Magic Bullets, Reloaded: The Global Rise of Antibody–Drug Conjugates

The Return of the “Magic Bullet”

In 1908, the German scientist Paul Ehrlich coined the term “Zauberkugel” – magic bullet – envisioning a drug that could target disease with pinpoint accuracy while sparing healthy tissue. Over a century later, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) aim to fulfill that vision. An ADC couples a tumor-seeking monoclonal antibody with a lethally potent chemotherapy payload, joined by a molecular linker.

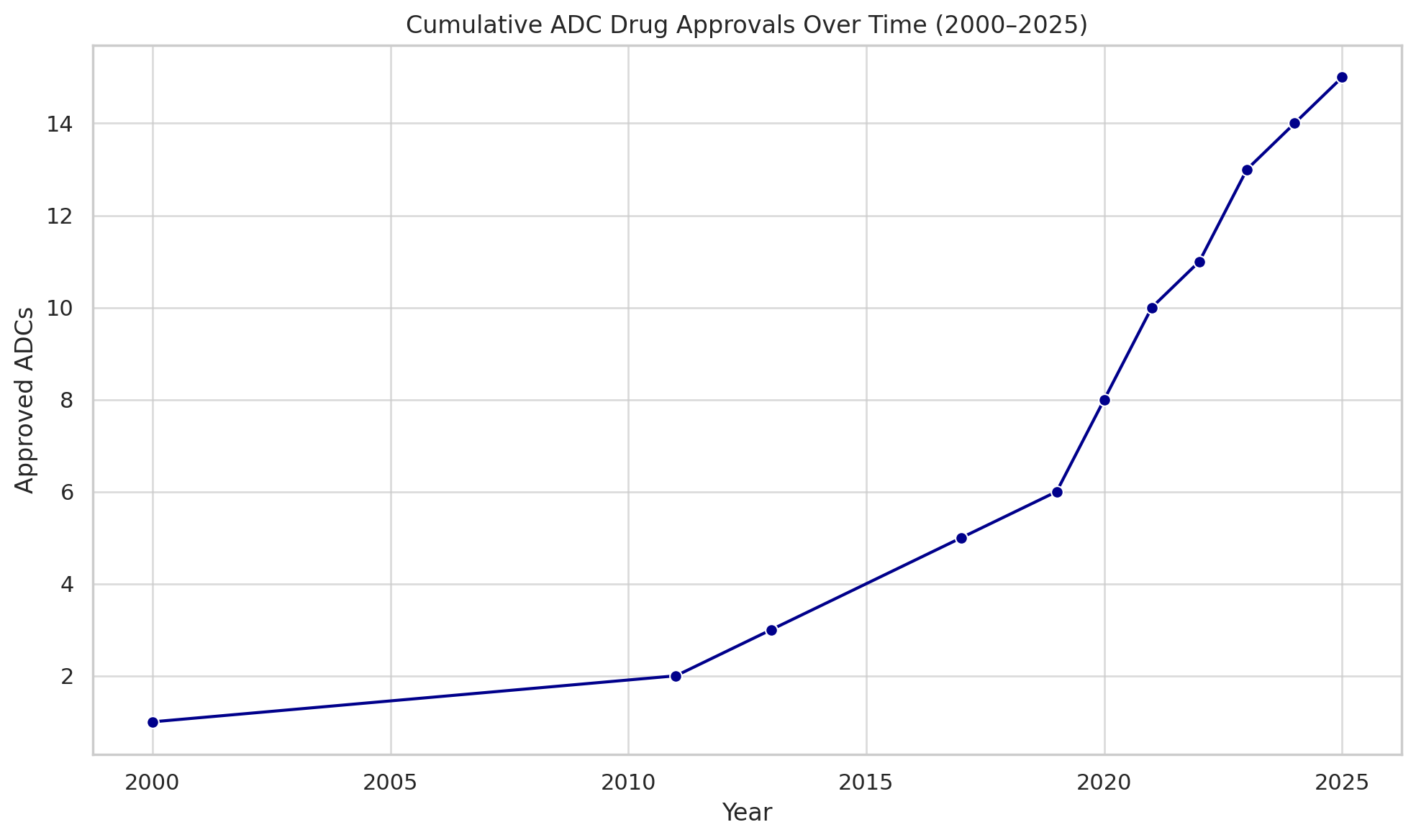

This elegant combination turns an ordinary antibody into a guided missile – delivering a toxic blow inside cancer cells and limiting collateral damage. After decades of development marked by both setbacks and breakthroughs, ADCs are enjoying a renaissance in oncology. Regulators have approved around 15 of these armed antibodies (as of mid-2025) for cancers ranging from leukemias to breast and lung tumors (dcatvci.org). Pharmaceutical giants are now scrambling to load their arsenals with ADCs, betting billions that these biologic missiles could be the next big artillery in the war on cancer.

Yet amid the optimism, a dose of skepticism is warranted. ADC technology is not entirely new – the first was approved a quarter-century ago – and early efforts were plagued by toxic side effects and technical hurdles. Even today’s successes come with caveats: many ADCs can cause severe side-effects (eye damage, liver toxicity and more), and only a handful have achieved blockbuster status in sales. Industry observers are asking whether the ADC explosion will truly revolutionize cancer care or if it resembles past oncology “gold rushes” that yielded more hype than long-term change.

In an era when PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors – immunotherapy drugs that unshackled the immune system – have reshaped oncology treatment and generated over $45 billion in annual revenue (living.tech), can ADCs follow a similar trajectory? The current ADC frenzy, complete with sky-high company valuations and headline-grabbing acquisitions, bears some hallmarks of the immunotherapy boom a decade ago. This article examines the science and history behind ADCs, dissects the global pipeline and financial investment surge, profiles key players (from Seattle to Shanghai), and assesses whether ADCs are living up to their billing or riding a biotech hype cycle.

How ADCs Work and Evolve

ADCs build on a simple premise: targeted drug delivery. A monoclonal antibody, engineered to home in on a protein expressed on cancer cells, is chemically tethered to a powerful cytotoxic compound. The antibody serves as the guidance system, bringing the toxic payload directly to cancer cells; once the ADC is internalized into the tumor cell, the linker releases the drug, killing the cell from withindcatvci.org. By concentrating the chemotherapy effect at the tumor site, ADCs aim to maximize tumor kill and minimize systemic toxicity – the very definition of Ehrlich’s magic bullet. In practice, achieving this selectivity is challenging.

The design of the linker (stable in the bloodstream, but cleavable inside target cells) and the potency of the payload (many times stronger than standard chemo) are critical. Early-generation ADCs often fell short: the first approved ADC, Mylotarg (gemtuzumab ozogamicin) in 2000, linked an anti-leukemia antibody to a potent toxin but used a linker that proved too fragile. The drug sometimes released its toxic payload prematurely, causing severe side effects without sufficient benefit. Within three years, Mylotarg was pulled from the market due to safety concerns and limited efficacy. Ehrlich’s magic bullet seemed to have backfired.

It took another decade for ADCs to redeem themselves. Technological advances – humanized antibodies, more stable linkers, and ultra-potent payloads – led to the next wave of ADCs that finally delivered convincing results. In 2011, Seattle Genetics (now Seagen) and Takeda won approval for Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin) in lymphomas, followed in 2013 by Roche’s Kadcyla (ado-trastuzumab emtansine) for HER2-positive breast cancer. These second-generation ADCs validated the approach by achieving solid clinical outcomes in cancers with unmet need, all while keeping toxicities manageable. Regulatory milestones soon piled up: Pfizer’s Besponsa (inotuzumab ozogamicin) for acute leukemia and Polivy (polatuzumab vedotin) for lymphoma, an AstraZeneca-partnered Lumoxiti (moxetumomab pasudotox) for hairy-cell leukemia, and more.

