Global Clinical Trial Outlook for Late 2025 – Key Readouts and Market Implications

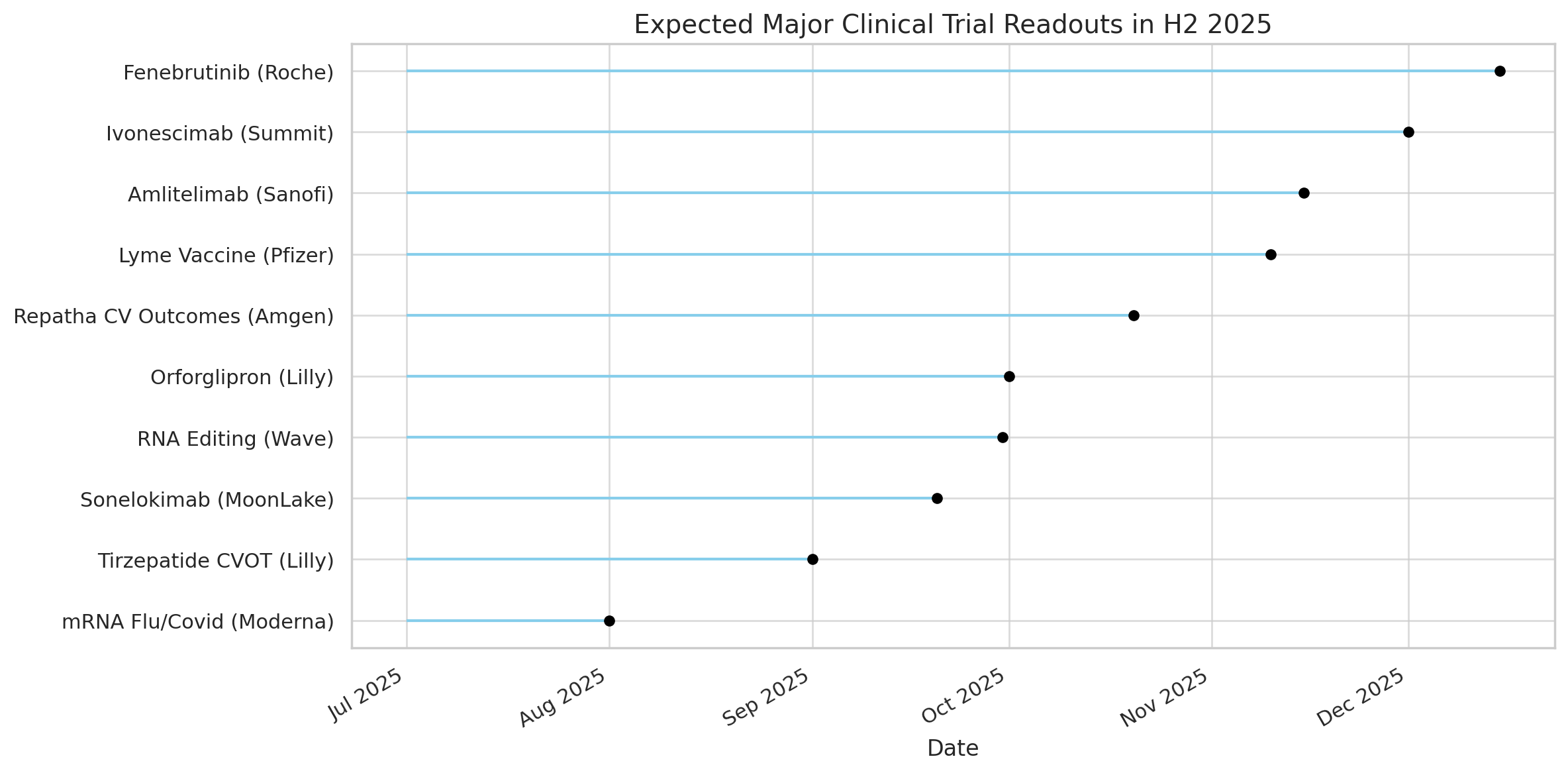

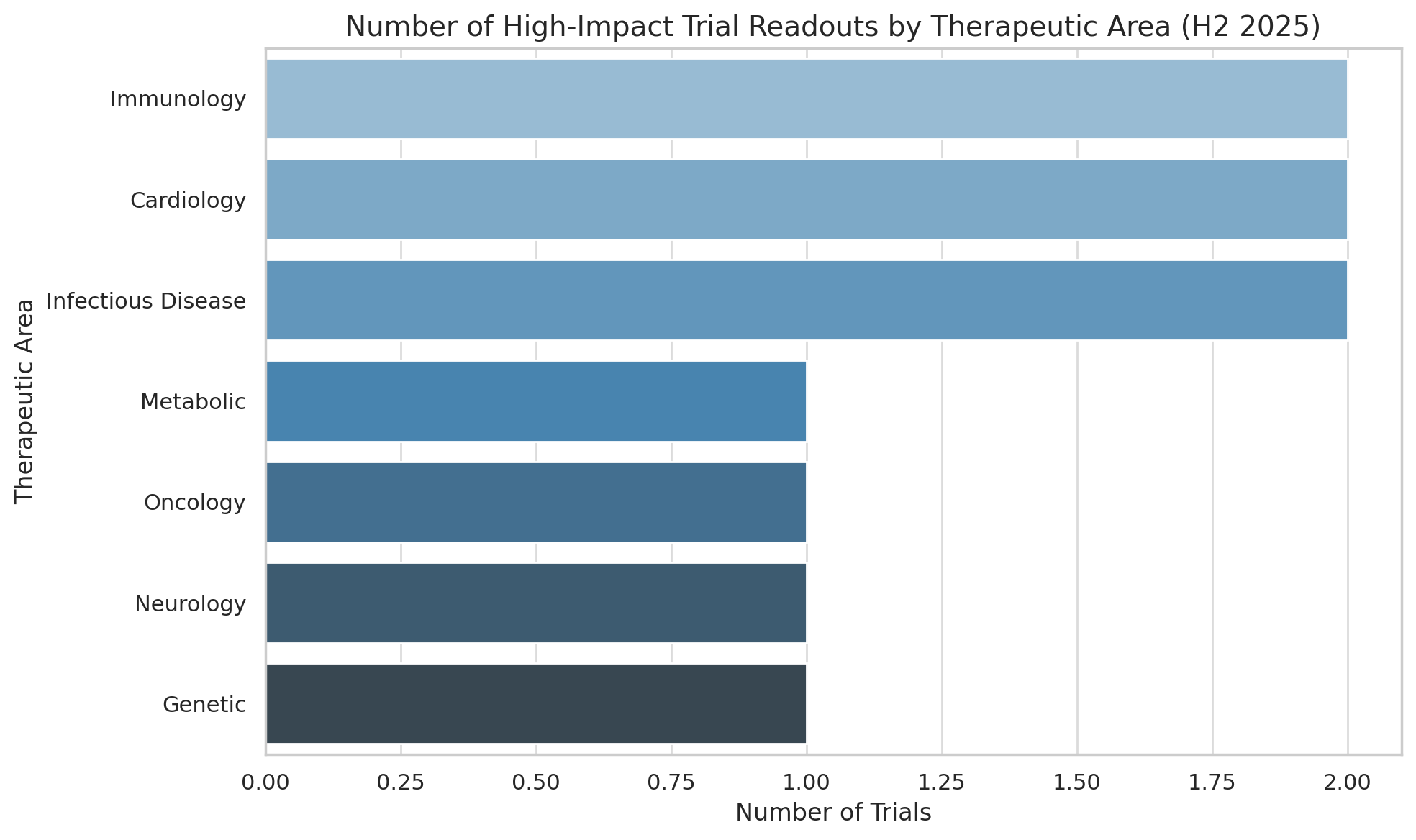

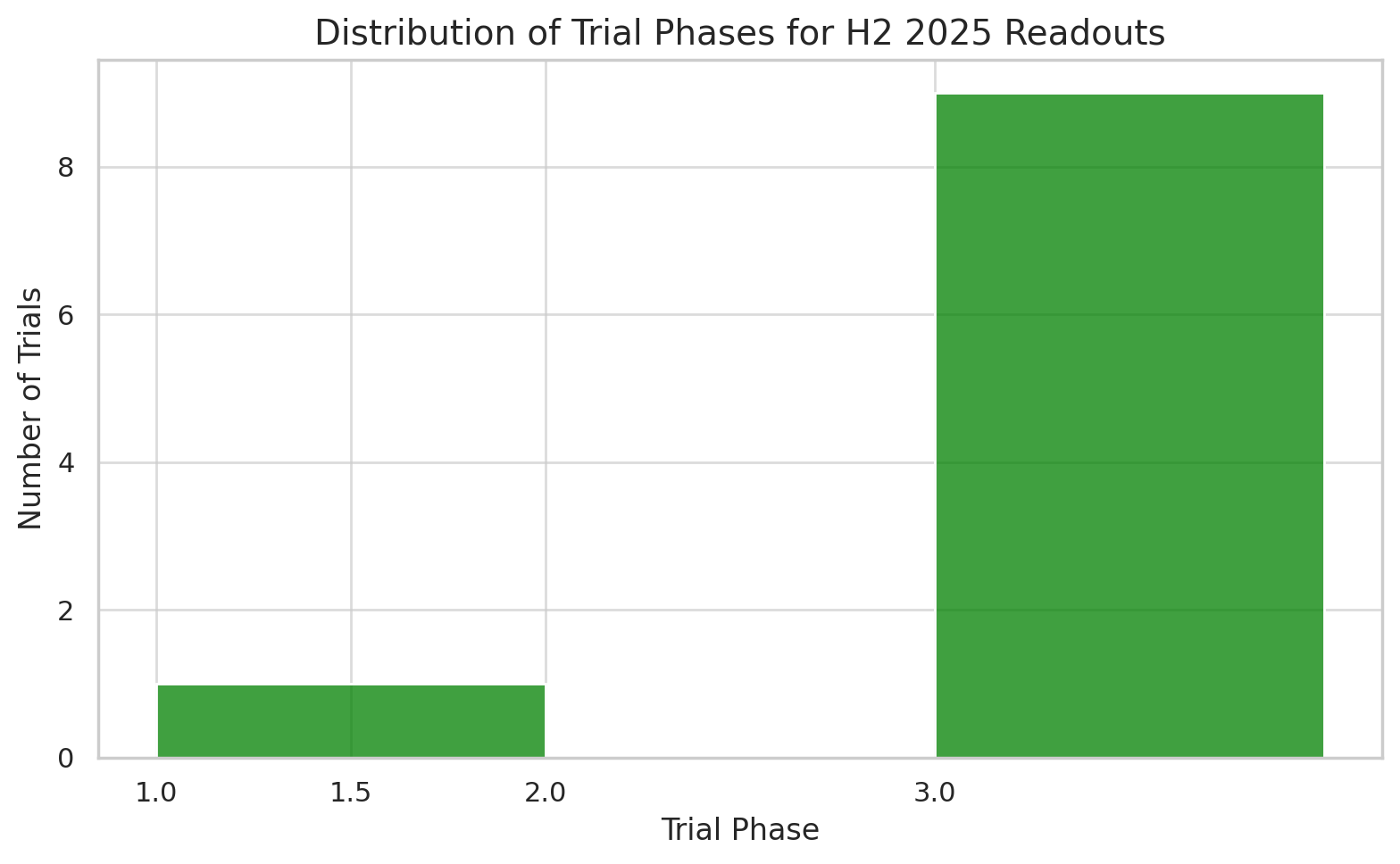

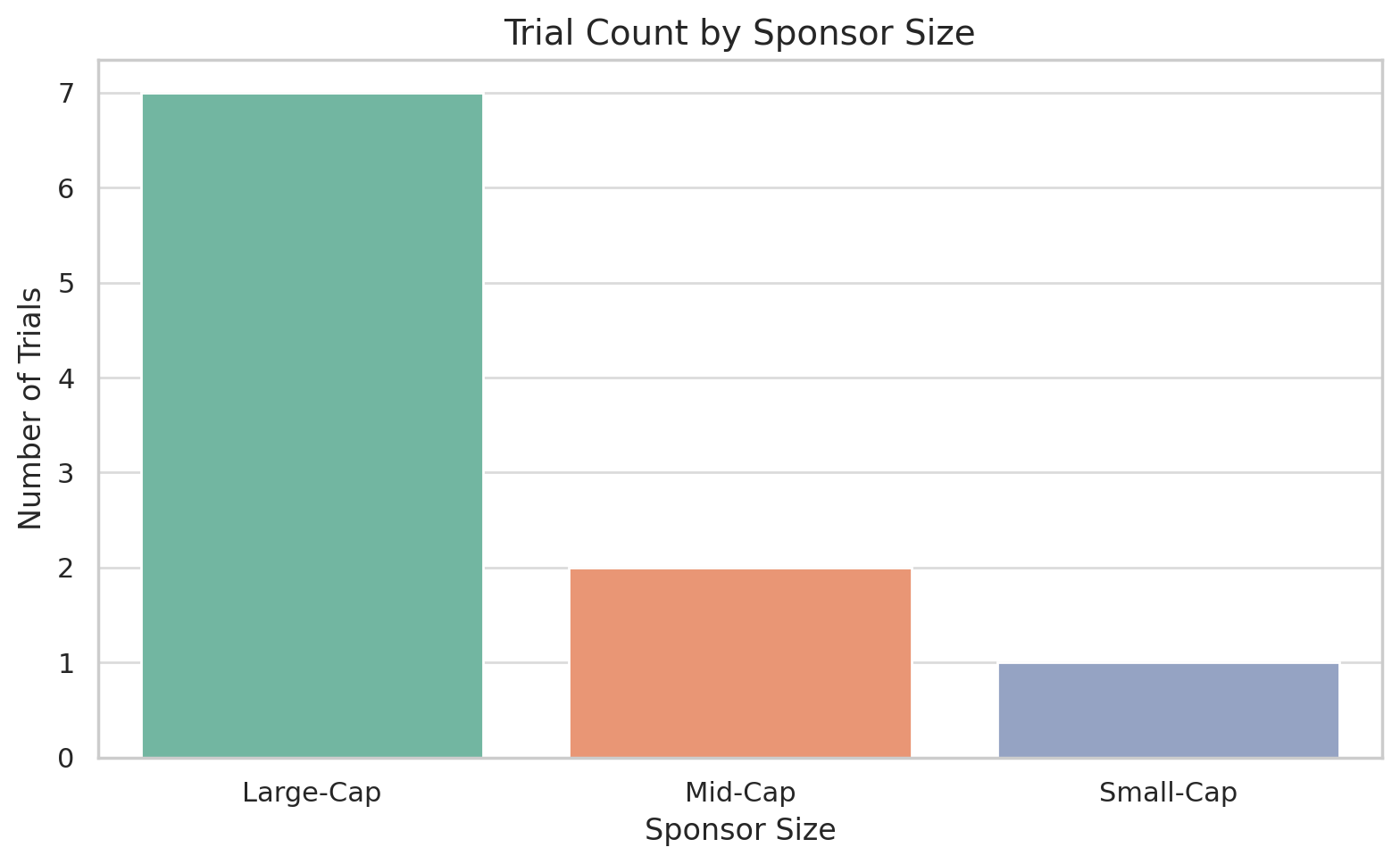

The second half of 2025 is poised to deliver a wave of critical clinical trial readouts across the biopharmaceutical industry. From potential blockbuster obesity drugs to cutting-edge gene therapies and vaccines, dozens of late-stage studies around the world will report data that could reshape treatment paradigms and financial fortunes. Investors and business development teams are watching these trials closely, as their outcomes will influence regulatory approvals, partnership opportunities, and the competitive landscape in multiple therapy areas.

Below we highlight some of the most anticipated trial results expected in H2 2025, along with key statistics and context for each:

Orforglipron (Eli Lilly)

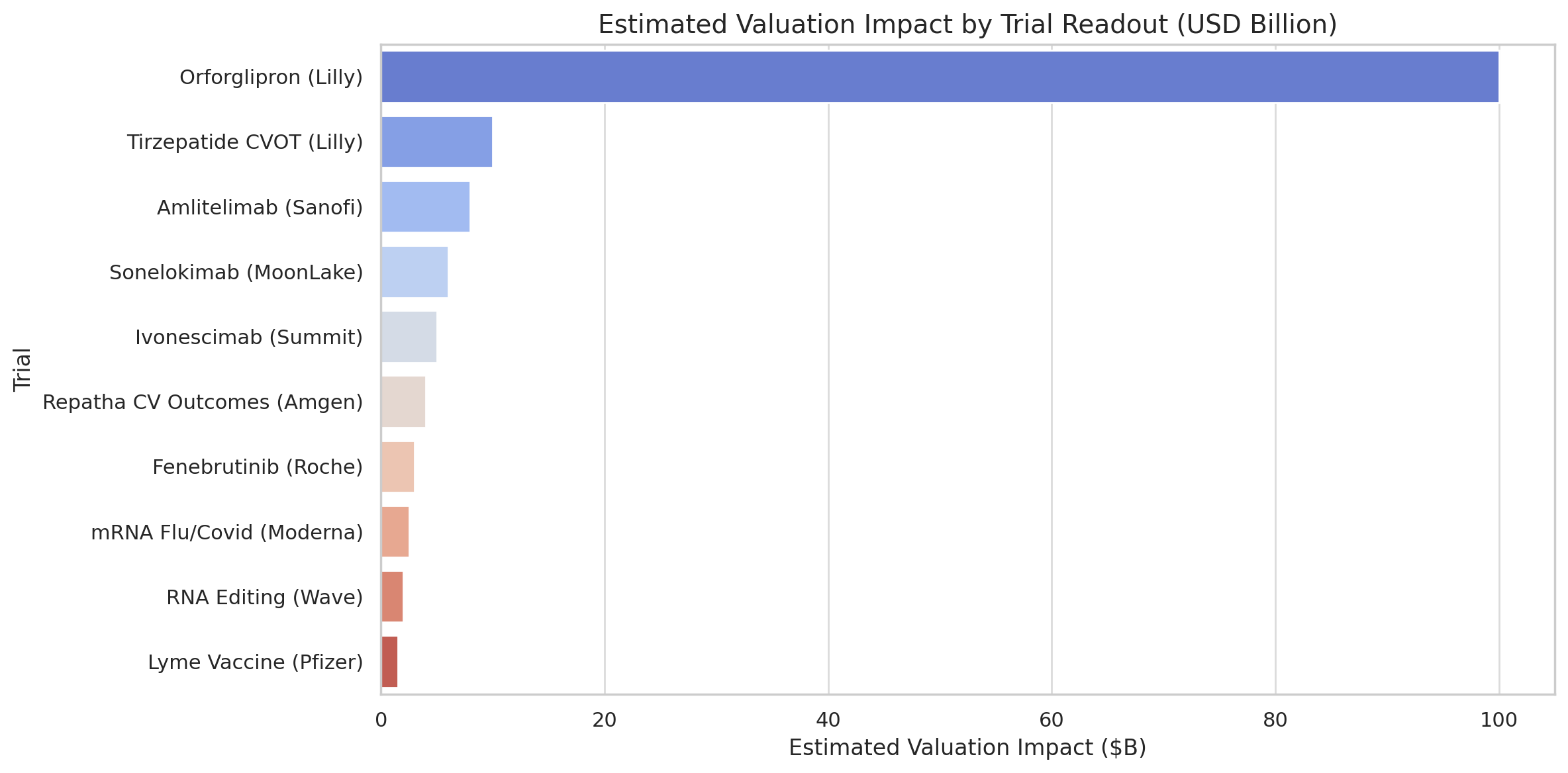

First-in-class oral GLP-1 agonist (small molecule) for obesity. A Phase 3 obesity trial is due to read out, following striking earlier data in diabetes that briefly added ~$100 billion to Lilly’s market cap. Over 13,000 patients are enrolled across trials, and success could unlock a mass-market, easily-manufactured weight-loss pill (biopharmadive.com).

Amlitelimab (Sanofi)

Novel anti-OX40L antibody for inflammatory diseases (e.g. eczema). Two Phase 3 trials (Coast-1, Coast-2) in atopic dermatitis could yield early results by late 2025. Sanofi projects >€5 billion in annual peak sales if successful (analysts peg >$8 billion), as it aims to follow up on its $14 billion blockbuster Dupixent (biopharmadive.com).

Sonelokimab (MoonLake)

