Royalty Finance Without the Ornament: How Charities, Lawyers and Biotech Veterans Actually Use It

We held our first royalty-financing event in London during the Jefferies Healthcare Conference, a meeting better known for quick negotiations than for slow examinations of cash-flow structures. The contrast worked. While the main conference discussed valuation cycles, clinical inflection points and the temperament of public markets, our session attracted people who focus on the financial plumbing beneath drug development.

Our speakers represented three distinct vantage points.

Tony Hickson, Chief Business Officer of Cancer Research Horizons, brought the charitable and translational perspective.

Richard Gervase, Chair of Mintz’s Royalty & Revenue Interest Financing Transactions practice, outlined the legal and structural realities of the market.

Bodo Marr, former Morphosys executive, provided the operator’s view of using royalties under actual corporate pressure.

Together, they demonstrated that royalty finance is no longer a niche curiosity but a practical instrument for organisations that need capital when other channels stall.

Charities Behaving Like Early-Stage Investors

Cancer Research Horizons, functions much like a translational investor embedded within a research charity. It manages CRUK’s intellectual property portfolio, builds spinouts and operates drug-discovery units that have expanded over several decades. The organisation channeled hundreds of millions of pounds into research and directs a portion of donor contributions into early-stage ventures.

Its seed-stage fund, small in absolute terms but precise in mandate, deploys capital to bridge very early companies to the stage where institutional investors become willing to engage. It does not chase IRR targets; its purpose is to reduce the volume of scientifically credible assets that fail simply because no one will fund the first two steps.

The model fits within UK charity law, which allows mission-aligned investments. Hickson notes that donors increasingly expect their money to circulate through translational activities rather than sit in long-lived infrastructure. Other charities, observing the same shift, are beginning to construct their own translational units.

The Legal Architecture Behind Royalty Streams

Richard Gervase, who leads Mintz’s practice in royalty and revenue-interest financing, explained why these structures persist and why investors still pursue them despite their complexity. The mechanism remains straightforward: a company commits to a future revenue stream, and an investor advances capital today in exchange for the right to those payments over a long horizon.

The legal foundations are older than biotechnology. Royalties originated in extraction industries, migrated into oil and gas, and eventually entered biopharma when licensing deals became common. Most activity still occurs in the United States, where deeper licensing markets, larger deal volumes and specialized funds have produced a more consistent ecosystem. Europe remains more bespoke and less predictable.

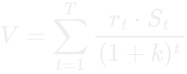

The underlying mathematics has not changed:

The real work lies in estimating k, a discount factor that must absorb biological uncertainty, regulatory timelines, payer behaviour and commercial volatility. Investors increasingly apply this model earlier in the pipeline, particularly to platform companies with multiple derivable drug candidates. This shift pushes royalties toward structured venture rather than late-stage project finance.

For Operators, Royalties Are a Means of Survival

Bodo Marr’s contribution offered the most grounded perspective. As a former Morphosys executive, he illustrated how a mid-sized biotech uses royalties when other forms of capital become uncooperative. Morphosys identified promising Phase 1 and Phase 2 assets but lacked the balance-sheet capacity to acquire them outright. Public markets did not offer attractive terms, and issuing more equity risked excessive dilution.

Royalty financing, combined with debt and contingent structures, provided a workable solution. The company ultimately raised more than a billion euros, enabling it to complete an acquisition, extend its pipeline and shift its risk profile. Marr’s example shows that royalties are no longer confined to monetising late-stage assets with predictable cash flows. They now operate as instruments for corporate financial engineering at decisive moments.

A Convergence of Constraints

The three perspectives converge on several points:

- Charities want capital tools that allow them to recycle donor funds into translational research.

- Investors want long-duration contractual cash flows during a period of unstable public markets and inconsistent monetary policy.

- Companies want structured non-dilutive capital that banks will not provide and equity markets will not reward.

Royalties sit in the overlap. They do not resolve scientific uncertainty but redistribute it across parties who can tolerate different types of risk.

A Market Still Missing Benchmarks

Despite their importance, royalty transactions remain difficult to compare. Deal structures vary widely by clinical stage, underlying licence design, step-down rate architecture, milestone layers, counterparty type and therapeutic area. Public disclosures are inconsistent. No shared market standard exists.

This informational vacuum leads to predictable distortions. Investors price idiosyncratically. Companies negotiate without reference points. Charities operate without clear comparators. Royalty finance possesses all the traits of an emerging asset class—except transparent data.

Building Comparables Like a Bloomberg Terminal for Drug Royalties

Capital for Cures is addressing this gap by building a benchmarking and comparable-analysis platform for royalty transactions. The intention is to create a tool that functions much like a Bloomberg terminal for royalty finance: structured datasets, normalised terms, valuation ranges, peer groups and analytical modules that transform a scattered market into something resembling an intelligible dataset.

The goal is analytical clarity. Investors can test the reasonableness of discount rates. Charities can benchmark their deals. Operators can understand likely structures and ranges at different development stages. If royalty finance is to mature, it requires shared standards rather than folklore.

An Invitation

Our session at Jefferies was our first event dedicated entirely to royalty finance. It demonstrated that the field benefits from direct discussion without theatrics and that many of you want a space where these transactions can be examined with precision rather than mystique.

We will continue both sides of the effort: expanding the benchmarking platform and hosting more sessions where investors, operators and translational groups can speak candidly about structured capital.

If you want to contribute data, invest, follow the platform’s development or join future meetings, you are welcome. The aim is straightforward: build a clearer, data-driven understanding of royalty finance and the role it now plays in drug development.

Member discussion