Royalty Financing Rescues Biopharma: A H1 2025 Global Analysis

The first half of 2025 saw an unprecedented surge in royalty-based financings and structured revenue deals across the biopharmaceutical sector. Faced with a bleak equity market and tightening credit, drug developers from Boston to Basel turned to royalty monetization as a lifeline. In the span of January to June 2025, biopharma companies struck royalty and revenue-interest deals totaling approximately $3.4 billion in disclosed upfront volume, spanning markets from the United States and Europe to Asia.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of these H1 2025 transactions – how they are structured, which therapeutic areas led the charge, and what trends are shaping this alternative financing boom.

The Rise of Royalty Deals in a Funding Squeeze

By 2025, royalty financings had moved from niche to mainstream. In the wake of a prolonged biotech bear market, companies large and small embraced non-dilutive funding by selling rights to future drug revenues. According to industry analysts, the number of royalty-based deals has grown “exponentially” in recent years as traditional funding sources dried up. The twin drivers are clear: biotech stock valuations have sagged, making equity raises painfully dilutive, and rising interest rates have rendered loans costlier. As one advisor noted, when a biotech CFO needs a few hundred million dollars to launch a drug but sees their stock price in the gutter, royalty monetization starts to look attractive. In short, companies are mortgaging slices of future drug sales for cash today, sidestepping the unfavorable terms of public markets and debt .

Investors, for their part, have eagerly stepped in to fill the void. A new breed of specialist funds and private-credit firms honed in on life sciences are structuring innovative royalty transactions, having become adept at evaluating drug risks better than generic lenders. “It’s not a space you can dabble in,” notes Peter Schwartz of CreditSights, emphasizing that understanding a drug’s science and market is crucial in these deals . But for those with expertise, royalty financings offer a return uncorrelated to stock market swings – a bet on a drug’s success rather than the issuing company’s share price .

One consulting firm found that from 2018–2022 the total value of royalty financings grew at a 45% compound annual rate, outpacing equity raises. That resiliency against macroeconomic headwinds is precisely why 2025’s turbulent market has catalyzed a boom in such deals.

Table 1 – Selected Royalty/Revenue-Interest Deals in H1 2025 (Source: company releases)

| Company (Country) | Asset (Indication) | Investor(s) | Deal Structure | Upfront / Total Amount (USD) | Stage (H1 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genfit (France) | Elafibranor – PBC (rare liver disease) | HealthCare Royalty (HCRx) | Capped royalty sale on Ipsen deal | €130M upfront (±$140M); up to €185M total | Commercial (FDA approved 2024) |

| Heidelberg Pharma (Germany) | TLX250-CDx – renal cancer imaging | HCRx | Royalty financing (amended) | $20M immediate; up to $90M total | Phase 3 (FDA filing 2025) |

| RegenXBio (USA) | Zolgensma royalties + gene therapy pipeline | HCRx | Royalty-backed notes (“royalty bond”) | $150M upfront; up to $250M total | Mixed (marketed & Phase 3) |

| Revolution Medicines (USA) | Daraxonrasib – Pancreatic/NSCLC cancer | Royalty Pharma | Synthetic royalty + secured loan | $250M upfront of $1.25B royalty; $750M loan (total $2.0B) | Phase 3 (pivotal trials) |

| BridgeBio Pharma (USA) | Acoramidis (Attramyloidosis) – cardiology | HCRx & Blue Owl Capital | Capped royalty monetization | $300M upfront (1.45× cap on repayments) | Commercial (launched 2025) |

| Nuvation Bio (USA) | Taletrectinib – ROS1 lung cancer | Sagard Healthcare Partners | Synthetic royalty + term loan | $150M on FDA approval; $100M loan facility (total $250M) | Phase 3 (NDA submitted) |

| Eagle Pharma (USA) | Bendeka – CLL/NHL oncology drug | Blue Owl Capital | Capped royalty sale | $69M upfront (1.3× cap) | Commercial (marketed since 2015) |

| Biogen (USA) | Litifilimab – Lupus antibody (autoimmune) | Royalty Pharma | R&D funding for royalty stake | $30M/quarter over 6 qtrs (up to $250M) | Phase 3 (two trials ongoing) |

| BioInvent Intl. (Sweden) | Mezagitamab – IgA nephropathy (autoimmune) | XOMA Corp. (royalty aggregator) | Royalty & milestone sale | $20M upfront; $10M on FDA approval (total $30M) | Phase 3 (pivotal trial) |

Table 1: Global royalty-based financing deals in H1 2025. These publicly announced transactions illustrate the breadth of participants – from small European biotechs to Big Pharma – and a variety of structures. “Upfront” indicates immediate capital received; many deals include contingent milestones or capped payout totals.

As shown above, at least nine notable royalty/structured finance deals were disclosed in the first six months of 2025, together raising over $3.4 billion for the developers. The deals ranged from as large as Revolution Medicines’ $2 billion funding arrangement to as modest as BioInvent’s $20–30 million royalty sale. While each transaction is unique, certain patterns emerge.

Most deals were tied to products in late-stage development or recently launched, as investors still demand some proof-of-concept. Therapeutically, oncology assets attracted the lion’s share of capital (thanks largely to the mega-deal for a RAS-inhibitor cancer drug), with rare diseases and immunology also well represented. We analyze these patterns below, followed by deeper dives into several representative case studies.

Who’s Doing the Deals: Therapeutic Area and Phase Distribution

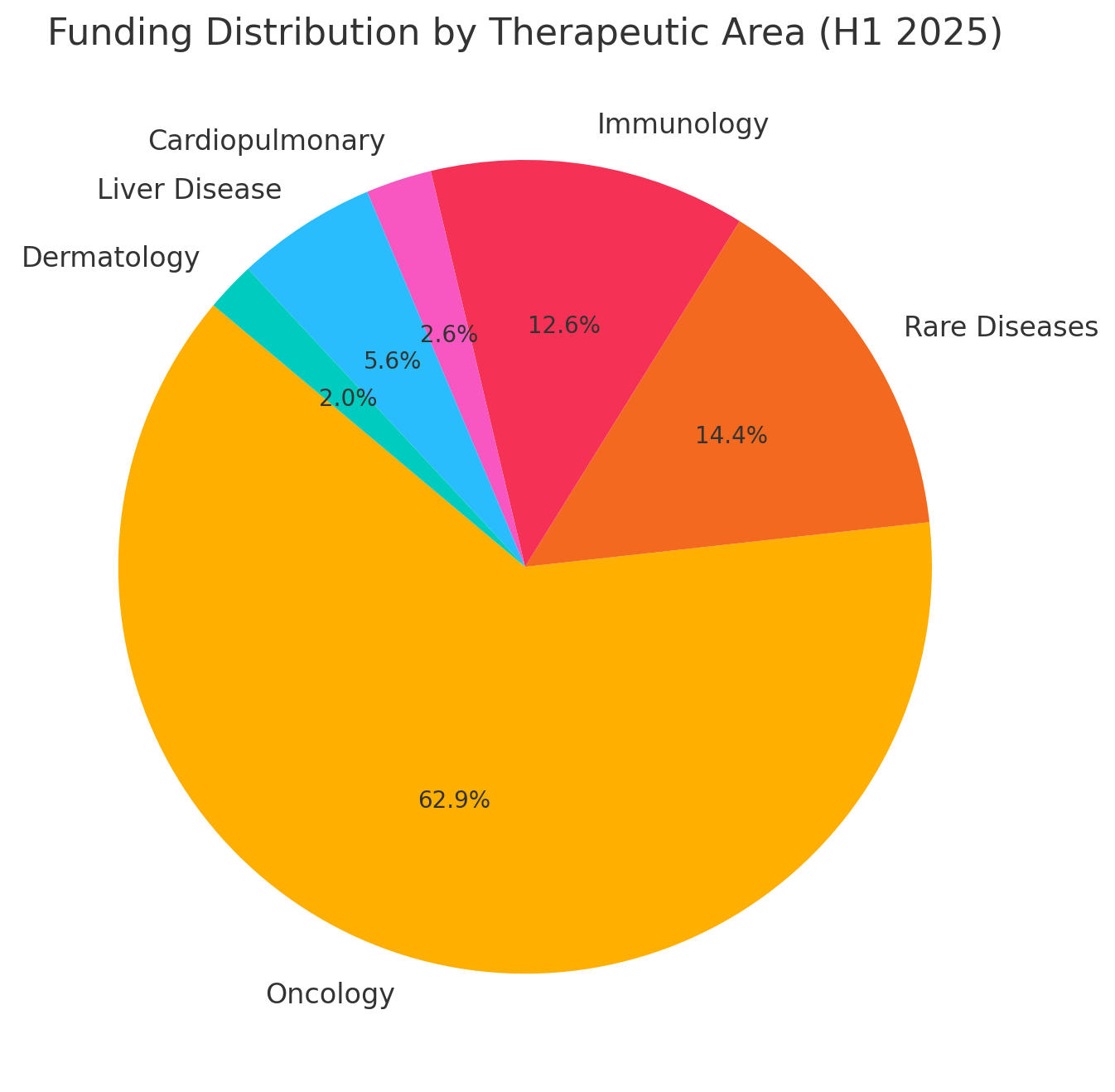

Therapeutic focus: The H1 2025 deals skewed toward the oncology space. By volume, approximately 70% of the total disclosed funding went into cancer-related assets – including a novel targeted therapy for pancreatic/lung tumors, a precision radiopharmaceutical diagnostic, and an established chemotherapy product.

