Royalties That Wake Up: How Change-of-Control Triggers Reshape Pharma Deal Economics

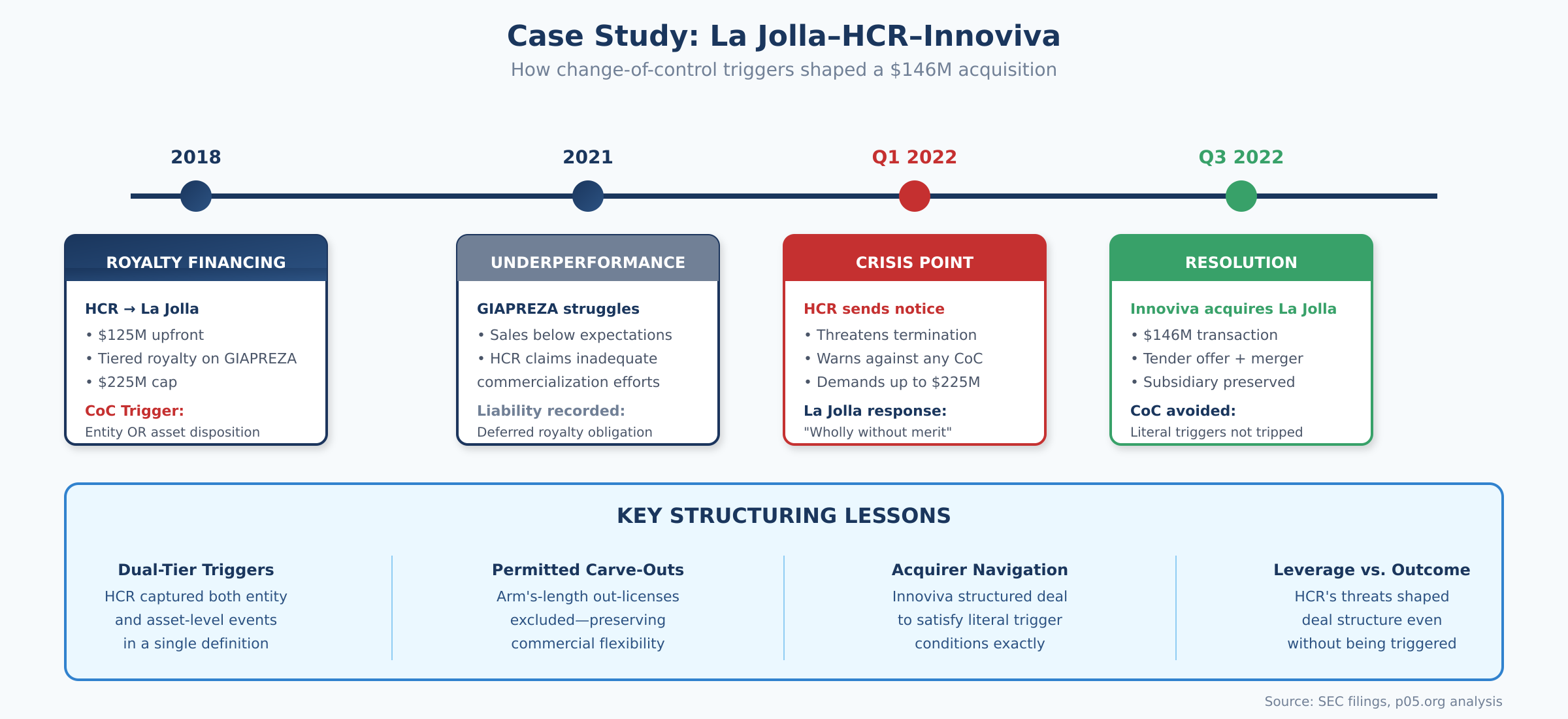

When Innoviva moved to acquire La Jolla Pharmaceutical in 2022, the transaction revealed a hidden tripwire that many biotech M&A participants only discover when it's too late. Healthcare Royalty Partners, which had provided La Jolla with $125 million in exchange for tiered royalties on GIAPREZA, sent an ominous notice: they were prepared to terminate the deal and demand immediate payment of up to $225 million if the acquisition compromised their position. La Jolla's management dismissed HCR's claims as "wholly without merit"—but then proceeded to structure the sale with surgical precision to avoid tripping the exact triggers HCR had negotiated years earlier.