IL-17 cytokine inhibitor antibody in Phase 3 for hidradenitis suppurativa (a severe skin disease), with twin trials (VELA-1,2) finishing in September (biopharmadive.com). MoonLake rejected a Merck buyout offer, signaling high expectations. Executives are targeting a ≥20% placebo delta on response rates, aiming to beat Humira and newer IL-17 drugs in this underserved market.

Ivonescimab (Summit/Akeso)

First-in-class PD-1/VEGF bispecific antibody for lung cancer. Phase 3 data (Harmoni-2 trial) expected around end of 2025biopharmadive.com will reveal if it improves survival over Keytruda after earlier results halved progression risk. Already approved in China, it’s the vanguard of ~12 similar dual-checkpoint drugs in development. Outcome could validate or undermine billions in licensing deals across pharma (biopharmadive.com).

Fenebrutinib (Roche)

Oral BTK inhibitor for multiple sclerosis, with three Phase 3 trials (two in relapsing MS, one in primary progressive) slated to report by Q4 2025. Over 2,700 patients have participated in Roche’s fenebrutinib program (roche.com). Rivals from Sanofi and Merck KGaA failed earlier, so these results will test whether Roche’s reversible BTK blocker can succeed where others fell short.

RNA Editing therapy (Wave Life Sciences)

An experimental RNA base-editing oligonucleotide for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). After two patients given a single dose showed a dramatic rise in the missing A1AT protein with no serious adverse events, a multi-dose Phase 1/2 readout in Q3 2025 will indicate if repeat dosing boosts efficacy without new safety issues This is a proof-of-concept for the RNA editing field being pursued by ~a dozen companies (biopharmadive.com).

