The Middlemen’s Middlemen: How Fund-of-Funds Make Money by Investing in People Who Invest in Other People

Venture capital, like most human activities involving large sums of money and delayed gratification, has developed a hierarchy. At the top: the VCs—those chiselled, deal-sourcing demigods who turn PowerPoints into paper unicorns. But behind them, a quieter, more layered breed exists: the fund-of-fund. It is a curious construct—an investor that invests in the investors who invest in you.

Welcome to the world of double fees, career LPs, and secondhand conviction. It may sound like financial nesting dolls—but done well, it offers access, risk mitigation, and returns that are surprisingly real.

What Is a Fund-of-Funds?

A fund-of-funds (FoF) is a pooled investment vehicle that allocates capital across multiple venture capital or private equity funds. Rather than backing startups directly, a FoF backs the managers who do. Think of it as a portfolio of portfolios—an institutional sampler platter for those who prefer a bit of diversification with their due diligence.

FoFs exist to solve a problem: too many choices, not enough insight. Institutional investors (pension funds, endowments, family offices) want exposure to venture capital, but lack the bandwidth or access to vet dozens of funds across geographies, stages, and sectors. Enter the FoF manager: part allocator, part relationship broker, part risk psychologist.

The Double Fee Dilemma

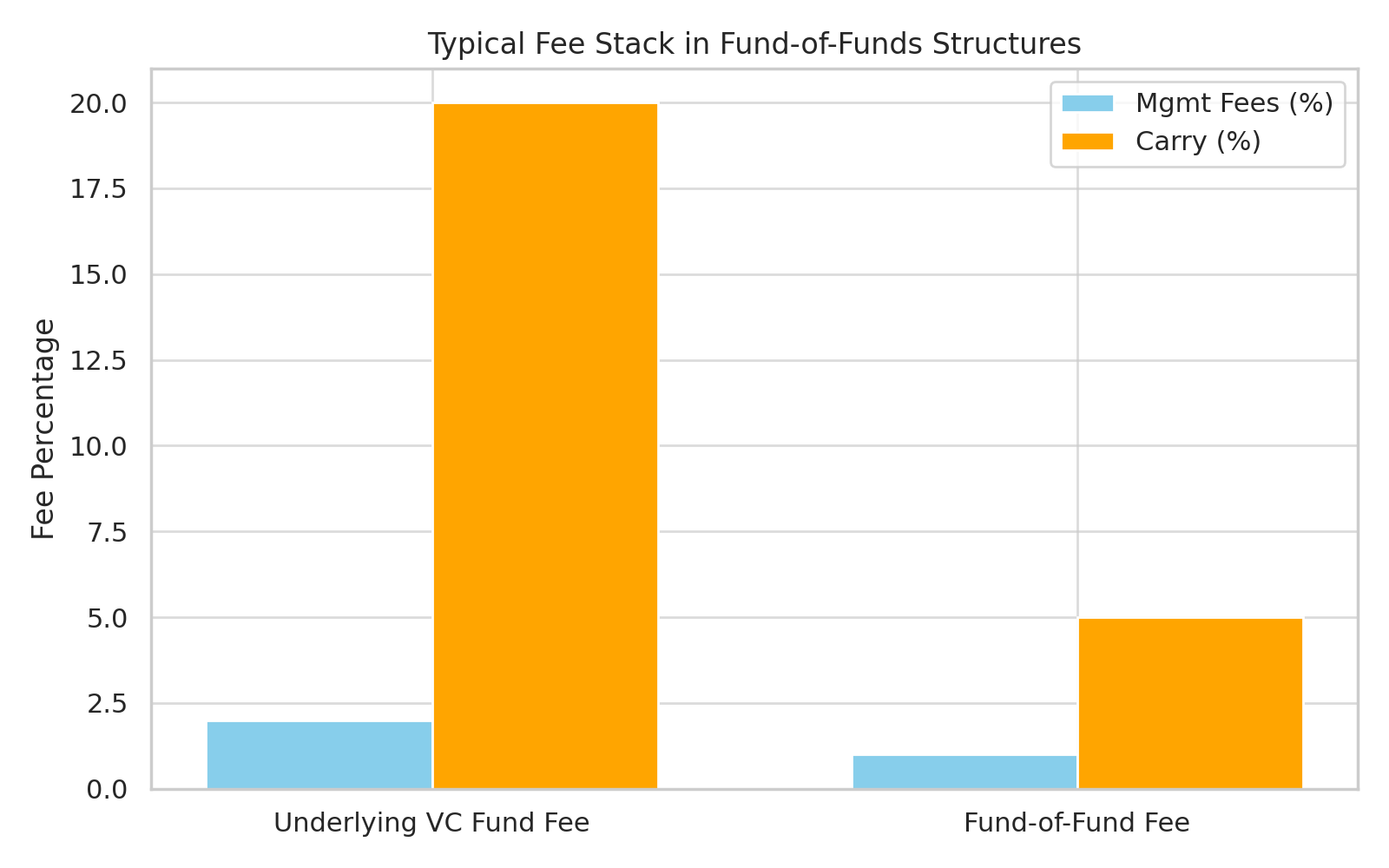

Naturally, nothing in finance comes for free. The most notorious feature of FoFs is the double fee structure: investors pay fees at both layers—first to the FoF, then to the underlying VC funds.