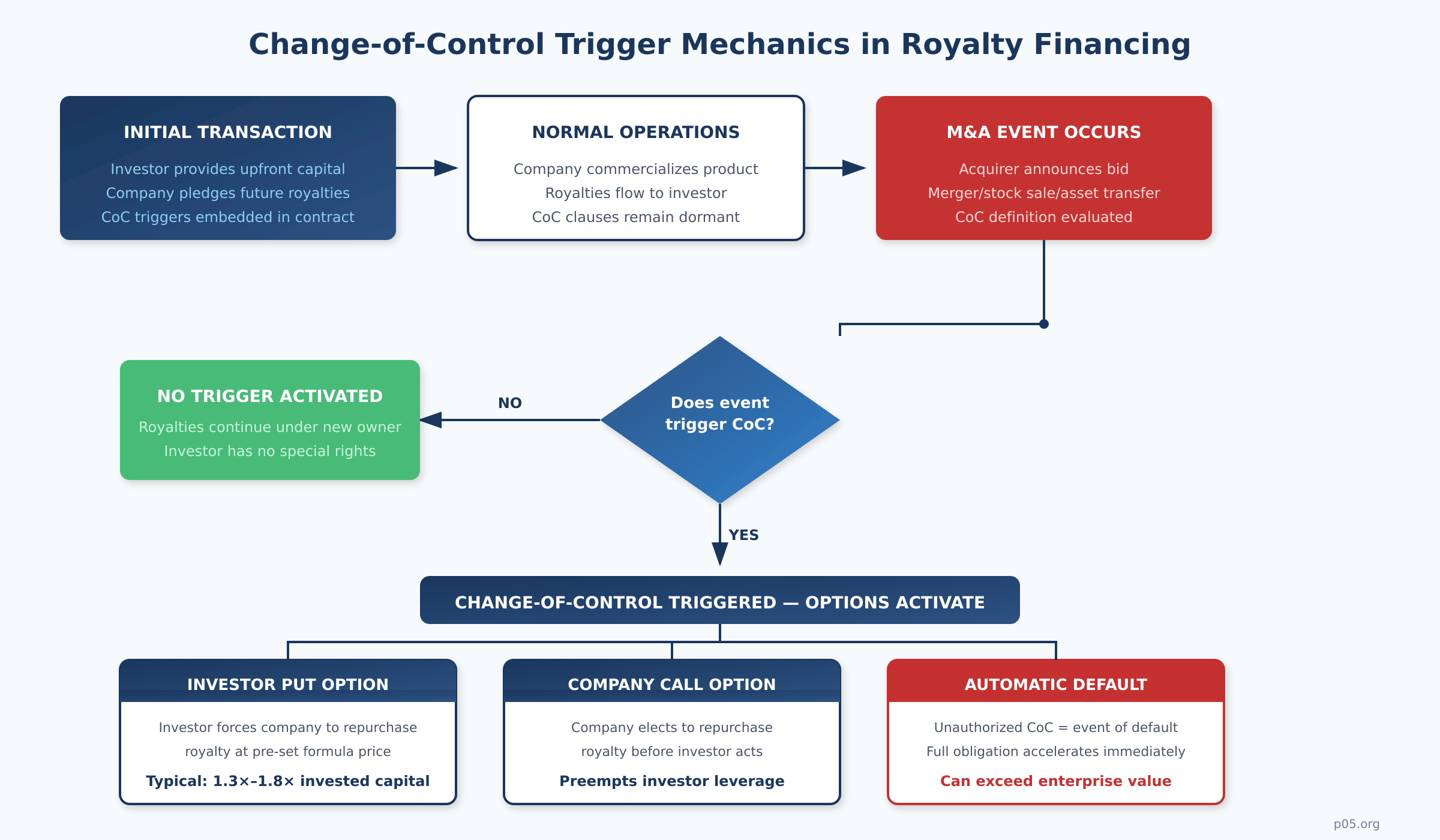

This is the world of change-of-control triggers in pharmaceutical royalty financing—contract clauses that lie dormant for years, only to spring awake when corporate earthquakes like mergers and acquisitions shake the ground beneath them. As the royalty monetization market has expanded beyond $15 billion in annual transaction volume, these provisions have evolved from boilerplate protections into sophisticated instruments that can determine whether a deal closes, at what price, and who captures the economic surplus.

The Strategic Logic: Why Triggers Exist

Before diving into mechanics, it's worth understanding why these clauses matter to both sides of a royalty transaction.

For the royalty investor, the concern is straightforward: they've paid substantial upfront capital in exchange for a share of future product revenues, predicated on a specific management team executing a specific commercial strategy. When a new owner arrives—whether a strategic acquirer, a private equity firm, or a competitor—that calculus may change dramatically. The new owner might deprioritize the product, change the sales strategy, or even discontinue it altogether if they have competing assets. The investor's carefully modeled return expectations could evaporate overnight.

For the company, change-of-control clauses represent a potential constraint on strategic optionality. Every biotech founder dreams of the exit—the acquisition by Big Pharma that rewards years of risk-taking. But if that exit triggers a $150 million payment to a royalty investor, the economics of the deal shift. Acquirers must price in that obligation, which often means shareholders receive less. In the extreme case, an onerous trigger might make the company effectively unattractive as an acquisition target.

The result is a negotiation over who bears the risk of corporate transformation, with the trigger mechanics determining how that risk is allocated.