This dominance is unsurprising: oncology assets often have large revenue potential and active interest from financiers. The next largest category was rare genetic diseases (~16% of volume), driven by a major deal for a cardiovascular rare disease drug and another involving gene therapies. Immunology/Inflammation deals comprised roughly 14% of the pie, including funding for an experimental lupus drug and monetizations of treatments for autoimmune liver and kidney diseases.

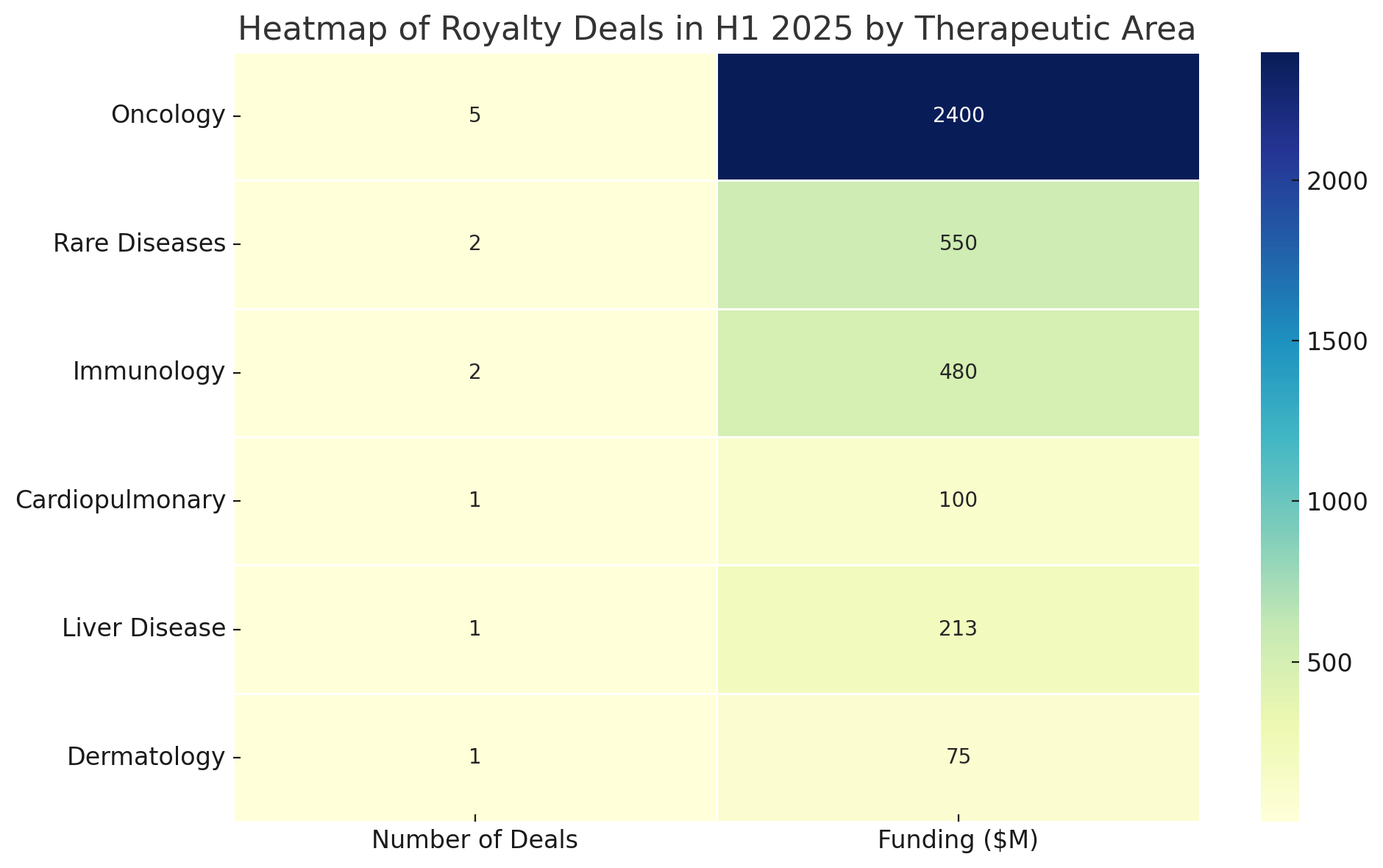

Heatmap of H1 2025 deals by therapeutic area and development stage. Darker cells indicate a higher count of deals in that category. Oncology assets accounted for the most deals overall, especially at the Phase 3 stage, while royalty financings for preclinical or Phase 1 programs were absent.

The prevalence of cancer and rare disease deals reflects where many biotech companies currently have valuable assets to monetize. Oncology in particular has seen intense investor competition for royalties, as any product with breakthrough potential (e.g. Revolution’s RAS inhibitor) can justify a hefty upfront payment in exchange for a slice of future blockbuster sales.

Meanwhile, therapies for ultra-rare or genetic diseases – though smaller in market size – are attractive for royalty investors when they come with approved status or well-validated Phase 3 data (as with BridgeBio’s ATTR-cardiomyopathy drug, approved in the U.S. as Attruby). In contrast, we saw no royalty financings for early discovery or preclinical programs in H1 2025. The risk at that stage remains too high for this model: investors generally waited until at least Phase 3 or product launch before advancing funds, unless the structure included rigorous downside protection.