Repatha “Vesalius” Outcomes (Amgen)

A primary prevention cardiovascular outcomes trial (VESALIUS-CV) testing the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in ~13,000 patients who haven’t yet had a cardiac event. Results due in H2 2025 will show if aggressive LDL-lowering prevents first heart attacks/strokes. A positive outcome could vastly expand Repatha’s use (tens of millions more patients globally) and sustain its $2.2 billion/year sales growth into 2030 despite upcoming competition (biopharmadive.com).

Lyme Disease Vaccine (Pfizer/Valneva)

A Phase 3 trial (~12,000 participants) of VLA15, the only advanced Lyme vaccine, will read out in late 2025. After a trial restart and expansion (due to site misconduct), success could lead to the first Lyme vaccine in 25 years, tapping an estimated >$1 billion annual market amid ~500,000 yearly US cases. Valneva stands to gain up to $143 million in milestones plus royalties if approved (biopharmadive.com).

“Flu-Covid” mRNA Vaccines (Moderna)

Efficacy data on Moderna’s mRNA-1010 flu vaccine (Phase 3) is expected by summer 2025, a gating factor for its high-priority combined Flu/Covid shot. Moderna already touted positive immunogenicity data, but stricter FDA standards forced it to delay filings. With COVID vaccine sales plunging >90% from 2021 highs, the combo vaccine (mRNA-1083) is seen as critical for Moderna’s post-pandemic profitability (biopharmadive.com).

Tirzepatide CV Outcomes (Eli Lilly)

The Surpass-CVOT study in 13,000+ diabetics will reveal whether Lilly’s GLP-1 agonist (Mounjaro/Zepbound) cuts cardiovascular events versus an active comparator (Trulicity). Results are expected by Q3 2025. Novo Nordisk’s rival Wegovy showed a 20% reduction in heart risk in 2023, helping unlock broader reimbursement. Lilly’s trial has a higher bar – going head-to-head against another heart-friendly drug – and could solidify tirzepatide’s profile ahead of a 2027 obesity outcomes trial (biopharmadive.com).

These are just a few of the headline events in what promises to be an extraordinarily busy late 2025 for clinical development. In the sections below, we delve deeper into these and other notable trials across major therapeutic areas – from metabolic diseases and cardiology, to immunology, oncology, neurology, and rare genetic disorders – providing context on their significance, relevant statistics, and potential market impact.

The goal is to blend an investor’s perspective on commercial implications with The Economist’s global, big-picture view of scientific and medical progress. Short, data-rich analyses will highlight why each readout matters and what to watch for as results emerge.

Metabolic & Cardiovascular: Weight-Loss Revolution and Heart Outcomes

Few areas in biopharma are as white-hot as metabolic disease. Treatments for obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk are generating staggering sales and stock market valuations. In H2 2025, that momentum will be tested by several high-profile trial results that could expand these drugs’ reach even further – or expose limitations that temper the enthusiasm. Investors have honed in on these readouts given the enormous patient populations and revenues at stake.

Lilly’s Oral Obesity Pill – Orforglipron (Attain Trials)

One of the most anticipated results is for Eli Lilly’s orforglipron, which could become the first oral GLP-1 receptor agonist for obesity. Unlike injectable peptides (e.g. semaglutide), orforglipron is a small molecule that can be mass-produced cheaply and taken as a pill (biopharmadive.com). Early signs are encouraging – Lilly stunned observers in April by disclosing striking Phase 3 data in type 2 diabetics (a population that typically loses less weight than non-diabetics).

Although that 40-week diabetes study was relatively short, the efficacy was robust enough that Lilly’s market capitalization jumped by about $100 billion after the announcement. This raised hopes that longer trials in obesity (the “Attain” studies) could show even greater weight loss in non-diabetic patients (biopharmadive.com).

However, detailed data published in June 2025 tempered some of the excitement. The results, presented at a scientific meeting and in The New England Journal of Medicine, revealed a plateauing of weight loss over time and persistent gastrointestinal side effects (a known class issue for GLP-1 drugs) In fact, a significant number of patients experienced severe or frequent nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, which could limit tolerability (biopharmadive.com).

“We are less bullish about the prospects of orforglipron in obesity,” concluded one analyst, noting the GI profile (biopharmadive.com). This illustrates the key question going into the obesity readout: can orforglipron’s convenience (a daily pill) compensate for potentially greater side effects or slightly lower efficacy than injectable therapy? Lilly’s management emphasizes that as a non-peptide, orforglipron may still be a game-changer by allowing millions of patients to access obesity treatment without injections.

The Phase 3 obesity trials due later in 2025 will be closely scrutinized for: total weight reduction (% of body weight lost), durability of effect beyond 40 weeks, and dropout rates due to tolerability. A positive outcome could position orforglipron as a blockbuster that helps Lilly extend its domination in metabolic diseases (where its injectable tirzepatide already generates >$1 billion quarterly). On the flip side, any safety or efficacy shortfall might give competitors (like Pfizer’s oral GLP-1 in development) an opening.

Cardiovascular Outcomes of GLP-1 Drugs – Tirzepatide’s Surpass-CVOT

The GLP-1 class is also being evaluated for hard cardiovascular outcomes, beyond weight and glucose control. In mid-2023, Novo Nordisk’s SELECT trial proved that Wegovy (semaglutide) can cut heart attacks, strokes, and cardiovascular deaths by 20% in overweight patients (biopharmadive.com).

This landmark finding not only bolstered the clinical credibility of obesity drugs but also prompted insurers to broaden coverage for Wegovy. Next up is Lilly’s Surpass-CVOT, slated to read out by the third quarter of 2025. This trial has enrolled over 13,000 patients with type 2 diabetes, all of whom have high cardiovascular risk (biopharmadive.com).

Uniquely, it pits Lilly’s GLP-1/GIP agonist tirzepatide (marketed as Mounjaro for diabetes and Zepbound for obesity) against active comparators – not placebo. Specifically, patients receive either tirzepatide or Lilly’s older GLP-1 drug Trulicity (dulaglutide), which itself has proven cardiovascular benefits.

This head-to-head design makes Surpass-CVOT both scientifically interesting and high-risk. Essentially, Lilly aims to show that tirzepatide is superior to an already-effective therapy in preventing major adverse cardiac events (MACE). If it succeeds, it would underscore tirzepatide’s status as perhaps the most potent incretin therapy on the market and could support even wider use (for example, persuading cardiologists to prefer it over competing GLP-1s).

Success would also bode well for Lilly’s obesity prevention trial (REDEFINE), which is testing tirzepatide in non-diabetic obese individuals for primary prevention of cardiovascular events. On the other hand, a negative or equivocal result – e.g. if tirzepatide only matches but does not beat Trulicity – could be seen as a setback.

It might imply a “class effect” ceiling for GLP-1 benefits and would be a blow to Lilly’s differentiation strategy vis-à-vis Novo. Investors will be looking at the hazard ratio for MACE, the statistical significance, and any signals in subpopulations. Given that Trulicity already reduces CV events by ~12%, demonstrating added benefit on top of that will require tirzepatide to meaningfully outperform a high bar. Regardless of outcome, this trial is important in cementing incretin-based drugs not only as metabolic agents but as cardioprotective medications – potentially expanding insurance reimbursement and guidelines to reflect their dual role.

Reimagining Heart Disease Prevention – Amgen’s Repatha in Primary Prevention: In the cardiovascular arena, another closely watched study is Amgen’s Vesalius-CV trial of Repatha (evolocumab). Repatha, a PCSK9 inhibitor antibody, is already approved and widely used for lowering LDL cholesterol in patients with established atherosclerotic disease. The drug has shown a clear benefit in secondary prevention – for patients who have already suffered a heart attack or stroke – with global sales topping $2.2 billion in 2022.

However, its uptake was initially slow, and payers were skeptical of its value, leading to underestimation of the market. Today, those barriers have eased and Repatha’s growth has accelerated.

The big question now: can PCSK9 inhibitors move “one step earlier” in the care paradigm, preventing first cardiovascular events in high-risk yet apparently healthy individuals? That’s what Vesalius-CV is testing – using Repatha as a first-line preventive therapy in patients with risk factors but no prior heart attack or stroke (biopharmadive.com).

The trial’s outcome, expected in late 2025, carries significant commercial implications. As Leerink analysts noted, a positive readout could “drive long-term Repatha growth” by expanding its label to a far larger primary prevention population. The addressable group is huge: despite statins and other drugs, tens of millions globally still have uncontrolled cholesterol levels and heightened risk. Current penetration of PCSK9 drugs in eligible patients remains very low, partly due to historical cost and access issues.

If Repatha is shown to decisively prevent initial cardiac events, it could persuade guidelines and payers to support much broader use – potentially turning Repatha into the kind of mass-market cardiovascular drug that statins became in earlier decades. Even with competition looming (e.g. Merck’s oral PCSK9 inhibitor, which succeeded in Phase 3), Amgen’s management is optimistic that expanding the pie will benefit Repatha without derailing its trajectory.

After all, cardiovascular prevention is not a zero-sum game; as Amgen’s commercial head put it, “there is room for competition” given the vast unmet need. Investors will watch for the magnitude of risk reduction in Vesalius (for example, a hazard ratio similar to prior statin trials in primary prevention) and safety/tolerability signals from long-term potent LDL suppression.

A compelling benefit could make Repatha a multi-billion dollar franchise through the end of the decade, just before its patents expire around 2029 (biopharmadive.com).

Targeting Lp(a) – Novartis’s Landmark Pelacarsen Study Delayed

While LDL cholesterol has been the main focus for decades, another cardiovascular risk factor – lipoprotein(a) – is finally getting its moment in the spotlight. Novartis’s pelacarsen (an antisense oligonucleotide) is designed to reduce Lp(a), an inherited cholesterol particle implicated in heart disease. The company’s Lp(a)Horizon trial (started in 2019 with >8,000 patients) is the first major test of whether lowering Lp(a) translates into fewer cardiovascular events (biopharmadive.com).

As of mid-2025, Lp(a)Horizon is in its endgame, but Novartis signaled that the trial – which is event-driven – likely won’t report until 2026, slightly later than originally hoped. Nonetheless, it’s worth mentioning in an outlook for late 2025 because any hint of interim data or progress will be closely followed by analysts. If positive, pelacarsen could be a first-in-class therapy unlocking multibillion-dollar sales and validating Lp(a) as the “third leg” of lipid management (alongside LDL and triglycerides).

It would also vindicate the investments of others: Amgen and Lilly each have Lp(a)-lowering drugs in trials (biopharmadive.com), and success would “boost the confidence” that those follow-ons might also work. Conversely, a neutral outcome would be a disappointment that might cast doubt on the clinical relevance of Lp(a) despite strong genetic evidence. For now, Novartis has guided investors to be patient until next year, but the mere approach of the trial’s finish line has the cardiology community on alert.