Notably, Enhertu (fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan) – an ADC from Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca – gained approval in late 2019 and has since demonstrated remarkable efficacy against HER2-expressing breast cancers, including tumors once thought “untargetable” by existing drugs. By 2020, a flurry of FDA approvals ensued: Immunomedics’ Trodelvy (sacituzumab govitecan) for triple-negative breast cancer and GlaxoSmithKline’s Blenrep (belantamab mafodotin) for multiple myeloma both reached the market.

In 2021 and 2022, ADC Therapeutics’ Zynlonta (loncastuximab) for lymphoma, Seagen’s Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin) for cervical cancer, and ImmunoGen’s Elahere (mirvetuximab soravtansine) for ovarian cancer expanded the roster. By mid-2025, 15 ADC drugs had been approved by the U.S. FDA (and at least 17 worldwide when including approvals in other markets). The timeline below highlights the accelerating pace of approvals after the late 2010s, following a slow start after 2000:

Cumulative number of ADC drugs approved globally (FDA and other agencies). After a lone pioneer in 2000, approvals picked up notably from 2019 onwards, reaching 15 by mid-2025. (dcatvci.org)

Each success built confidence that ADCs could become a mainstay modality in oncology, complementing surgery, radiation, traditional chemo, and immunotherapy. Enhanced engineering has played a key role. Modern ADCs use clever linker chemistries that release drug only under specific conditions (such as the acidic environment inside a cell or when exposed to certain enzymes), and they often carry multiple warhead molecules per antibody to amplify lethality.

The warheads themselves are often too toxic for standalone use (e.g. auristatins, maytansinoids, or exatecans), packing 100–1000× the potency of standard chemo agents. In essence, scientists have reloaded Ehrlich’s magic bullets with far deadlier explosives, but with guidance systems precise enough (in theory) to avoid blowing up healthy cells. As one group of researchers described it, an ADC is a “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy (biospace.com).

That potent promise explains why the pharmaceutical industry has now fully embraced ADCs – and also why careful aim is paramount. Even the best missiles can misfire. Some ADCs have failed in trials due to insufficient efficacy or unexpected toxicity. For example, GSK’s Blenrep, despite its initial approval for myeloma, was pulled from the U.S. market in 2022 after confirmatory trials fell short, illustrating that risks remain. Nonetheless, the overall trajectory for ADCs is one of refinement and expansion – targeting new tumor markers, improving delivery, and venturing beyond oncology into autoimmune diseases and other conditions in early research.

A Pipeline Booming Across the Globe

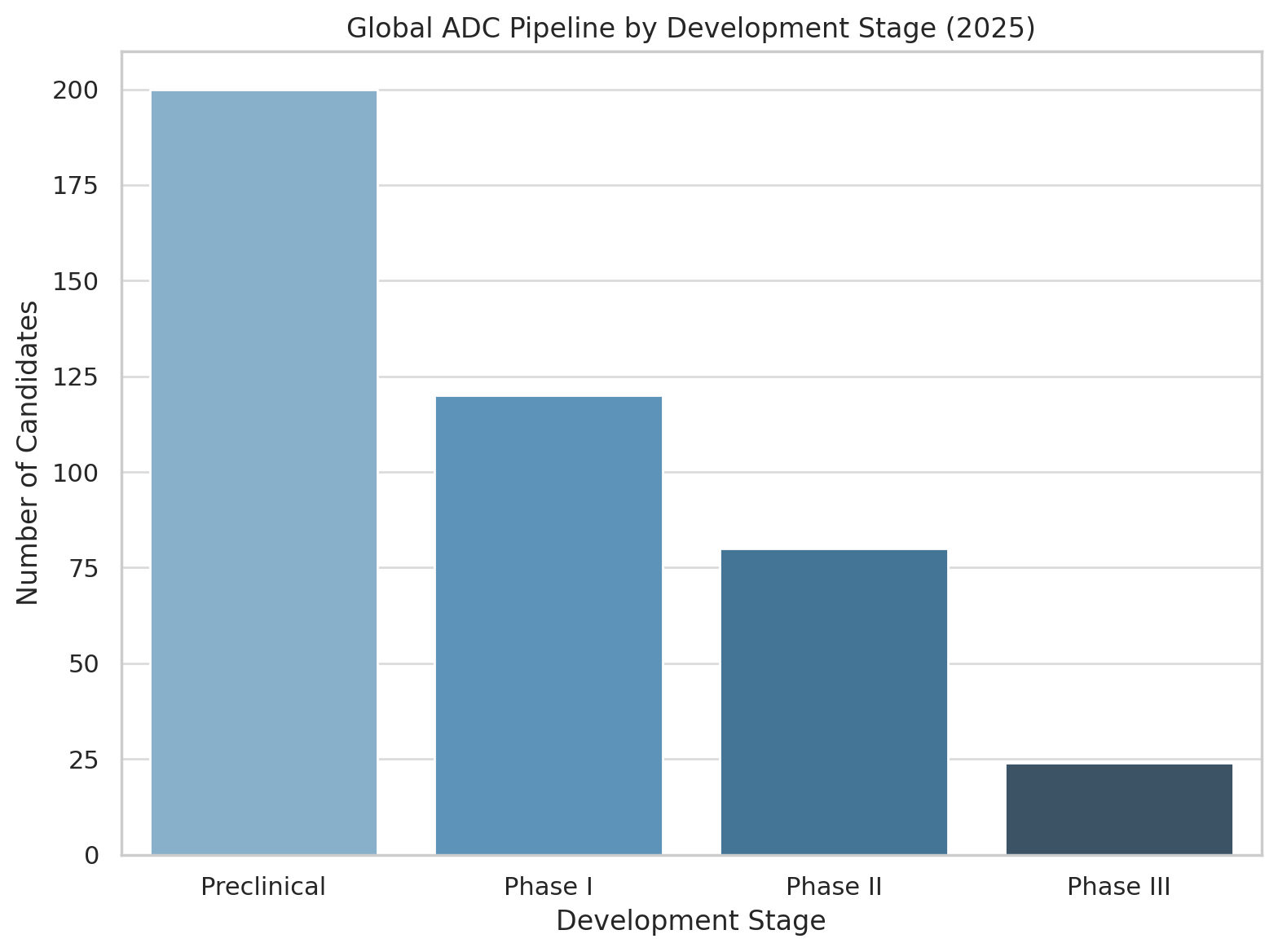

Behind the dozen-plus ADCs already saving patients lies a vast pipeline of next-generation conjugates. ADC development has well and truly gone global. By 2025 there were over 400 ADCs in development worldwide, with more than 200 of those already in clinical trials (the remainder in preclinical stages). Dozens of new ADC candidates enter Phase I testing each year as biotechnology startups and pharma companies large and small pile into the field. The chart below breaks down this burgeoning pipeline by development phase:

Global ADC pipeline by stage (2025). A majority of projects remain in preclinical R&D, and among clinical-stage ADCs the emphasis is on early development (Phase I/II). Only a few dozen have reached Phase III trials.

As the graphic makes clear, the lion’s share of ADC activity is in early-stage trials. Over half of all ADC candidates are still in discovery or preclinical testing, and of the ~200 in human trials, the great bulk are in Phase I or II. Fewer than 25 ADCs have advanced to Phase III (jhoonline.biomedcentral.com). This reflects both the nascency of many programs and the sobering reality that developing a safe and effective ADC remains challenging.