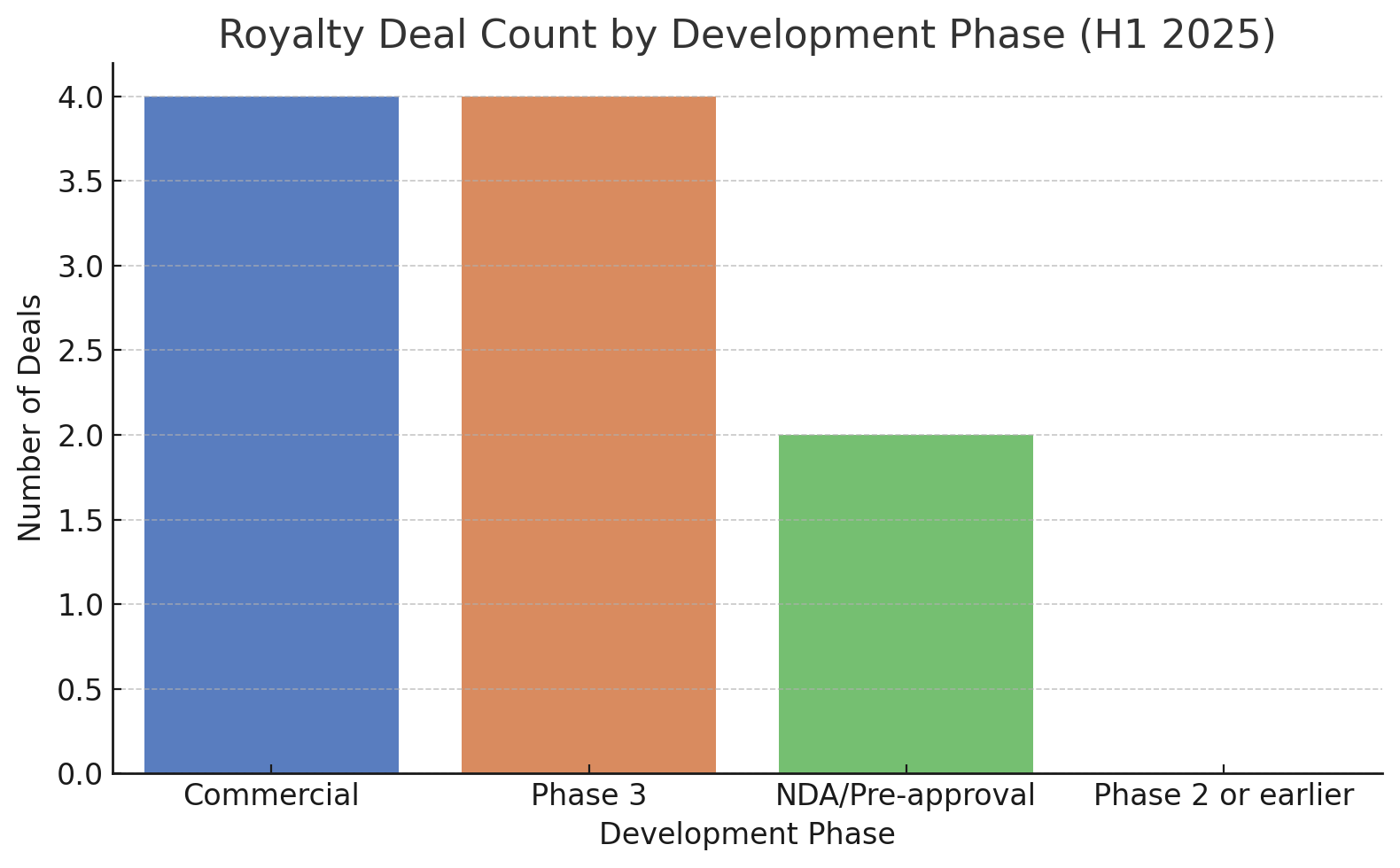

Indeed, if we categorize deals by the development phase of the asset at signing, nearly all were for Phase 3 or commercial-stage products. About half of the deals (e.g. Revolution, Nuvation, Biogen, BioInvent, Heidelberg) involved drug candidates in Phase 3 trials or awaiting regulatory approval. The other half targeted products that were already on the market or freshly approved (BridgeBio’s acoramidis, Eagle’s Bendeka, Genfit’s elafibranor).

None of the disclosed deals financed molecules in Phase 2 or earlier. This bias highlights that royalty financiers in 2025 were primarily interested in late-stage, de-risked assets – essentially stepping in to fund product launches or expand indications, rather than gamble on unproven science. Biopharma companies with early-stage science but no near-term revenue streams largely had to pursue other funding avenues (or structure deals around future milestones rather than sales-based royalties).

Another noteworthy pattern is the use of caps and time limits in these deals. Nearly every transaction in H1 2025 included terms to cap the total payments to the investor or limit the royalty’s duration. For instance, Eagle Pharmaceuticals’ $69 million deal gives Blue Owl Capital rights to Bendeka’s U.S. sales only until the investor has received 1.3× its money back, after which royalties revert to Eagle. BridgeBio’s $300 million financing was similarly capped at 1.45× the investment. Nuvation’s deal will cease once Sagard obtains between 1.6× to 2.0× its outlay (depending on how quickly sales ramp up).

These caps ensure that if the drugs are very successful, the biotech issuer eventually regains the full revenue stream – a way to avoid “selling the farm” entirely. Even uncapped arrangements often had term limits: Revolution Medicines’ synthetic royalty runs for 15 years on sales of its RAS inhibitor. In short, 2025’s deals were structured not as open-ended annuities but as structured financings with negotiated end-points or maximum payouts. This reflects a balancing of interests: biotechs are willing to share a portion of upside, but only up to a point, while investors secure a healthy return if the product succeeds without perpetual entitlement.

Trends Shaping Royalty Financings in 2025

Non-Dilutive Capital in a Risk-Off Market

Underpinning all these deals is the pursuit of non-dilutive financing during a period of market stress for biotech. For emerging biopharma companies, royalty monetization offers cash today without issuing new shares – a critical advantage when stock prices are depressed. “The market for life sciences equity financings has all but dried up… if you do raise equity it’s at very unattractive, highly dilutive prices,” observed one industry lawyer. This sentiment was echoed across boardrooms in 2025.

With the NASDAQ Biotech Index languishing and venture capital firmer in retreat, CEOs turned to their science as collateral – quite literally trading slices of future drug revenue to keep the lights on. Royalty deals allowed companies to extend their cash runways to 2027 or beyond (as Genfit and Heidelberg Pharma explicitly stated) without crushing their shareholders with a cheap equity raise.

From an investor’s perspective, these arrangements turned the usual risk/reward on its head: instead of equity upside, the investor’s return is tied to the drug’s commercial success. This alignment has appeal in volatile times. As Royalty Pharma’s CEO Pablo Legorreta put it regarding the Revolution Medicines partnership, the funding paradigm “enables [the biotech] to retain control… as well as capture significant value if the clinical development is successful,” while Royalty Pharma shares in that success .

Notably, such deals often emerge as alternatives to outright acquisitions or licensing. In Revolution’s case, analysts noted the $2B financing likely removed immediate takeover speculation – the company got enough cash to go it alone, obviating the need to sell at today’s prices. Likewise, smaller players like BridgeBio and Nuvation used royalty financings to avoid partnering away their crown-jewel assets. By doing so, they preserve long-term upside (should the drug become a hit) at the cost of giving investors a hefty preferred cut in the early years.

This dynamic – trading some future profits for certainty today – has drawn comparisons to mortgage financing or even the “house money” strategy in gambling. It’s a pragmatic response to the funding squeeze: biotech firms essentially monetize part of an asset’s value now to ensure they survive long enough to realize the rest of that value later. As one biotech CFO explained, the royalty deal “provides immediate, less-dilutive capital… while preserving significant upside for our shareholders”.

Investors like HCRx and Blue Owl, on the other hand, are effectively betting that these companies’ drugs will generate robust sales that pay back the investment plus a premium. Their upside is contractually limited (via caps or fixed royalty rates), but in exchange their downside is often mitigated – for example, if sales underperform or timelines slip, the royalty may extend until a cap is met, ensuring they eventually recoup principal plus yield. It’s structured risk-sharing at its core.

Regional Patterns: Western Dominance and Asian Prospects

Despite the global nature of biopharma, H1 2025’s royalty financings were largely a transatlantic affair. The majority of issuers were U.S.-based companies, followed by a few in Europe. The investor side was dominated by North American firms: specialists like Royalty Pharma and HealthCare Royalty (both headquartered in the U.S.), multi-strategy asset managers like Blue Owl (U.S.), and alternative lenders such as Sagard (Canadian).

European biotech participants (e.g. France’s Genfit, Germany’s Heidelberg Pharma, Sweden’s BioInvent) also turned to these mostly U.S. funding sources to tap global capital pools. One might have expected more Asian activity – given the rapid growth of biopharma in China and Korea – but Asian dealmakers played a more muted direct role in the H1 2025 royalty trend.

That is not to say Asia was absent: Asian markets provided some of the underlying assets and inspiration for these financings. Nuvation Bio’s cancer drug, for instance, taletrectinib, was originally developed by a Chinese biotech (and the royalty financing will fund its U.S. launch if approved). And Japanese companies have historically pioneered forms of revenue-sharing deals. But in these six months, we did not see any major China- or Korea-based funds announcing royalty purchases in Western firms, nor Asian biotechs publicly monetizing royalties at large scale.

It appears the royalty financing boom is still centered on the U.S. (the world’s largest drug market) and enabled by U.S. capital. One reason is structural: U.S. law and markets have a well-trodden path for royalty transactions, and firms like Royalty Pharma (with >60% global market share in biopharma royalty acquisitions) have deep U.S. roots.

However, industry observers anticipate a rise in Asian participation in coming periods. As Asian biopharmas mature, they too face the choice of selling some future sales for cash. Notably, China’s cash-hungry biotechs have begun exploring creative financings (in past years, companies like I-Mab and Innovent have sold rights or future revenue streams to investors).

Some Asian investment funds are also ramping up credit arms targeting healthcare. In 2025, for example, CBC Group (a Singapore-based fund) and others were rumored to scout for royalty deals, and a few years prior a consortium from China had partnered on a large U.S. royalty transaction. So while H1 2025 deals were Western-dominated, the geographic balance may shift if Asian capital markets embrace the model. For now, the pattern remains “Wall Street funds biotechs globally,” with U.S. firms providing the lion’s share of royalty financing to companies wherever they are.

Interestingly, even within Big Pharma, we saw an East-West contrast: American pharma giant Biogen embraced a royalty funding for its lupus drug, whereas no similar moves were reported from European pharmas in H1 2025. (European big pharmas tended to rely on internal cash or traditional alliances.) Biogen’s deal with Royalty Pharma – essentially offloading part of the risk of a Phase 3 lupus program – underscores how U.S. firms are often at the vanguard of financial innovation. In this case Biogen leveraged New York-based Royalty Pharma’s capital to underwrite a trial program, something that would have been unusual for a Pfizer or Novartis to do publicly.

The cultural comfort with externalizing risk via financial engineering appears stronger in the U.S. pharma ecosystem, whereas European and Asian pharma have been comparatively conservative (preferring joint ventures or straight licensing). That said, the success of these deals may prompt imitators globally, especially if credit remains tight. A senior partner at WilmerHale noted that more private credit funds have entered the space and are “expanding their portfolios” by creating novel transactions to meet the demand for capital. The entry of more players – be it Asian sovereign wealth funds or European pension investors – could further globalize the royalty financing trend in late 2025 and beyond.