In summary, metabolic and cardiovascular trials in H2 2025 could significantly broaden the uses of already hugely successful drug classes. We will see whether obesity therapeutics can achieve even greater heights in efficacy (or whether side effects constrain them), and whether their benefits extend to tangible improvements in heart health.

The results from Lilly’s and Novo’s programs, in particular, may influence billions in future sales and could even shift how primary care and specialty guidelines are written. In parallel, the push to address residual cardiovascular risk – through PCSK9 inhibition in wider populations or via novel targets like Lp(a) – continues, with outcomes that will determine if the industry’s big bets on these mechanisms pay off.

From an investment standpoint, these readouts carry high stakes: they will help differentiate winners and losers in the battle between two titans (Lilly vs. Novo in incretins, Amgen vs. Merck vs. Novartis in cardiometabolic drugs), all while potentially expanding the overall market if results are positive.

Immunology & Inflammatory Diseases: The Post-Dupixent Race

The success of Sanofi and Regeneron’s Dupixent (dupilumab), an IL-4/IL-13 blocker for allergic and inflammatory diseases, has ushered in a golden age for immunology drugs. With over $14 billion in 2024 sales and eight approved uses ranging from eczema to asthma, Dupixent has set a high bar – and also a looming patent cliff in the early 2030s (biopharmadive.com).

Big pharma is eager to find the “next Dupixent” to sustain growth in immunology. The latter half of 2025 will bring pivotal data for several contenders, each aiming to address unmet needs in prevalent inflammatory conditions (atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis, asthma, etc.) or to provide more convenient options.

Sanofi’s Amlitelimab – Broad-Spectrum Anti-OX40L

A major focus is on amlitelimab, Sanofi’s in-house challenger to Dupixent. Amlitelimab is a monoclonal antibody targeting OX40 ligand (OX40L), a co-stimulatory molecule that drives T-cell inflammation. By blocking OX40L, the drug is intended to calm overactive immune responses across a range of diseases. Sanofi acquired amlitelimab via its $1.45 billion buyout of Kymab in 2021 (biopharmadive.com).

Now the asset is in Phase 3 trials for atopic dermatitis (the “Coast-1” and “Coast-2” studies) as well as pivotal studies in other indications like asthma and hidradenitis suppurativa. Initially, Sanofi guided that primary readouts would come in 2026; however, faster-than-expected enrollment means an interim look or topline data from at least one study could emerge in H2 2025.

The company’s confidence is high – management has publicly stated amlitelimab could generate over €5 billion annually at peakbiopharmadive.com, potentially even eclipsing Dupixent’s success if it fulfills its multi-indication promise. Jefferies analysts are similarly bullish, modeling more than $8 billion in peak sales (biopharmadive.com).

Such lofty expectations hinge on eczema (atopic dermatitis) as the beachhead indication. There are millions of patients with moderate-to-severe eczema worldwide, and Dupixent (approved in 2017 for this use) has been transformative, yet ~50–60% of patients do not achieve clear skin and many remain uncontrolled. Amlitelimab’s Phase 2 data in eczema were encouraging: the drug showed “deep responses” in skin clearance in difficult-to-treat patients. Moreover, its mechanism is distinct from Dupixent’s IL-4/IL-13 blockade – OX40L is upstream in the inflammatory cascade – which could translate to broader immune modulation and possibly more durable remission.

Sanofi is positioning amlitelimab as a complementary, potentially longer-acting agent, perhaps even a first-line biologic for Dupixent non-responders in the future. There are, however, reasons for caution. Notably, Amgen recently had an OX40 ligand inhibitor (rocatinlimab) in development for eczema that failed to beat placebo in a Phase 3 trial, despite promising Phase 2 results.

That high-profile failure in early 2025 rattled investors and cast doubt on the OX40L pathway overall. Additionally, amlitelimab itself had a hiccup: it missed the efficacy endpoint in a mid-stage asthma trial (biopharmadive.com). Sanofi decided to push into Phase 3 for asthma regardless, arguing that their drug works differently from Amgen’s and that the totality of data in skin diseases remains strong.

All eyes will be on the efficacy delta vs placebo in the Coast eczema trials – specifically, metrics like the EASI-75 or IGA 0/1 response rates at 16 weeks. Dupilumab achieved ~44% IGA-clear in its trials; a significantly higher response or better durability by amlitelimab would underscore its value. Safety is another consideration: OX40L is expressed in lymphoid tissues, so watch for any T-cell related adverse events or signals of over-immunosuppression (though none prominent so far in trials).

If amlitelimab succeeds, it could validate Sanofi’s strategy of broad immunomodulation – the drug is being trialed in at least five indications concurrently – and solidify the company’s dominance in immunology into the next decade. For investors, success might confirm Sanofi’s status as a leader beyond Dupixent’s patent life, whereas failure could leave a big hole in the 2027+ pipeline outlook.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa Breakthrough – MoonLake’s Sonelokimab Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is another inflammatory condition drawing attention, and MoonLake Immunotherapeutics may be on the verge of a breakthrough. HS is a painful, chronic dermatological disease where recurrent abscesses and sinus tracts form in areas like the armpits and groin. It has been historically underdiagnosed and very difficult to treat.

Only a couple of biologics are approved (notably adalimumab/Humira and, more recently, infliximab biosimilars off-label; UCB’s IL-17 blocker Bimzelx was approved for HS in Europe in 2023). Efficacy of current options is modest at best, and dosing is frequent. MoonLake’s candidate sonelokimab is designed to address HS by simultaneously neutralizing two inflammatory cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F) and binding to albumin.

The latter feature (an albumin-binding domain) acts like a built-in shuttle, potentially increasing tissue penetration and drug half-life in inflamed skin. Sonelokimab’s small size relative to conventional antibodies might also allow it to better penetrate into lesions.

Two Phase 3 trials (VELA-1 and VELA-2) are expected to report topline results in September 2025. These studies will evaluate sonelokimab in moderate-to-severe HS patients, measuring the proportion achieving at least a 75% reduction in abscess and nodule count (HiSCR75) and other clinical endpoints. The company’s leadership has indicated they are hoping to see a placebo-adjusted response delta of ≥20% on HiSCR75 – that is, a meaningful improvement over the roughly ~45% placebo response often seen in HS studies. Achieving that would be “clinically meaningful and competitive” relative to existing biologics.

For context, in Phase 2, sonelokimab did show a strong efficacy signal, but the dose-response was not perfectly clear (higher doses didn’t dramatically outperform lower ones), which raised some investor skepticism. Nonetheless, the total data package so far led analysts at SVB Leerink to describe an “optimal profile” with strong efficacy and encouraging safety compared to IL-17A inhibitors like secukinumab.

The stakes are high for MoonLake, a smaller biotech headquartered in Switzerland. In fact, big pharma is already circling: earlier in 2025, Merck & Co. reportedly made a buyout offer for MoonLake in the range of $6 billion, which the company turned down. That suggests MoonLake’s management is confident in sonelokimab’s prospects. Analysts concur that if the Phase 3 mirrors Phase 2 performance, sonelokimab could become a blockbuster (>$1 billion/year drug) in HS.

Cantor Fitzgerald projected that even if the drug is essentially a “me-too” to UCB’s IL-17F inhibitor (Bimzelx), the sheer unmet need in HS means it’s “likely to be a blockbuster”m. Moreover, sonelokimab’s potentially less frequent dosing (thanks to the albumin-binding tech) could differentiate it in convenience.

Key data points to watch from VELA-1 and 2 include: the percentage of patients hitting HiSCR50 and 75 (higher is better), durability of response over the 6-month trial, and any reduction in draining fistulas (a particularly debilitating aspect of HS). Safety will be important too; IL-17 blockade can cause Candida infections and rarely neutropenia, but no major red flags have appeared so far. If successful, MoonLake could file for approval in 2026, racing Bimzelx for the U.S. market in HS. A positive readout might also rejuvenate interest in multi-cytokine targeting strategies for other diseases.

On the flip side, a failure would not only hit MoonLake’s stock hard but might also validate doubts about the IL-17 pathway’s consistency in HS. Given the underlying market size – HS may affect up to 1% of adults (though severe cases are a subset) – the outcome will influence how much pharmaceutical companies invest in this area going forward. For patients, a new effective therapy can’t come soon enough, as HS dramatically impacts quality of life and currently has limited options.

Oral Alternatives for Autoimmune Diseases – The Integrin Inhibitor MORF-057 (Lilly)

While not reading out until early 2026, it is worth noting the Emerald-2 trial for Morphic Therapeutic’s oral integrin antagonist (MORF-057) in ulcerative colitis, because it highlights a broader trend in immunology: the push toward convenient oral therapies. In mid-2025, Eli Lilly acquired Morphic for $3.2 billion, betting that MORF-057 could achieve similar efficacy to Takeda’s injectable Entyvio (vedolizumab) but as a pill. Interim data had suggested it might be roughly as effective as Entyvio in uncontrolled ulcerative colitis.

The full placebo-controlled Phase 2 (Emerald-2) will be a crucial proof point in 2026, and a positive result could validate a shift wherein chronic inflammatory conditions increasingly move from injections/infusions to oral medications.

This is analogous to what happened in rheumatoid arthritis years ago with JAK inhibitors complementing anti-TNF injections. For IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) and others, we see similar momentum: Pfizer and BMS are developing oral agents (like TYK2 inhibitors, etc.).

So while Emerald-2’s readout is beyond H2 2025, its setup – fueled by a big-ticket acquisition – underscores how investors and pharma are positioning for more patient-friendly immunology treatments. If Lilly’s gamble pays off (analysts think MORF-057 could surpass $2 billion/year if approved), it will reinforce that trend, whereas a miss would remind that biologics still reign supreme for efficacy.

In summary, the latter half of 2025 should significantly advance the immunology field’s next generation of therapies. We will learn whether Sanofi can extend its immunology franchise beyond Dupixent with a novel target (OX40L) – or if recent competitor failures indicate a fundamental challenge.

We’ll also see if MoonLake’s ambitious bet in HS yields the first major win for that debilitating disease. And across the board, the data will inform how aggressively companies pursue novel mechanisms and modalities (bi-specific antibodies, oral small molecules, etc.) to address immune-driven illnesses. The commercial implications are huge: these diseases (eczema, asthma, HS, IBD, psoriasis, lupus, and more) collectively represent tens of billions in drug sales. Every percentage point improvement in remission rates or each convenience edge can translate to sizable shifts in market share.

For investors, success for amlitelimab or sonelokimab would likely trigger M&A or partnership interest (especially with MoonLake as a mid-cap) and support valuations of peers in the same pathway (e.g. other OX40, IL-17, or TNF-family targeting companies). Failure, conversely, could depress the segment and send companies back to the drawing board for new angles.

Oncology: New Frontiers in Cancer Therapy and High-Stakes Trials

Oncology drug development continues at a torrid pace in 2025, with hundreds of trials ongoing. While many cancer trials are early-stage or incremental, a few late-stage readouts in H2 2025 stand out for their potential to shift standards of care or validate novel therapeutic approaches. This year’s oncology catalysts range from innovative immunotherapies (bispecific antibodies, protein degraders) to confirmatory trials of targeted agents. The outcomes will not only impact patients and physicians but also could move biotech stock prices dramatically – hence the “biotech catalyst calendars” closely track several of these events.