Anatomy of a Trigger: What Counts as Change of Control

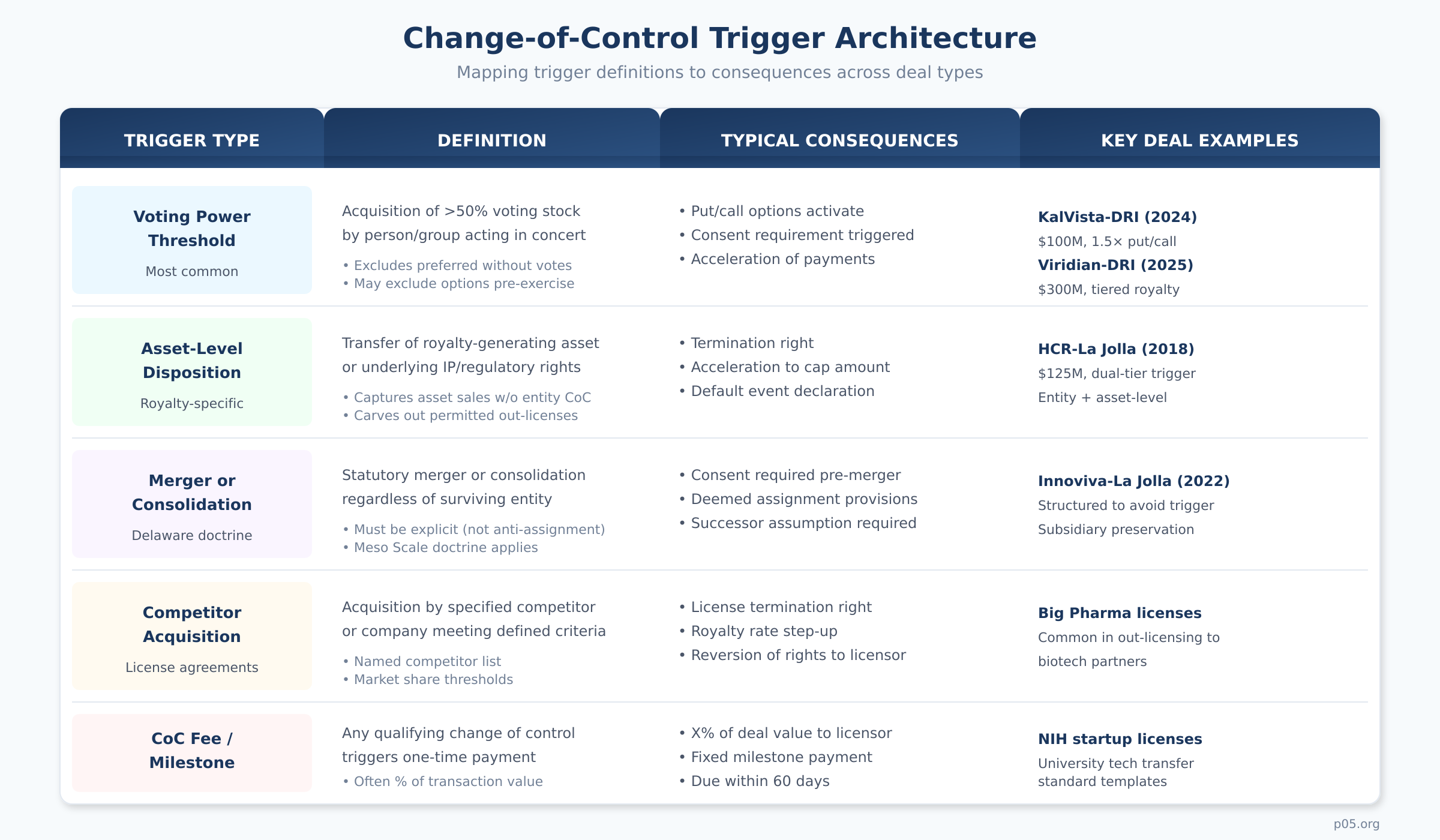

The simplest change-of-control definition—acquisition of more than 50% of voting securities—conceals layers of complexity that sophisticated negotiators spend months debating.

Voting Power vs. Economic Interest

Consider a company with 10 million common shares outstanding alongside convertible preferred stock and options. An acquirer purchasing 6 million common shares controls 60% of the voting power, yet holds only about 33% of the fully-diluted economic interest. Whether the trigger activates depends entirely on how the contract was drafted.

The KalVista-DRI Purchase and Sale Agreement illustrates the precision required. The definition references voting power of "Voting Stock," specifically defined as capital stock "having the power to vote generally for the election of directors." This seemingly narrow language excludes preferred shares without voting rights, convertible notes before conversion, and warrants before exercise—creating potential structuring opportunities for acquirers willing to accumulate positions through non-voting instruments.

Contracts must also specify how to count convertible securities and options. Three approaches dominate market practice. The actual basis approach counts convertibles only upon conversion and options only upon exercise, permitting accumulation through convertible instruments that individually don't trigger the threshold. The full dilution approach treats all convertible securities and in-the-money options as if already converted or exercised. The treasury stock method, borrowed from ASC 260-10-45, assumes proceeds from hypothetical option exercise are used to repurchase shares at market price, netting out the dilutive impact.

The difference matters. An investor holding 40% of common stock plus convertible preferred representing 25% on an as-converted basis would control 40% voting power under an actual-basis definition (no trigger) but 65% economic interest under full dilution (definite trigger).

The Dual-Tier Approach: Entity and Asset

The more consequential innovation in modern royalty financing has been the move toward asset-level triggers. The HCR-La Jolla agreement defined "Change of Control" to include not just entity-level ownership changes, but also any disposition of the GIAPREZA product itself—the patent rights, regulatory approvals, and commercial assets that generated the royalty stream.

Specifically, the agreement triggered upon either:

- La Jolla no longer directly owning 100% of the equity interests in La Jolla Pharma, LLC (the subsidiary holding the product), or

- La Jolla Pharma, LLC no longer directly owning the GIAPREZA product, including patent rights and regulatory approvals.

This dual-tier approach captured scenarios where a company might retain corporate independence while selling the crown jewels out from under the royalty investor. The second prong explicitly carved out permitted out-licensing on arm's-length terms—preserving commercial flexibility while preventing outright asset dispositions that would transfer the royalty stream's source to a third party.

Creeping Acquisitions and Measurement Timing

A threshold trigger that activates only upon "acquisition" may not capture gradual accumulation. Consider an investor who buys 15% in January, another 12% via private placement in March, 10% through convertible note conversion in June, and 14% through a tender offer in September. No single transaction exceeds 50%, but cumulative holdings cross the threshold.

Sophisticated contracts address this through point-in-time measurement (determining beneficial ownership on any measurement date, regardless of how accumulated), acquisition-based measurement (triggering on any acquisition that results in holdings exceeding the threshold), or rolling period aggregation (aggregating all acquisitions during any consecutive twelve-month period).