Asset Maturity vs. Early-Stage Science

A critical trend in H1 2025 was the focus on assets at or near commercialization. Royalty financiers overwhelmingly favored drugs that had either recently launched or were in Phase 3 with clear late-stage data. This speaks to a fundamental constraint of the model: it works best when there is a definable future revenue stream to slice. Early-stage science, lacking predictable sales forecasts, is generally ill-suited to pure royalty deals. As our survey shows, 0% of the deals were for pre-Phase 2 assets. Even Phase 2 programs, which still carry substantial clinical risk, did not attract royalty monetization in this period. The sweet spot was products on the cusp of approval or newly marketed.

This has several implications. First, companies with earlier projects had to get creative – often by structuring deals around milestones or R&D funding rather than sales royalties. (For example, a pre-approval asset might secure funding in exchange for future milestone payments or a convertible debt element, rather than a straight percentage of sales.) Biogen’s litifilimab deal is essentially this: Royalty Pharma’s $250 million is tied to development milestones and will convert into mid-single-digit royalties only if the drug is approved.

It’s a hybrid structure bridging a gap until the asset matures. Likewise, Sagard’s financing for Nuvation Bio was contingent on FDA approval – no approval, no royalty payments; the investor’s initial risk is mitigated by that condition. These structures show how early-stage risk can be partially managed in royalty deals by back-loading investor returns to post-approval periods.

Second, the emphasis on late-stage assets meant that many deals in H1 2025 were essentially launch financing vehicles. BridgeBio explicitly stated that the $300 million royalty sale would “support the launch of Attruby and ongoing late-stage programs”. Nuvation said the Sagard funds would “fully fund U.S. commercialization of taletrectinib, if approved”. Even Revolution’s massive deal was framed as enabling an expansive Phase 3 program and anticipated market rollout with the company retaining control.

In effect, royalty financings became a substitute for what in better times might have been IPO proceeds or big-pharma partnerships to launch drugs. Rather than going public or selling rights country-by-country, these biotechs raised the needed capital via royalty investors and chose to launch products themselves (or at least keep global rights). It’s a notable shift: royalty funding as an alternative to partnering. The CEO of Revolution Medicines highlighted that contrast, calling the Royalty Pharma alliance a “new funding paradigm” that – unlike a traditional pharma partnership – allows them to keep full control of development and commercialization.

The downside of this focus on mature assets is that truly novel early-stage science might struggle to find funding. There is a concern of neglecting early innovation: if public markets and VCs are weak and royalty financiers only back near-market drugs, who will finance the next generation of discoveries in their infancy? It’s a valid question. However, one could argue that by sustaining later-stage programs, royalty deals free up other capital in the system for earlier stages. Also, some investors are adapting royalty models to earlier stages through “synthetic royalties” on future milestones or indications.

The trend of 2025 suggests that as long as the credit/equity environment remains challenging, most royalty dollars will chase the comparatively safer, late-stage bets. Early-stage biotechs may have to hunker down, progress their programs to proof-of-concept, and then leverage royalty financing as they approach pivotal trials or launch – essentially using royalties as a bridge over the “valley of death” between Phase 3 and revenue.

Capped Royalties and Synthetic Structures

Two buzzwords frequently mentioned in 2025’s deals were “capped royalties” and “synthetic royalties.” These refer to structural nuances that have now become standard in the industry.

A capped royalty means the investor’s right to revenue stops once they have received a predetermined return (often expressed as a multiple of the investment). This cap was a common feature in H1 2025 agreements. Why cap the royalty? From the biotech issuer’s perspective, it was critical for justifying the deal to stakeholders: a cap ensures the company isn’t permanently giving away a chunk of its bestseller’s sales. Instead, the royalty is more like a loan that gets paid off from sales over time. For example, BridgeBio’s royalty to HCRx/Blue Owl will terminate after they get 1.45 times the $300 million paid. If acoramidis (Attruby) becomes a multi-billion dollar franchise, BridgeBio will eventually keep all the upside beyond that cap – a win-win in their eyes.

Investors accept caps because it protects them on the downside (they structure it so the cap is likely achieved within a certain sales scenario), and if sales are stellar, they might hit their return quickly and free up capital for the next deal. It essentially converts an indefinite royalty into a structured payoff schedule tied to sales. Many caps also escalate over time – Nuvation’s deal, for instance, had a cap of 1.6× if paid by 2031, increasing to 2.0× if it drags out past 2034 – an incentive for the company to drive high sales early (so the obligation ends at a lower multiple). Capped royalties thus bring predictability: both sides can model the best and worst case. In 2025’s uncertain climate, this predictability was valued.

Synthetic royalty refers to a royalty interest that is created artificially, rather than coming from an existing license agreement. In traditional royalty monetization, a company might have licensed a drug to Big Pharma and is entitled to royalties – those existing royalties can be sold (as Genfit did with its Ipsen partnership on elafibranor, or BioInvent with its Takeda-partnered antibody). But many biotechs had not out-licensed their assets; they still owned 100% of the product rights. For them, the solution was to issue a new royalty interest on future sales of their own product (often in specific markets or up to a certain sales level) and sell that to investors.

This is a synthetic royalty financing. Revolution Medicines’ deal is a prime example: the company retains ownership of daraxonrasib, but is granting Royalty Pharma a contractual right to a share of future worldwide sales (tiered royalties on the first $2 billion, $4 billion, etc. of revenue for 15 years) in exchange for $1.25 billion now. No royalty existed before – it’s effectively a private royalty stream minted for this transaction. Synthetic royalties have the benefit of flexibility: they can be tailored in size, scope, and term.

They enabled companies like Revolution and Nuvation to raise large sums without licensing the product or giving up equity – a very attractive proposition. As one commentary noted, RIF (Revenue Interest Financing) structures like these blend elements of credit and royalties, offering companies more flexibility than a fixed loan and more cash upfront than a traditional license. The synthetic royalty is secured only by the product’s future revenues, not by the company’s assets, which can be seen as non-recourse financing in a sense (if the drug fails, in many cases the company doesn’t owe repayment beyond maybe a termination fee – the investor simply loses future royalty entitlement).

The proliferation of synthetic royalties in 2025 speaks to how biotechs have learned to monetize their potential revenue while keeping operational control. It’s essentially a way to have your cake and eat it: you get funding now but you don’t hand the keys of your program to a partner. Of course, the cost is that if the drug does well, you’ll be sharing the spoils for a number of years. Notably, synthetic royalty deals often came paired with debt or other instruments as part of a “structured package.”

For example, Revolution’s $2B arrangement was roughly half royalty, half debt – combining the advantages of both (royalty piece has no fixed interest or covenants, debt piece provides extra cash with the company’s assets as collateral). Sagard’s deal with Nuvation similarly combined a royalty (to be paid from sales) with a traditional term loan tranche. This mixing and matching of financing tools is a trend in itself: each deal is custom-built. In 2025 we rarely see a plain-vanilla sale of a perpetual royalty. Instead, deals resemble a collage of tranches, tiers, caps, and conditions – bespoke structures optimized for the needs of that company.

Why Biotechs Embraced Royalty Monetization in 2025

In the style of The Economist, one might ask: is royalty financing a sign of strength – ingenious financial engineering to fuel innovation – or a sign of desperation in a cash-starved industry? The answer lies somewhere in between, but leaning toward the former. Biotech has always been an industry of high risk and high reward, and 2025’s royalty deals show the sector’s adaptability in navigating the financial cycle. Several key reasons explain why so many firms, from tiny BioInvent to heavyweight Biogen, chose this path in H1 2025:

Avoiding equity dilution at low valuations

With biotech indices down sharply from their 2021 peaks, issuing new stock in 2025 often meant locking in a painfully low valuation of the company. Royalty deals provided an influx of capital without issuing shares, sparing existing shareholders from dilution. Genfit’s CEO, for example, explicitly pitched its €185M HCR deal as “non-dilutive” and crucial for extending cash runway to 2027. For management teams and boards, this is a compelling rationale – they’d rather pay a bit of revenue later than give away ownership now.

Maximizing value of pipeline while retaining control

Royalty financings enabled companies to self-fund their most promising assets instead of licensing them out early. In a traditional model, a small biotech might license its drug to Big Pharma for an upfront payment and milestones, losing a degree of control and upside. In 2025, several companies essentially said: why not act as our own “pharma partner” by bringing in a financial investor? This way they keep control of development and commercialization strategy. Revolution Medicines exemplified this; management touted the Royalty Pharma deal as letting them keep the steering wheel on a portfolio of RAS inhibitor drugs with blockbuster potential.

The CEO of Revolution called it a “groundbreaking partnership” that preserved optionality – code for maintaining independence. Biogen’s deal, too, can be seen as retaining control of litifilimab (rather than perhaps co-developing it with another pharma) while sharing the cost burden.