Optimism abounds, however, because the successes of first- and second-generation ADCs have de-risked the concept to a degree – demonstrating that if you get the biology and chemistry right, an ADC can deliver knockout blows to tumors that were previously intractable. Now, a crowded field of competitors is racing to craft the next ADC breakthroughs, targeting an ever-wider array of tumor antigens: from solid tumors like lung, breast, and colon cancers to blood malignancies and even rare cancers.

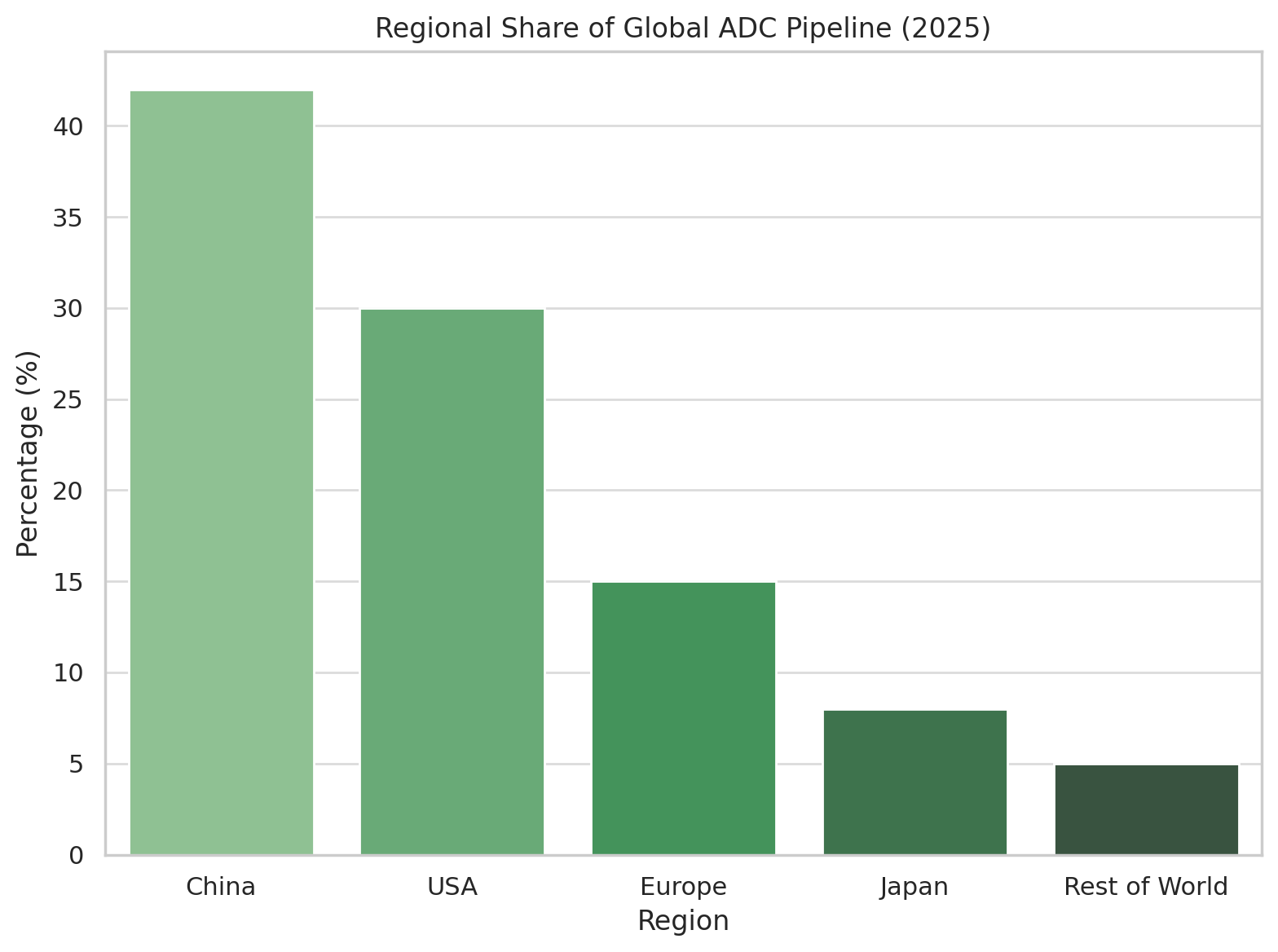

Geographically, a striking shift is underway: China has surged to the forefront of ADC development. Once primarily an import market for cancer drugs, China is now an innovator – its biotech firms are responsible for an outsized portion of the global ADC pipeline. By late 2024, China held over 42% of all active ADC drug projects in the world. In fact, according to industry analytics, half of the world’s top 10 organizations by number of ADC pipeline candidates are Chinese companies. This reflects a deliberate strategic focus by Chinese biotech on ADCs, buoyed by significant talent and investment pouring into the field. As shown below, China now leads in sheer pipeline share, followed by the United States, with Europe and Japan trailing:

Regional share of active ADC development programs (clinical and preclinical). Chinese companies and institutes now account for an estimated 40–45% of the global ADC pipeline, surpassing North America (ubs.com).

The Chinese ADC boom is exemplified by companies like Biocytogen and RemeGen. Biocytogen, an antibody platform company, reportedly has 23 ADC projects in the works – although tellingly, all are still in discovery or preclinical stages (expresspharma.in). Another rising star, ProfoundBio, has built a portfolio of 13 ADC candidates; it is among the most advanced of the Chinese cohort, with three ADCs already in Phase II trials and one (dubbed “Rina-S”) granted FDA Fast Track designation for ovarian cancer. Meanwhile RemeGen, based in Yantai, made history with one of China’s first domestic ADC approvals: disitamab vedotin, branded Aidixi, for HER2-expressing gastric cancer.

That ADC – akin to a local version of Kadcyla/Enhertu – secured Chinese regulatory approval in 2021, and RemeGen promptly inked a lucrative $2.6 billion co-development and licensing deal to let Seagen (now part of Pfizer) develop and commercialize it globally (ppf.eu). Deals like this highlight a broader trend: Western pharma companies are eagerly scouting Chinese A

DC innovations and paying handsomely for rights.

Indeed, Chinese biotechs have become prolific partners in the ADC arena. A notable example came in October 2023 when Merck & Co. agreed to develop seven preclinical ADC programs from China’s Kelun-Biotech, in a collaboration worth up to $9.5 billion in milestones. And in January 2025, Roche kicked off the year by licensing an ADC from China’s Innovent Biologics (targeting the c-Met receptor in lung cancer) for $1.08 billion in potential payouts.

These partnerships underscore that Chinese firms are not just developing ADCs for their home market – they are becoming an exporter of innovation, with global pharma tapping into China’s ADC talent pool and R&D engine. Local incentives, from government R&D programs to a faster review process for innovative drugs, have created fertile ground for ADC research in China (ubs.com). The Yangtze River Delta region, home to many of these companies (e.g. ProfoundBio in Suzhou, MediLink in Shanghai), has emerged as an ADC innovation hub, leveraging strong research universities and a thriving biotech ecosystem.