The choice matters more than it might seem. Point-in-time measurement provides the broadest protection for investors but requires constant monitoring. Acquisition-based measurement is simpler but can be gamed through small sequential purchases. Rolling periods offer a middle ground but create complex calculation obligations.

Delaware's Operation of Law Doctrine: The Loophole That Isn't

Every M&A lawyer knows the basic principle: under Delaware law, contracts transfer automatically through merger by "operation of law" without constituting an assignment. What fewer appreciate is how thoroughly Delaware courts have distinguished between assignment restrictions and change-of-control consequences.

In Meso Scale Diagnostics v. Roche Diagnostics, Vice Chancellor Laster articulated the doctrine with unusual clarity:

"Under established Delaware law, the surviving corporation in a merger, by virtue of the statutory vesting mechanism, becomes vested with all of the rights and property of the disappearing corporation automatically by operation of law.... The statutory vesting mechanism means that the surviving corporation is not an 'assignee' of the contract, because no act of assignment is necessary for the surviving corporation to obtain the rights under the contract."

The court then distinguished between contractual prohibitions on assignment and contractual provisions triggering consequences upon change of control:

"An anti-assignment provision, standing alone, does not provide any protection against a change of control accomplished by merger. To trigger consequences based on a merger or other change-of-control event, the parties must use language that specifically addresses those situations."

Subsequent cases have reinforced this principle. Cigna Health & Life Insurance Co. v. Audax Health Solutions (Del. Ch. 2019) applied Meso Scale to hold that general anti-assignment language did not prevent transfer of rights through merger. Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems v. Orbital ATK (Del. Ch. 2021) emphasized that contract language must "expressly address" mergers to restrict them; courts will not imply such restrictions.

The practical implication is unforgiving: if an investor wants the right to approve or cash out upon a merger, the agreement must say so explicitly. Generic anti-assignment language accomplishes nothing.

The Sidley Austin analysis recommends three formulations that survive the Meso Scale doctrine:

Consent Requirement Approach: "Neither party may assign, delegate, or transfer this Agreement or any rights or obligations hereunder, whether by merger, consolidation, operation of law, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the other party."

Deemed Assignment Approach: "For purposes of this Agreement, any merger, consolidation, or other business combination involving a party (whether or not such party is the surviving entity) shall be deemed an assignment of this Agreement by such party requiring consent."

Explicit Trigger Approach: "Upon the consummation of any merger, consolidation, or other business combination involving [Party], regardless of whether [Party] is the surviving entity, [Consequence] shall occur automatically without any further action required by either party."

Put/Call Economics: The Negotiated Exit

The most sophisticated royalty financings build in bilateral options that activate upon change of control, creating a framework for orderly resolution when M&A events occur.

The KalVista-DRI Structure

KalVista's 2024 deal with DRI Healthcare exemplifies the architecture. KalVista received $100 million upfront for future royalties on sebetralstat, with the following change-of-control provisions:

If a change-of-control event occurs before a specified date, DRI can exercise a put option forcing KalVista to repurchase the royalty at 1.5× the funded amount minus royalties already received. KalVista retains a mirror-image call option to repurchase at the same formula price if an acquisition is in play.

The economics are powerful. If an acquirer swoops in during Year 1 before any royalties have been paid, the put price equals $150 million—guaranteeing DRI at least a 50% return on capital deployed. This floor protects against scenarios where the acquisition premium accrues entirely to equity holders while the royalty investor is left holding an uncertain claim on future cash flows under new ownership.

How Timing Changes the Math

The put/call formula creates interesting dynamics as royalties accumulate:

Year 1 (pre-launch, $0 royalties paid): Put price = ($100M × 1.5) – $0 = $150M — Investor IRR: 50%

Year 2 (early commercial, $15M royalties paid): Put price = ($100M × 1.5) – $15M = $135M — Investor IRR: ~35%

Year 3 (mature commercial, $40M royalties paid): Put price = ($100M × 1.5) – $40M = $110M — Investor IRR: ~22%

Year 5 (peak sales, $80M royalties paid): Put price = ($100M × 1.5) – $80M = $70M — Investor IRR: ~15%

Year 7 (near cap, $130M royalties paid): Put price = ($100M × 1.5) – $130M = $20M — Investor IRR: ~11%

The declining put value means early change-of-control events strongly favor investor exercise, while late events may make it economically rational to simply continue receiving the royalty stream rather than triggering a buyout.

Market Practice on Multiples

Market practice has converged on put/call multiples in the 1.3× to 1.8× range for exercises within three to five years, calibrated to deliver mid-teens IRRs to the investor if triggered. The specific multiple reflects several negotiation dynamics:

- Product stage: Earlier-stage assets with higher uncertainty typically command higher multiples (1.6×–1.8×) to compensate for the investor's risk.

- Company leverage: Cash-strapped biotechs may concede higher multiples in exchange for more favorable upfront terms.

- Competitive dynamics: When multiple royalty investors are competing for a deal, multiples tend to compress.

- Expected M&A probability: Companies seen as likely acquisition targets may negotiate lower multiples as a condition of any financing.

The declining royalty rate structures common in recent deals add complexity. Viridian's 2025 financing with DRI featured rates stepping down from 7.5% on sales up to $600 million to effectively zero above $2 billion. This structure creates incentives for the investor to exercise put options early—while rates remain high—rather than waiting for the product to mature into lower-margin tiers where the put becomes less attractive than continuation.

