic economic cycle: a pandemic-fueled outsourcing boom, followed by a hangover of excess labs and idle bioreactors – albeit one tempered by resilient long-term fundamentals.

From Boom to Bottleneck: A Fragmented Industry Scales Up

Not long ago, CROs and CDMOs were scrambling to keep up with demand. The 2010s saw an explosion of new drug R&D programs – the number of molecules in development more than doubled in a decade, with pipelines for both small-molecule and large-molecule drugs growing at 5–12% annually (contractpharma.com). By 2020–21, venture capital cash gushed into biotech startups, all of whom needed labs, scientists, and factories-for-hire. When COVID-19 struck, it turbocharged the trend: governments and pharma companies threw billions at contract manufacturers to produce vaccines and therapies at unprecedented speed. CROs, meanwhile, geared up to handle a wave of trials for new vaccines, antivirals, and the ensuing biotech boom. In short, demand for outsourced pharma services hit an all-time high – and the industry responded in kind.

Hundreds of providers sprang into action. The CRO sector encompasses everything from boutique preclinical labs to global clinical trial managers. The CDMO side ranges from small pill-makers to giant biologics factories. In Europe and China, the ecosystem is vast and varied: Europe’s legacy of fine chemical and biologics production spawned many medium-sized CDMOs, while China’s meteoric rise in pharma gave birth to integrated players like WuXi AppTec (spanning CRO to CDMO) and a plethora of specialists.