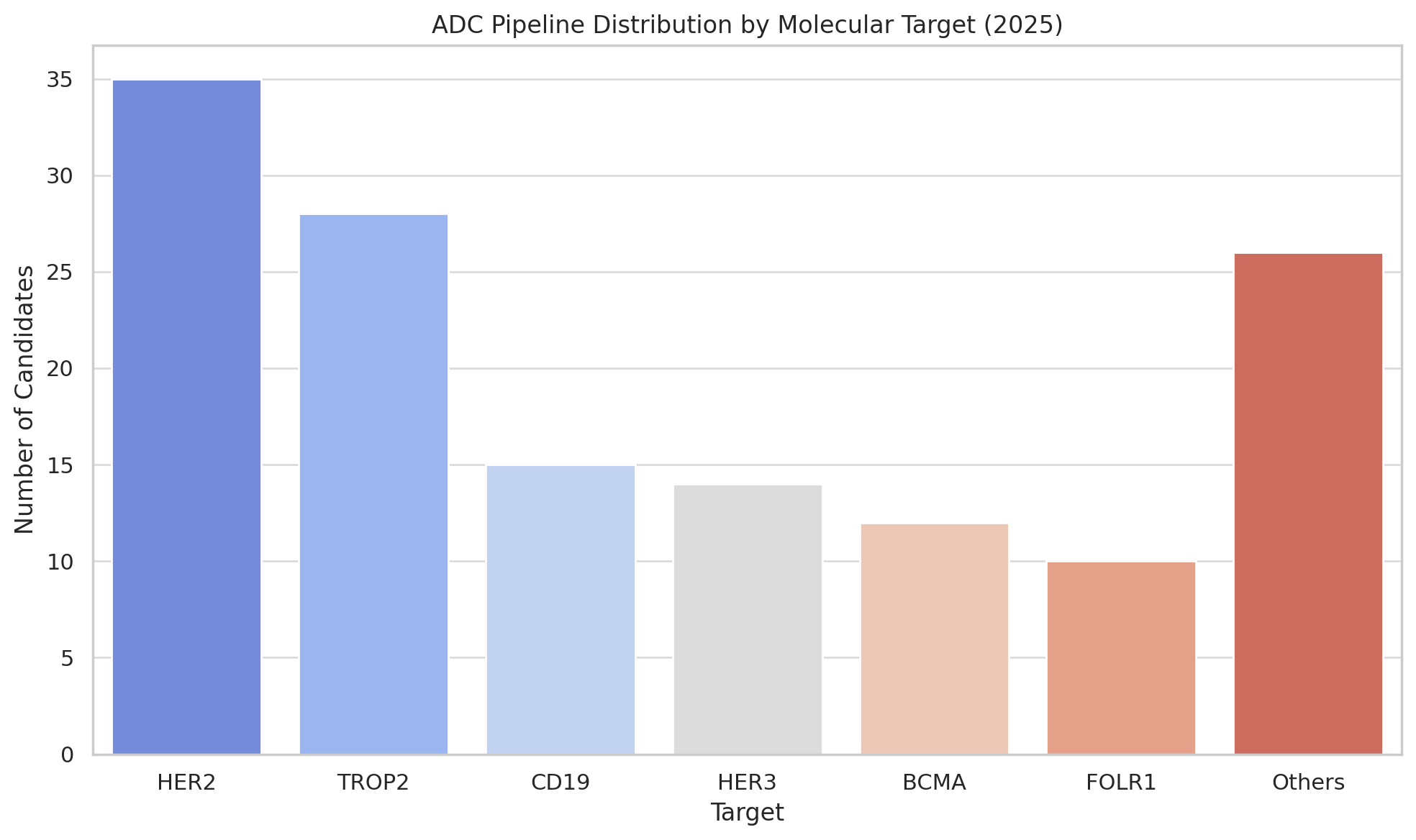

It’s worth noting that the pipeline diversity is increasing too. Early ADC efforts mostly targeted a handful of antigens (like HER2, CD19, CD22, TROP-2). Now, developers are exploring dozens of new targets – including “cold” tumors and novel markers – and even experimenting with bispecific ADCs (antibodies that recognize two antigens to enhance tumor specificity) and dual-payload ADCs (carrying two different drugs for a one-two punch). At the 2025 AACR cancer research meeting, for instance, Chinese researchers unveiled ADCs with two payloads as a next frontier in design. Other innovators are combining ADCs with immunotherapy (for example, pairing an ADC with a PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor to both attack the tumor directly and rally the immune system).

All this paints a picture of a rich and competitive pipeline – one that is global in scope and brimming with technical ingenuity. Of course, not all these projects will succeed. Many will flame out due to safety issues or lack of efficacy; some will be beaten to market by rivals. But with hundreds of shots on goal, the odds are good that the coming years will see a steady flow of new ADC approvals, each aiming to address cancers that remain poorly served by existing therapies.