The Automatic Trigger: When Options Become Obligations

Not all change-of-control consequences are optional. Some agreements treat an unsolicited change of control without investor consent as a default event, accelerating payment obligations that might otherwise have extended for decades.

HCR's agreement with La Jolla included precisely this feature. La Jolla was obligated not to undertake any change of control that would cause GIAPREZA's rights to slip away from the subsidiary generating the royalty. Violating this covenant would allow HCR to terminate the agreement and demand immediate payment of the cap amount—$225 million—less royalties already paid.

The royalty, in other words, could explode from a manageable ongoing obligation into a lump-sum liability that might exceed the enterprise value the acquirer was willing to pay. This is not hypothetical: in the La Jolla context, the $225 million potential acceleration represented roughly 1.5× the eventual acquisition price of $146 million.

The La Jolla Playbook: Navigating Around Triggers

Innoviva's structuring of the La Jolla acquisition demonstrated how these provisions constrain deal mechanics—and how sophisticated parties can navigate around them.

Rather than merging La Jolla Pharma, LLC out of existence or carving out the GIAPREZA asset, Innoviva structured a tender offer followed by a merger that preserved La Jolla as a wholly-owned subsidiary retaining 100% of the GIAPREZA rights. The literal trigger conditions remained unsatisfied:

- La Jolla still directly owned 100% of La Jolla Pharma, LLC (now as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Innoviva's acquisition vehicle)

- La Jolla Pharma, LLC still directly owned the GIAPREZA product

Whether HCR could have prevailed on a broader interpretation—arguing that ultimate beneficial ownership had changed even if the technical subsidiary structure remained—was never tested. The parties navigated around the clause rather than through it.

The La Jolla case offers four key lessons:

Dual-tier definitions provide comprehensive protection. By capturing both entity-level and asset-level changes, HCR ensured it would have leverage in almost any acquisition scenario—forcing the acquirer to either satisfy the literal conditions or negotiate directly with the investor.

Carve-outs preserve commercial flexibility. The explicit exclusion for arm's-length out-licensing meant La Jolla could pursue partnership strategies without inadvertently triggering the clause. This kind of precision drafting requires anticipating operational needs during the investment period.

Acquirers must diligence triggers carefully. Innoviva clearly understood the HCR agreement's trigger mechanics and structured its acquisition specifically to avoid activation. This required detailed legal analysis and may have constrained the deal structures Innoviva could consider.

Leverage operates even without activation. HCR's threats shaped the transaction even though no trigger was ultimately pulled. The presence of the clause—and HCR's demonstrated willingness to enforce it—influenced how Innoviva approached the deal.

The License Agreement Analog: Protecting the Upstream

While royalty financings protect investors seeking returns on capital, traditional license agreements deploy change-of-control triggers to protect licensors concerned about who will commercialize their intellectual property. The strategic logic differs, but the mechanical features overlap substantially.

University and Government Licenses

The U.S. National Institutes of Health startup license template includes a change-of-control royalty triggered upon licensee acquisition: X% of transaction value must be paid to NIH within 60 days. This ensures the original licensor participates in the upside when a licensee is acquired for a valuation built substantially on licensed technology.

University technology transfer offices have adopted similar provisions across the United States and Europe, addressing the recurring scenario where modest royalties negotiated with a cash-strapped startup fail to capture the windfall that materializes when Big Pharma acquires the licensee at a premium. The typical structure involves a one-time payment of 1%–5% of acquisition consideration, payable within 30–90 days of closing.

These change-of-control fees are essentially pre-negotiated M&A bonuses for the licensor, reflecting the reality that a small biotech's acquisition often delivers windfall value based on the licensed IP.

Competitor Acquisition Provisions

The concern cutting the other direction is equally real. Licensors worry that a small biotech licensee might be acquired by a competitor with overlapping products, reducing focus on the licensed drug or creating an unwanted relationship with a strategic rival.

Many IP license contracts therefore include provisions allowing termination or renegotiation if the licensee is acquired by specified competitors. These provisions function as poison pills or bargaining chips in M&A negotiations—a competitor considering acquiring the licensee must factor in the risk that the license for a prized drug could be yanked away or renegotiated on less favorable terms.

Some agreements specify automatic consequences upon competitor acquisition: royalty rate step-ups (e.g., rates double for sales by a top-10 pharma acquirer), reversion of rights to the licensor, or termination with a wind-down period. Others grant the licensor a consent right, creating leverage without automatically voiding the agreement.

The logic is that if a rival pharma ends up owning the product, the original licensor should get additional reward—or have the opportunity to terminate and reclaim the asset. These provisions must be carefully calibrated: too punitive, and they scare off partnership opportunities for the biotech; too lenient, and the original licensor might lose strategic control.

Accounting Treatment: The Liability That Looks Like Revenue

The $125 million La Jolla received from HCR might sound like a sale—the company monetized future royalty streams for upfront cash. But under U.S. GAAP, the transaction was recorded as a deferred royalty liability, not revenue. The accounting treatment reveals the economic substance: this was financing secured by product cash flows, not a completed sale of an asset.

US GAAP Treatment

Each quarter, La Jolla recognized non-cash interest expense on the liability and reduced the carrying amount by royalties paid to HCR. The effective interest method spread the implicit financing cost over the expected life of the arrangement, calibrated to the $225 million cap and the projected payment schedule through 2031.

The logic is straightforward: La Jolla retained primary responsibility for commercializing the drug and generating the sales that would produce royalty payments. Until HCR received its full return (or the cap was reached), the earnings process wasn't complete. The cash received was therefore an advance—a liability to be satisfied through future cash flows—rather than realized revenue.