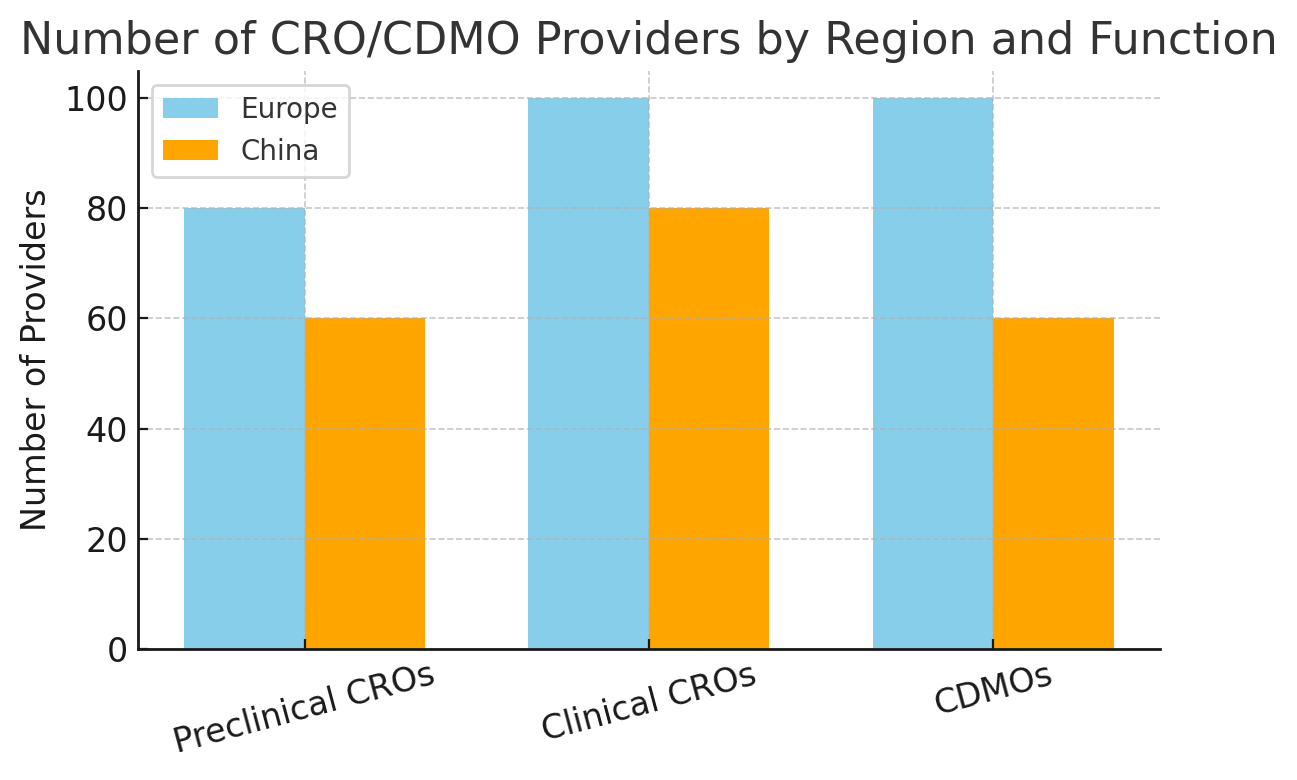

By 2023, the global count of active CDMOs had swelled to nearly 400 companies, a ~20% jump in just three years. The CRO ranks are even larger, with well over a thousand organizations worldwide (albeit dominated by a top tier of multinationals). Figure 1 illustrates the number of providers in Europe and China by function, highlighting both regions’ vibrant mix of research-focused CROs and manufacturing-focused CDMOs.

Figure 1: Number of CRO/CDMO providers by region and function (preclinical research CROs, clinical trial CROs, and manufacturing CDMOs). Europe hosts a slightly larger number of contract manufacturers and research organizations, reflecting its mature pharma base, while China’s rapid growth has built a substantial cadre of CROs and CDMOs as well. (Numbers are illustrative estimates.)

Segmentation by modality further reveals how capacity is distributed. In small-molecule drug manufacturing (think traditional pills and chemical APIs), Europe has long had extensive capacity (in countries like Italy, Spain, and Ireland), now joined by increasing high-quality capacity in China. For biologics (monoclonal antibodies, recombinant proteins), large Western CDMOs such as Lonza (Switzerland) and Boehringer Ingelheim (Germany) historically led the way, but China’s entrants like WuXi Biologics have aggressively expanded – global biologics CDMO revenues jumped from about $13 billion in 2018 to $29 billion in 2022 (frost.com), and China is taking a growing slice.

In cutting-edge cell and gene therapy (CGT) manufacturing, dozens of new players have popped up in the last five years, from Europe’s Catalent (with dedicated gene therapy sites in Belgium and Italy) to China’s burgeoning cell therapy CDMOs. The industry’s “dual-engine” growth model is evident: even as traditional small-molecule services grow steadily, new modalities like CGT, mRNA, and antibody-drug conjugates have driven a wave of specialized capacity investments. For example, high demand for complex peptides like GLP-1 (the basis of diabetes and obesity drugs) spurred Novo Nordisk to seek more capacity – even exploring acquisition of major CDMO lines (frost.com). In short, capacity has expanded across the board: more labs for early research, more facilities for clinical trial material, and bigger plants (with bioreactors of 10–20,000 liters) for commercial manufacturing.