Bridging to key milestones in a tight credit environment

Many biotech executives in 2025 were laser-focused on reaching value-inflection milestones – an approval, a Phase 3 readout, a first revenue – without running out of cash. Royalty financings served as bridge capital to get there. They were often structured to extend the runway just enough. For instance, RegenXBio’s $150 million upfront from HCRx was said to extend its cash runway into early 2027, past multiple upcoming gene therapy readouts.

Nuvation Bio explicitly stated that the Sagard funding could carry the company to potential profitability with no additional raises needed. This is golden language for a biotech – essentially claiming it’s the last financing required. In a world where follow-on equity financings were hard to come by, making such a claim was strategic to stabilize investor confidence. The royalty deals gave them the credibility to say “we have the cash to see this through.”

Investor appetite and competitive terms

It must be noted that royalty monetization became popular in 2025 in part because investors were willing to offer large sums on increasingly company-friendly terms. The entry of more private credit funds and institutional investors created competition, which likely improved pricing for biotechs. While these deals are hardly cheap money (the implied cost of capital can be high), many were structured with biotechs’ interests in mind – e.g. the caps protecting upside, interest-only periods on loans, etc. If only one or two players were in the market, terms might be harsher.

But by 2025, a dozen or more active financiers (Royalty Pharma, HCRx, Oaktree, Blackstone Life Sciences, Blue Owl, Sagard, OMERS, XOMA, etc.) were circling opportunities. A partner at WilmerHale observed that a new group of lenders had learned how to do these transactions and “know the pros and cons,” so now companies “have the tool in the toolbox” and will continue to use it. In other words, royalty financing matured into a semi-standard option, and companies found they could solicit multiple bids and negotiate favorable structures. The availability of willing capital made saying “yes” to royalty deals easier.

Aligning with long-term investors vs. short-term markets

Some biotech CEOs preferred the quiet stability of dealing with a private royalty investor over the vagaries of public market sentiments. The public market in 2025 was punishing – one day up on rumor, next day down on macro fears. In contrast, royalty deals often involve a single sophisticated counterparty that shares the company’s interest in the drug’s success over years.

This alignment of incentives can be appealing. For example, HCRx’s CEO, Clarke Futch, often emphasizes that their investments “underscore commitment to supporting innovation” and belief in the product’s potential. Such rhetoric, while promotional, signals a partnership mentality. For a biotech developing a drug, having a deep-pocketed partner who is literally invested in the drug’s future sales (rather than a hedge fund looking for a quick flip on the stock) can be reassuring. It’s akin to having a long-term co-owner of the asset, but one that doesn’t interfere with operations the way a co-development partner might.

All these reasons paint royalty monetization in a largely positive light – a smart financing hack to weather tough times. However, a critical analysis must also note the risks and costs. Biotechs are effectively betting that the chunk of future revenue they give up is worth less than the immediate benefits of the cash they receive. If they bet wrong – say, the drug wildly succeeds and they’ve parted with a huge stream cheaply – there could be regret (or at least questions from shareholders down the line about whether they needed to do that deal).

For instance, if daraxonrasib becomes the next Gleevec and Revolution has given away a portion of sales for “only” $1.25B, later on that could look like a very expensive cost of capital. Additionally, these deals often come with complex encumbrances – dedicated accounts, security interests in the royalty, covenants to keep the project on track, etc. They add a layer of contractual obligation that companies must manage carefully. In extreme cases, if a company defaults on a structured royalty agreement (e.g. fails to perform certain development obligations), it could even lose rights. Such scenarios are rare, but the point is that royalty financing is not free money; it is secured by the asset and its future, with strings attached.

On balance, the critical view might argue that 2025’s wave of royalty deals reflects the weakness of the biotech funding environment – a symptom of companies forced into “selling the family silver” to survive. And indeed, many management teams would likely have preferred straight equity financing at reasonable prices if it were available. But in the grand scheme, these financings also highlight the innovative resilience of the biotech sector. Rather than halting programs and waiting for markets to recover, companies found a way to advance drugs to patients via creative dealmaking. As the old saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention. Royalty monetization wasn’t invented in 2025 – it’s been around for decades – but it truly came of age in this period as a mainstream financing strategy, evolved and adapted to meet the needs of an industry in flux.

Notable Deal Spotlights: Case Studies from H1 2025

To illustrate how these trends play out in practice, let’s examine a few case studies of H1 2025’s most noteworthy royalty and structured finance transactions. Each sheds light on different motivations and deal architectures:

Case Study 1: Revolution Medicines & Royalty Pharma – $2 Billion for a RAS Blockbuster?

The deal: In late June, California-based Revolution Medicines announced a landmark funding deal with Royalty Pharma, worth up to $2.0 billion in total. Royalty Pharma provided $250 million upfront and committed up to $1 billion more in a series of milestone-based tranches, all in exchange for a “synthetic royalty” on Revolution’s lead drug candidate, daraxonrasib, a targeted cancer therapy. Additionally, Royalty Pharma offered a separate $750 million secured credit facility. This combination of an immediate infusion, future contingent payments, and a loan made it one of the largest and most complex biotech financings in recent memory.

Structure and terms: The synthetic royalty is tiered on global net sales of daraxonrasib for a 15-year term. Essentially, as daraxonrasib progresses, Royalty Pharma will pay Revolution in phases – $250M upfront, another $250M upon positive Phase 3 data in a key trial, and further tranches tied to FDA approval and sales milestones. In return, Royalty Pharma will skim a single-digit percentage of the drug’s future sales (ranging roughly 2.4%–7.8%, depending on sales level) for up to 15 years.

The loan portion, meanwhile, gives Revolution flexibility to draw funds for other pipeline needs, repayable with interest like a standard debt. Notably, there is no hard cap disclosed on Royalty Pharma’s total royalty take – instead the royalty simply terminates after 15 years. This means if daraxonrasib is extremely successful, Royalty Pharma could earn many multiples of its investment (albeit bounded by time).

This deal is essentially replacing a traditional partnership. Normally, a small-mid biotech with a promising Phase 3 cancer drug might license it to a big pharmaceutical company in return for an upfront sum and royalties. Revolution chose a different path: partner with a financial entity that doesn’t commercialize drugs but funds you to do it yourself. The CEO of Revolution Medicines, Mark Goldsmith, highlighted that this financing lets them retain full control of development and global commercialization, unlike a conventional licensing deal. In his words, it “exemplifies a new funding paradigm” for highly innovative biotech.

The subtext is that Revolution believes it can create more long-term value by staying independent and launching daraxonrasib on its own, and Royalty Pharma’s cash enables that bold plan.

Rationale and market reaction: The rationale for Revolution was straightforward: $2 billion is a huge war chest – likely enough to fund not only daraxonrasib through approval and launch across multiple cancer indications, but also to advance several other RAS-targeted compounds in its pipeline. By securing this sum, Revolution essentially immunizes itself against the volatile capital market for the next few years. It won’t need to raise equity or worry about cash constraints in its pivotal trials.

This in turn strengthens its negotiating position should any suitors come knocking; the company is under no financial duress to accept a low takeover bid. Indeed, analysts noted that this deal signaled Revolution is “off the table” as an acquisition target for now, which caused its stock to drop 5% on the news – investors who had bet on a quick M&A exit were disappointed. However, fundamentally the deal was seen as positive for Revolution’s prospects as a standalone.

For Royalty Pharma, this was a chance to bet on a potential blockbuster in the making, with structured downside protection. Daraxonrasib targets the notorious RAS oncogene (implicated in pancreatic and lung cancers among others) – if effective, it could be the first drug to hit all major RAS mutations, a multi-billion dollar market opportunity. Royalty Pharma is effectively providing staged funding that values the program highly, but if the Phase 3 results or approvals don’t pan out, Royalty Pharma isn’t on the hook for the full $1.25B (only the upfront $250M is at risk initially). It only pays the later tranches upon success, making this a kind of success-based financing.

Of course, if daraxonrasib fails entirely, Royalty Pharma also has its $750M loan claim (secured debt would give them certain rights in a downside scenario, perhaps even royalty on another asset or priority in liquidation). In essence, they structured it so that they share in the upside of a big cancer drug but have layered their exposure – part equity-like (the upfront royalty stake) and part debt-like. Pablo Legorreta of Royalty Pharma called it a “groundbreaking partnership” and emphasized Royalty Pharma’s unique ability to deliver such large-scale capital to help a biotech reach its strategic goals. It underscores Royalty Pharma’s role as the go-to financier for mega-deals of this sort, leveraging its ~$30 billion balance sheet.

Implications: This deal sent ripples through the industry. It suggested that even very large sums – usually only available via IPOs or pharma partnerships – could now be raised via royalty financing if the asset was compelling enough. It likely raised the bar (and expectations) for other late-stage biotechs: rather than sell out or dilute heavily, why not consider a royalty investor for a creative solution? It also demonstrated how flexible these structures can be (mixing royalties and loans, tiered milestones, etc.).