PD-1 + VEGF Bispecific – Akeso/Summit’s Ivonescimab (SMT112)

Perhaps the most closely watched oncology readout is for ivonescimab, a unique antibody that blocks two pathways at once: PD-1 and VEGF. This “two-in-one” approach aims to improve upon the established success of PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors (like Merck’s Keytruda) by concurrently inhibiting VEGF, thereby cutting off tumors’ blood supply and modifying the tumor microenvironment.

The concept is compelling because Keytruda and other PD-(L)1 drugs are the backbone of treatment in dozens of cancers, so a superior agent could rapidly gain widespread use. Early evidence for ivonescimab caused a sensation: in 2024, Akeso (the drug’s originator in China) reported a Phase 3 trial in non-small cell lung cancer where ivonescimab plus chemo outperformed Keytruda plus chemo in progression-free survival.

This was the first time any therapy had beaten Keytruda in a head-to-head trial for first-line lung cancer, and it stunned oncology researchers. Summit Therapeutics obtained rights to ivonescimab outside Asia through a $5 billion licensing deal, underscoring the excitement.

However, subsequent data introduced some caution. Additional analyses of that same study (known as Harmoni-3 in China) showed that at an interim look, ivonescimab did not yet improve overall survival (OS) compared to Keytruda. The hazard ratio for OS was not statistically significant, disappointing investors and raising questions about whether the PFS benefit would translate into a survival advantage.

It’s not uncommon in oncology for early PFS gains to narrow or disappear over time (especially if cross-over therapy is allowed), and analysts have pointed out a “rule of thumb” that interim positive results often “degrade over time” in cancer trials. Akeso has indicated that a final OS analysis from the Harmoni-2 study (a global trial in a similar setting) is expected around end of 2025.

This is the key readout: if ivonescimab ultimately shows a statistically significant OS benefit over Keytruda, it would validate the PD-1/VEGF bispecific strategy and likely intensify efforts by others in this class. Notably, ivonescimab is just the frontrunner among at least a dozen PD-1-based bispecifics in development; major firms like Roche, Pfizer, and J&J have either in-house programs or deals for similar molecules.

Some have already placed bets – for example, in April 2025, China’s regulator approved ivonescimab for lung cancer based on the PFS data, which triggered a clause for an early OS peek as discussed. Other companies will benefit (or suffer) from ivonescimab’s fate: a clear win could spur licensing deals and raise valuations of those in the same arena, whereas a failure to improve survival might lead to skepticism and perhaps abandonment of several copycat projects.

From a commercial perspective, if ivonescimab fulfills its promise, it could become a megablockbuster. Keytruda itself is tracking toward ~$30 billion in annual sales by 2025 across indications. A drug that meaningfully outperforms Keytruda in major cancers like lung would capture a large slice of that pie (even if priced at a premium). Summit Therapeutics would be in a position to file for approvals in the US/EU, and one can imagine large pharma partners (or acquirers) lining up, given Summit’s relatively small size.

Conversely, should OS remain flat, the narrative may become “ivonescimab wins on PFS but not OS, so is it really better?” – which would complicate uptake and could mark the approach as more hype than substance. Therefore, investors will scrutinize the hazard ratio for OS, the confidence intervals, and whether any subgroups (e.g. high PD-L1 expressors vs low) derive particular benefit.

It’s worth noting that even if OS is negative, companies might argue that a PFS benefit with half the progression risk (the China trial showed about 50% reduction) is clinically meaningful to patients, especially if coupled with any quality-of-life or brain metastasis benefits. But regulators and payers typically hold OS as the gold standard in front-line cancer settings.

A New Class of Cancer Medicine – Targeted Protein Degraders (Arvinas’s Vepdegestrant)

Over the past few years, targeted protein degradation has emerged as a cutting-edge drug modality. Rather than inhibiting a protein’s function, degraders (often called PROTACs) tag disease-causing proteins for destruction by the cell’s own garbage disposal system. Arvinas, a pioneer in this field, reached a milestone in 2025 with the first Phase 3 trial of a PROTAC. The molecule, vepdegestrant (ARV-471), is an oral degrader of the estrogen receptor (ER) being tested in ER-positive breast cancer.

In Q1 2025, Arvinas and its partner Pfizer read out the VERITAC-2 trial, comparing vepdegestrant to fulvestrant (the standard ER-blocker) in metastatic breast cancer. Full data were presented in June 2025. This was a pivotal moment for the field: a win would have signaled that protein degraders can beat existing therapies in a large indication, potentially opening the floodgates for other programs (Arvinas themselves have multiple partnerships and other trials).

As it turned out, vepdegestrant did not clearly outperform fulvestrant in this first trial – it missed demonstrating a significant improvement in progression-free survival (per investor reports). This adds pressure on the remaining Phase 3s in 2025/2026 to show some benefit. The landscape evolved in the interim: another oral ER degrader from AstraZeneca (not a PROTAC, but a different chemical class) was approved in 2023, and Lilly has one in late-stage trials. These successes raised the efficacy bar.

Arvinas’s experience highlights how early hype can collide with clinical reality. Investors initially valued Arvinas in the billions on the PROTAC promise, but skepticism grew as the competitive environment stiffened. By late 2025, it’s clear that while targeted degradation is scientifically exciting and works intracellularly, demonstrating meaningful clinical advantages is challenging. Nonetheless, Arvinas’s journey (win, lose, or draw) is instructive. It shows big pharmas are willing to bet on new mechanisms (Pfizer’s multi-billion dollar partnership with Arvinas) and how quick the field is to pivot – for example, Arvinas already has next-generation ER degraders and other targets in the works, aiming for differentiation beyond just “me-too” of fulvestrant.

For the broader industry, a lingering question is whether degrader technology will deliver on its promise across oncology (targets like KRAS, Myc, and others are being pursued). The verdict from vepdegestrant’s pivotal trials, plus other ongoing Phase 2s (e.g. FAK degraders, androgen receptor degraders), will shape the future of this approach.

While not a singular H2 2025 event (Arvinas’s key data dropped earlier in the year), the follow-up in late 2025 will involve how the company and Pfizer proceed – will they file for a narrow subgroup? Will they discontinue or double-down? Those decisions, influenced by the data, are of great interest to investors in next-gen oncology platforms.

A New Standard in Lung Cancer – Amgen’s Tarlatamab (BiTE for SCLC)

Among immunotherapies, T-cell engagers are gaining traction. Amgen’s tarlatamab is a BiTE (bispecific T cell engager) antibody that directs T cells to attack cancer cells expressing DLL3, a protein prevalent in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). SCLC is a notoriously aggressive cancer with limited second-line options – most patients relapse after chemotherapy and have a grim prognosis. Tarlatamab showed promising response rates in early trials, and on the strength of Phase 2 results, the FDA granted it accelerated approval in late 2024 for relapsed SCLC (nature.com).

The confirmatory Phase 3 trial (DeLLphi-304), which reported interim data in mid-2025, demonstrated that tarlatamab significantly improves overall survival compared to standard chemotherapy in second-line SCLC. Specifically, 509 patients were randomized to tarlatamab vs chemo, and the BiTE therapy reduced the risk of death by roughly 40% versus the control arm, marking the first major advance in SCLC treatment in years (dailynews.ascopubs.org). These findings were published in NEJM in 2025 and have been hailed as practice-changing.

For Amgen, this is a vindication of their BiTE platform (which previously produced Blincyto for leukemia). It also opens a new franchise: if approved globally, tarlatamab could become the standard second-line therapy in extensive-stage SCLC, a setting where currently only around 15% of patients respond to available drugs. Analysts predict substantial uptake given the lack of alternatives and the magnitude of benefit.

Beyond SCLC, the real excitement is whether BiTEs and similar off-the-shelf cell engager therapies can be extended to other solid tumors. DLL3 is also expressed in some neuroendocrine tumors, and other companies are exploring different targets (like PSMA in prostate cancer or BCMA in myeloma) with BiTEs. Tarlatamab’s success provides a proof-point that bispecific immune engagers can work in solid tumors, which historically have been challenging for cellular immunotherapies (like CAR-T cells).

It’s also worth noting that tarlatamab achieved these results as a monotherapy in a very tough cancer – this bodes well for trying combinations (adding checkpoint inhibitors or other agents) to possibly move BiTEs to front-line therapy eventually.

From a market perspective, Amgen’s tarlatamab could generate several hundred million in annual sales in SCLC and help the company diversify its oncology portfolio. It additionally pressures competitors working on DLL3 (there are a few CAR-T and antibody-drug conjugate approaches in development – those will now have to compare to tarlatamab’s efficacy).

For biotech investors, this win has boosted confidence in companies developing T-cell engagers (e.g., smaller biotechs with bispecific platforms have seen renewed interest). It also reinforces Amgen’s strategy to focus on innovative biologics as its older drugs face biosimilars. In H2 2025, one likely event is a regulatory decision or expanded data presentation for tarlatamab – while the pivotal data is known, the formal approval and labeling (which could come in late 2025 or early 2026) will determine exactly how broadly it can be used (e.g., which line of therapy, any biomarker restrictions, etc.). This, in turn, influences revenue forecasts.

Other Oncology Catalysts and Trends

There are numerous other cancer trials reading out in late 2025, albeit many are more niche or earlier stage. A few worth mentioning include:

Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors

Iovance Biotherapeutics has been developing tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy for advanced melanoma (lifileucel). After some regulatory delays, the company is expecting an FDA decision by 2025. If approved, it would be the first TIL therapy on the market, offering a new option for melanoma patients who fail checkpoints. This isn’t a single trial readout per se, but it’s a moment that could spur interest in cell therapies for solid tumors – a space that has seen setbacks (like CAR-Ts failing in solid tumors) but still holds promise with approaches like TILs, CAR-NK cells, etc.

For business development professionals, an approval could make Iovance an attractive partner or acquisition target for a larger oncology player seeking cell therapy expertise.

Cancer Vaccines & Neoantigen Therapies

While most pivotal cancer vaccine trials (e.g. Moderna/Merck’s personalized mRNA vaccine in melanoma, BioNTech’s programs) are expected in 2026–2027, late 2025 will see data updates from ongoing studies. For example, BioNTech may reveal interim data from its Phase 2 in colorectal cancer (autogene cevumeran) or final data from a Phase 2 in melanoma with its FixVac off-the-shelf vaccine (genengnews.com). The cancer vaccine field, after decades of failure, has new optimism thanks to positive signals in 2022–2023 (Moderna’s small Phase 2 being a prime example). So any data in 2H 2025 – even if interim – will be parsed for signs that these vaccines are hitting clinical endpoints.

A notable one is BioNTech’s BNT111 trial in PD1-refractory melanoma, where data could drop in late 2025. If encouraging, it could further validate the concept of using vaccines to boost immune response in cancer, and might ignite investment or partnerships (already we saw deals like GSK’s tie-up with CureVac on mRNA cancer vaccines, etc.). The Economist-style view here is that scientific persistence may be paying off – after “decades of failure” the field finally has concrete successes, and now more and more late-stage data is coming. The late 2025 findings will either add to that momentum or remind us that each vaccine is unique and some may not pan out.