Embedded Derivatives from Trigger Provisions

Change-of-control triggers added another layer of complexity. La Jolla's agreement included provisions that would accelerate payments if commercialization efforts fell short—essentially, HCR could demand up to $225 million rather than the base $125 million if La Jolla failed to use sufficient efforts.

Under ASC 815, these contingent payment provisions constituted embedded derivatives requiring separate fair value measurement. La Jolla had to estimate the probability of triggering the acceleration and recognize fair value for the derivative representing HCR's right to enhanced payments.

La Jolla disclosed that it evaluated these triggers each reporting period and concluded their fair value was immaterial—but the accounting requirement meant ongoing monitoring and disclosure of the potential exposure.

IFRS Convergence

IFRS reaches the same destination through slightly different reasoning. Under IFRS 15, when a company receives upfront cash but retains primary responsibility for the product and must use future revenues to satisfy the investor, the arrangement constitutes financing rather than revenue recognition. The proceeds appear as financial liability; interest expense accrues over time.

One IFRS wrinkle involves classification under IFRS 9: a royalty-linked payment stream might technically fail the "solely payments of principal and interest" (SPPI) test, since payments vary with sales rather than a fixed rate. If strictly interpreted, that could force fair value measurement through P&L rather than amortized cost. In practice, most companies using IFRS have found ways to treat royalty monetizations similarly to US GAAP by estimating future cash flows and applying an effective interest rate.

The Bottom Line for Financial Analysis

For analysts evaluating companies with royalty monetization transactions:

- Cash is debt, not revenue. The upfront payment appears on the balance sheet as liability, not as an immediate boost to earnings.

- Interest expense accrues over time. The income statement shows non-cash interest expense representing the implicit financing cost.

- Change-of-control scenarios require modeling. If early M&A triggers a buyout at formula price, the company recognizes a gain or loss equal to the difference between carrying value and payoff amount.

- Treat these as debt for valuation purposes. Enterprise value calculations should include royalty financing liabilities, since they represent claims on future cash flows functionally equivalent to secured borrowing.

Investors and analysts in the biotech sector have grown accustomed to adjusting for these liabilities. The largest royalty monetizations—some exceeding $1 billion—can represent significant portions of a company's capital structure and must be understood to properly evaluate equity value.

Tax Structuring: Character Matters

Whether the upfront payment constitutes a loan or income for tax purposes determines immediate recognition versus deferral—a binary outcome with potentially massive consequences.

The Company Perspective

Most U.S. biotech firms structure transactions to achieve loan treatment for tax purposes, avoiding upfront taxation on the cash received and preserving deductibility for royalty payments flowing to the investor.

Key factors include risk allocation (if the investor has no guaranteed return and can only be paid from product sales, the IRS may view the transaction as a sale of future rights rather than a loan), make-whole provisions (clauses ensuring minimum returns add debt-like characteristics that support loan treatment), and the presence of caps (payment caps establish a defined principal amount that strengthens the financing characterization).

Companies often seek private letter rulings or rely on established case law to confirm treatment as financing. The stakes are substantial: a transaction recharacterized as an asset sale could trigger immediate recognition of the full upfront amount as income, with royalty payments treated as non-deductible distributions rather than interest.

Cross-Border Complications

In cross-border situations—common given that major royalty investors operate globally—withholding tax becomes critical.

Royalty payments to a foreign investor may attract withholding tax as royalties under applicable tax treaties (typically 0%–10% depending on the treaty). Characterization as interest might permit access to portfolio interest exemptions with zero withholding. The legal form and documentation influence how foreign tax authorities classify the payments.

Many royalty financings route cash flows through special purpose vehicles in tax-efficient jurisdictions—typically Luxembourg, Ireland, or Netherlands—to minimize withholding leakage. The structure must be substantiated with real economic activity to survive transfer pricing scrutiny.

Change-of-Control Buyout Treatment

The change-of-control buyout introduces additional character questions:

For the investor: If DRI exercises its put option and receives 1.5× principal, the transaction likely constitutes a sale by DRI of its financial asset back to KalVista. The gain (0.5× principal in this example) may qualify as capital gain rather than ordinary income, depending on DRI's tax status and holding period.

For the company: The payout might be treated as a termination payment yielding deductible expense analogous to prepaying debt with a premium. Alternatively, if the payment is made by the acquirer rather than the target, it may be capitalized as part of acquisition cost.

For the acquirer: Sophisticated acquirers often prefer to pay off royalty obligations and capitalize the cost, enabling amortization over 15 years under Section 197 rather than letting the liability continue hitting future earnings as an expense. This preference drives tri-party negotiations where target, buyer, and royalty holder agree that at closing the buyer will buy out the royalty for a negotiated price, with the acquisition consideration adjusted accordingly.

The Mallinckrodt Warning: Structure Determines Survival

The most cautionary tale for royalty investors emerged from Mallinckrodt's 2020 bankruptcy. Decades earlier, Mallinckrodt had purchased the rights to Acthar Gel from a seller agreeing to pay a 1% perpetual royalty. The seller did not retain ownership or a license—it was an outright sale with only a security interest securing the upfront payment, not the ongoing royalty stream.

When Mallinckrodt filed for bankruptcy, the company moved to shed the royalty as an unsecured claim. The Third Circuit's 2023 ruling in In re Mallinckrodt allowed exactly that. Once the seller had transferred the asset, the royalty was merely a debt—and unsecured debts can be wiped out in bankruptcy.

