Vintages and Valuations: Why Timing Is Everything in Biotech VC

In venture capital, your returns depend less on genius and more on calendar luck. Especially in biotech.

Venture capitalists like to imagine they make money through insight. The right founders. The right sectors. The right syndicates. But behind the curtain of strategy decks and IRR models lies a far simpler truth: the year you wrote the cheque matters more than almost anything else. This truth is codified in the language of vintages.

What Is a Venture Vintage?

A venture vintage refers to the year a fund starts investing its capital—usually the year of its first deployed deal. Just like in winemaking, vintages in VC are a way to group returns, measure environmental factors (macro conditions, IPO windows, rate regimes), and compare performance with some degree of fairness.

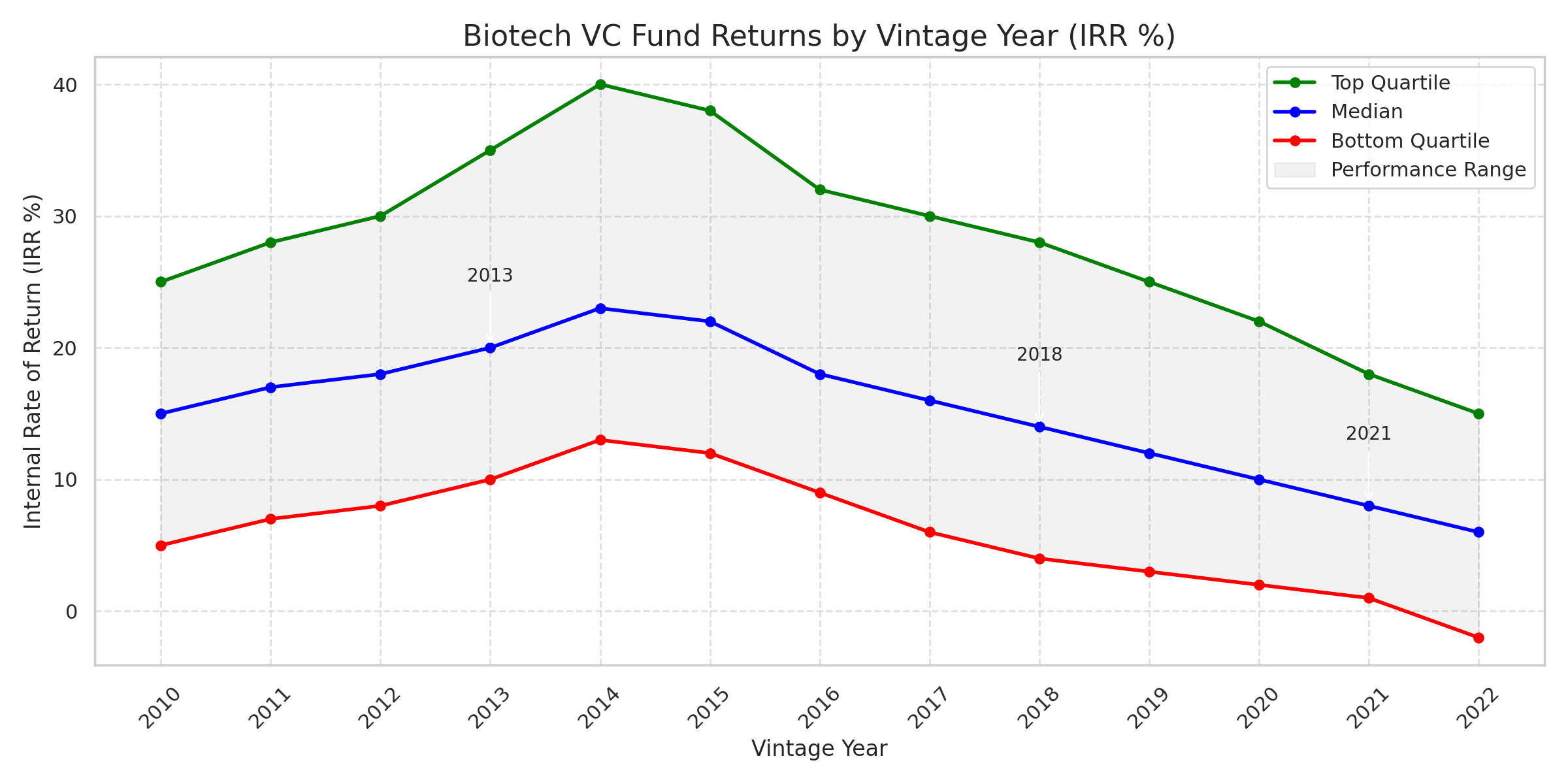

Why does it matter? Because your vintage year locks you into a market environment that affects everything: valuations, exit velocity, capital availability, and the patience of LPs. Two funds with equal talent—one launched in 2013, one in 2021—will have radically different outcomes. One got a rising tide of IPOs and low interest rates; the other inherited a frozen exit window, multiple compression, and a crowded cap table.