Next-Gen Targeted Therapies

The relentless hunt for better targeted drugs continues. In lung cancer, we anticipate final overall survival data from trials like ADAURA (Osimertinib in early-stage EGFR-mutant lung cancer) and CodeBreaK-300 (combining Amgen’s KRAS inhibitor sotorasib with chemotherapy in 1L lung). ADAURA’s disease-free survival data was so positive it already changed practice; OS data (if positive in late 2025) would cement adjuvant osimertinib as standard of care.

For KRAS inhibitors, a positive combo trial could expand usage to earlier lines (beyond the current 2nd line approvals for KRAS G12C inhibitors). Additionally, in breast cancer, data from trials of Enhertu (a HER2 ADC) in low-HER2 breast cancer or Lynparza plus AI in adjuvant breast cancer might emerge by late 2025, potentially broadening labels for those drugs. Each of these results can have multi-hundred-million-dollar implications for the companies involved (e.g., AstraZeneca/Daiichi Sankyo for Enhertu, AstraZeneca/Merck for Lynparza).

To sum up, the oncology catalyst slate for H2 2025 reflects both validation of new modalities and fierce battles in existing classes. We expect clarity on whether bispecific antibodies can unseat today’s oncology blockbusters, whether protein degraders can join the oncology arsenal, and how immunotherapies like T-cell engagers and vaccines are evolving.

For investors, oncology remains a high-risk, high-reward area – trial successes can send stocks soaring (or trigger lucrative buyouts), while failures often crater valuations. One advantage in oncology is that markets are huge and even incremental benefits are rewarded, but conversely, competition is intense and payers are beginning to demand evidence of overall survival or clear patient benefit before paying for premium therapies (witness debates on costly PD-1 combos that only improve PFS). The late-2025 readouts we’ve discussed will contribute valuable evidence on these fronts, influencing everything from company pipelines to treatment guidelines globally.

Neurology & Psychiatry: Advances in Alzheimer’s, Depression, and Rare CNS Diseases

Central nervous system (CNS) disorders have historically been among the toughest areas for drug development, but recent breakthroughs – particularly in Alzheimer’s disease – have reinvigorated the field. The second half of 2025 will see important data in neurology and psychiatry, ranging from unconventional approaches to Alzheimer’s, to novel mechanisms for depression, to gene therapies for rare pediatric disorders. The outcomes could shape how we tackle these conditions and determine which companies lead the next wave of CNS innovations.

Can a Diabetes Drug Treat Alzheimer’s? – Novo Nordisk’s Semaglutide (oral) in Early Alzheimer’s (EVOKE trial)

One of the most intriguing trials of 2025 spans the intersection of metabolism and neurology. Novo Nordisk, known for its diabetes and obesity drugs, is testing whether semaglutide (the GLP-1 agonist) can slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The rationale stems from epidemiological links between diabetes and higher dementia risk, as well as early studies hinting that GLP-1 drugs might have neuroprotective effects.

Novo’s trial, named EVOKE, enrolled over 1,800 patients with early Alzheimer’s (mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia) and gave them high-dose oral semaglutide (the same molecule as in Ozempic pills for diabetes) for around 2 years. The primary endpoint is likely a change in cognitive score (e.g. CDR-SB or ADAS-Cog). According to Novo, the study’s primary completion date is September 2025, so results should be available in late 2025.

If positive, this trial would be revolutionary in several ways. First, it would introduce an entirely new mechanism to the Alzheimer’s armamentarium – targeting metabolic and inflammatory pathways via a gut hormone analog, rather than the classic approach of clearing amyloid plaques. Second, semaglutide is already widely used and known to be relatively safe (no concerns about ARIA brain swelling that plague anti-amyloid antibodies).

It’s an oral daily pill, which in AD would be hugely convenient compared to current therapies that require intravenous infusions or injections and heavy monitoring. Third, a positive outcome might force a re-think of Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, shining more light on links between insulin signaling, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration. It could spur trials of other metabolic drugs in AD (some are already in early stages, e.g. metformin is being studied in mild cognitive impairment).

That said, the bar is high in Alzheimer’s trials. To date, the only agents proven to slow disease progression are anti-amyloid antibodies like Biogen’s Leqembi (lecanemab) and Eli Lilly’s donanemab (just approved in 2025 as “Kisunla”). Those provide a modest slowing of cognitive decline (~25–35% slowing) but come with significant side effects (brain edema/bleeding in ~20% of patients).

Semaglutide, if effective, might not have as large an effect size – or it might surprise us. Even a 15–20% slowing, if paired with an excellent safety profile, could be clinically meaningful given how safe and accessible the drug is. But a negative result is also quite possible; Alzheimer’s is a graveyard of failed trials, and some worry this could be akin to past pursuits of diabetes drugs in AD (like intranasal insulin or thiazolidinediones that showed little in the end).

From an investor perspective, Novo Nordisk’s valuation doesn’t hinge on this trial – their metabolic franchise is strong regardless – but a success would open a potential multi-billion dollar new indication and could further differentiate semaglutide from competitors (imagine being the only weight-loss drug proven to also help your brain). It might also provide a life-cycle extension strategy as GLP-1 patents expire later in the decade. On the societal front, an effective oral AD therapy would be a game-changer for patient access and could ease the pressure on healthcare systems currently bracing for expensive biologic infusions for Alzheimer’s. We’ll be looking for statistically significant differences in cognitive and functional scales over the treatment period. Even secondary biomarker outcomes (like brain imaging or CSF markers) could be telling as to whether the drug engages relevant pathways.

Reinventing Depression Treatment – Biohaven’s Kv7 Ion Channel Modulator (BHV-7000) in MDD: The treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) has seen relatively few novel mechanisms in recent decades – most drugs target monoamines (serotonin, etc.). Biohaven Pharmaceuticals is aiming to change that with BHV-7000 (talagelsinor), a pill that modulates potassium ion channels (Kv7.2/7.3) in neurons.

This approach stems from the idea that tweaking neuronal excitability could alleviate mood disorders in a fundamentally different way than current antidepressants. Ion channels are notoriously tricky targets (small changes can have big effects, and many past ion channel drugs have failed due to side effects), but recent breakthroughs – like ketamine/esketamine acting via NMDA channel modulation – have reinvigorated interest in neuronal excitability as a depression treatment path.

Biohaven, which sold its migraine division to Pfizer for $11.6 billion in 2022, has been betting its future on BHV-7000 and related channel modulators. The drug was acquired from Knopp Biosciences for $100 million upfront. It selectively targets two subtypes of Kv7 potassium channels involved in stabilizing neural circuits and reducing over-excitation. After some initial exploratory trials, Biohaven launched a Phase 2/3 study in major depressive disorder, with results expected by late 2025. This is a high-stakes catalyst for the company: their stock has slumped over 50% in the past year due to pipeline setbacks, and success with BHV-7000 could reverse that fortune.

One must note that BHV-7000 had a setback: it failed a trial in bipolar disorder previously. However, depression in unipolar MDD might respond differently, and Biohaven has multiple shots on goal (they are also testing the drug in epilepsy and have others like a Kv7 modulator for chronic pain). The scientific allure here is an entirely novel antidepressant mechanism. If positive, it could usher in a new class of meds and invigorate CNS drug discovery – similar to how ketamine’s success led to a wave of glutamate-focused research in depression.

Clinicians and investors will be looking for the drug’s effect on depression rating scales (e.g. MADRS or HAM-D). Even a moderate effect, if it works in treatment-resistant patients or has a rapid onset, could be valuable. A unique angle is that ion channel modulators might have faster onset (some preclinical rationale suggests they can modulate neural networks quickly, akin to how ketamine can work within days). Additionally, the safety/tolerability profile will be crucial – past Kv7 activators had issues like dizziness or cognitive slowing, so demonstrating that BHV-7000 is tolerable at effective doses is key.

For Biohaven’s business prospects, a win would give them a platform in neuropsychiatry and possibly make them a target for acquisition (since big pharma has shown interest in novel depression treatments – J&J with esketamine, for instance). If the trial is negative, Biohaven will need to regroup, and it could cast doubt on the broader strategy of ion channel modulation for depression. That outcome might also reflect on other companies quietly exploring similar targets.

Zooming out, mental health remains a huge unmet need: more than 280 million people worldwide suffer from depression. So any breakthrough, especially one that could help the large subset not well-served by SSRIs, would have an outsized societal impact. Investors often pay less attention to neuropsych trials than, say, oncology, due to high failure rates, but BHV-7000 is one to watch because it represents something genuinely different in the pipeline. Late 2025 will tell us if this bold bet pays off.

Gene Therapies for Rare Neurological Disorders – Milestones in Rett Syndrome and Angelman Syndrome

For rare pediatric CNS diseases, H2 2025 should bring updates on some important first-in-human gene therapies. For example, Rett syndrome – a devastating neurodevelopmental disorder affecting girls, caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene – has long been considered a candidate for gene therapy, but concerns about dosing (too much MECP2 is harmful) made it challenging.

A biotech called Neurogene has developed NGN-401, an AAV9-based gene therapy with a special gene regulation switch (their EXACT™ technology) to control MECP2 expression (pharmasalmanac.com). They initiated a Phase 1 trial in early 2024 and reported interim data in April 2025 showing detectable MECP2 protein in CSF and no serious adverse events.

An update with final Phase 1 results is expected by September 2025 (pharmasalmanac.com). If the data remain positive – showing safety and hints of efficacy (even some improvement in developmental metrics or slowing of regression) – it could be a game-changer for Rett families. It would also be a proof of concept that tightly regulated gene therapies can tackle disorders where dosage is critical.

Neurogene has a partnership with Roche/Genentech, who holds an option on NGN-401, and a good result would likely trigger a $30 million milestone payment and deeper involvement from Genentech. That could provide funding and validation not only for Rett but for the broader platform (they are also pursuing Angelman syndrome with a similar approach). For the competitive landscape, note that Taysha Gene Therapies and Abeona also have Rett gene therapy programs in preclinical or early clinical stages – so success by Neurogene might raise all boats (and conversely, a setback might prompt re-evaluation of the approach).

Similarly, in Angelman syndrome (another rare genetic neurodevelopmental disorder), several gene therapy or antisense approaches are being tried. Neurogene has a program (NGN-201) that dosed its first patient in mid-2025 (pharmasalmanac.com). While no major readout is expected from that by end of 2025, we might get anecdotal early safety data. More broadly, the Angelman community is awaiting results from an antisense oligonucleotide trial by Ionis/Roche (which had some partial hold due to side effects in 2022). By late 2025 or 2026, clarity should emerge.

For now, what’s notable is that multiple CNS gene therapies are in the clinic – after years of talks, the pipeline is real. Each incremental data point (like Neurogene’s September update) builds knowledge on delivery, dosing, and functional outcomes in these ultra-rare but mechanistically straightforward disorders (loss of a single gene’s function).