However, Revolution’s case is somewhat exceptional in scale and risk appetite. Not every company has a Phase 3 asset that could plausibly generate multi-billion sales. Royalty Pharma’s confidence here is notable – it’s willing to stake $1+ billion on a single pipeline product’s success (something it historically did mainly for approved drugs or very de-risked indications). That speaks to how much competition there is to finance high-quality programs: better Royalty Pharma funds it than let a rival capture that opportunity.

In sum, the Revolution–Royalty Pharma alliance in H1 2025 embodied the maximalist end of the royalty financing trend: huge dollars, complex structure, and a signal that alternative finance can rival pharma deals in magnitude. It provided a template that others will either emulate or be wary of, depending on daraxonrasib’s fate.

Should the drug succeed and Revolution go on to thrive independently, this will be hailed as a masterstroke of financing. If it fails, one might look back and question if such a large sum was wisely deployed. For now, it stands as a bold bet by both parties on the premise that new funding models can propel biotech innovation without Big Pharma ownership.

Case Study 2: BridgeBio & Blue Owl/HealthCare Royalty – Capped Cash for a Cardio Launch

The deal: In June 2025, BridgeBio Pharma, a Silicon Valley-based biotech, secured $300 million upfront through a royalty monetization agreement with a syndicate of two investment firms: HealthCare Royalty (HCRx) and Blue Owl Capital. The deal allows BridgeBio to monetize a portion of future royalties from its drug acoramidis (brand name Attruby in the U.S., BEYONTTRA in Europe), a treatment for transthyretin amyloidosis cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM). In return for the $300 million injection, the investors will receive 60% of BridgeBio’s European royalties on BEYONTTRA sales, but only up to a certain point – there is an initial cap set at 1.45× the invested amount.

Context: Acoramidis had recently achieved regulatory approvals (FDA approved it in December 2024 as Attruby, and the European Commission followed in early 2025 as BEYONTTRA). BridgeBio was preparing to launch the drug in a competitive market (ATTR-CM is the same indication targeted by Pfizer’s blockbuster tafamidis). While BridgeBio did partner with Bayer for European commercialization, it still was entitled to significant royalties from those sales (in the “low-30%” range, per BridgeBio). Rather than wait years for those royalties to trickle in, BridgeBio opted to pull forward some of that value via this deal. The $300 million provides cash to fund not only the U.S. launch and commercialization efforts for Attruby, but also to fuel BridgeBio’s pipeline of other genetic disease programs – all without issuing new stock or incurring traditional debt.

Deal terms and structure: Under the agreement, HCRx and Blue Owl receive 60% of the European net sales royalties that BridgeBio was otherwise owed. This applies to the first $500 million of annual sales in Europe. The structure includes an “initial cap” of 1.45×: meaning once the investors have received $435 million (which is 1.45 times $300M) in aggregate payments, their right to the BEYONTTRA royalty terminates. Based on sales projections, this cap could be reached in a certain number of years if the drug sells very well, or might never be reached if sales underperform – but in any event, BridgeBio won’t pay beyond that multiple. Additionally, the royalty is limited to the European market and a sales tranche (up to $500M/year), leaving BridgeBio’s U.S. and other region revenues untouched by the deal.

This setup essentially gave BridgeBio an upfront sum in exchange for a slice of European revenue until the investors get a 45% return on their money (plus their principal). By all accounts, that implies the investors expect a healthy uptake of BEYONTTRA in Europe – if it takes too long to reach the cap, their annualized return would diminish. The careful “1.45x” number indicates a negotiated balance: investors might have started wanting, say, 1.6–1.7×, and BridgeBio bargained them down to preserve more upside. The presence of two investors (HCRx and Blue Owl) suggests the deal was syndicated, possibly because $300M was a big bite for one fund or because each brought something to the table (HCRx with deep pharma royalty expertise, Blue Owl with large pools of capital looking for yield). It’s also notable that Blue Owl – a major name in alternative asset management – participated. This signals how mainstream such deals have become, attracting interest beyond the usual biotech-specialist financiers.

Implications for BridgeBio: From BridgeBio’s perspective, this was a strategic move to bolster its balance sheet at a pivotal moment. The company had a number of late-stage and newly approved products (Attruby being the flagship). Rather than run a traditional secondary stock offering (which might have been challenging after a recent run-up in share price, or simply dilutive), they chose the royalty route. The company’s SVP of Finance, Chinmay Shukla, emphasized that the transaction “strengthen[s] our balance sheet… while preserving significant upside for shareholders, with careful structuring that limits annual as well as total payments to the royalty investors”.

In effect, BridgeBio messaged this as “smart money” that doesn’t mortgage the whole future. By limiting both the rate (only 60% of one region’s royalties) and the total payout (1.45× cap), BridgeBio assured investors that it was not selling off its long-term fortune, just monetizing part of it. The cash extends BridgeBio’s runway and funds development of other programs (the company has a broad portfolio in genetic diseases and oncology), which hopefully will drive the next wave of value.

One can view BridgeBio’s deal as a classic case of a launch-stage biotech using royalty financing to go it alone. Many companies launching their first product either struggle to find the cash to scale up commercial operations or end up having to partner the product due to resource constraints. BridgeBio did partner in EU (with Bayer), but kept U.S. rights. The $300M will certainly help in building out U.S. sales efforts for Attruby, an expensive undertaking (cardiology specialists, patient identification efforts, etc.). It’s effectively non-dilutive launch capital. Considering that the alternative might have been a $300M equity raise (potentially diluting 15–20% of the company at prevailing prices), one can see why the royalty deal was attractive.

Investor’s angle: For HealthCare Royalty and Blue Owl, this investment offered a relatively lower-risk revenue stream from an approved drug for a serious disease. Acoramidis/Attruby had shown strong Phase 3 data (including a 42% reduction in cardiovascular events vs placebo over 30 months) and was entering a market pioneered by Pfizer’s drug tafamidis, indicating a validated commercial opportunity. By investing post-approval, HCRx/Blue Owl avoid clinical risk; their main risk is commercial adoption and competition. The 1.45× cap suggests they are targeting perhaps a mid-teens percent annual return – decent for a yield-oriented investment in a pharma asset.

Blue Owl’s involvement is interesting: known for technology and real estate investments, Blue Owl by 2025 had also built a Life Sciences lending arm. They likely saw the BridgeBio royalty as akin to a fixed-income instrument with an attractive return, backed by a product with projected blockbuster potential. Gibson Dunn, legal advisor to the investors, noted the deal as an example of providing “flexible capital solutions that help advance life-saving therapies”. In plain terms, it means investors frame these deals as win-win: the company accelerates a therapy to patients, and the investors earn a good return if patients indeed benefit (since that drives sales).

Capped royalty in action: BridgeBio’s case really highlights the benefit of the cap for the company. Suppose BEYONTTRA in Europe becomes a huge seller, with sales exceeding $500M annually for multiple years. Without a cap, BridgeBio might have to continue paying 60% of those royalties indefinitely, which could sum to far more than $435M. With the cap, once the investors have recouped $435M, BridgeBio will get back 100% of its European royalty stream. Essentially, BridgeBio would have turned $435M of future royalties into $300M of immediate cash – equivalent to a discount rate that is the investors’ return. If sales are robust, that cap might be hit in just 3-4 years, freeing the royalty thereafter. If sales are slower, the cap might take longer or might not be reached by the time the royalty agreement’s term ends (caps often have backstop dates too, though details weren’t public). Either way, BridgeBio ensured that beyond a point, the full long-term value reverts to the company.

In an interview, BridgeBio’s CEO Neil Kumar quipped that this financing was “as close to non-dilutive as it gets,” allowing them to keep focus on developing “first-in-class and best-in-class genetic medicines” (paraphrased from typical BridgeBio messaging). Analysts generally viewed the transaction positively, seeing it as removing near-term financing risk. The stock market reacted calmly; BridgeBio’s stock was up ~5% on the news, indicating investor approval of the move to secure funds without equity (the slight rise perhaps reflecting relief that a rumored equity offering was off the table).

Overall, BridgeBio’s royalty monetization exemplified how biotechs with approved products can leverage future royalties to fuel both the product’s launch and broader pipeline ambitions. It’s a story of a company threading the needle: getting needed cash while keeping future upside largely intact. Should Attruby/BEYONTTRA become a standard therapy in ATTR-CM, BridgeBio will eventually enjoy the full royalty flow once the investors are paid off, essentially having gotten $300M at a reasonable “interest” cost. If the drug disappoints, the company still keeps the $300M (with no obligation to pay it back other than from whatever royalties materialize), which could be life-saving capital for its other programs. Thus, management effectively hedged their bets, ensuring they have funds to diversify into other pipeline projects regardless of one product’s trajectory.