Big Pharma Bets Big on ADCs

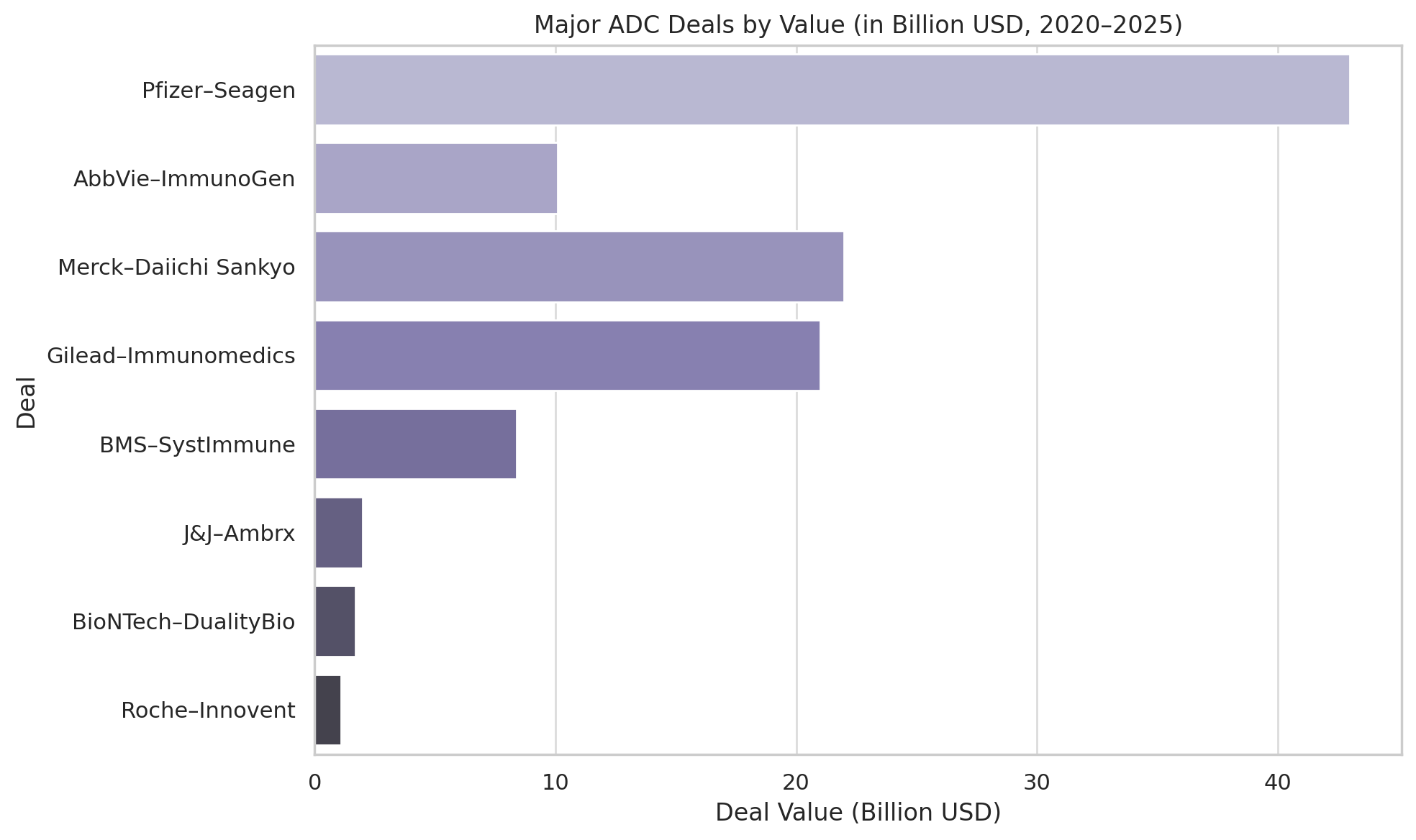

If the science of ADCs has matured, the business of ADCs has boomed. In the last few years, pharmaceutical companies have poured unprecedented sums into this field – through acquisitions of ADC-focused biotechs, billion-dollar licensing deals, and rich R&D collaborations. The frenzy reached a crescendo in 2023, a year some dubbed “the ADC gold rush.” The most dramatic vote of confidence came in March 2023, when Pfizer announced a $43 billion acquisition of Seagen, the Seattle-area biotech that pioneered Adcetris and built a leading ADC portfolio.

That deal – one of the largest pharma acquisitions in recent history – instantly gave Pfizer four approved ADC drugs (Adcetris, Padcev, Tivdak, and others), not to mention a pipeline of next-generation ADC technologies. It signaled that big pharma sees ADCs as a strategic pillar for the future of its cancer franchise. As Pfizer’s CEO Albert Bourla put it, the Seagen buy gave them the “crown jewels of targeted oncology.”

Pfizer was not alone. In early 2024, AbbVie – a company known for immunology and traditional antibody drugs – splashed out $10.1 billion to acquire ImmunoGen, the Massachusetts biotech behind the ovarian cancer ADC Elahere. This deal not only brought AbbVie a marketed ADC (Elahere) but also a pipeline of ADC candidates and technology. (It’s worth noting AbbVie already had one foot in the ADC door: it had co-developed an ADC for leukemia, Mylotarg, years earlier with Pfizer, and its own internal programs were progressing, including telisotuzumab vedotin for lung cancer – which the FDA accelerated approved in 2025 as Emrelis).

Another major move came from Johnson & Johnson, which in 2023 agreed to pay $2 billion to acquire Ambrx Biopharma (dcatvci.org) – a San Diego company developing ADCs with a specialized linker/payload platform (Ambrx’s assets included ARX-788, a HER2-targeted ADC, and others in prostate and renal cancers). Notably, Ambrx had partnerships in China and the US, and J&J’s buyout illustrated the East–West convergence: Western pharma coveting platforms that often have roots in both American and Asian research.

If outright acquisitions are one strategy, hefty licensing partnerships are another. In perhaps the most eye-popping alliance, Merck & Co. (known as MSD outside the US) forged a collaboration with Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo in October 2023 valued up to $22 billion. For an upfront payment of $4 billion and billions more in milestones, Merck gained co-development rights to three of Daiichi’s ADC candidates – including patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-targeted) and others in early trials.

This deal followed on the heels of Daiichi’s existing ADC partnership with AstraZeneca (struck in 2019 for up to $6.9 billion) that had already yielded Enhertu and another ADC called datopotamab deruxtecan (approved in 2025 as Datroway for HR-positive breast cancer). Clearly, big pharma is willing to double down on ADC bets. Merck’s and AstraZeneca’s rivalry for Daiichi’s prize assets underscores how critical ADCs have become in the scramble to dominate oncology markets.

Other notable recent deals read like a who’s-who of pharma: In late 2023, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) agreed to pay up to $8.4 billion for rights to a bispecific ADC from a small US–China biotech called SystImmune. Around the same time, Merck & Co. expanded its tie-ups with China’s Kelun-Biotech in deals approaching $9.5 billion for multiple preclinical ADC programs. European players are in the mix too – Boehringer Ingelheim in January 2025 paid $1.3 billion to license ADC linker-payload technology from the Dutch firm Synaffix (a specialist now owned by Lonza), aiming to apply it across its oncology portfolio. And as mentioned, Roche kicked off 2025 by spending $80 million upfront (and over $1 billion in milestones) to collaborate on Innovent’s c-Met-targeted ADC.

It’s instructive to consider the scale of investment pouring into ADCs. By one estimate, the total value of major ADC-related deals from 2022 through early 2025 easily exceeds $80 billion when including acquisitions and partnership milestones. The current approved ADC drugs collectively generated about $8.5 billion in sales in 2023, but analysts forecast a more than fivefold increase (to ~$45 billion) in annual ADC sales by 2030 (expresspharma.in). That kind of growth – a 433% jump in seven years – would mirror the meteoric rise of PD-1/L1 checkpoint inhibitors in the 2015–2021 period.

Small wonder then that investors and executives see ADCs as oncology’s next big jackpot. Pfizer’s $43 billion Seagen buy wasn’t just about acquiring a couple of drugs – it was a bet on owning the premier platform for ADC innovation (Seagen’s multiple ADC technology platforms and know-how), much as companies once vied to acquire key immunotherapy or gene therapy platforms.

The deal frenzy has also brought smaller biotech windfalls. When Immunomedics (maker of Trodelvy) was bought by Gilead for $21 billion in 2020 (dcatvci.org), it was a watershed moment that proved a single successful ADC can turn a mid-sized biotech into a massive buyout prize. More recently, platform-focused startups that haven’t yet commercialized a product have still commanded rich deal terms. Take Mersana Therapeutics, a Boston-based biotech with a novel ADC linker platform: it struck partnerships with the likes of Johnson & Johnson and Takeda over the years, and although its lead drug (upifitamab/rilsodotin for ovarian cancer) hit a safety snag in 2023, Mersana’s technology continues to draw interest.

Or consider Duality Biologics in Shanghai – it attracted BioNTech as a partner in 2023, with the German mRNA-vaccine maker paying $170 million upfront for two of Duality’s ADC candidates (one of which, a HER2-targeting ADC named DB-1303, is already in Phase II trials and has FDA fast-track status). Even early-stage toolmakers benefit: MacroGenics licensed its ADC platform to Synaffix; Oxford BioTherapeutics and others have carved out niches in antibody engineering for ADC use.

In short, money is gushing into ADCs at every level – from mega-mergers to licensing deals, from venture funding of startups to public-market enthusiasm for any company with “ADC” in its story. A specialized industry of contract manufacturers has also grown, since making ADCs is complex (requiring both biologics and high-potency chemical handling). The contract manufacturing market for ADCs was estimated at ~$1.8 billion in 2024 and projected to climb to ~$6.9 billion by 2035 (dcatvci.org). This suggests that not only drug developers but also service providers anticipate a sustained pipeline of ADC candidates needing production.