Supply vs. Demand: When Expansion Outruns Need

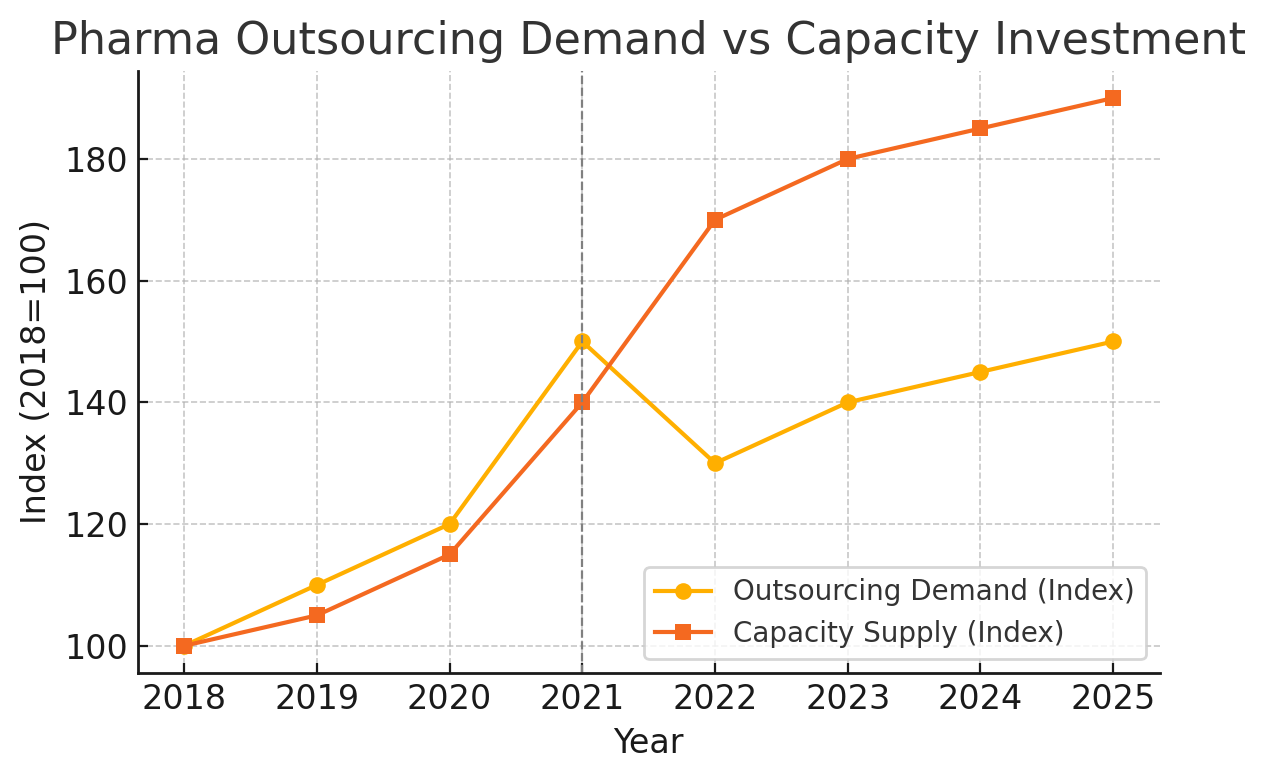

Economics 101 teaches that when supply overshoots demand, a reckoning follows. By 2023, cracks in the CRO/CDMO boom narrative were becoming visible. Demand growth faltered just as a surge of new capacity came online. Figure 2 shows a high-level index of “outsourcing demand” vs. “capacity investment” over the past years. The orange line (capacity) shoots up sharply around 2021–2022, reflecting the building spree – new production suites, hiring sprees, and acquisitions of facilities. The yellow line (demand) tells a different story: after the pandemic peak, demand (proxied by biotech funding and pipeline growth) dipped in 2022 and has only partly recovered.

Figure 2: Pharma outsourcing demand vs. capacity investment (indexed, 2018=100). Demand for CRO/CDMO services (yellow) grew rapidly through 2021 but then dipped as biotech funding waned and COVID-related work shrank in 2022 (biospace.com) . Meanwhile, industry capacity (orange) continued to climb, fueled by heavy investment in 2020–2022. The result: a gap between available capacity and work to fill it.

Several factors contributed to this temporary glut

Pandemic whiplash

After 2021’s vaccine windfall, COVID-related manufacturing orders fell off a cliff. Contract manufacturers that heroically added vaccine vial filling lines and boosted API output suddenly found those lines underutilized by late 2022. As one analyst quipped, “once the demand shrank…some were left to fill their expanded capacity” (contractpharma.com). Government stockpiling gave way to oversupply; CDMOs that had bet big on continued COVID product contracts had to scramble to replace the lost volume.

Biotech funding downturn

The easy money era ended in 2022. Rising interest rates and risk aversion led to a sharp pullback in biotech financing. Funding for emerging biopharma in H1 2023 was roughly half the 2020 peak. Too many biotechs chasing too little capital became the theme (contractpharma.com). Consequently, small clients started delaying or cancelling projects – directly hitting CROs and CDMOs. Lonza, for example, noted “lower growth in early-stage services due to biotech funding restraints” (biospace.com) and cut its 2023 sales outlook. With less venture cash, emerging pharma clients trimmed R&D pipelines, triaging their use of external labs.

Geopolitical and regulatory drag

Especially relevant to China’s CDMOs, geopolitical tensions created uncertainty in demand. Western pharma began re-evaluating reliance on China for sensitive manufacturing. The specter of “decoupling” led some US/EU firms to hedge away from Chinese service providers (contractpharma.com). China’s domestic pharma market also hit headwinds – an economic slowdown and stricter anti-corruption measures dampened growth in late 2023. As a result, some Chinese CRO/CDMOs found that global orders slowed, and they had to refocus on local clients. (Notably, industry advocates warned that suddenly cutting off Chinese CDMOs would “harm millions of patients” and require 8 years to find alternative capacity (fiercepharma.com) – highlighting how much capacity China does contribute to global supply.)