Case Study 3: Biogen & Royalty Pharma – Big Pharma Dips Its Toes

The deal: In February 2025, Biogen Inc., one of the world’s leading biotech-pharma companies, announced an agreement with Royalty Pharma to secure up to $250 million in funding for Biogen’s Phase 3 lupus nephritis drug litifilimab . This deal was notable because it involved a large-cap pharma utilizing royalty financing – a tool more commonly used by cash-strapped smaller firms.

Under the agreement, Royalty Pharma would provide Biogen with $50 million or so per quarter over about six quarters (totalling $250M), and in exchange Royalty Pharma would receive mid-single-digit royalties on litifilimab’s sales if the drug is approved, as well as unspecified success-based milestone payments.

Structure: Essentially, Royalty Pharma’s payments function as R&D funding to offset the costs of litifilimab’s Phase 3 trials. Biogen is running multiple large studies of litifilimab in systemic and cutaneous lupus – costly endeavors. The $250M from Royalty Pharma de-risks Biogen’s investment. In return, Royalty Pharma’s right to royalties kicks in upon regulatory and sales success: specifically, Royalty Pharma will get a percentage of future sales (reported as mid-single-digit, likely ~5%) and possibly some one-time payments if certain approvals are achieved.

If litifilimab fails in trials or is not approved, Biogen presumably keeps the $250M without further obligation (this detail wasn’t explicitly stated, but typically these R&D funding deals are non-recourse if the product fails; Royalty Pharma just loses its bet). In other words, Royalty Pharma is sharing the development risk: it pays upfront for trials, and will earn a return only if the drug reaches market and generates revenue.

Biogen’s rationale: Why would Biogen – a profitable $40+ billion company – need to do this? Several reasons stand out:

Risk mitigation

Litifilimab, while promising (it’s a monoclonal antibody targeting BDCA2 for lupus), is still high-risk. Lupus is a notoriously difficult disease area, with many past trial failures industry-wide. By getting an external funder to cover $250M of the trial costs, Biogen effectively hedged part of the risk. If the trials fail, Biogen has saved itself a quarter-billion in sunk cost (Royalty Pharma’s money covered it). If the trials succeed, Biogen will gladly pay a royalty because it means they have a valuable new drug on the market. As one analyst put it, “the deal offers a way to share the risk of an experimental medicine while preserving cash for other pipeline projects”. For a company facing multiple pipeline bets, offloading risk on one of them can be a prudent portfolio management strategy.

Budget and optics

Biogen in early 2025 was under pressure to rejuvenate growth as its core franchises (multiple sclerosis drugs) were declining. It had just given somewhat soft financial guidance for the year, causing shares to slip. By bringing in $250M external funding, Biogen signaled fiscal discipline – it can invest in R&D without blowing up its expense line or reducing earnings guidance further. It’s essentially non-dilutive, non-debt capital to fund R&D, improving optics on the income statement (the Royalty Pharma funds might be recognized as deferred revenue or some funding liability, but they don’t count as debt and they aren’t equity). It might have been easier to justify internally and to investors than ramping up R&D spend by a quarter billion with no offset.

Focus on core programs

Biogen’s CEO had been vocal about focusing on Biogen’s core neurologic and rare disease pipeline and being careful with spending after some setbacks. Litifilimab, while potentially significant, is outside Biogen’s traditional CNS focus (lupus is immunology). By financing it externally, Biogen in a sense compartmentalized this program. If it succeeds, great – Biogen pays a royalty. If it fails, Biogen hasn’t diverted too much of its own capital from other priorities like Alzheimer’s, ALS, etc. It’s a way to pursue an opportunity without overcommitting resources that could be used elsewhere.

For Royalty Pharma, this deal expanded its model of funding not just small biotechs but large pharma’s clinical programs. It shows that even cash-rich pharma will take “free money” if structured attractively. Royalty Pharma likely saw litifilimab as a high-upside gamble: lupus therapies can be blockbusters (if effective, given the limited options for severe lupus). By putting in $250M now, Royalty Pharma could earn royalties for the life of the drug (patents likely into the 2030s) – a long tail of revenue if litifilimab becomes standard of care.

The mid-single digit rate is modest, but on possibly multi-billion sales that could yield a nice return. Moreover, Royalty Pharma negotiated milestone payments too, which could accelerate payback. For example, upon FDA approval Royalty Pharma might get a lump sum from Biogen – effectively a success fee. So it’s somewhat structured like an advance plus milestone and royalty. According to Reuters, this Biogen lupus investment was one of Royalty Pharma’s highlight deals of recent times, mentioned alongside the Geron deal. It demonstrates Royalty Pharma’s strategy to go beyond just buying existing royalties and proactively finance R&D for a cut of future sales (a trend also seen with its deals with small companies like Cytokinetics in 2022, etc.). Royalty Pharma has remarked that it is “increasingly investing in research-stage medications” and not just marketed drugs. The Biogen deal perfectly encapsulates that shift.

Reception: The investment community largely viewed the Biogen-Royalty deal as a smart, if conservative, move for Biogen. It signaled that Biogen is willing to innovate financially and not just scientifically. Some saw it as Biogen lacking confidence to invest its own money fully – but more charitably, it’s Biogen being prudent. After all, why not leverage someone else’s capital if it’s available on reasonable terms? It also perhaps set a precedent: might other big pharmas follow suit for their riskier projects? It’s not unheard of (e.g., in the past Pfizer did a similar funding deal for its Phase 3 PCSK9 inhibitor bococizumab in 2016 with Royalty Pharma), but it’s still relatively rare.

If 2025’s lean times continue, we might expect more established companies to externalize R&D risk this way, essentially outsourcing some development costs to investment firms that specialize in drug risk. It blurs the line between traditional pharma and biotech financing: normally pharma funds R&D internally or via partnerships, but here they are tapping the capital markets (through an intermediary) directly tied to a product’s outcome.

For Biogen, if litifilimab succeeds – Phase 3 data are expected in 2026–2027 – they will owe perhaps 5% of sales for years to Royalty Pharma. Should the drug be, say, a $2 billion/year seller, Biogen would pay $100 million/year to Royalty Pharma. Over a decade that could be $1 billion – a hefty sum compared to the $250M received. But Biogen will not mind if that scenario comes true; it means the drug is a major success fueling growth (and Biogen would be getting the other 95% of sales). If the drug fails, Biogen essentially got $250M to soften the blow (and Royalty Pharma eats the loss). Biogen’s calculus is clear: given the binary risk, it’s worth giving up a sliver of upside to insure part of the downside. Or in finance terms, Biogen purchased an insurance policy on its R&D – and Royalty Pharma was the insurer.

This partnership also underlines the increased collaboration between big pharma and financial investors. It’s an interesting dynamic when a large pharma is willing to let an outsider share in a molecule’s economics. It suggests a more open mindset that not every program must be fully owned if sharing it can reduce risk and speed development. We may see more such deals as pipelines get broader and companies seek to optimize capital allocation. In the long run, if litifilimab becomes a new standard in lupus, patients and doctors won’t care that 5% of sales go to a finance firm – but the model that helped bring the drug to market will have quietly done its job. It’s finance greasing the wheels of pharma innovation.

Case Study 4: Genfit & HealthCare Royalty – Rescuing a Balance Sheet

The deal: Not all royalty financings are about funding shiny new programs; some are about repairing balance sheets and ensuring survival. A pertinent example is Genfit, a French biotech, which in January 2025 announced a royalty financing agreement with HealthCare Royalty (HCRx) for up to €185 million (approx $200M). Genfit is a late-stage company focused on liver diseases. The deal was centered on Genfit’s drug elafibranor (brand Iqirvo), which had recently been approved in the U.S. and EU for a rare liver condition called PBC (primary biliary cholangitis).

Genfit had licensed elafibranor to Ipsen back in 2021, so Genfit was entitled to royalties from Ipsen’s sales of Iqirvo. Under the January 2025 deal, Genfit sold a portion of those future royalties to HCRx in exchange for an upfront €130M and up to €55M more in milestones.

Crucially, this transaction was paired with Genfit addressing an overhang on its books: Genfit had outstanding convertible bonds (OCEANE notes due October 2025) that were looming. Part of the royalty deal was contingent on Genfit using proceeds to buy back and retire those convertibles, effectively cleaning up its debt and avoiding dilution (since OCEANE converts could otherwise turn into equity if not repaid). The royalty financing thus served a dual purpose: give Genfit growth capital and fix its capital structure by eliminating debt that could have led to bankruptcy or major dilution in 2025.

In CEO Pascal Prigent’s words, it was a “pivotal step” to strengthen Genfit’s financial outlook and “eliminate [the] convertible debt overhang,” positioning Genfit on strong footing to execute its R&D plans.