Here’s what that looks like:

On average:

- The underlying VC fund charges 2% per year in management fees and 20% carry (a cut of the profits).

- The FoF charges 1% per year and 5–10% carry, typically on net returns after the VC fund’s fees.

So yes: you’re paying a manager to pick managers, who then pick startups. And they all take a slice.

But as with many things in finance, expensive is not always stupid.

Why Do Fund-of-Funds Exist?

1. Access

The best-performing VC funds often don’t need your money. They’re oversubscribed. They’re closed. They’re run by GPs with a waiting list longer than the Sagrada Familia. FoFs, however, often have pre-existing relationships, early LP rights, or inside baseball—earned by anchoring a first fund years ago.

This access alone can be worth the cost. Getting into Sequoia, Accel, or a top-tier European micro-fund may require more than a wire transfer—it requires history.

2. Diversification

LPs love diversification. A single VC fund might write 30 checks. A fund-of-funds might hold 15 of those VC funds. That’s hundreds of companies across stage, geography, and strategy. For institutions with a fiduciary duty not to get fired, that’s a feature, not a bug.

3. Manager Vetting

Good FoFs do real work: tracking GP performance across cycles, understanding team turnover, dissecting DPI vs. TVPI, and catching red flags hidden in footnotes. They also serve as early fire alarms—if a fund stops getting FoF backing, that’s usually worth a raised eyebrow.

4. Back Office and Reporting

FoFs handle admin, audits, cash flow forecasting, capital calls, and LP reporting. For smaller institutional investors, this makes venture exposure palatable—like buying a pre-washed salad mix instead of growing your own kale.

Examples of Venture-Oriented FoFs

Some household names in this niche include:

- SVB Capital – Despite recent headlines, their FoF arm still deploys across a broad portfolio of early-stage and crossover VCs.

- AlpInvest (part of Carlyle) – Manages multi-billion FoF strategies across private equity and venture.

- Northleaf Capital – A Canadian powerhouse with dedicated venture FoF exposure, especially in the U.S.

- Industry Ventures – Not just a secondary buyer, but a FoF investor across early- and growth-stage VC.

- Top Tier Capital Partners – SF-based, long-time FoF with good access to Sand Hill Road royalty.

In Europe, newer names like Blue Horizon, Luna Ventures, and various fund-of-fund spinouts from sovereign wealth or pension capital are gaining ground.

But… Do They Actually Deliver Returns?

Ah, the million-euro question.

The short answer: yes, if done correctly. The long answer: it depends on access and discipline.

Cambridge Associates has shown that top FoFs can deliver net IRRs in the 10–14% range, which—while below top-quartile direct VC—is still competitive, especially on a risk-adjusted basis. More importantly, they tend to offer smoother return distributions, fewer zeros, and better DPI (cash returned) due to structured liquidity strategies and secondaries.

They may not deliver the eye-popping 5x of a unicorn bet—but they rarely disappear in a puff of markdowns either.

The Downside: Fees, Distance, and Time

FoFs are slow. They commit capital to VC funds, which then deploy into startups, which then grow, raise, and hopefully exit. This creates a lag effect—it can take years to even know if the vintage was any good.

Also: the distance from the asset is real. As an FoF LP, you don’t know the founders. You don’t influence boards. You don’t get that warm, fuzzy “I backed them early” feeling. You're just another layer of capital—removed, abstract, but (hopefully) compounding.

Conclusion: Should You Use a Fund-of-Funds?

If you are:

- An institution looking for exposure across top-tier VCs without chasing every GP personally;

- A family office without the infrastructure to vet and manage 20+ fund relationships;

- A new LP building vintage diversification without losing your shirt in your first cycle…

Then yes, a FoF can be a smart way to enter the market.

But go in with open eyes. Know the fee stack. Demand transparency. Ask about secondary access. Ask how they win allocations. And ask what they don’t invest in—and why.

Because if you’re going to pay fees on fees on fees… you’d better make sure there’s something worth stacking under them.

Member discussion