Huntington’s Disease and ALS – Continuing the Pursuit

A quick note on other neurological disorders with upcoming readouts: Huntington’s disease saw high-profile failures (e.g. Roche’s tominersen in 2021), but a new Phase 3 for tominersen in a subset of patients is ongoing with data likely after 2025. ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) had some bright spots: Biogen/Ionis’s tofersen got approved in 2023 for one genetic subset (SOD1 mutations).

In sporadic ALS, a major trial of Amylyx’s AMX0035 (approved via FDA’s controversial decision in 2022) will report in late 2024 – if negative, it could cast doubt on that drug’s merits. There’s also an ongoing Phase 3 of masitinib in ALS (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) expected to report in late 2025. While not as prominent as the above, these will inform how we treat and invest in ALS, a disease which has frustrated drug developers for decades. Given the small effect of current drugs, any positive signal in ALS tends to generate excitement – but caution is warranted, as many Phase 2 “hopeful” results (e.g., BrainStorm’s NurOwn) haven’t held up in larger studies.

Psychedelics and Novel Psychiatric Treatments

It’s also worth mentioning that by 2025, the psychedelic therapy renaissance could reach a milestone: MAPS’s MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD might receive FDA approval by late 2024 or early 2025, following a successful Phase 3. If so, it would officially make MDMA the first psychedelic-assisted therapy available. That could further catalyze interest in psilocybin, LSD analogs, etc., and late 2025 might see readouts from various academic or small industry trials (for example, Phase 2 studies of psilocybin in depression at institutions like Johns Hopkins, or companies like COMPASS Pathways testing it in TRD).

For investors, many of these companies have struggled (small caps with steep losses as trials take time and cash), but actual approvals could rejuvenate the space. Business development pros at larger neuro-pharma may start paying attention if regulatory frameworks clear up. By end of 2025, we might also see initial data from GH-releasing hormone analogs in depression (Bristol’s bought Mirati’s program), or more on neuromodulation devices. However, these are more speculative and likely beyond our scope here, aside from noting the innovation ferment in psychiatry is alive.

In conclusion, the CNS arena in late 2025 presents a mix of high-risk, high-reward bets. We have an established metabolic powerhouse (semaglutide) being repurposed for Alzheimer’s – if it hits, it would challenge the dominance of amyloid-targeting drugs and perhaps open up preventative approaches for dementia (imagine giving GLP-1 drugs to at-risk middle-aged populations someday). We have a small biotech trying to revive the idea of ion channel drugs for mood disorders – success could create an entirely new category of antidepressants, while failure will remind everyone why CNS is hard and perhaps shift focus back to more proven targets or psychosocial interventions.

And we have the slow but steady march of gene therapies into chronic brain diseases – a technically daunting but potentially transformative endeavor if these can be made safe and effective. For investors and BD professionals, the CNS space is one where diversification is key (because individual trials have low success probabilities), but the payoff can be substantial (Alzheimer’s alone is a >$10 billion/year market for even moderately effective drugs, and something like a Rett syndrome cure, while affecting fewer patients, can still justify premium pricing).

Not to mention, companies achieving CNS breakthroughs often attract partnerships or acquisition interest given big pharma’s perennial appetite for neurology assets (witness Lilly buying Prevail for gene therapies, Biogen’s deals in Parkinson’s, etc.).

Expect the rest of 2025 to bring clarity on these bold CNS experiments – either ushering in new paradigms or sending researchers back to adjust their hypotheses. And with the neurodegenerative disease population aging globally, any progress here will have humanitarian impact far beyond the financial metrics.

Rare Diseases & Emerging Technologies: Gene Therapies, RNA Medicines, and CRISPR

Beyond the headline-grabbing common diseases, late 2025 will also see crucial developments in rare diseases and novel therapeutic technologies. This is the realm where early-stage trials and innovative platforms often debut – think gene therapies for ultrarare disorders, CRISPR gene editing in humans, microbiome-based therapies, and other cutting-edge modalities. While each individual indication may be small, collectively this area is a hotbed of scientific progress and often a leading indicator of where medicine is heading. Moreover, from an investment standpoint, these are the catalysts that can turn tiny biotechs into acquisition targets overnight if the data are compelling (as larger companies seek to buy into validated platforms).

Gene Therapy Nearing Fruition – Examples in Rare Skin and Blood Disorders

A number of gene therapy programs are reaching maturity. One example is Castle Creek Biosciences’ work in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB), a devastating genetic skin disorder causing fragile skin and chronic wounds. Castle Creek’s approach, called D-Fi™ (beremagene geperpavec), is an ex vivo gene therapy: a patient’s own skin fibroblasts are genetically modified (with a functional collagen VII gene) and then reintroduced via injection into wounds. In March 2025, Castle Creek announced that a Phase 3 trial of D-Fi met its primary endpoint, showing a statistically significant reduction in wound surface area after 6 months.

The treated wounds had much better healing compared to placebo injections, indicating the therapy was effective. This was a landmark achievement – it’s one of the first gene therapies to succeed in a dermatologic condition. As a result, Castle Creek is on track to submit a Biologics License Application (BLA) in Q4 2025. If approved in 2026, D-Fi would become the first autologous cell-based gene therapy for DEB, addressing a long-unmet need.

The significance extends beyond one disease: it validates the ex vivo fibroblast gene therapy approach, which could be applied to other skin disorders or localized diseases. Castle Creek, for instance, expanded its pipeline by acquiring a program for hereditary tyrosinemia (a metabolic liver disease) that uses a lentiviral vector delivered in vivo.

They showed in 2025 that a single infusion led to durable normalization of liver enzymes in a Phase 1, demonstrating gene therapy’s potential in metabolism. That program (LV-FAH) heads into Phase 2 in late 2025. For investors, Castle Creek’s success in DEB attracted a $75 million royalty financing from Ligand, and one could envision either partnering or acquisition interest if their BLA looks solid. Their dual-platform (ex vivo for skin, in vivo for liver) also illustrates how small companies might tackle multiple niches.

Another rare disease milestone expected is from Azitra, Inc., which is taking a unique microbiome therapy angle. Azitra engineered a strain of bacteria to secrete therapeutic proteins on the skin. Their lead candidate AZT-01 is a topical live biotherapeutic for the same DEB skin condition. Interim data from a Phase 2/3 trial showed that 60% of treated chronic wounds achieved closure by 12 weeks, vs only 15% in placebo – a very dramatic difference.

That suggests strong efficacy. The Phase 3 readout is expected in Q4 2025, potentially positioning AZT-01 to be the first approved microbiome-based therapy for a genetic disease. While one might wonder if two very different approaches (Castle Creek’s gene therapy vs. Azitra’s bacteria) would compete in DEB, in reality severe DEB may need combination approaches and any new treatment is welcome. If Azitra’s data hold up, it also provides proof that engineered probiotics can treat disease, which could spur interest in microbiome therapies beyond the current focus (mostly GI and C. diff infection).

Gene Editing in the Clinic – CRISPR and Base Editing Updates: The year 2025 is a pivotal time for in vivo gene editing. By now, multiple patients have been dosed with CRISPR-based therapies in trials for conditions like transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR), hereditary angioedema, and hypercholesterolemia. While some landmark results came in earlier (e.g. Intellia’s NTLA-2001 showing >90% knockdown of TTR protein in 2021), late 2025 will bring further updates that test the durability and safety of these approaches with longer follow-up and more patients.

For instance, Intellia Therapeutics is expected to present longer-term data from the expanded Phase 1 of NTLA-2001 for ATTR amyloidosis. This was the first systemic CRISPR injection in humans, and early results showed profound reduction in the disease-causing protein. Investors will watch whether those levels remain low over time (suggesting a permanent edit) and that no late safety concerns (like off-target effects) emerge.

Similarly, Intellia’s second program, NTLA-2002 for hereditary angioedema (which also uses CRISPR to knock out a liver gene), had shown that a one-time dose essentially abolished patients’ debilitating swelling attacks for many months. By late 2025, we should see if those patients remain attack-free or if they eventually start to relapse – which would indicate whether repeat dosing might be needed or not.

Meanwhile, a next-generation form of editing – base editing – is in trials via Verve Therapeutics. Verve’s approach can make more subtle single-letter DNA changes. They started with a gene called PCSK9 (to permanently lower LDL cholesterol) and dosed the first human in 2022 in New Zealand. That trial (the Heart-1 study) provided some initial safety data. In 2024, Verve began a second program VERVE-201 targeting ANGPTL3, another gene that regulates cholesterol and triglycerides.

This one is aimed at homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) and refractory hyperlipidemia. Verve has indicated they expect a program update for VERVE-201 in H2 2025 (vervetx.gcs-web.com), likely sharing how the first few patients have fared. The update might include measures of editing efficiency (did ANGPTL3 protein drop to near-zero?), any adverse events, and perhaps early lipid profile changes. Given VERVE-201’s first patient was only dosed in late 2024, by end of 2025 we might have 6–12 month data on a handful of patients. Even anecdotal evidence of safe, effective base editing in humans would be a major milestone (ir.vervetx.com). It would differentiate base editors from CRISPR in terms of precision and could bolster confidence in applying this to other diseases (Verve themselves have a plan for an Lp(a) base editor next).

The Business of Gene Editing

On the business side, regulatory and commercial progress is also unfolding. By 2025, the first CRISPR-based therapy (exa-cel for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, from CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex) is expected to receive approval decisions in major markets. Assuming approval (many expect by late 2024 or early 2025 in the U.S.), the second half of 2025 will be the first real-world launch of a CRISPR medicine. While exa-cel is an ex vivo therapy (editing cells outside the body), its progress will influence investor sentiment for the whole field.

If the launch goes well and patient uptake is strong (despite a likely >$1 million price), it proves that gene editing can be a viable business. If there are hurdles (e.g. reimbursement issues, safety hold-ups, manufacturing bottlenecks), it might temper enthusiasm. Companies like Editas Medicine (working on their own sickle cell therapy with a different editing approach) will either be buoyed or pressured by exa-cel’s trajectory.

It’s noteworthy that as of 2025, larger pharmaceutical companies are getting involved in gene editing through partnerships – e.g. Bayer with its unit AskBio is exploring gene editing, Novartis invests in a BEAM partnership for gene editing in certain blood disorders, etc. Late 2025 data might catalyze more deals: a particularly good Verve or Intellia result could prompt a deep-pocketed pharma to partner on those or similar programs, to avoid being left behind in the genomic medicine race.

RNA Medicines – Beyond siRNA: RNA Editing and Antisense Catalysts

We already touched on RNA editing with Wave Life Sciences in the immunology section. To reiterate, their Q3 2025 multi-dose data in AAT deficiency will be a bellwether for that sub-field. Success would show that you can achieve therapeutic protein restoration by editing mRNA repeatedly, which is conceptually huge (fixing genetic diseases without touching the DNA). Conversely, if repeat dosing triggers immune reactions or loses efficacy, it flags challenges ahead. Competitor Korro Bio will also have initial data around that time, so analysts will compare notes across companies.