The Key Players: East, West, and in Between

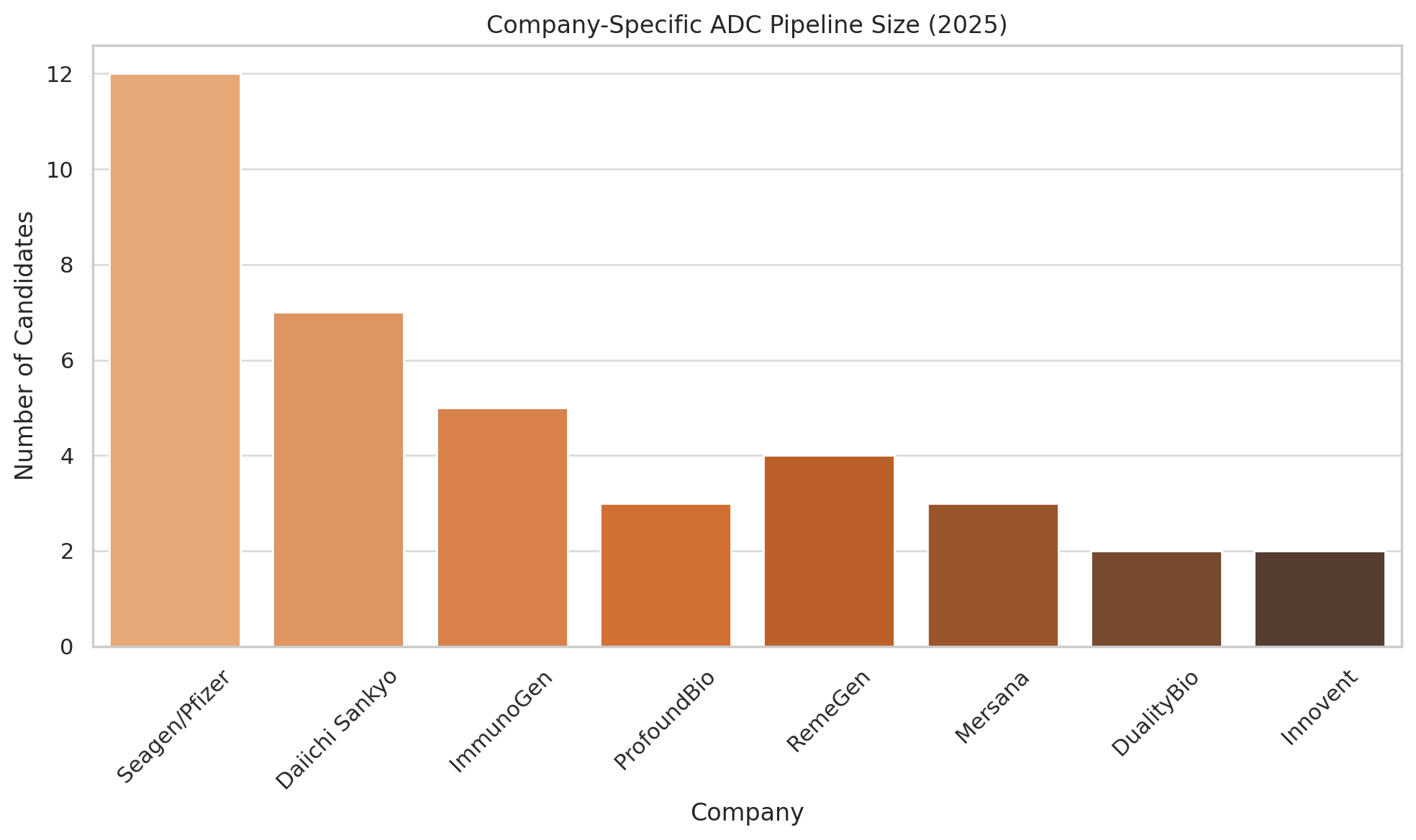

Which companies are poised to benefit most from this ADC ascendance? A handful of pioneers and power players dominate – some long-established in the field, others newer entrants with remarkable momentum.

Seagen (formerly Seattle Genetics)

Founded in 1998, Seagen essentially wrote the playbook for successful ADC development. It brought Adcetris to market in 2011 (for lymphomas) and helped validate the use of synthetic auristatin payloads (MMAE) and protease-cleavable linkers – innovations now widespread in ADC design. Seagen didn’t stop at Adcetris; it co-developed Padcev (enfortumab vedotin) for bladder cancer and Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin) for cervical cancer in partnership with Astellas and Genmab, respectively (dcatvci.org).

By 2022, Seagen had four approved ADCs (more than any other company at the time) and a deep pipeline (e.g. ladiratuzumab vedotin for breast cancer). Its expertise made it a coveted prize – resulting in Pfizer’s $43 billion acquisition. Now as part of Pfizer, Seagen’s scientific engine and product lineup give the pharma giant a commanding position in ADCs, with global reach to maximize these drugs’ potential.

Notably, Pfizer’s oncology portfolio pre-Seagen had no ADCs; post-merger, Pfizer boasts three top-selling ADCs (Adcetris, Padcev, Tivdak) right off the bat (dcatvci.org), plus the capability to launch new ones. Industry observers expect Pfizer/Seagen to push ADCs into new combinations (e.g. with immunotherapy) and possibly apply Seagen’s linker/payload tech to Pfizer’s own antibody assets. In many ways, Seagen’s journey from a small Seattle biotech to a $43 billion acquisition mirrors the maturation of the ADC field itself.

Daiichi Sankyo

This Japanese firm has emerged as an ADC powerhouse on the strength of its proprietary DXd linker-payload platform. Daiichi was a relative latecomer to biologics, but its researchers devised a tetrapeptide linker combined with a topoisomerase-1 inhibitor payload (an exatecan derivative) that proved to be a winning formula. The result was trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) – now marketed as Enhertu – which showed unprecedented efficacy in HER2-positive breast cancer, even in patients whom older drugs like Kadcyla could not cure. Enhertu’s success (2024 sales: $3.75 billion globally between Daiichi and partner AstraZeneca) instantly vaulted Daiichi into the big leagues of oncology.

The company has seven ADCs in clinical development, targeting HER2, HER3, TROP2, and other tumor markers. Its TROP2 ADC (datopotamab deruxtecan) just earned FDA approval in 2025 as Datroway, giving Daiichi/AZ a foothold in hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer. Daiichi’s ambition attracted Merck & Co., leading to the huge 2023 partnership for three earlier-stage ADCs (targeting HER3, B7-H3, and a novel antigen CDH6).

Daiichi is thus collaborating with not one but two global pharma giants (AZ and Merck) to bring its ADCs worldwide, while retaining manufacturing control and a strong presence in Japan. It’s a remarkable story of a mid-sized company leveraging innovation to punch above its weight. Daiichi’s ADC technology – including a newer class of PBD-based ADCs (with a potent DNA-damaging pyrrolobenzodiazepine payload, e.g. an anti-CLDN6 ADC in Phase I) – means it could continue to churn out candidates. If the DXd platform’s early promise holds across multiple cancers, Daiichi Sankyo stands to remain one of the most influential ADC developers well into the next decade.

ImmunoGen

An early trailblazer, ImmunoGen was founded in 1981 around the ADC concept long before it was fashionable. Its technology underpinned Kadcyla (ImmunoGen licensed its maytansinoid payload and linker to Genentech/Roche for that drug) – but ironically, ImmunoGen itself struggled for decades without a wholly owned success. That changed in 2022, when its drug Elahere (mirvetuximab soravtansine) won accelerated approval for a form of ovarian cancer. Elahere, targeting folate receptor-α on tumors, was the first ADC approved for ovarian malignancy and represented a validation of ImmunoGen’s sustained efforts. With Elahere’s launch looking positive and next-generation candidates in development (a higher-DAR folate-α ADC and an anti-CD123 ADC for rare leukemia), ImmunoGen became an attractive takeover target.