The structural lesson is stark. Had the original seller retained a right to rescind the license upon payment default, or a reversion of the IP if royalties ceased, the transaction would have constituted an executory contract that Mallinckrodt could not so easily discard.

Modern royalty financings have internalized this precedent, typically granting investors:

- Second-priority security interests in the underlying IP, ensuring the investor has a secured claim that survives bankruptcy

- Conditional assignments that spring if payment obligations are not met, effectively giving the investor the right to take ownership of the asset

- Termination rights upon bankruptcy filing, allowing the investor to accelerate obligations before the automatic stay prevents collection

Change-of-control triggers serve a related protective function. They can force a buyout before a distressed company's obligations get discharged or diluted in restructuring, converting a potentially vulnerable ongoing stream into a crystallized claim that commands priority attention in any transaction.

Jurisdictional Variations: The Global Landscape

While the United States has developed the most active market for royalty monetization and the most extensive litigation interpreting change-of-control provisions, the principles translate across major pharmaceutical markets with important local variations.

Japan

Under Japanese law, the effect of merger on contract obligations remains less settled than in Delaware. Japanese commercial contracts almost universally prohibit assignment without consent, but whether merger constitutes assignment is unclear absent explicit contractual language. Legal scholars debate the issue, and with no definitive precedent, practitioners assume the safest course is treating mergers as triggering events requiring consent.

This means Japanese deals explicitly address change of control through contractual definition rather than relying on default law. The practical result resembles U.S. practice, but the drafting burden is heavier.

One cultural aspect: Japanese firms are sometimes more reluctant to terminate agreements outright even if a trigger occurs, preferring to renegotiate. Clauses may provide for "good faith discussions" before termination rights are exercised.

South Korea

South Korean contract law, heavily influenced by common law, permits change-of-control provisions but has generated little local litigation interpreting them. Korean biotechs engaged in global partnerships typically include consent requirements modeled on U.S. and European templates, reflecting the cross-border nature of most significant licensing arrangements.

Royalty financings are less common in Korea (companies more often use straight debt or equity financing), but as Korean biotechs increasingly seek non-dilutive funding, we expect adoption of global market structures including change-of-control triggers.

European Union

The European Union adds a competition law overlay absent in most other jurisdictions. While change-of-control provisions are generally viewed as legitimate protection of the licensor's interest in choosing its partners, a clause that automatically terminates a license upon acquisition by a dominant market participant could theoretically draw antitrust scrutiny if it produces anticompetitive effects.

In practice, no major EU case has struck down a change-of-control clause, but sophisticated drafters remain attentive to the possibility. The analysis turns on whether the provision serves a legitimate commercial interest (protecting licensor's relationship with specific partners) versus functioning as an anticompetitive restraint (foreclosing market access).

Some European jurisdictions also require registration of certain interests. In Italy, for example, ensuring a license can be enforced against a successor may require registration in the patent register. Germany has nuanced rules about encumbrances on patents that might affect how a royalty interest survives insolvency.

Recent Market Transactions: 2024–2025

The recent period has produced increasingly complex structures reflecting the maturation of the royalty financing market.

Revolution Medicines–Royalty Pharma (June 2025)

Revolution Medicines' $2 billion financing with Royalty Pharma combined a synthetic royalty of up to $1.25 billion with a $750 million senior secured loan—a hybrid structure requiring coordinated change-of-control provisions across both instruments.

The intercreditor agreement established priority and coordination:

- Senior lender claims proceeds first in any change-of-control scenario

- Synthetic royalty holder enters standstill during any senior cure period

- Excess proceeds share pro rata after senior satisfaction

- Senior lender controls enforcement actions to prevent conflicting remedies

A change-of-control triggering both instruments simultaneously could generate buyout obligations exceeding $1.6 billion:

- Senior loan prepayment: $500 million (illustrative)

- Prepayment premium (2%): $10 million

- Synthetic royalty put: ($800M funded × 1.5×) – $100M royalties = $1.1 billion

Total potential CoC buyout cost: $1.61 billion

Viridian Therapeutics–DRI Healthcare (2025)

Viridian's deal with DRI Healthcare introduced a declining royalty rate structure:

- Sales $0–$600M: 7.5% royalty rate

- Sales $600M–$900M: 0.8% royalty rate

- Sales $900M–$2B: 0.25% royalty rate

- Sales >$2B: 0% royalty rate

This structure creates interesting change-of-control dynamics. The blended royalty rate declines rapidly as sales grow, from 7.5% in early tiers to under 2% at $3 billion in annual sales. The investor's incentive is to exercise put options early—while rates remain high—rather than waiting for the product to mature into lower-margin tiers.

At $200 million in annual sales (7.5% blended rate), the put captures maximum value. At $3 billion in annual sales (1.8% blended rate), the put may be less attractive than simply continuing the royalty stream, since the formula-based buyout price provides limited premium over discounted future cash flows.

XOMA–Takeda Portfolio Agreement (2025)

XOMA's agreement with Takeda involves a portfolio of nine development-stage programs, raising interesting questions about how change-of-control provisions apply to diversified royalty interests:

- Does single asset divestiture trigger CoC? Typically no, unless the divested asset represents a material portion (often defined as >25%) of portfolio value.

- Does third-party acquisition of a portfolio company trigger? Yes, if the acquisition exceeds the ownership threshold, but the consequences may be prorated to that company's contribution.

- Does Takeda corporate CoC trigger? Generally yes, with obligations transferring to the successor through assumption agreements.

- How is portfolio put price calculated? Options include aggregate formula (treating the portfolio as a single asset), asset-by-asset calculation (potentially complex), or value-weighted approaches.