Overenthusiastic expansion into new modalities

A couple of years ago, cell and gene therapy CDMOs faced waiting lists; today, they advertise available slots. VintaBio’s CEO observed in mid-2023 that “the biggest trend by far in the CDMO space is excess capacity,” specifically citing cell/gene therapy facilities (bioprocessintl.com). So much money poured into advanced therapy manufacturing in 2020–2022 that supply overshot the nascent demand. These facilities are state-of-the-art – but many are now competing to fill suites as the pipeline of approved cell/gene therapies (and funded trials) is still maturing. As one industry insider put it, capacity doesn’t equal capability – many newer entrants built rooms but lack the track record to attract enough clients.

The net effect has been softer utilization rates and pricing pressure. By late 2023, CRO and CDMO revenue growth had slowed markedly. Big players like Catalent issued profit warnings and saw investor activism as they struggled with under-used facilities and cost overruns. Smaller firms, lacking diversified client bases, were hit even harder – some reduced staff or delayed expansion plans.

An investment banker noted that trial volume in China’s clinical CRO market actually declined in 2022–2023 due to price competition, though it stabilized by 2024 (lek.com). In other words, excess capacity translated to discounting and consolidation. One clear indicator: China’s overseas clinical trials sponsored by Chinese firms dropped ~15% in 2023 (vs 2022) before inching up again – a dip in activity that many CROs felt in their order books.

None of this is to say the outlook is doom and gloom. In fact, most insiders see the 2023–2024 slump as a cyclical “breather” – a period of re-alignment before growth resumes (contractpharma.com). The fundamental drivers (Big Pharma’s push to outsource, an ever-expanding range of therapeutic modalities, and the cost advantages of specialized contractors) remain intact.

But the message was clear: after years of exuberance, the CRO/CDMO sector had to work off the excess. In effect, 2023 became a year of digestion – digesting surplus inventory (one investor spoke of a “post-COVID overhang” of unused stock and idle tanks), and digesting the surge of new capacity by finding creative ways to fill it. How? By cutting deals and partnering up – which brings us to the recent M&A trend.

Consolidation as a Cure: M&A in 2022–2025

When organic demand falls short, Mergers & Acquisitions often rise to the occasion. The past three years have indeed seen a wave of deal-making as CROs and CDMOs sought scale, new capabilities, or simply an exit strategy for underutilized assets. Both strategic buyers (big pharma services firms) and private equity swooped in, sensing an opportunity to consolidate a fragmented market and prepare for the next upturn. As one industry report noted, investors remain “bullish on quality outsourcing platforms,” paying premium valuations even amid recent headwinds (cdn.hl.com).

The logic: combining companies can eliminate duplicate overhead, broaden service offerings (one-stop-shop appeal), and absorb excess capacity by concentrating projects into the best-equipped facilities.