Structure: The Genfit-HCR deal is an example of a capped, structured royalty on a single product. HCRx provided €130M upfront. Genfit can get an additional €30M and €25M from HCRx upon Iqirvo hitting certain sales milestones in the near term, making the total up to €185M. In return, HCRx will receive a portion of the royalties Ipsen pays Genfit on Iqirvo sales – but only up to an agreed cap, after which all future royalties revert to Genfit.

The exact cap wasn’t publicly quantified, but it effectively limits how much HCRx can earn (likely some multiple of the €185M). Also, the royalty is “limited recourse”: HCRx’s repayment comes solely from Iqirvo royalties, and Genfit retained rights to all the milestone payments from Ipsen and any royalties beyond the cap.

The deal required buy-in from Genfit’s bondholders to waive certain covenants and allow the royalty collateral – Genfit convened a meeting and bondholders gave unanimous approval, seeing that getting cashed out was better than risking conversion in an undercapitalized company (genfit press release). Once approved, Genfit concurrently repurchased essentially all the OCEANE notes. By doing so, Genfit removed €85M of debt from its balance sheet (approx the principal outstanding) using part of HCRx’s funds, and will use the remaining funds to invest in its pipeline (particularly a promising program in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure).

Implications for Genfit: This was truly a lifeline deal. Genfit had been through ups and downs – a prior failure in NASH nearly sank the company in 2020, but pivot to PBC succeeded with regulatory approvals. However, commercializing a rare disease drug and servicing a looming debt would have been a tall order for a small company. The royalty financing solved that: Genfit now has a cash runway beyond 2027 (by its own estimate) and no debt deadlines in the near term. It gave Genfit breathing room to focus on science rather than survival. The stock market greeted the news positively; Genfit’s shares jumped on the announcement, reflecting investor relief that bankruptcy or massive dilution had been averted.

For HCRx, this deal was in their sweet spot: HCR specializes in commercial or near-commercial products in need of non-dilutive capital. Iqirvo (elafibranor) for PBC, while for a small indication, has a clear market in an orphan disease and was just launched – a point where many companies seek to monetize royalties. HCRx can earn a steady royalty until the cap, likely over several years as Ipsen sells Iqirvo globally. HCR’s CEO Clarke Futch noted they “firmly believe in the strong potential Iqirvo delivers to patients” and framed the investment as supporting an innovative company. It’s a standard rhetoric: HCRx provides the cash, Genfit delivers the science, patients benefit, everyone wins.

This case study underscores how royalty financing can be a tool for financial restructuring. It’s not just for funding new trials; it can recapitalize a company. Genfit used future royalties (which are an asset) to pay off debt (a liability) – effectively converting one form of obligation into another with more flexible, success-dependent terms. It’s reminiscent of project financing in other industries: use the project’s future cash flows to finance its development and pay debts. Here, the “project” is a drug.

From a critical perspective, one could ask: did Genfit give up too much of its future Iqirvo royalties for short-term relief? Possibly, if Iqirvo’s sales boom beyond expectations, Genfit will have given away a chunk of that upside for cheap. But given Genfit’s size and the urgency of the bond maturity, it was a pragmatic trade-off. The alternative might have been a distress equity raise or risking default on the bond in late 2025. By taking HCRx’s money, Genfit lived to fight another day – continuing its pipeline work in ACLF and other liver diseases – and if Iqirvo does amazingly well, Genfit still gets all royalties after HCRx hits its cap. So again, it’s about survival and extending runway at the cost of some capped upside.

Genfit’s move also highlights something about the 2025 environment: traditional refinancing options were limited. In a better market, Genfit might have issued new equity to pay off the convertibles, or restructured the debt via a new bond. But investors weren’t lining up for that, whereas a specialized firm like HCRx was ready to transact on the asset’s strength. It shows royalty financiers sometimes function as “white knights” for companies at risk, providing a kind of rescue capital when others won’t. This has a parallel in other sectors where alternative lenders step in if banks or public markets pull back.

In conclusion, Genfit’s H1 2025 royalty deal with HCRx was a textbook example of using royalty monetization for corporate turnaround. It may not have grabbed headlines like the billion-dollar biotech deals, but for Genfit and its stakeholders, it was arguably even more consequential. It ensured the company’s viability and wiped away a debt cloud, illustrating the versatility of royalty financing as a financial strategy: not only fueling growth, but also cleaning up past financial baggage – all anchored by the anticipated success of a therapy reaching patients.

Conclusion: The “PE-ization” of Pharma Finance?

By mid-2025, it was clear that royalty and revenue-based financings had cemented themselves as a third pillar of biopharma funding alongside equity and traditional debt. Some commentators dubbed this trend the “PE-ization” of pharma, likening it to how private equity and private credit have reshaped other industries (e.g., the rise of private deals in pharma akin to leveraged buyouts or structured credit deals) – a term even used in trade press as Bluebird Bio’s royalty deals were part of a “PE-ization of pharma” trend (as referenced in a BioSpace opinion headline). What it really signifies is a maturation of the biotech financing ecosystem: companies now have a broader menu of financing tools to choose from, and they are exercising that choice to optimize outcomes.

Total deal volume in just the first six months of 2025 – over $3.4 billion disclosed – is striking. For comparison, royalty financings in all of 2022 globally were estimated around $6–7 billion (an already high mark). 2025 is on pace to smash records, reflecting both the robust demand for capital in biotech and the willing supply of funds from investors seeking exposure to pharma innovation without buying equity. The deals spanned therapeutic areas (oncology leading, but rare diseases and immunology prominent), geographies (though US-centric in finance, the assets and companies were global), and company sizes (from microcaps to Big Biotech).

One can argue this trend is cyclical – when equity markets eventually rebound, perhaps companies will flock back to cheaper equity and fewer will sell royalties. Indeed, if biotech stock prices surge and capital becomes abundant, royalty deals might become less necessary (why give up product revenue if you can sell stock at high prices or borrow cheaply?). Some industry veterans have questioned whether this royalty rush is sustainable if conditions normalize.

But others point out that something has fundamentally changed: an entire class of specialized investors now exists and has money to put to work. They won’t just disappear in a bull market; they’ll adapt by maybe financing riskier assets or offering even better terms to compete with equity. As WilmerHale’s Shuster noted, “once you have the tool in the toolbox, you’re going to continue to use it” – both companies and investors have built expertise and infrastructure around these deals, suggesting a lasting role.

Moreover, the very nature of biotech has evolved – with so many single-asset and first-time commercial companies emerging, the need for bespoke financing solutions is permanent. In past decades, promising drugs in Phase 3 would almost invariably end up acquired by big pharma or partnered. Now, many biotechs aim to launch on their own (out of ambition or necessity), which creates a financing gap that royalty deals neatly fill. This points to a structural shift in how medicines are developed and brought to market, with investment firms playing a bigger part in the drug development value chain rather than just public shareholders or pharma partners.

From a macro perspective, the royalty financing boom of H1 2025 can be seen as a sign of the times: an innovative industry meeting a challenging environment with equal innovation in financing. It has allowed critical drugs – from cancer therapies to rare disease treatments – to progress toward patients despite economic headwinds. It has also given investors alternative avenues to participate in healthcare’s fortunes aside from volatile equities. In classic Economist style, one could wryly note that where there’s a will (and future cash flows), there’s a way (to monetize them).

There are cautionary notes to strike as well. Royalty financings transfer risk in complex ways, and if not carefully managed, a company might find itself over-leveraged on future revenues, which could hamper flexibility or even deter potential acquirers (a pharma buyer might balk if a target’s crown jewel product is encumbered by a rich royalty obligation). It introduces a new class of stakeholders whose interests need to be balanced in a company’s strategic decisions. And while it can stave off dilution, it doesn’t eliminate underlying business risk – ultimately, products must succeed for these financings to pay off. If a spate of high-profile royalty-funded programs fail clinically, one can imagine investors becoming more gun-shy or demanding even higher returns, which could make the model less appealing.

For now, though, the first half of 2025 will be remembered as a watershed moment when royalty finance went from a niche tactic to a mainstream feature of biopharma finance. As the data and examples in this report have shown, royalty deals provided billions in capital that kept the innovation engine humming when other fuel sources ran low. In the process, they have begun to subtly reshape the industry’s landscape – empowering biotechs to stay independent longer, infusing private capital into drug development in new ways, and forging partnerships that don’t fit the traditional mold of pharma alliances but achieve similar ends.

Whether this is a lasting equilibrium or a temporary expedient, only time (and the stock market) will tell. But one thing is certain: the toolbox has gotten bigger for biotech CFOs. And as long as scientific breakthroughs continue outpacing the availability of easy money, those new tools – royalties, revenue interests, and the like – will remain in active use, funding the next wave of biopharma innovation one deal at a time

Member discussion