Sure enough, AbbVie swooped in and acquired ImmunoGen for $10.1 billion in early 2024 (dcatvci.org). For AbbVie, flush with cash from Humira and looking to bolster its oncology pipeline, this was a strategic buy – instantly giving it a marketed ADC (Elahere) and several pipeline shots, plus ImmunoGen’s underlying ADC platform. ImmunoGen’s journey highlights how persistence in an emerging technology can pay off handsomely. It also underscores consolidation in the sector: many of the standalone ADC-focused biotechs (ImmunoGen, Immunomedics, Seagen, etc.) have now been absorbed into big pharma, which could have both positive effects (more resources for development) and negative ones (less competition).

Mersana Therapeutics

While not yet a household name, Mersana typifies the new wave of ADC platform specialists. It developed a proprietary polymer linker system (Dolaflexin) allowing a higher drug-to-antibody ratio and controlled release of a novel DolaLock payload. The promise was to safely deliver more punch per antibody. Mersana’s lead candidate upifitamab (UpRi) showed early potential in ovarian cancer. However, the road turned rocky in 2023: the FDA placed partial holds on UpRi trials after some patients experienced severe bleeding and tragic fatalities (fiercebiotech.com).

Mersana’s stock plummeted ~60% on the news (clin.larvol.com), a stark reminder that ADCs carry unique risks – toxicity can emerge unexpectedly even in late-phase trials. The company’s follow-on programs (like XMT-1660 for breast cancer and XMT-2056, a novel Immunosynthen STING-agonist ADC) continue, and the FDA did lift a hold on one early trial after safety modifications (fiercebiotech.com).

But Mersana’s story sounds a caution: not every ADC platform will succeed, and even well-funded biotech can stumble if their “secret sauce” doesn’t translate into clinical safety. Nonetheless, big pharma has not written off Mersana – its past partnerships (with J&J, Takeda, GSK) suggest that if it can resolve safety issues, its higher payload approach could yet attract suitors or collaborators. In a field of high valuations, Mersana now represents a potential bargain with valuable IP, assuming it navigates the current setbacks.

The Chinese Contenders (RemeGen, DualityBio, MediLink, etc.)

We’ve touched on several in the context of the pipeline and deals, but it’s worth grouping them. RemeGen, with its disitamab vedotin success and a rich pipeline (including RC88, a BCMA-targeting ADC for multiple myeloma in trials), is sometimes called “China’s Seagen.” It went public in Hong Kong in 2020 and has drawn international partnerships (beyond Seagen, it collaborates with Janssen on other biologics). Duality Biologics, founded in 2020, quickly made waves by advancing two clinical ADCs (for HER2 and TROP2) and scoring the $170 million upfront deal with BioNTech (biospace.com).

Duality has since filed for a Hong Kong IPO, aiming to fund its growing pipeline (firstwordpharma.com).

MediLink Therapeutics, another Suzhou-based firm, developed a next-gen linker (TMALIN) and caught BioNTech’s eye as well – BioNTech paid $70 million upfront in 2023 for a HER3-directed ADC from MediLink, and in 2024 expanded the partnership with $25 million more upfront to access MediLink’s ADC platform for additional targets (fiercebiotech.com). These moves illustrate how BioNTech, flush with COVID-19 vaccine cash, is diversifying into ADCs via Chinese partners – effectively tapping into China’s innovation while providing global development muscle.

Meanwhile, other Chinese players like Kelun-Biotech, BioThera Solutions, Levena (Sorrento), and HTBA (HengRui) are all advancing ADC candidates, often in stealth until a deal shines a light on them. The Chinese ecosystem is marked by lots of academic-industry collaboration, fast follower tactics (e.g. developing analogous ADCs to known Western drugs, but also novel ones), and a willingness to license out assets to multinational companies to share risk and reward. This East-West synergy is a defining feature of the ADC landscape circa 2025 – it’s no longer “Silicon Valley biotech vs. Big Pharma,” but a complex web of partnerships spanning the globe.

BioNTech and friends

A special mention goes to BioNTech (Germany) – famous for mRNA vaccines – which has made a strategic pivot into ADCs and other cancer therapies after COVID. As noted, BioNTech struck deals with DualityBio and MediLink (fiercebiotech.com), signaling its belief that ADCs will complement its immunotherapy portfolio. Interestingly, BioNTech’s move echoes a broader trend: companies that thrived in one modality (e.g. mRNA vaccines) are now branching out into ADCs, recognizing cancer treatment likely requires a mix of modalities. BioNTech’s CEO Ugur Sahin even stated that the ADC class “might be an alternative to standard chemotherapy” in the future (biospace.com).

Given BioNTech’s deep pockets and scientific clout, its foray is worth watching. If its partnered ADCs succeed, BioNTech could become a major oncology player bridging East and West (since it’s co-developing Chinese-origin drugs for global markets). Similarly, other big firms traditionally outside oncology – such as Merck KGaA (which did a $1.4 billion ADC discovery deal with Caris Life Sciences in 2024) – are jumping on the ADC bandwagon.

In summary, the ADC field’s key players include a mix of established oncology giants (Pfizer, Roche, AstraZeneca, Gilead, etc., all of which now market ADCs), specialist biotech alumni (Seagen, ImmunoGen, Immunomedics – mostly acquired into bigger companies), platform biotechs (like Mersana, ADC Therapeutics, Sutro Biopharma, all developing enabling technologies or proprietary ADC twists), and a strong cast of Asian biotechs forging a new path.

The competitive dynamics are intense: for instance, multiple companies are developing ADCs against the same targets (there are at least half a dozen TROP2 ADCs in trials, chasing Trodelvy’s success, including candidates from Daiichi, AstraZeneca, Pfizer/Seagen, and several Chinese firms).

It’s reminiscent of the PD-1 inhibitor rush, where many entrants piled into an already crowded space – eventually, only a few winners (Keytruda, Opdivo) captured most of the value globally, while others (especially in China) carved out local niches. Will ADCs play out the same way, with an initial period of many players, followed by consolidation and a few dominant products per target? Or can multiple ADCs find sizable markets by differentiating in efficacy, safety or indicated cancer type? The answer will unfold in coming years, but for now a Darwinian contest is underway, likely to yield both spectacular triumphs and disappointing failures.

Hype vs. Reality: Are ADCs the Next PD-1 – or the Next Flash in the Pan?

With so much attention and money lavished on ADCs, a natural question arises: Are ADCs truly a paradigm shift in oncology, or is the excitement outrunning the evidence? The comparison to PD-1 inhibitors (the poster children of immunotherapy) is instructive. PD-1 checkpoint blockers went from first approval in 2014 to being a ~$45 billion market in 2023 (living.tech) – a transformative impact on cancer care, as these drugs now treat over a dozen cancer types and have produced unprecedented long-term remissions in some patients. No one doubts that immunotherapy changed the game.

ADCs, while much improved, have yet to demonstrate a similar breadth of impact. Most ADC approvals so far are in refractory settings – used after standard treatments fail – rather than front-line therapy.

For instance, Adcetris and Enhertu are moving earlier in treatment lines and expanding indications (Enhertu is now approved even for some lung cancers with HER2 mutations), but broadly speaking ADCs are still finding their optimal place in treatment protocols. One reason is safety: even the best ADCs carry toxicities that require careful management. Almost all ADCs cause some degree of bone marrow suppression (as their toxins inevitably hit some healthy cells), and certain agents have unique problems (e.g. ocular toxicity with MMAF payloads like in belantamab, liver toxicity with some earlier linkers).