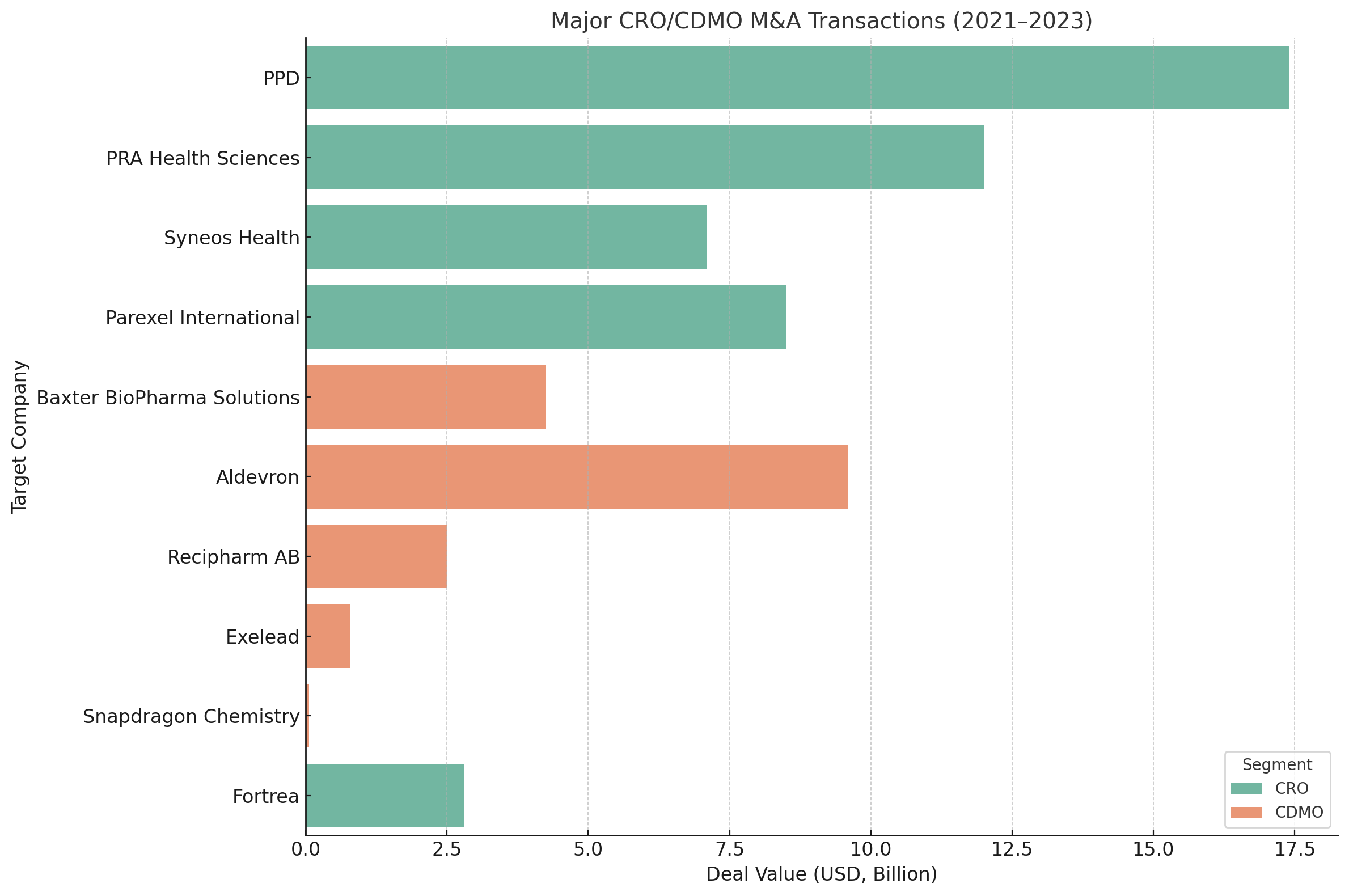

Table 1 highlights selected major M&A transactions in the CRO/CDMO arena since 2021. These deals underscore a few themes: mega-deals among CRO giants, private equity carving out pharma company divisions and taking them private, and targeted acquisitions in specialized niches (often advanced therapy manufacturing).

Table 1: Notable CRO/CDMO M&A deals in recent years. Big CRO consolidations in 2021 (Thermo Fisher–PPD, ICON–PRA, EQT–Parexel) reshaped the clinical research landscape, creating mega-CROs. 2022–2023 saw private equity carve out divisions like Baxter’s injectable CDMO unit for $4.25Breuters.com. China’s Asymchem attempted to acquire U.S.-based Snapdragon Chemistry, but the deal was abandoned after U.S. security review – a sign of geopolitical scrutiny in pharma deals. Valuations remain robust for coveted assets, with CDMO deals averaging EBITDA multiples in the mid-teens to 20× range.

A few strategic rationales stand out from these deals

Bolstering Capabilities

Many acquisitions aimed to fill a gap in capabilities or capacity. For instance, Merck KGaA’s purchase of Exelead gave it a foothold in mRNA vaccine production (lipid nanoparticle technology) to capitalize on the post-COVID mRNA pipeline. Danaher’s buy of Aldevron brought in plasmid DNA and mRNA raw material capabilities, anticipating growth in gene therapies. In China, WuXi Biologics’ acquisition of a Pfizer biologics plant in Hangzhou (announced in 2021) instantly added 50,000+ liters of bioreactor capacity, accelerating its scale-up. In a supply-constrained world, these moves made sense – but as capacity excess emerged, some deals turned to tucking in oversupply (e.g. Catalent’s rumored talks to sell off excess fill-finish sites to Novo Nordisk).