Strategic Implications: Playing the Long Game

For Licensors and Royalty Sellers

Change-of-control triggers function as both protective shields and offensive bargaining chips. A biotech licensing drug candidates should insist on approval rights if ownership passes to a new party—especially one that might be a competitor or lack development commitment.

Some provisions specify that change of control automatically triggers milestone payments, effectively allowing the licensor to cash in as though development succeeded regardless of actual progress. This deters casual flipping of licenses while ensuring participation in upside that might otherwise flow entirely to equity investors in a sale.

The counterargument from licensees is equally valid: overly aggressive change-of-control provisions may scare off potential acquirers and depress valuations, undermining the very exit that represents the typical biotech endgame.

The compromise often reached is a tiered structure—higher payments if the company is sold within two years of licensing (when little value has been added by the licensee), declining fees for sales after significant development progress. The licensor is protected from immediate flips while the licensee avoids undue penalty for legitimate later exits.

For Companies Carrying Royalty Obligations

Any biotech that has pledged royalties in financing knows that acquisition economics must account for the cost of satisfying the investor. This factor influences minimum acceptable sale prices and may drive decisions to refinance or restructure royalty arrangements before actively seeking a buyer.

Royalty financing agreements often include windows during which the company can repurchase the royalty at a set multiple. One strategic use: if the company expects to be acquired, it might trigger the buyback to avoid giving the investor leverage in negotiations (since an acquirer might otherwise negotiate directly with the investor, potentially extracting more favorable terms).

However, these early call options may themselves be contingent on events like an impending change of control or a certain date, so timing is everything.

For Acquirers

Every acquirer should diligence change-of-control provisions as carefully as it diligences the target's IP portfolio. Key questions include:

- What triggers exist? Map every license, royalty agreement, and financing arrangement to identify potential activation events.

- What are the consequences? For each trigger, understand whether the consequence is consent requirement, put/call option, automatic payment, or termination right.

- What is the cost? Model the maximum payout under each triggered provision to understand worst-case acquisition economics.

- Can we structure around the triggers? As Innoviva demonstrated with La Jolla, creative deal structuring can sometimes satisfy literal trigger conditions while still achieving economic objectives.

- Should we negotiate directly with counterparties? In some cases, preemptive settlement with royalty holders or licensors—even at a premium—may be cheaper than facing uncertain trigger activation.

Drafting Principles: Lessons from the Frontlines

The accumulated experience of royalty financing transactions suggests several principles for practitioners structuring these arrangements:

Define triggers with precision. Explicitly enumerate what transactions constitute change of control—mergers, stock sales, asset sales of the product line—and carve out internal reorganizations and transfers to affiliates. In Japan and Korea, resolve default law ambiguity through contractual definition rather than relying on uncertain judicial interpretation.

Distinguish between consent requirements and automatic consequences. Consent provisions offer flexibility—parties can always negotiate waivers when circumstances warrant. Automatic termination or payment acceleration provides leverage but eliminates room for adaptation. Tailor the approach to strategic objectives.

Calibrate buyout formulas to anticipated deal economics. Put/call multiples in the 1.3× to 1.8× range within three to five years typically approximate mid-teens IRRs for the investor if triggered—adequate compensation for lost upside without creating multiples so high that no acquirer would ever pay them.

Model accounting implications upfront. Understand that royalty monetization generates liability rather than one-time revenue, and project different scenarios—no M&A versus early M&A—for disclosure purposes.

Consider bankruptcy protection. In light of Mallinckrodt, ensure the investor has security interests or contractual protections (termination rights, conditional assignments) that survive bankruptcy proceedings.

Address interaction with other obligations. When royalty financing coexists with senior debt, intercreditor agreements should coordinate change-of-control consequences to prevent conflicting remedies or priority disputes.

Conclusion: The View from 30,000 Feet

Change-of-control triggers in royalty financing reflect a fundamental tension in pharmaceutical deal-making. Capital providers want protection against the risk that their carefully structured returns will be compromised when new owners with different priorities appear. Companies want flexibility to pursue strategic options—including sale—without crippling payoff obligations. Licensors want assurance that relationships forged with specific partners will not be involuntarily transferred to competitors or acquirers lacking development commitment.

The result is contractual architecture of increasing sophistication, where billions of dollars turn on the precise formulation of trigger definitions and the mechanics of put/call economics.

As pharmaceutical M&A volumes continue at historically elevated levels and the royalty monetization market expands beyond its traditional boundaries, the once-arcane world of change-of-control provisions has moved from boilerplate to center stage. A royalty agreement may lie quietly in the footnotes of financial statements for years, but when an acquisition announcement hits, dormant clauses can suddenly roar to life—much to the delight of one party and the dismay of another.

The lesson for dealmakers is eternal: read the fine print. Today's financing or partnership could be tomorrow's pay-out clause. Those who structure agreements astutely—as HCR did with La Jolla—can turn an acquisition into a lucrative exit. Those who fail to anticipate the scenarios—as Acthar's seller discovered in Mallinckrodt's bankruptcy—may find their claims discharged and their expectations of perpetual royalties extinguished.

In the end, royalties, like certain domesticated felines, have a way of waking up unexpectedly. The prudent course is to know exactly what will rouse them from slumber—before the merger announcement lands.

All information in this report was accurate as of the research date and is derived from publicly available sources including company press releases, SEC filings, regulatory announcements, and financial news reporting. Information may have changed since publication. This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment, legal, or financial advice.

Member discussion