The risk/benefit calculus therefore has to strongly favor an ADC to use it earlier in disease. As data matures, some ADCs are showing such benefit – for example, Enhertu in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer outperformed conventional chemo by such a margin that it’s rapidly becoming a standard of care. Similar hopes are placed on datopotamab deruxtecan (for lung and breast tumors) and others.

Another consideration is cost. ADCs are complex biologics to manufacture, often priced very high (many cost >$100,000 per course). Health systems that are already burdened by expensive cancer immunotherapies may balk at paying for ADCs on top. If every new ADC-approved cancer indication simply adds to therapy (rather than replacing a costly drug), the cumulative expense could be unsustainable. This economic reality could slow uptake unless clear value is demonstrated – for example, if an ADC provides cure-like outcomes in a setting where previously patients had no hope, the cost is justified. But if it offers only incremental benefit, payers might push back or restrict usage. The hype cycle in biotech tends to peak when expectations are sky-high. With ADCs, one can argue we are near that peak: dozens of companies jockeying, investment pouring in, and media touting “game-changing” potential. History reminds us that such cycles often lead to a shakeout.

Recall the CAR-T cell therapy boom around 2015–2017: revolutionary results in leukemia led to many startups and big investments, but commercial and logistical challenges limited CAR-T’s reach, and only a few companies (like Novartis and Gilead/Kite) have profited substantially, with others falling away. ADCs could see a similar winnowing. Already, we saw GSK’s withdrawal of Blenrep after initial fanfare, and the setback of ImmunoGen’s earlier trials (its first Phase III for an ovarian ADC failed in 2016, delaying progress until a better trial succeeded). Likewise, Daiichi and Merck had a reality check in 2025 when they withdrew a U.S. FDA application for patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-targeted) after Phase III data in lung cancer underwhelmed (dcatvci.org). That drug had been touted as a potential “next Enhertu,” but the results did not live up to the hype, illustrating that not every shiny ADC will fly straight.

Comparisons to prior oncology “trend cycles” are illuminating. With PD-1 inhibitors, the hype was largely justified – the drugs truly benefit broad patient populations and multiple companies succeeded (though Merck’s Keytruda emerged the clear leader). Targeted kinase inhibitors (e.g. EGFR, ALK inhibitors) had a boom in the 2000s; many were developed, but only a handful made a big impact while others fizzled due to resistance issues and competition. ADCs have aspects of both worlds: like targeted therapies, each ADC is very specific (to an antigen), meaning the addressable patient population might be limited by how many tumors express that target. If too many companies all target, say, HER3 or TROP2, eventually some will drop out or consolidate.

On the other hand, the modular nature of ADC technology (mix and match antibodies and payloads) means it could be a platform with wide applicability – similar to how PD-1 inhibitors became a backbone for many cancers, one could envision ADCs being used in many tumors, each time with a different antibody but using a handful of well-validated payload/linker systems. In that scenario, ADCs might become almost genericizable in concept: numerous drugs, but built on common scaffolds (for example, the vedotin platform, the deruxtecan platform, etc.). If that happens, a few platform owners (like Seagen/Pfizer or Daiichi) might license their tech broadly or dominate the market supply, while differentiation blurs.

One must also consider clinical trial outcomes in coming years. Many ADCs in Phase II/III now are aiming not just to win approval, but to outperform existing standard treatments. If a new ADC can beat a blockbuster like Keytruda or outdo standard chemo in a front-line setting, it will vault into mainstream use. Enhertu’s ongoing trials in early-stage breast cancer (adjuvant therapy) and lung cancer first-line are being closely watched – success there would expand ADC use enormously. Conversely, any unexpected safety fiasco can dampen enthusiasm.

The industry remembers how quickly enthusiasm for anti-CD28 superagonist antibodies evaporated after a notorious trial disaster in 2006, or how gene therapy’s early hype in the 1990s was reset by safety issues until the technology matured years later. So far, ADCs have had no catastrophic safety meltdown across the class, which is encouraging. Regulatory agencies are also now quite familiar with ADCs, which could smooth approval paths – but they are also vigilant, as shown by FDA’s Oncology Advisory Committee weighing risk/benefit carefully (in 2024 an FDA panel recommended limiting use of certain PD-1 inhibitors in early cancer settings due to trial failures, a reminder that confirmatory trials matter for ADCs as well).

At this juncture, the consensus in the oncology community is that ADCs are here to stay, but their ultimate impact is still being defined. They are likely complements to other therapies rather than replacements. For example, some of the most promising results come from combinations: ADCs paired with immunotherapy have produced synergistic effects (one striking example: combining Padcev with Keytruda led to significant improvements in first-line bladder cancer, prompting regulatory filings).

This suggests ADCs might integrate into multi-modal regimens – an era of “chemo-immuno-biology convergence,” where an ADC delivers the kill while a checkpoint inhibitor boosts immune response, yielding a one-two punch. If that becomes standard, ADCs will indeed mirror the PD-1 story by becoming part of first-line therapy for many cancers (just not as standalone agents, but as part of combos).

In assessing hype vs reality, one metric to watch is clinical utility: how much do ADCs improve survival or quality of life relative to alternatives? In some diseases, they have already made a huge difference (Hodgkin lymphoma survival jumped with Adcetris; HER2-positive breast cancer survival improved with Kadcyla and Enhertu; hard-to-treat triple-negative breast cancer got a new option with Trodelvy). In others, the jury is out.

But the pipeline breadth means if one ADC fails, another can take its place targeting a different antigen or using a better linker. The high level of redundancy and diversity in ADC R&D is actually a strength – it increases the odds that at least a few winners emerge for each cancer type. This is unlike the PD-1 space where all drugs hit the same target (PD-1/L1), making differentiation hard. With ADCs, not all eggs are in one target basket. So the field may avoid a uniform crash; instead, we may see a steady sorting into winners and losers.

Ultimately, ADCs represent a convergence of biologic and chemotherapeutic approaches – embodying the old concept of the magic bullet with modern biotech sophistication. The excitement is justified by real successes, and the financial investment, while arguably overheated, is accelerating the exploration of this modality. A correction or shakeout in coming years is possible, especially if some high-profile programs disappoint.

But even if hype cools, the foundational value of ADCs seems likely to endure. As one analyst quipped, ADCs are “too potent to ignore, and too specific to fail completely.” In a post-PD-1 world, oncologists are eager for new tools, and ADCs fill a niche by attacking tumors that don’t respond to immune therapies or traditional chemo alone. They are not a panacea – no single drug class is – but they add a powerful option to the arsenal.

In the next 5–10 years, we will find out just how transformative ADCs can be. Will they move into earlier treatment settings, potentially offering cures in combination regimens? Will they expand beyond oncology (early trials in diseases like lupus are flirting with targeted B-cell depletion via ADC)? And can the industry sustain reasonable pricing so that patients worldwide can benefit, not only those in wealthy healthcare systems? These questions remain open.

For now, what’s clear is that antibody–drug conjugates have moved from the fringes to center stage in pharma R&D. In the eyes of many researchers, they embody a marriage of two modalities – antibodies and chemo – “the best of both worlds.” After years of being overshadowed by immunotherapies, ADCs are finally having their moment in the spotlight. If science and prudence prevail alongside the enthusiasm, this reloaded magic bullet might indeed hit the bull’s-eye, changing the standard of care for numerous cancers and validating the hopes invested in it – not as a magical cure-all, but as a potent new chapter in the ongoing fight against cancer.

Member discussion