Horizontal consolidation

The CRO world saw big players combining to achieve global reach and economies of scale (ICON with PRA, creating a $19B-market-cap giant in clinical trials). The theory is that a broader geographic footprint and service portfolio makes a CRO more attractive to global pharma clients seeking fewer outsourcing partners. Similarly, CDMO consolidation (Recipharm taken private to merge with other assets; Thermo Fisher buying PPD to add clinical research to its lab services) reflects clients’ preference for “one-stop” providers. A recent analysis predicts the top 5 CDMO companies could control ~40% of the market by 2030, up from ~15% in 2023– a dramatic concentration driven by such M&A.

Private equity “buy and build”

The steady cash flows of pharma services (often backed by multi-year contracts) attracted private equity in droves. Firms like EQT, Carlyle, and Advent not only executed multi-billion acquisitions (Parexel, Recipharm, Baxter’s unit) but also pursued roll-ups of smaller specialists. The goal: create a platform that can command higher multiples upon exit, by being a scaled, diversified outsourcing partner. For example, after Recipharm went private, it acquired virology CDMOs in 2022 to expand into viral vectors. These PE owners are betting that once the current lull passes, they’ll own streamlined organizations ready to meet renewed demand – or to sell to an even larger strategic suitor.

Geographical hedging

Interestingly, some deals also serve to hedge geopolitical risk. A case in point is the failed Asymchem–Snapdragon deal. Asymchem (a leading Chinese CDMO) sought a U.S. foothold by acquiring Massachusetts-based Snapdragon Chemistry, but it was stopped by CFIUS (U.S. Treasury) over national security concerns. Shortly after, Snapdragon found a domestic buyer (Cambrex, a U.S. CDMO). This saga shows that Chinese firms are keen to globalize – and Western firms/authorities are selective about it. Conversely, Western CDMOs have invested in China (Lonza, for instance, opened a big Guangzhou site in 2022). The result is a kind of cross-border capacity insurance: having facilities in both East and West to assure clients that projects can flexibly navigate trade restrictions.