The Biotech Angle: Timeframes Are Longer, Luck Matters More

Biotech is especially sensitive to vintage timing. Unlike SaaS or marketplaces, there is no revenue pivot in drug development. A Series A in therapeutics is often followed by 6–8 years of clinical grind, regulatory bureaucracy, and binary risk events.

This means that a 2010 vintage fund could exit into a golden era of biotech IPOs around 2017–18. A 2018 fund, however, would see its maturing portfolio stumble directly into the 2022 market crash. That’s not bad management. That’s vintage risk.

Visualising the Vintage Effect

Let’s make this concrete.

Here’s what the chart tells us:

- The gap between winners and losers is huge. In some years, the spread from top to bottom quartile exceeds 30 percentage points.

- 2013 was a golden vintage. It entered a period of easy money, low inflation, and a buoyant M&A market. Median returns sat comfortably above 20%.

- 2021 was a cautionary tale. Funds invested at peak valuations. Just a year later, IPO markets shut, capital dried up, and many assets became unfinanceable. Even the best managers struggled to find exits.

- 2018 looked good on paper… until it wasn’t. Clinical assets matured just as the 2022 crash hit, leading to dilution, down rounds, and stagnating exits.

2024 and 2025: A Vintage Reset

This brings us to now. If 2021 was the party and 2022–23 the hangover, then 2024 and 2025 are the years of sober realignment.

Capital is tighter. Valuations are lower. Exit markets remain cautious. And yet—this is precisely why these may be the best vintages of the decade.

Smart money is returning selectively. M&A is trickling back. The IPO freeze is beginning to thaw. Most importantly, the competition has thinned. Many tourist investors from 2021 have left the building. What remains is durable capital, hard-won conviction, and founders who’ve survived a cycle.

Funds deploying in 2024–25 will enter at compressed valuations, face little pricing pressure, and have time to build for the next up-cycle. Whether this turns out to be the 2010 of the 2020s, or just a slower version of 2001, will depend on discipline—and luck.

Can You Buy a Specific Vintage?

You can’t log onto your broker and “buy the 2013 biotech vintage.” But you can do something close:

- Secondaries: Buying fund interests from LPs who want early liquidity.

- Continuation vehicles: Rolling over maturing assets from older vintages into new, longer-term vehicles.

- Fund-of-funds: Diversifying across vintages by allocating to multiple managers and years.

Institutional LPs now treat vintage diversification as a core risk-management tool. It's no longer enough to pick the best GP—you need to spread your bets across years to survive market cycles.

What GPs Can Do About It

General Partners can’t control their vintage—but they can adjust how they navigate it. Here’s what sophisticated funds are doing:

- Deploy capital barbell-style: Slow down in overheated years, accelerate during corrections.

- Reserve follow-on capital: Don’t frontload Series A and B checks if exit markets are closed.

- Structure opportunistically: SPVs, secondaries, and royalty financings can add liquidity even in bad vintages.

- Prepare exits early: In biotech, timelines are long. Exits require planning, not spontaneity.

LPs: Stop Falling for Vintage-Agnostic IRRs

When an LP says, “this fund was top quartile,” always ask: Which year? A 25% IRR from 2010 means one thing. The same IRR from 2021 is Herculean.

The best LPs spread commitments across vintages, compare like-for-like, and discount top-line IRRs if they were harvested in a bubble. One fund, one year, is not a strategy.

Founders: Why You Should Care

Founders often ignore vintage dynamics, assuming all capital is equal. It’s not.

A fund that started investing in 2019 is nearing its end. They want exits. Fast. A fund from 2024 is playing the long game. They can afford to wait, reinvest, and guide you through a full cycle.

If you’re choosing between term sheets, ask: When did this fund start investing? You may learn more than from the cap table alone.

Final Word: The Calendar Doesn’t Lie

Biotech is slow. Capital markets are not. When the two align, returns follow. When they don’t, even the best molecule can sit on ice.

So if you're launching a fund, joining a syndicate, or simply raising your Series A, remember: you are not just betting on science—you are betting on time.

Because in venture, as in winemaking, the vintage tells you everything.

Member discussion