In traditional antisense and RNAi, a few late 2025 events stand out. Ionis Pharmaceuticals and partner GSK have a Phase 3 reading out in familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) for an LPL enhancer antisense (vupanorsen was discontinued, but another ASO for ApoC-III maybe). Also, an important regulatory event: we expect Novartis’s inclisiran (an siRNA for LDL-c) to possibly gain expanded indications or updated outcome data by then, after its initial approval in 2021.

And Alnylam’s patisiran (an siRNA for ATTR amyloidosis) – they sought label expansion to ATTR cardiomyopathy in 2023; the FDA’s decision (initially negative in US, positive in EU) might see further developments or trial follow-ups by 2025. These aren’t exactly “new trial readouts” in H2 2025, but rather the maturation of earlier readouts into real-world impact. They matter because they reflect how regulators are viewing surrogate endpoints vs outcomes (e.g., FDA wanted outcomes for patisiran’s cardio indication).

By late 2025, we should have full results from the APOLLO-B trial (patisiran in cardiomyopathy) presented – which will either support Alnylam trying again for approval or confirm the FDA’s skepticism. Similarly, for pelacarsen we discussed, if any interim signals leak or if competitive Lilly’s antisense emerges, it could sway Ionis’s valuation.

One more new modality – Live Cell Therapies for Autoimmunity

An emerging area to mention: using living cells (not genetically modified, but as functional treatments). For example, SIG-005, a therapy consisting of encapsulated human cells engineered to produce enzyme for MPS-1 (a lysosomal disease), might have early results by late 2025. Also, in type 1 diabetes, Vertex’s stem cell-derived islet cells (VX-880) has ongoing trials – early results in 2022 showed a few patients became insulin-independent.

By late 2025, more data from Vertex or others (ViaCyte’s program, now partnered with CRISPR Therapeutics for an immunoprotected version) could emerge, indicating how close we are to a functional cure for T1D. Each of these is a small step, but collectively they show the expansion of therapeutic frontiers.

How the Market is Embracing Innovation: It’s worth noting that after a tough 2022–2023 bear market, the biotech financing environment began to thaw in 2024. By 2025, venture funding and IPOs have been ticking back up (genengnews.com).

The success of innovative trials has a feedback loop with funding: positive readouts in H2 2025 for cutting-edge therapies could accelerate the rebound in biotech IPOs and VC investment. For instance, a great RNA editing result might lead to IPOs of other RNA editing startups or big Series B/C funding rounds. Conversely, if many of these novel tech trials flop, it could scare generalist investors again and prolong the risk-off sentiment.

As of late 2025, there’s cautious optimism that the biotechnology sector is emerging from a slump, aided by important clinical wins. The initial public offering market for biopharma is expected to bounce back further in 2025, after showing glimmers of life in late 2024. There’s also hope for a revival in M&A – big pharmas flush with cash and facing their own patent cliffs are always on the lookout, and nothing spurs acquisition like compelling Phase 2/3 data.

If H2 2025 delivers several positive surprises in trials, we might see a surge of takeovers or licensing deals announced by year-end or in early 2026. On the other hand, continued trial disappointments could keep valuations subdued and deals on the conservative side. It’s a dynamic interplay where science and market sentiment feed each other.

Conclusion and Outlook

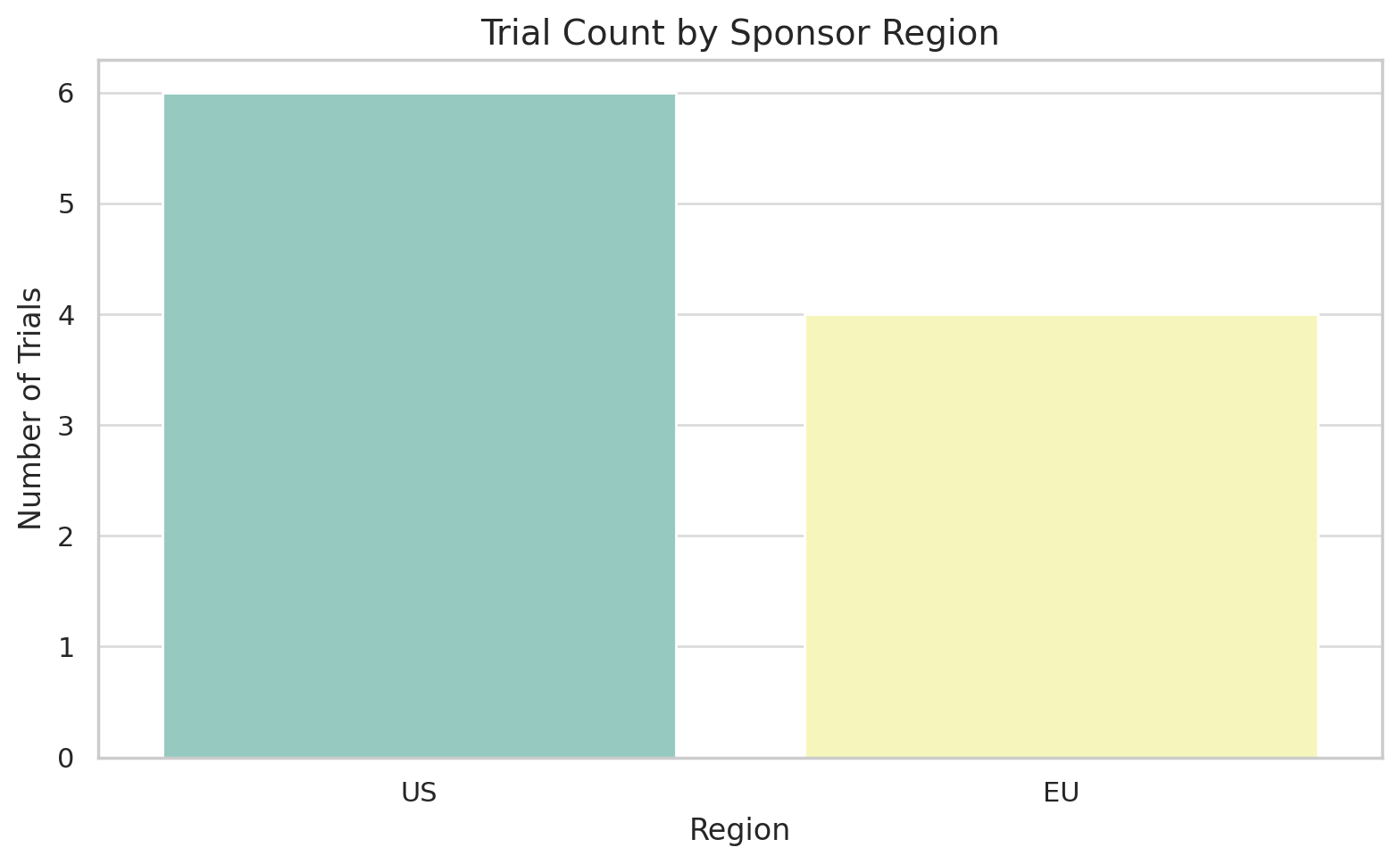

As we have detailed, the second half of 2025 is brimming with pivotal clinical milestones across a panorama of therapeutic areas. From multi-billion dollar blockbusters in waiting, to the first glimmers of entirely new therapeutic classes, these trial readouts carry profound implications for patients, healthcare systems, and the fortunes of companies both large and small. Geographically, innovation is truly global – we see crucial contributions from American, European, and Asian firms alike (e.g. a Swiss biotech leading in dermatology, a China/U.S. partnership challenging the oncology status quo, etc.).

There is no single therapeutic focus dominating the landscape; rather, the excitement spans metabolic disease, immunology, oncology, neurology, rare genetic disorders, and infectious diseases. This breadth is itself noteworthy – it suggests a healthy diversification in R&D, where advances in one field (like GLP-1s in diabetes) cross-pollinate into others (like Alzheimer’s) and where multiple modalities (small molecules, antibodies, RNAs, cells, gene edits) are proving their worth.

For investors and business development professionals, H2 2025 is a time to be both vigilant and strategic. The sheer volume of data requires careful analysis: differentiating true breakthroughs from mere “nice-to-have” incremental improvements. Successful trials could rapidly re-rate a company’s valuation upward or make it an attractive acquisition target – as seen historically (e.g. positive cancer data leading to buyouts at high premiums).

Already in 2025 we saw Merck attempt to buy MoonLake on Phase 2 data; one can imagine what Phase 3 success might trigger. Similarly, small-cap biotechs like Wave Life Sciences or Biohaven could become hot properties if their novel approaches yield clinical proof. Big Pharma will be watching closely to see which assets might fill their pipeline gaps – for instance, if Sanofi’s amlitelimab falters, they might shop for another immunology asset; if Lilly’s oral obesity pill disappoints, others with alternative mechanisms (e.g. Amgen’s small-molecule or Pfizer’s next-gen oral) might gain favor.

Conversely, trial failures will also inform strategy: resources may shift away from modalities that underperform. If, say, BTK inhibitors fail yet again in MS, companies might halt those programs and redirect funds to other neuroscience projects (or consider acquisitions of more promising technologies). If the PD-1/VEGF approach fails to show survival benefit, the scramble for those assets could cool, affecting numerous partnerships.

It’s also crucial to consider the competitive timing of these readouts. Many are clustered around year-end 2025, which means a lot of information will hit at once, perhaps at big medical conferences (like the European Society for Medical Oncology in the fall, or the American Heart Association meeting, etc.). Companies that can deliver at those venues often see an outsized share-price impact due to heightened visibility. Additionally, regulatory bodies are watching too – positive trial results in H2 2025 will lead to New Drug Application filings in 2026 and advisory committee meetings perhaps within 2026, meaning some of these could become marketed products by 2026–27. Thus, the back-half of 2025 is effectively setting the stage for what therapies will define the standard of care as we enter the late 2020s.

In macro terms, the success of these trials will also influence public and political narratives around the industry. High-profile wins (like an Alzheimer’s pill or a weight-loss breakthrough) capture public imagination and can impact everything from drug pricing debates to healthcare policy. They can also spur investment in biotech from non-traditional quarters, as optimism rises. On the flip side, disappointments in long-hyped areas (imagine if all the Alzheimer’s non-amyloid approaches fail, or if a safety scare hits gene therapy) could invite criticism or skepticism about whether the billions poured into R&D are delivering enough.

One thing is certain: the second half of 2025 will not be boring for the biopharma sector. The sheer volume of critical readouts means volatility – scientific and financial – will be high. Companies and investors would do well to stay diversified and to base decisions on rigorous analysis of the data (not just hype), as some bets will pay off handsomely while others may fall flat. If the majority of these anticipated readouts are positive, we could be entering 2026 with unprecedented momentum: a reinvigorated biotech funding environment, a slew of new products on the horizon, and perhaps the dawn of new treatment paradigms (like metabolic treatments for neurodegeneration or gene editing cures).

If many are negative, 2026 could instead be a period of retrenchment and reevaluation, with the industry going back to the drawing board in key areas.

Member discussion