Clusters and Capacity: Europe vs. China in Focus

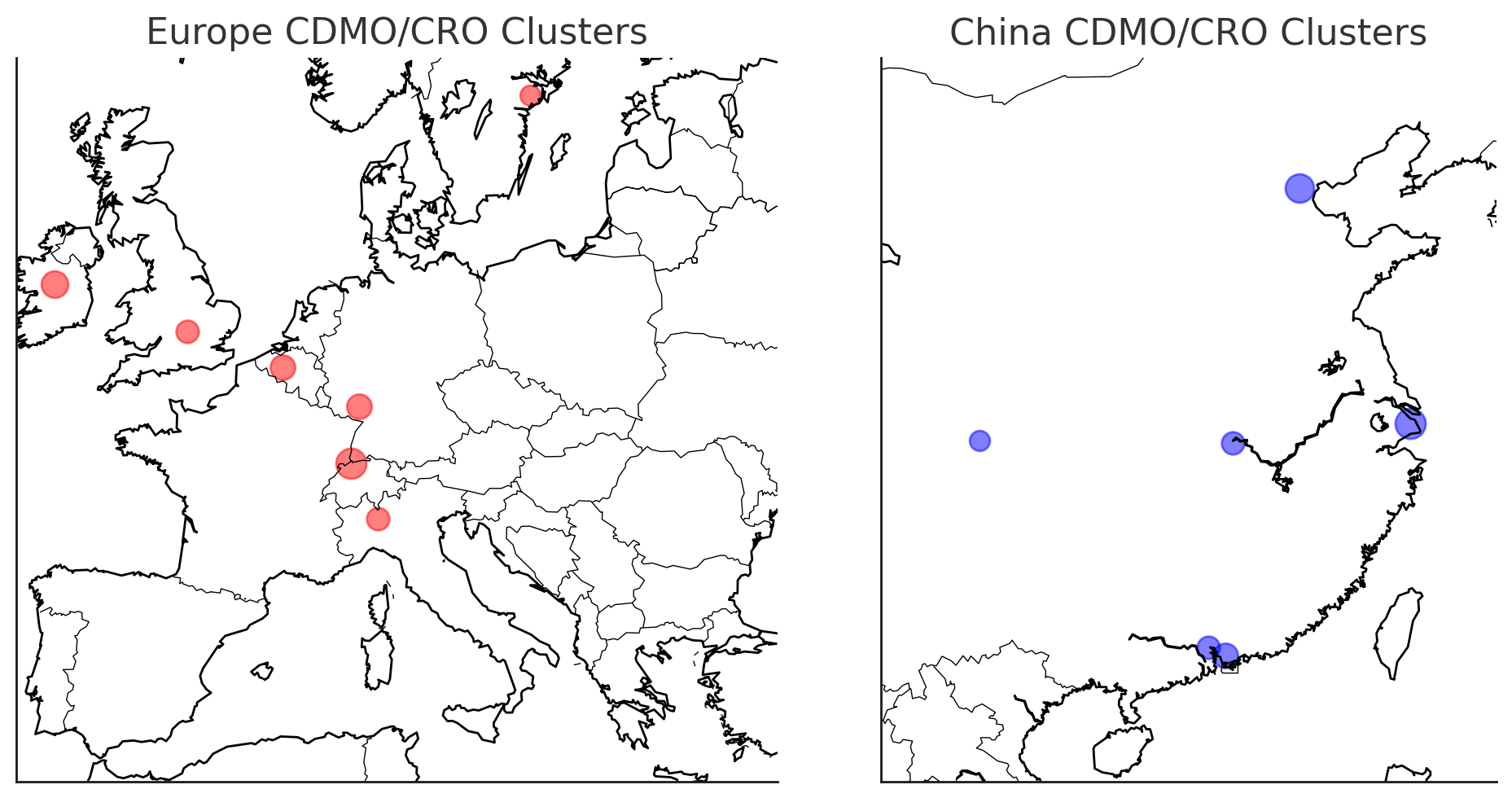

From a bird’s-eye view, Europe and China each boast distinct geographic clusters of CRO/CDMO capacity. Europe’s contract manufacturing strength concentrates around historic pharma hubs – think of Basel in Switzerland (home to Lonza and others), southern Germany and Austria (chemical API sites and biologics plants), Ireland (a magnet for pharma manufacturing with players like Thermo Fisher and WuXi Biologics’ new Irish site), northern Italy and France (sterile injectable and vaccine production), and the UK (Cambridge/Oxford for CRO research, and some manufacturing in Wales and Northern England).

China’s capacity, on the other hand, clusters in its major biotech ecosystems: the Yangtze River Delta around Shanghai (where WuXi AppTec, WuXi Biologics, and myriad CROs thrive), the Beijing–Tianjin corridor (many state-of-the-art biologics plants and clinical CRO HQs), and the Guangzhou–Shenzhen area in the south (growing especially in cell therapy and small-molecule API production). Other Chinese cities like Wuhan and Chengdu are also emerging hubs.

Figure 3: Geographic “heat map” of CRO/CDMO capacity clusters in Europe (left, red circles) and China (right, blue circles). Larger circles indicate regions with higher concentrations of providers and capacity. Europe’s activity is dense in areas like Switzerland/Germany (“Pharma Valley”), Ireland, Northern Italy, and the UK’s Golden Triangle, reflecting long-established pharma manufacturing zones. China’s capacity is heavily clustered in the Shanghai region and Beijing/Tianjin, with significant nodes in Guangdong (Shenzhen/Guangzhou) and emerging sites inland. (Visualization is illustrative.)

This geographic distribution matters for overcapacity: some clusters face more slack than others. In Europe, for example, Ireland’s large molecule CDMOs have been quite full thanks to biologics demand (some even expanding further). But certain small-molecule API sites in Southern Europe have seen utilization drop as generic drug pricing pressures bite – a sign of overcapacity in older chemistry capacity. In China, Shanghai’s CROs are still busy with global projects, but provincial CROs serving local generic manufacturers report more idle time as China’s regulatory environment tightens and redundancies exist across many similar service providers. Both regions also contend with talent and cost inflation, meaning underutilized facilities quickly become margin-drags.

One positive consequence of the cluster effect: local cooperation and repurposing. Within clusters, if one firm’s facility is underused, often a neighbor can step in as a client or even sub-lease space. For instance, in the BioValley spanning Switzerland, France, and Germany, there have been cases of one CDMO partnering with another to fill surplus capacity for a big project (sharing the work). In China’s Zhangjiang Pharma Valley (Shanghai), CROs and biotech incubators form alliances so that if startups can’t raise funds to continue a project, the CRO shifts those scientists to another client’s work to avoid layoffs – absorbing the capacity flexibly. These micro-adjustments soften the impact of overcapacity by redistributing work within the network.

Outlook: Green Shoots Through the Overcast Sky

Is the current overcapacity a temporary raincloud or a climate shift? The consensus leans toward the former. Early 2024 data showed some “green shoots”: biotech funding appeared to bottom out and tick up (contractpharma.com), and Big Pharma – flush with cash from pandemic profits – resumed sourcing projects to CROs (for example, Pfizer and others are outsourcing more R&D to cut internal costs). As one seasoned observer noted, the underlying demand drivers remain very strong despite the “softness” in 2023. Global pharma R&D spending is still on track to grow mid-single-digits annually, and a higher share of that is outsourced each year. The backlog of novel therapies (mRNA vaccines for other diseases, gene therapies, oncology biologics) virtually guarantees that the unique capacity built recently (high-containment biologics suites, viral vector labs) will eventually be well utilized – just perhaps a year or two later than originally planned.

However, the shakeout will leave its marks. Not every provider will survive a sustained drought of projects. We may see some smaller CROs and CDMOs exit or be acquired at bargain prices if they cannot fill their capacities in 2024. The market is already adjusting via price: sponsors (the pharma clients) can now negotiate better rates for some services than during the peak, which will compress margins for suppliers until demand catches up. Utilization rates, which in pharma manufacturing run lower than consumer goods even at the best of times (~30–40% is common for pharma plants vs >80% in most industries), will slowly improve as the excess capacity gets absorbed by new programs.

Policymakers have also taken note. Europe, for instance, launched initiatives to “reshore” critical medicine production, partly to avoid dependence on overseas suppliers (contractpharma.com). This could channel more work to European CDMOs (using up capacity) – the paradoxical effect of a previous over-reliance on cheapest suppliers. China, for its part, is doubling down on innovation to ensure domestic pipelines fill domestic CDMOs; the Frost & Sullivan “Blue Book” report highlights how China’s CDMOs are pivoting to higher value R&D services and “dual-path” models (high-end specialty + large-scale orders) to keep their fermenters busy. In short, the industry is adapting on both demand and supply sides.

The CRO/CDMO sector is learning a lesson in corporate strategy the hard way. Overexpansion – like over-hiring or overbuilding in any business – eventually forces a correction. But unlike some industries where a bust leaves rusting factories, pharma outsourcing has a tailwind: the inexorable march of science. Today’s overcapacity in a vaccine plant might find purpose when the next pandemic (or cancer vaccine) emerges. The idle analytic lab in Shanghai can be repurposed for the exploding field of AI-driven drug screening. Excess is relative and not permanent – given time and innovation, demand will likely catch up.

So, is there overcapacity in Europe’s and China’s outsourcing sectors in mid-2025? Yes, in the near-term – by multiple accounts, capacity growth outpaced demand from 2019 to 2024 (bioprocessintl.com), leaving some sites underused. But this is a cyclical and uneven phenomenon: top-tier, well-run facilities still brim with projects, while marginal players feel the pinch. As the sector rebalances through consolidation and growth, the current surfeit may prove to be a savvy investment in future capability.

In the meantime, pharma firms enjoy the buyer’s market for services, and CROs/CDMOs must run tighter ships, focus on quality (not just quantity of capacity), and perhaps whisper a humble prayer that the next wave of drugs arrives sooner rather than later. In the long run, today’s overcapacity could be tomorrow’s life-saving flexibility – a surplus turned into a strength once the pipeline floods again. After all, in the drug development universe, as in economics, feast and famine are never far apart.

Member discussion